Summary

- Read about the history of one of Italy’s most important landmarks: the Duomo of Siena. Its construction took several lifetimes and involved many venerated names in art history.

History of the Construction

As with many consequential places of worship throughout this region of Europe, the Duomo of Siena was consecrated on the site of a Roman temple. Led initially by Giovanni Pisano and thereafter by Francesco Talenti, the construction of the Duomo began in 1226 and continued for about 175 years! Siena’s highest point was chosen for the cathedral and it was built from back to front so that mass could be held during the long construction period.

View of Duomo in Siena, Italy in 2013. Photograph by Raimond Spekking via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Façade of the Duomo

The Duomo of Siena is covered in alternating strips of green, red, and white marble inlay that cover both the building and campanile. The façade is heavily ornamented with Venetian mosaics, bas-reliefs, and statuary. It features three doorways with a large rose window in the center. The construction of the façade was completed in two stages. The façade was decorated with abundant sculptures carved by Giovanni Pisano, including saints, beasts, and gargoyles. While the original sculptures were moved to the Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo around 1869, they were replaced by skillful copies that maintain Duomo’s tremendous artistic impact.

The Duomo Interior

Unlike the rather stark interior of the Duomo in Florence, the interior of the Sienese one is breathtaking! There is almost no vista inside where the eye doesn’t meet bas-relief panels, carved woodworks, frescos, or statuary. The walls and columns are covered in alternating black and white marble, inspired by the colors of Siena’s civic coat of arms. The columns support a captivating ceiling painted in rich blue with gold stars that continue under a dome. This dome predates Brunelleschi’s famous dome in Florence. The nave is separated from the two aisles by semicircular arches.

Starting at the apse above the rounded arches of the nave are 172 busts starting with the bust of Jesus Christ and Saint Peter, until Pope Lucius III. These are depicted clockwise around the interior of the Duomo. A gilded lantern at the top creates the mesmerizing effect of the sun beaming down.

The floor of the interior is a collection of masterpieces that took about six centuries to complete. It includes 56 etched and inlaid marble panels depicting many themes; mainly biblical and mythological stories. The oldest designs from around the 14th century are located closer to the entrance and are rectangular in shape, while the newer ones in the transept are dated to around the 18th century and are generally hexagonal or rhombuses.

Pisano Pulpit

One of the crowning jewels of Duomo is Nicola Pisano’s famous pulpit. Completed in 1268, the pulpit was a 13-year-long undertaking completed by Pisano and his esteemed assistants including Arnolfo di Cambio, Lapo di Ricevuto, and Pisano’s son Giovanni Pisano.

Nicola Pisano, Pulpit, Duomo, Siena, Italy, August 2021. Photograph by the author.

The pulpit is in a recognizable octagonal shape that was inspired by ancient Roman sarcophagi and is intricate in keeping with the Gothic style of Siena’s Duomo. There are seven Carrara marble panels that depict various scenes from the life of Jesus in intricate high-relief panels. These panels are held by nine columns made of granite, porphyry, and green marble.

Nicola Pisano, Pulpit, Duomo, Siena, Italy, April 2022. Photograph by Kate Wojtczak.

The outer columns are alternately placed on the base and on four stone lions. Above these outer columns are the personifications of the Virtues. There is also a solitary column in the center that is placed on a large pedestal decorated with representations of Grammar, Dialectic, Rhetoric, Philosophy, Arithmetic, Music, and Astronomy, i.e. the Seven Liberal Arts and Philosophers.

Nicola Pisano, Pulpit, Duomo, Siena, Italy, November 2007. Photograph by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.0).

This pulpit showcases Pisano’s remarkable talent for integrating classical themes into Christian traditions. It is a fine example of the classical revival of the Italian Renaissance and arguably Pisano’s most important work.

Nicola Pisano, Pulpit, Duomo, Siena, Italy, April 2022. Photograph by Kate Wojtczak.

Piccolómini Library

Located off the left aisle, the Piccolómini Library was conceived by Cardinal Francesco Todeschini-Piccolómini and was intended to house a priceless collection of illuminated 15th-century musical manuscripts.

The entrance to the Piccolómini Library is an intricately carved marble entryway created by Lorenzo di Mariano. The walls and ceilings within are adorned with brightly colored frescos painted between 1502 and 1508 by Pinturicchio and his pupils, including the illustrious Raphael. The frescos on the walls provide a historical chronicle of the life of Francesco Todeschini’s uncle, Enea Silvio Piccolomini derived from his autobiography, Commentarii.

Piccolomini Library, Duomo, Siena, Italy, April 2022. Photograph by Kate Wojtczak.

Enea Silvio Piccolomini (later Pope Pius II) elevated his sister’s son to the rank of cardinal and permitted him to assume the Piccolómini name. The frescos on the ceiling depict the Piccolómini coat of arms as well as mythological figures. Each of the panels is separately demarcated with ornamental designs and patterns, as well as painted frames that render the illusion of depth. The frescos are incredibly detailed, complete with elaborate costumes, architecture as well as landscapes. These are both imagined and recognizable, as required to present the narrative.

In 1503, the younger Piccolómini also ascended to the throne of Peter as Pope Pius III. Tragically, Pope Pius III died only 26 days into his papacy.

Piccolomini Library, Duomo, Siena, Italy, April 2022. Photograph by Kate Wojtczak.

Piccolómini Altar

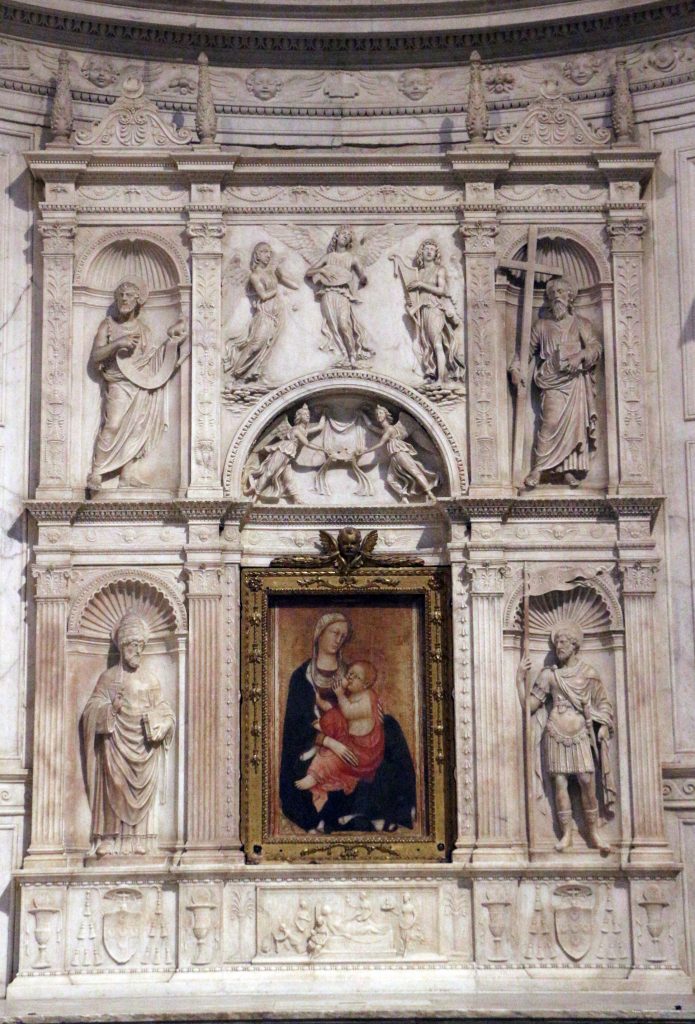

Located at the entrance of the Piccolómini Library, Cardinal Francesco Todeschini-Piccolómini commissioned sculptor, Andrea Bregno to create the Piccolómini altar intended to be his final resting place.

Bregno’s design was inspired by his altarpiece in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. The construction began in 1481, however by 1486 Bregno was in ill health and returned to Rome while his workshop remained to continue the work. The central focal point of the Piccolómini altar is Paolo di Giovanni Fei’s painting known as the Madonna of Humility (ca. 1390). The Carrara marble façade is covered in high relief with ornamental patterns, motifs, cornices, and a coat of arms. There are various ornamented niches framing the painting to hold statuary.

Piccolómini Altar, Duomo, Siena, Italy. Photograph by Gaspa via Flicker/Wikimedia Commons.

Florentine sculptor, Pietro Torrigiano created the Saint Francis sculpture that is placed in the upper left niche, but Torrigiano abandoned the project soon after. In 1501, another budding Florentine sculptor, Michelangelo Buonarroti was commissioned to complete the altar. However, it was around the time that Michelangelo also received the commission for the colossal David and the Sienese project took a backseat.

Andrea Bregno, Piccolómini Altar, Duomo, Siena, Italy, October 2015. Photograph by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

After Todeschini-Piccolómini’s brief reign as Pope Pius III, his heirs convinced Michelangelo to complete the statues in 1504 and a new contract was drawn. The four statutes in the lower niches were completed with the help of assistants and represent the Saints Peter, Augustine, Gregory, and Paul. It is believed that the Saint Paul sculpture was a self-portrait of Michelangelo. Despite the repeated requests of the Piccolomini family, the other envisioned statues were not completed and Michelangelo’s contract was annulled in 1530 by the descendent of Pope Pius III, Archbishop Francesco Bandini Piccolomini. Towards the end of the 18th century, a Madonna and Child sculpture, believed to be the work of either Jacopo della Quercia or Giovanni di Cecco, was added to the central niche where it remains today.

The altarpiece was never completed, however, since Cardinal Todeschini ascended to the papacy, he was buried in the Vatican.

Michelangelo, Saint Paul, ca. 1501-1504, Piccolómini Altar, Duomo, Siena, Italy. Web Gallery of Art.

Cappella di San Giovanni Battista

Cappella di San Giovanni Battista or the Chapel of John the Baptist is located on the left arm of the transept. It is adorned by a striking doorway that was created in the early 16th century by Lorenzo di Mariano. The walls are partially decorated by frescos that depict scenes from the life of John the Baptist and portraits by Pinturicchio. Frescos are separated by heavily ornamented patterns that are highlighted in gold to create a breathtaking effect. A small carved Baptismal Font is set on a marble inlaid floor in the center of the Chapel.

View of Cappella di San Giovanni Battista, Duomo, Siena, Italy, August 2021. Photograph by the author.

Among the many treasures of the chapel stands out a striking bronze sculpture of John the Baptist by Donatello. Donatello’s rendition of John the Baptist depicts him as a beggar dressed in rags. He is malnourished and grimacing in agony as he occupies an intricately carved niche. This sculpture was moved after Donatello decided to leave Florence and make Siena his permanent home.

Donatello, John the Baptist, Cappella di San Giovanni Battista, Duomo, Siena, Italy, October 2011. Photograph by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

Cappella Chigi

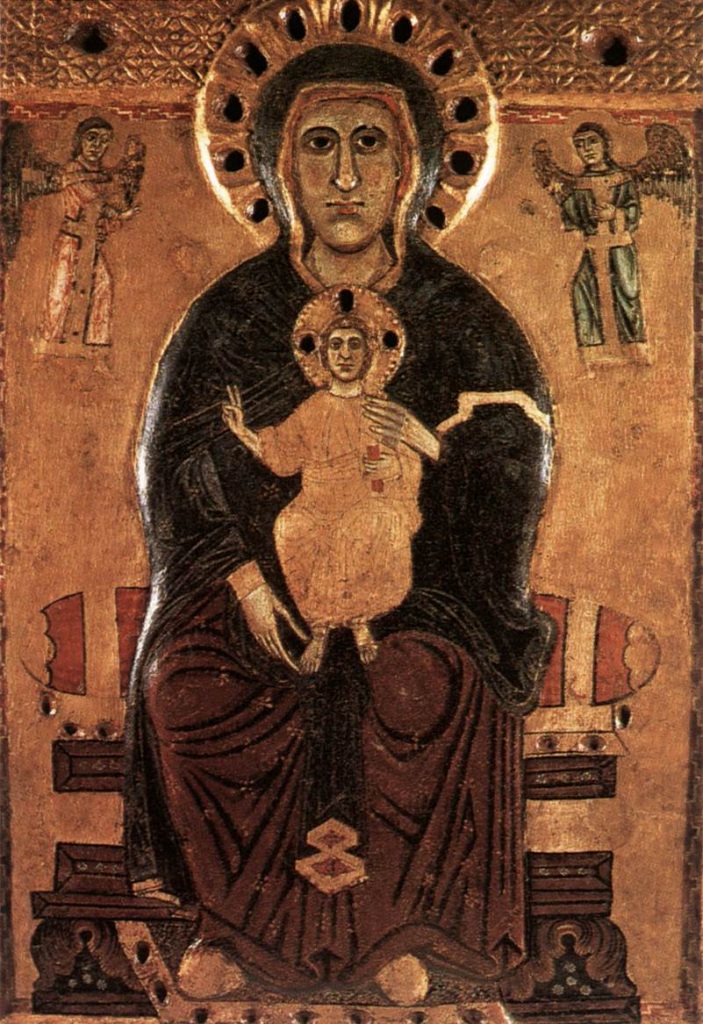

Located directly across from Cappella di San Giovanni Battista is the Cappella Chigi or the Chigi Chapel. Madonna del Voto, also known as Advocata Senensium, i.e., Advocate of the Sienese is believed to be the work of painter, Dietisalvi di Speme, however, this has never been confirmed. Madonna del Voto replaced the important Byzantine icon, The Madonna of the Wide Eyes, which is one of the most ancient works of the School of Siena, currently preserved in the Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo. Madonna del Voto occupies an important sanctuary located off the right transept of the Duomo of Siena.

According to tradition, the people of Siena promised to devote themselves to the Virgin before the battle of Montaperti in 1260. The Sienese people’s wishes were granted and they triumphed over the superior Florentine troops.

Since Madonna del Voto is believed to have been commissioned to Dietisalvi di Speme following the victory of the Sienese at Montaperti around 1270, it is likely that the vow of the Sienese people was made before Madonna del Voto’s predecessor, The Madonna of the Wide Eyes. Set on a backdrop of blue lapis lazuli, Madonna del Voto takes a place of prominence on the altar. The painting is set on a frame that is supported by bronze angels.

The painting was originally positioned in the right-hand nave of the cathedral, but around the 15th century, the Chapel delle Grazie was created to provide it with a more fitting location. Around the 17th century the Sienese-born Fabio Chigi, who ascended the throne of Peter as Pope Alessandro VII, commissioned Baroque artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini to build the Chigi Chapel. This is a rare example of Bernini’s work outside of Rome.

Bernini was the main architect responsible for the design of the Chapel and statuary. Bernini’s students created the sculptures of San Bernardino and St. Catherine of Siena, while Bernini himself created the famous sculptures in niches flanking the entrance depicting St. Jerome and Mary Magdalene to represent the chapels theme of penitence.

Battistero di San Giovanni

It is believed that the master builder, Camaino di Crescentino built either the Battistero di San Giovanni or the Baptistry of St. John between 1319 and 1325. While baptistries are generally placed in the front of a cathedral, in Siena it was placed behind and under the Duomo due to insufficient room in front of it.

The interior is divided into three rib-vaulted aisles complete with abundant frescos typical of Sienese art. The frescos, completed between 1447 and 1450, illustrate various themes of Christianity and are the works of Lorenzo di Pietro, known as “Vecchietta” as well as, to a lesser extent by Matteo Lambertini and Benvenuto di Giovanni. Unfortunately, these frescos were clumsily “restored” in the late 19th century, destroying their artistic quality.

View of Baptistry, Duomo, Siena, Italy, May 2009. Photograph by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

Taking a prominent place in the interior is the Baptismal Font, a marble, bronze, and enamel structure placed on a stepped hexagonal base. The Baptismal Font is a collaboration of the greatest sculptors of the era including Lorenzo Ghiberti, Giovanni di Turino, Donatello, and Jacopo della Quercia. On the base are six gilded bronze panels decorated with bas reliefs of scenes from the life of John the Baptist.

Donatello’s famous rendering of the Feast of Herod is depicted in bronze on the Baptismal Font. It is a gruesome biblical story that has been lauded as an early example of two-point perspective art that employs high and low relief methods. The panels are separated by carvings of the Virtues. The Virtues of Faith and Hope are also works of Donatello.

View of Baptistry, Siena, Italy, May 2009. Photograph by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

Facciatone

In around 1339, Siena planned a significant construction project that would have doubled the size of the structure. It involved the creation of a new nave over 300 feet (100 meters) long and two aisles perpendicular to the existing nave and centered on the high altar (with the original nave being reimagined as a transept). The construction was entrusted to the sculptor, Giovanni di Agostino. However, this project slowed down considerably after 1348, until it came to a complete halt when the Black Death swept through the city taking with it two-thirds of the Sienese population and the economic devastation that followed.

The incomplete façade called the Facciatone is visible at the south end of the Duomo and is all that remains of the ill-fated project. Today, it remains accessible and provides breathtaking aerial views of Siena. It survives as a monument of Siena’s former glory, ambition, and its tremendous artistic achievement.