Summary

- Biblical queen: Queen of Sheba

- Mythological queen: Helen of Troy

- Born out of an egg: Clytemnestra

- Revenge in the family: Electra

- Mythological murder: Hecuba

- Cassandra’s curse

- Widowed Queen of Carthage: Dido

- Queen of the Amazons: Hippolyta

- Queen Consort of Thebes: Jocasta

- True drama: Antigone

- A warrior queen: Zenobia

- Fearless queen: Tomyris

- A mythological demoness: Lamia

This article was co-written by Ian Munday.

Juicy Legends

We can certainly find juicy, hair-raising, tales of women in power in the antique world. But where are the paintings celebrating these classical queens? And here is the conundrum – although these Queens led legendary lives, their legends seem to sail through art history with barely a reference to them on canvas.

Queen of Sheba

One exception to the trend of missing Queens was the Queen of Sheba – one of the few Queens who appears in the Bible. But this fine lady, compared to her contemporaries, was fairly anodyne. Legend has it that she arrived in Jerusalem with a caravan full of bling, presenting her gifts to King Solomon and testing his legendary wisdom with some tough questions and conundrums. Oh, and she also had hairy legs about which Solomon reprimanded her. This is 2000 years before hair removal creams and seems a bit rude when she has just gifted him a huge pile of gold and spices.

Jacopo Tintoretto painted her, as did Piero della Francesca and Claude Lorrain. Sheba was also celebrated by Lorenzo Ghiberti in a relief sculpture. But she is an exception. Most visual images in the art of the ancient Queens were not picked up by painters until the Victorian Pre-Raphaelites. And nothing can be further from the veneer of Victorian respectability than these marvelous women.

Queens from Classical History: Jacopo Tintoretto, The Queen of Sheba and Salomon, 1555, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Helen of Troy

The Trojan War offers us rich regal pickings. Helen of Troy is probably known to us all in some form. The ultimate female beauty—often celebrated on film—she was known as “the face that launched a thousand ships.” She has been depicted in art since the 7th century BCE. Abduction and seduction are always in fashion, and by the time of the Pre-Raphaelites, painters could not, it seems, keep their brushes off her.

Above Evelyn De Morgan represents Helen in a pretty, pink gown gazing into her own reflection. Isn’t this how we think of Helen of Troy—a ravishing beauty to who things happened rather than a conjurer of disasters herself? Without agency of her own, Helen was a plaything of the gods as it was Aphrodite who gave her as a reward to Paris, the son of King Priam. Even though she, Helen, was Queen of Sparta and already married to Menelaus. Helen’s sister was called Clytemnestra. She was rather more active in the downfall of men and cities than her sister. She was married to Menelaus’s brother, the king of Mycenae, who had only become involved in the Trojan War to protect his brother’s honor. Both these sisters usurped their husband’s power but in different ways: Clytemnestra’s rebellion was triggered most horribly, when Agamemnon sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia, to the gods in order to get fair winds to sail his fleet of ships to Troy.

Queens from Classical History: Evelyn De Morgan, Helen of Troy, 1898, De Morgan Collection, Barnsley, UK.

Clytemnestra

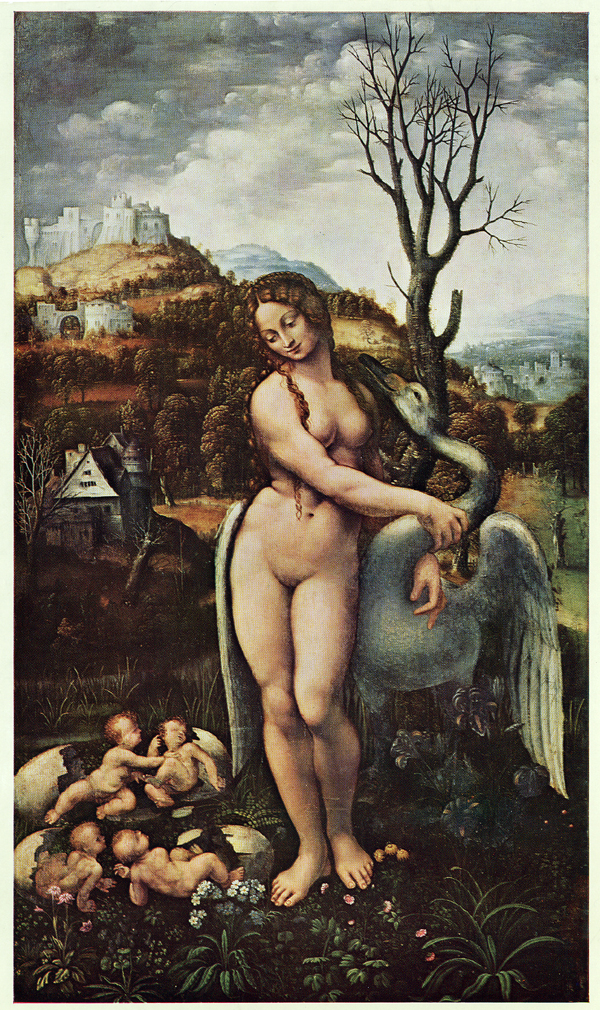

The two sisters, Helen and Clytemnestra had very interesting origins. Their Father was Zeus who disguised himself as a swan in order to seduce their mother Leda.

Queens from Classical History: Follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Leda and the Swan, early 16th century, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Being fathered by a swan, they were born out of an egg (no we are not making this up). Above we see a Renaissance image of the two sisters, born out of one egg, and out of the other egg, their brothers Castor and Pollux. Not bad for a culture that knew nothing of genetics.

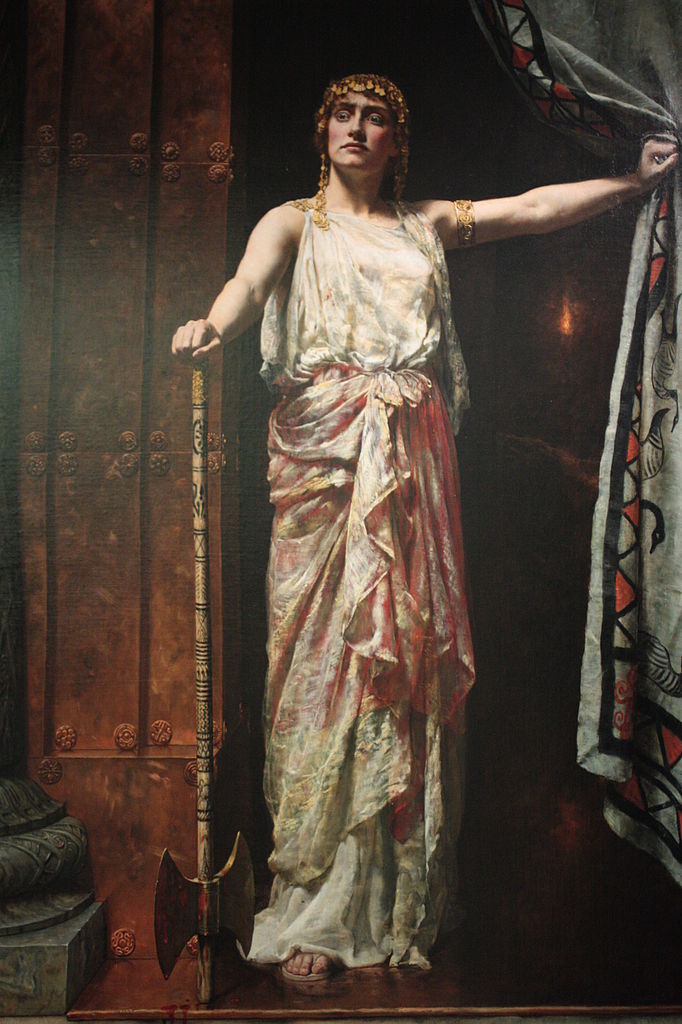

Clytemnestra was quite rightly enraged by Iphigenia’s death, and planning revenge, she took a lover whilst her husband was away at Troy. When Agamemnon returned, the two of them, the Queen and her lover, murdered him in his bath.

John Collier, Clytemnestra, 1882. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Electra

Electra was the daughter of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon. She in her turn became obsessed with revenge against her mother for the murder of her father. When Electra’s brother Orestes returned from exile and murdered their mother and her lover, Electra then danced herself to death in a frenzy. She is wonderfully represented in music, most notably by Mozart in his opera Idomeneo. And by Richard Strauss in the opera Electra. Yet inexplicably this highly dramatic creature seemed to hold little appeal to visual artists.

For committing patricide, Orestes was pursued by the Furies (who gave us the highly useful noun and adjective ‘fury’). However, though this whole marvelous tale might have enriched our language and literature, it certainly didn’t give us a lot of fine art. Justice violently meted out to men must be another of those subjects the rich weren’t especially fond of hanging on their walls.

Queens from Classical History: William Adolphe Bouguereau, Orestes Pursued by the Furies, 1862, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, USA.

Hecuba

Still focussed on Troy, Hecuba is another fascinating character: Queen of Troy, wife to Priam, mother to Hector, Cassandra, and Achilles (and some 15 other children besides). After Troy’s fall, Hecuba is enslaved by Odysseus, but when her youngest son is murdered by King Polymestor, she goes mad and blinds the murdering king and then murders his two sons. In another version, the gods turn her into a mad dog. But the legend of Hecuba has to wait until the late Baroque period before it is committed to canvas by Giuseppe Maria Crespi.

Queens from Classical History: Guiseppi Maria Crespi, Hecuba Kills Polymestor, 18th century, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium.

Cassandra

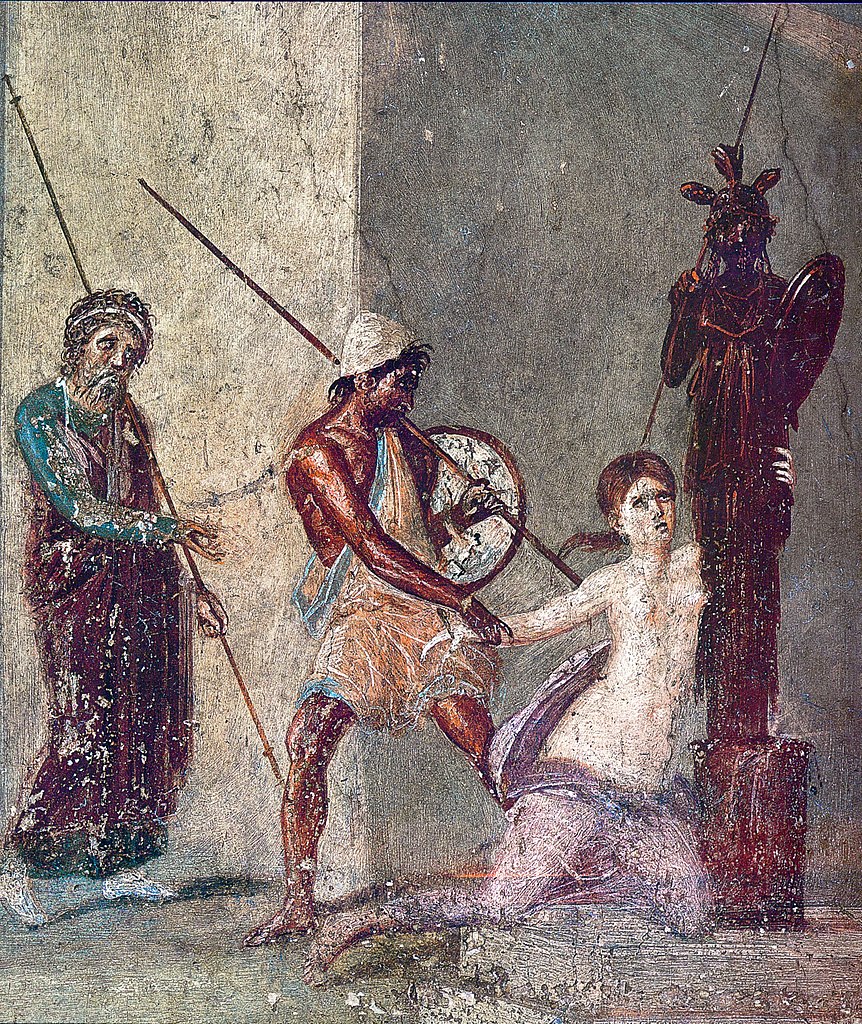

Cassandra is the daughter of Hecuba and Priam, Troy’s version of the Princess Royal. Prophetess, and prone to hallucinations, not to mention bouts of hysteria, she foresees the outcome of Paris’s abduction of Helen and warns that Troy will fall in battle. But, labeled a hysterical female, she is not listened to. She hides in the temple for safety, clinging to a statue of Athena. But she is found and raped by a warrior called Ajax the Lesser. Sadly Cassandra’s astonishing gift of prophecy, and her despair at never being believed, seem of less interest to artists than the scene of brutal rape, which has been recorded repeatedly since early times. Below we see the mural of Cassandra found in the Casa del Menandro, Pompeii.

Queens from Classical History: Cassandra clings to the Xoanon while Ajax the Lesser is about to drag her away in front of her father Priam (standing on the left), Roman fresco from the atrium of the Casa del Menandro, Pompeii, Italy. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Dido

As a postscript to the end of the Trojan War, we have Dido, Queen of Carthage. She is a little better served by art history. Dido was the widowed Queen of Carthage. Aeneas, son of a Trojan prince and the goddess Aphrodite, escapes the sacking of Troy and is on his way across the Mediterranean to form the city of Rome at the Olympian God’s behest. Aeneas sails into Carthage and Dido falls for him hook, line, and sinker. They have a torrid affair but when he leaves to follow his destiny she completely falls to pieces and makes a funeral pyre of his belongings and throws herself onto it. This story is marvelously portrayed in operas by Purcell and Berlioz, referenced in plays by Shakespeare, and even finds its way into modern gaming in Civilisation. The story of a boy who meets a girl – a boy has a mission he can’t deviate from, and the girl dies heartbroken is clearly a winner.

Queens from Classical History: Dido and Aeneas, 10 BCE–45 CE, House of Citharist, Pompei, National Archaeological Museum of Naples. Wikimedia Commons.

Queens from Classical History: Joseph Stallaert, Death of Dido, 1872, Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium.

Hippolyta

Moving away from Troy we have Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons. Daughter of the Olympian god Ares, she crops up in classical literature appearing in works by Euripides, Homer, and many others. She also appears in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream, though little is made of her classical origins there. She had a famed golden girdle given to her by Ares, the capture of which becomes the last labor of Heracles.

Queens from Classical History: Nicolaes Knüpfer, Hercules Obtaining the Girdle of Hyppolita, 17th century, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia.

Jocasta

Still, in Ancient Greece we come to Jocasta. She was Queen Consort of Thebes. Firstly she was married to King Laius. However, the oracle predicted his murder by his own son (a punishment by the gods on Laius for abducting and raping a young boy). When Jocasta gave birth to a son (Oedipus) the baby was taken from her and given to a shepherd to leave on a mountain to die. That of course didn’t happen, so some sixteen years later Laius and Oedipus meet as strangers on the road and, in a fight, Oedipus kills Laius and then carries on to Thebes where he marries Queen Jocasta. Four children later, Thebes is in the grip of the plague and, through that same oracle, Oedipus is revealed to be the cause. When Jocasta realizes the truth, that she has married her son, she hangs herself in horror. When Oedipus discovers her body, he cuts her down, takes the comb from her hair, and with it blinds himself. Hugely dramatic stuff. But, though served well by the ancient writer Sophocles and the composer Stravinsky, she is quite overlooked in classical art history.

Queens from Classical History: Harold Speed, Lillah McCarthy as Jocasta in Oedipus Rex, 1913, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

Antigone

But the drama does not end there. Jocasta’s two sons fight and kill each other, Creon (Jocasta’s brother) takes the throne and decrees that one prince shall have proper funeral rites but the other shall remain unburied. Sacrilege in any religion, Jocasta’s daughter, Antigone, defies the king, and buries her brother, choosing divine law over civil law. Creon orders Antigone to be buried alive in a tomb. He then has a change of heart (so unlike a politician) and tries to release her but finds that, like her mother, she has hanged herself. Creon’s son Haemon, who was in love with Antigone, commits suicide by knife. Then, his mother Queen Euridyce also kills herself in despair over her son’s death. This was a family I feel was badly in need of some relationship therapy. But, this incredible tale is not represented by the old masters!

Queens from Classical History: Nikiforos Lytras, Antigone in front of the dead Polynices, 1865, National Gallery of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Zenobia

Queen Zenobia was the Queen of ancient Palmyra. A great warrior Queen, she successfully led her army to crush several Roman Provinces being defeated and subjugated by Emperor Aurelian. Her end is unclear. But, what we do know is that she was taken to be humiliated in Rome, where she probably starved herself to death. Do we see this majestic woman in art? No, we do not!

Queens from Classical History: Herbert Gustave Schmalz, Zenobia’s last look on Palmyra, 1888, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia.

Tomyris

Tomyris was the Queen of a Persian tribe, the Massagetae, and, like any good queen, was not scared of going to war. According to the writer Herodotus, Tomyris twice lead her people into battle against Cyrus, King of the new Persian Empire. Only after killing Tomyris’s beloved son was Tomyris slain. Out of revenge, Tomyris had Cyrus’s corpse beheaded and crucified, she then had his head shoved into a wineskin filled with human blood. The legend continues that Tomyris kept Cyrus’s head and used it as a drinking vessel. Now, this blood-curdling Queen did attract the attention of a couple of big names: Rubens and Mattia Preti.

Queens from Classical History: Peter Paul Rubens, Head of Cyrus brought to Queen Tomyris, 1623, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

Lamia

And finally, we have Queen Lamia. Very beautiful, desired, and seduced by Zeus. But Hera (aka Mrs. Zeus) is furious and forces Lamia to eat the children she had mothered with Zeus. From then on she becomes a phantom and a demon, seduces handsome young men and then devours their flesh. In a narrative poem by Keats, she is a half-serpent.

Queens from Classical History: Isobel Lilian Gloag, The Kiss of the Enchantress, 1890, inspired by Keats’s poem Lamia. Flickr.

Salome

Compare any of these ancient queens to women like the Empress Maud, Mary Tudor, or Catherine de Medici and they make those later queens look like a bunch of pussy cats. This begs the question as to why is it that all these fantastic Queens were so rarely represented in Renaissance and Baroque art when their lives were so extreme and dramatic that they literally beg to be portrayed.

Perhaps we see a clue in the paintings of Salome. This seductive femme fatale is depicted in classical art by the greats such as Titian, Solario and Cranach. This is a woman the Church can despise and blame with relish. She is neither royal nor powerful. She asks for the head of John the Baptist as a gift for dancing, at the request of her mother, but she is no real threat. In fact, in art, she is often bland in expression, almost demure.

Queens from Classical History: Mariano Salvador Maella, Salome with the head of the Baptist, 1761, Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, Madrid, Spain.

Sanitized or Shamed

Is this lack of powerful women on canvas connected to the patrimony of the Catholic Church? Did the Church demand that powerful and aggressive women, if depicted at all, had to be sanitized, shamed or simply ignored? Were these great queens of classical times, who were of course mostly pagans, just too risqué and anarchic in relation to the church’s values, to be seen in any form whatsoever?

Queens from Classical History: Titian, Judith with the head of Holofernes, 1515, Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome, Italy.

Marginalized Women

The Catholic Church, and society as a whole, has historically marginalized women. Their roles seem limited to slaves, servants, nuns, or wives. Not a lot of power there, and all in service to a priest, a Pope or a husband. Did it take the Enlightenment and modernistic thinking to allow us to appreciate these dramatic ladies? Perhaps their power was just too threatening for the paternalistic church and secular male leaders to admit they ever existed, so few commissions were made with them as subjects.

Powerful women triumphing over men is something art seems to have struggled with. I suspect Renaissance and Baroque painters were just too in thrall to the mother church and its money to stray into any feminist form of paganism. Ironically, Venus and Cupid crop up frequently as does Artemis or her Roman equivalent Diana. But these do not hold the complicated, violent and unashamed power of a Clytemnestra or a Jocasta. The omission of these legendary women on canvas remains something of an ongoing mystery and conundrum. What are your thoughts?

Author’s bio:

Ian Munday – since his retirement to Wales, Ian has been studying art history and creative writing. He gives guided garden tours at Powis Castle in Welshpool and also assists at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in Machynlleth.

Here you can read Ian’s article about the Sistine Chapel and Michelangelo.