5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

A lot of focus is put on the Renaissance when learning art history. It spans a few centuries and is known as a period of great change in European history. In contrast to the Middle Ages, interests in humans and ideals of antiquity were revived during that time. But how did this transition from two very different periods of European culture occur? Was it smooth? Well, that period of transition is called the Proto-Renaissance. It defines the years roughly from 1300 to 1400 CE, when artists such as Giotto introduced new artistic techniques, and philosophers emerged with thoughts on humanism.

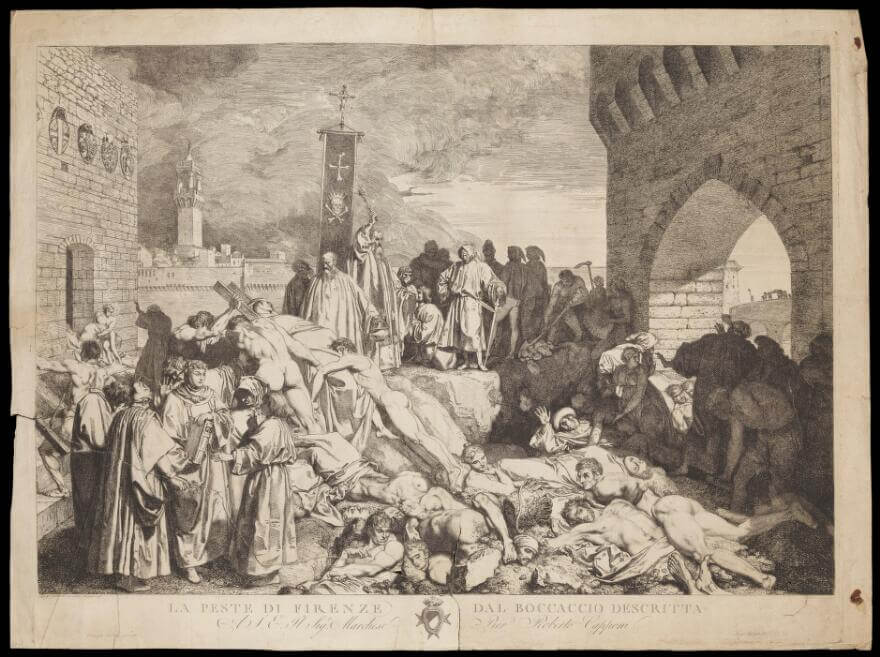

Overall, there was plenty happening on the European continent at the time, as a whole, and in Italy in general where Proto-Renaissance was born. There is much more to study once you peel back the figurative “curtain” of the Proto-Renaissance. Death tolls from the plague reached upwards of 25 and 50 percent of the European continent as a whole; rising higher in places where people lived in such close proximity. With death on their minds, many of the people during this period turned to religious practice. This tumultuous period is depicted in Dante’s epic Divine Comedy.

L. Sabatelli the elder (after G. Boccaccio), The Plague of Florence, 1348; an episode in the Decameron by Boccaccio, etching, Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

The Proto-Renaissance emerged in Italy, having started in Florence, that in those days was a powerful city-state. Much of what made up modern-day Italy’s history and culture during this period was centered on the rivalries between those city-states, republics and those ruling them.

The Italian city-states in 1499. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

City-states were regions independently ruled or governed all over Italy. And at times, these groups warred against one another. Italy was not a unified country back then. Beyond the different rulers, each city-state was known for its own trade(s): i.e. theater, visual art, literature, or ceramics. All city-states prospered in different and unique ways, especially Florence.

While the Renaissance began to filter through Italy, Florence is known as its birthplace. During this time, an influx of wealth flooded into this city-state. And these wealthy citizens could afford to commission art that reflected their religious, philosophical, and political ambitions. Furthermore, the work they financed was meant to uphold the values of great ancient cultures. Other powerful city-states were Milan, Florence, Pisa, Siena, Genoa, Ferrara, Mantua, Verona, and Venice. Within these cities were artistic guilds.

Guilds were associations of artisans and merchants existing since ancient times. These organizations regulated the artistic production within a city-state. Guilds allowed for a certain level of protection for the artists, as well as acted much like a modern day co-op, where resources could be shared. But it was more than a place where merchants, artists, and the like could prosper collectively.

Italian guilds originated as religious organizations that helped the poor and those less fortunate. In Florence, specifically in the first half of the 14th century, there were 14 Great Guilds (Arti Maggiori) and 7 Minor Guilds (Arti Minori). In order to practice your trade, or any trade for that matter, you had to be a part of the guild. There were guilds for wool workers, wool merchants, judges, bankers, silk weavers, and physicians, to name a few.

While Florence was home to many artists, they also thrived in other city-states like Siena and Milan. A few of these artists are mentioned below, beginning with Giotto di Bondone (c. 1267–1337) who is considered to be the father of Renaissance art.

Attributed to the Florentine School, Five Famous Men, portrait of Giotto di Bondone, ca. 1490, Louvre Museum, Paris, France. Detail.

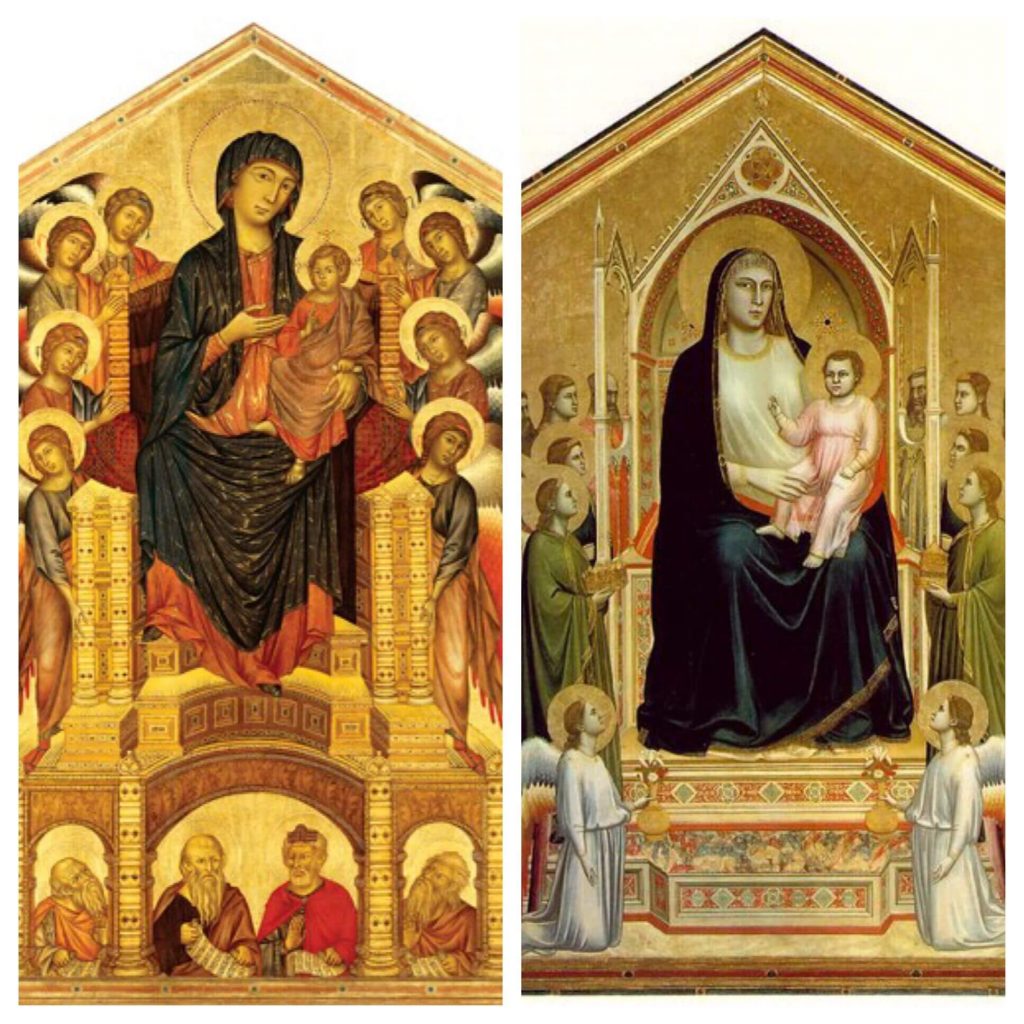

Though you can start to see a transition from medieval and Byzantine styles in the art of Cimabue, Giotto’s art is where you see it come to more defined fruition. According to Giorgio Vasari, Cimabue was Giotto’s teacher. Cimabue’s painting has the stiff heavier style of the Byzantine influence, with the figures all stacked one on top of the other. The artists turned to the technique of fresco painting which is still to be admired today. Fresco paintings did not fare well in places of high humidity. Therefore, it did not succeed in places such as Venice.

Left: Cimabue, Madonna Enthroned with Angels and Prophets, 1290, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy; Right: Giotto di Bondone, Madonna Enthroned (Ognissanti Madonna), ca. 1310, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

Giotto, in comparison to Cimabue, utilized the surface of his panel to create a more dimensional space. His Madonna and Christ sit back into the tall throne, surrounded by figures and angels who, instead of stacking together, rather recede more naturally into the background. While Giotto’s painting style transitioned, you can still see that remnants of the Byzantine style remained with his use of gold and the size-differentials of the angels and prophets to the center figures. From the depth and use of perspective, to the more natural depiction of the main two figures at the center of these Madonna and Christ Child portrayals, we can see the stylistic change slowly start to unfold.

Giotto di Bondone. Lamentation, ca. 1304-1306, from Scenes from the Life of Christ, located in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy.

Before Madonna Enthroned, Giotto painted a series of narratives in the Scrovegni Chapel, detailing the life of Christ. This monumental project secured him a reputation of the father of the Renaissance who paved the way for the rest of Italian artists to come.

Look at the depth of the painting, the natural movements, the way the angels appear to come straight out of the painting. And above all, look at the emotion of the figures. The shading and shadows cast by the robing and figures. All of these things were an integral part of the Proto-Renaissance.

Giotto hailed from Florence. And Simone Martini (c. 1284–1344) came from Siena. The Annunciation was a popular theme and Martini (and his co-artist Lippo Memmi) did it justice, creating a vivid narrative of the Biblical tale utilizing more natural movement and placement alongside a golden backdrop. The painting, created for the altar of St. Ansanus, was originally dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

The natural movement is most evident in the Archangel Gabriel. The painting captures the moment he appears to be landing and speaking to Mary within the same moment, as if his message can wait no longer. This naturalistic approach to the figures and use of the medieval altar structure combined shows a great example of the style moving forward out of the 13th and into the 14th century.

Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi, The Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus, 1333, Ufizzi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

Another artist of note was the leading figure in the school of Sienese painting, Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255/1260–c. 1318/1319). Though art historians do not have a lot of information on the artist, from what is known by the artworks attributed to Duccio, he was an important part of the bridge between the Byzantine and Renaissance styles. His most famous work of art is undoubtedly the Maestà altarpiece.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà Altarpiece, ca. 1308-1311, Siena Cathedral, Siena, Italy. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

This Maestà depicts the Virgin Mary and Christ child in the center surrounded by angels, prophets, and other biblical figures who are denoted by their nimbs (the golden halo surrounding the head), and was originally commissioned by the city of Siena in 1308. The altarpiece has since been deconstructed, with parts having been lost to time or placed in different museums throughout Italy. However, in its original state, it encompassed in this one altarpiece what would normally be seen on the walls of chapels as frescoes. Think of Giotto’s Life of Christ narrative in the Scrovegni Chapel of Padua. It is not small by any means.

With paintings on the front and back, the altarpiece spans roughly 7 feet by 13 feet (ca. 200 x 400 cm). Like Simone’s aforementioned altarpiece, Duccio’s use of gold is reflective of the Byzantine style. But it is his use of softer lines in figures and the use of natural shading in folds of garments that help to differentiate the artistic periods of which he worked between.

There is a plethora of other artists to consider when discussing Proto-Renaissance. Artists such as Ugolino da Siena or the brothers, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, created artworks that now hang in art museums around the world and as stationary pieces in the chapels of Italy. All of the artists above, combined with the ones listed here, deserve articles of their own, given the work they did to prepare ground for Renaissance masters, such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Michelangelo.

Fred S. Klener, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 2011, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Trans. Gaston du C. de Vere, Ed. Philip Jacks, Modern Library, 2006, New York, USA.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!