Biography

Let us start with a quick biography of Margaret Randall. Born in New York City, she has lived for extended periods in Spanish Seville, Cuban Havana, and Nicaraguan Managua, as well as in Mexico City. She has published more than 200 books in her lifetime and received a number of literary awards.

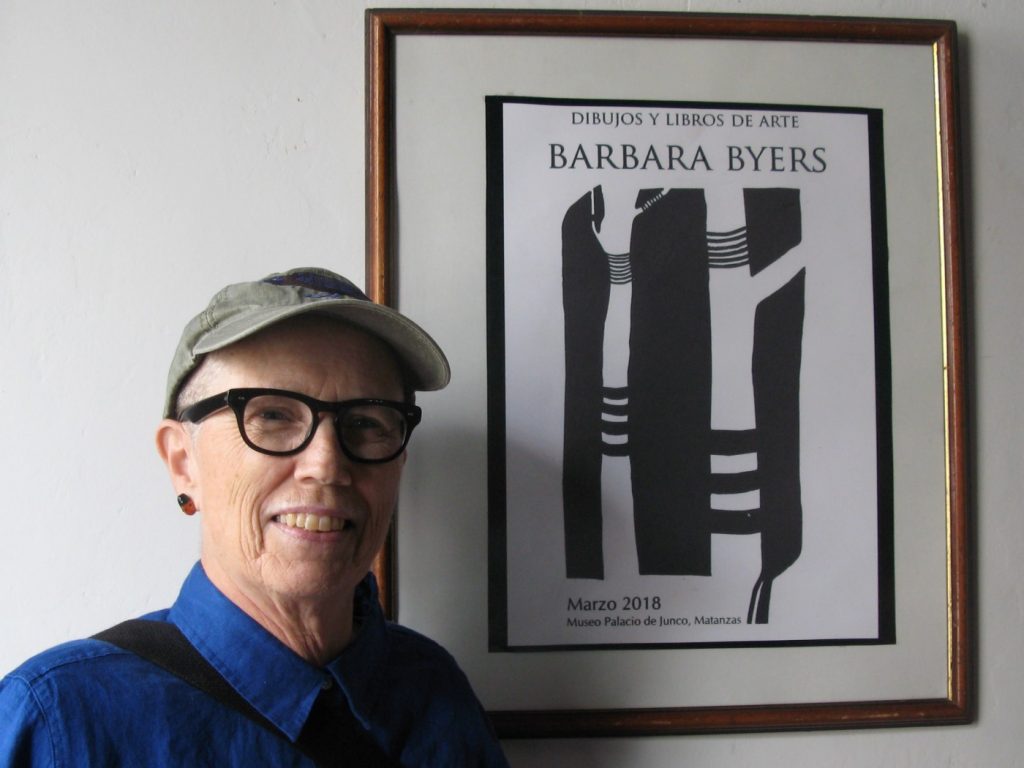

Randall returned to the USA in 1984, but the US government immediately tried to deport her. They claimed that her writing was subversive and that she should be exiled. That fight took five long years, with many famous writers and activists rushing to her aid. She finally won her case in 1989. Today, she lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the southwestern USA with her wife, a painter named Barbara Byers.

Radical Politics

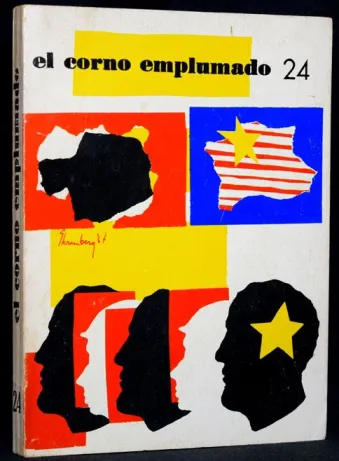

Margaret Randall found herself in some of the most politically turbulent moments in recent world history. In the 1950s, she lived in New York, working alongside the emerging Abstract Expressionist artists. In the 1960s, in Mexico City, she co-founded and co-edited El Corno Emplumado (The Plumed Horn), a bilingual literary journal. Over an eight-year period, this magazine published some of the most dynamic writing of the era. She participated in the Mexican student movement of 1968. She lived in Cuba during the second decade of the Cuban Revolution (1969-1980), lived in Nicaragua during the first four years of the Sandinista project (1980-1984), and visited North Vietnam during the last months of the American war in 1974.

In the book, we have 12 separate chapters, each covering a different artist. But this is not your average art history academic text. Instead, Margaret Randall offers us intimate and personal recollections and revelations. She explores just how an individual artist or an individual work of art has affected her personally and professionally. And she tells us how those artists and works live with her, and continue to impact upon her. This is an honest exploration of how art impacts an individual – socially, artistically, spiritually.

The Artists

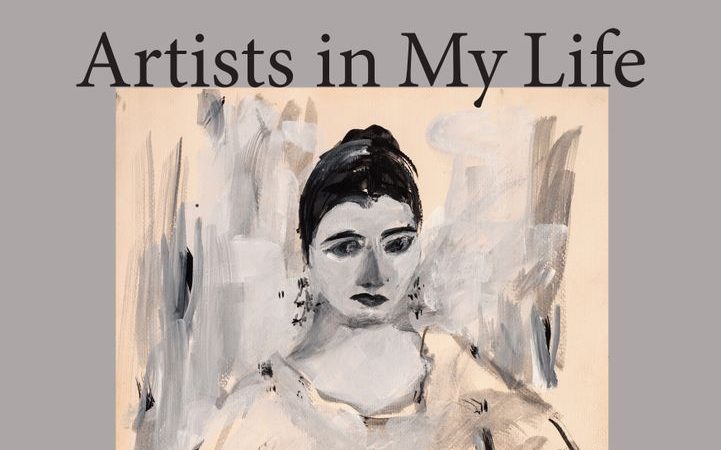

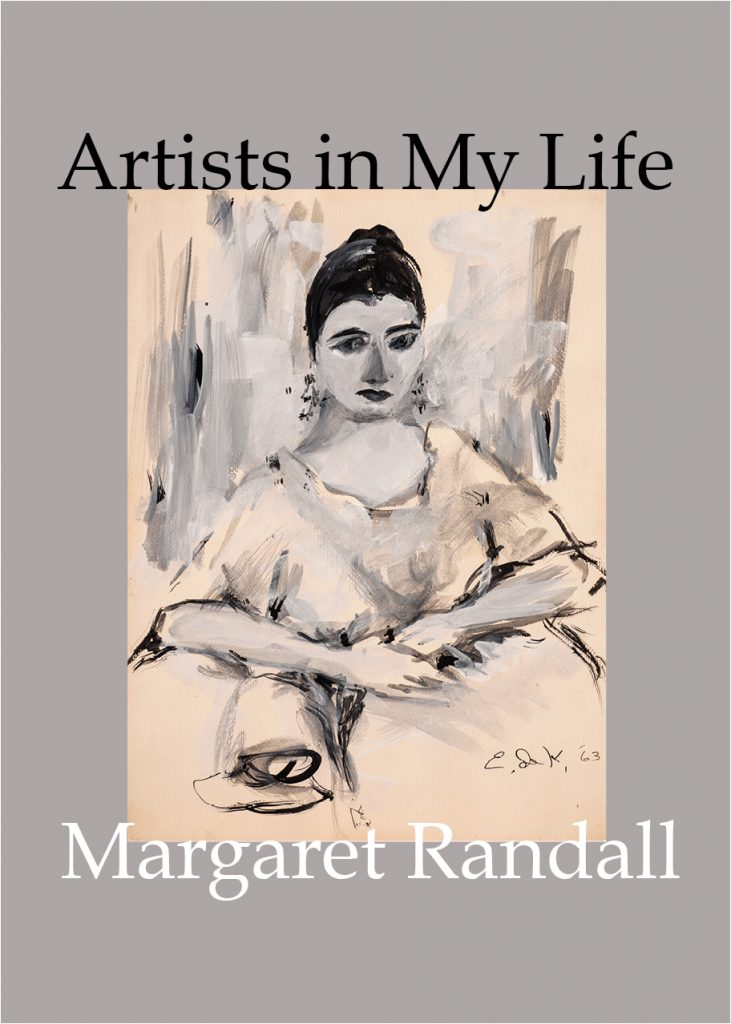

Some of the names in the book will be familiar: Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe. Others will possibly be new to us: Sabra Moore and Jane Norling. Almost all of the artists chosen are women. However, one is a man, one is an artist family, and one is a male/female working partnership. We even take a look at the unknown creators of 10,000-year-old petroglyphs in Peru. We see painters, sculptors, architects, and photographers. Elaine de Kooning’s work has been chosen as the cover image: a 1960s ink and gouache portrait of Margaret Randall, titled Meg Randall.

Art As Social Activism

Margaret Randall looks at the works produced by her favorite artists. She analyses them intelligently. But we also gain insight into what was driving these people, and their impact on the wider art community. Randall is interested in placing art within a social context: how women artists are treated in a world dominated by the patriarchy and male values. But she also explores how women resist and create community with their art. Art as radical statement and art as social activism are themes that run throughout this book.

Big Questions

This is an immensely personal book. It is honest and frank, and written in a very easy-to-follow conversational style. Even if you don’t feel drawn to one of her chosen artists, you can simply slip on into the next chapter. Randall gets up close and personal with these artists, many of whom are close personal friends, but she asks the big questions:

Elaine de Kooning

As some of these artists are very close friends, there is sometimes a tendency to gloss over difficult areas. For instance, in Randall’s treatment of Elaine de Kooning. This artist was famously dismissive of the idea that looking at artists as “women” was useful. She promoted the work of her husband, Willem de Kooning, at the expense of her own talent.

Randall claims her friend was born “before the issue of gender was on our cultural radar.”1 However, De Kooning was born in 1918, when women (suffragettes), who had been fighting very vocally for rights and votes, finally pushed through the Representation of the People Act in the UK. This and many other political struggles by women were widely publicized across the USA.

Problematic Friendships

Randall claims that De Kooning had a primal and uncomplicated passion for men. Today, we may feel that this “passion” was in fact really very complicated. Randall states: “She was not privy, that I know of, to the discussions – still several decades into the future – about misogyny.”2

Could it be true that intelligent, curious people at the heart of a radical arts movement were not aware of wider social issues? Surely not. It feels dangerously close to the kind of apolitical talk people use today to excuse the misogyny, racism and child abuse of the past. It was a different time, they usually exclaim, we didn’t know lynchings and sending children up chimneys was wrong! We didn’t know burning witches and beating our wives was inappropriate!

Yes, of course, Elaine de Kooning did grow up in a different era, but many people were very publicly and vocally challenging gender norms and patriarchal rules during her lifetime. If Elaine de Kooning chose not to look or listen, then that is a problem that can’t be swept under the rug in the name of friendship. Especially by a woman like Margaret Randall, who has spent her life championing the rights of women across the globe.

This is a fascinating and extraordinary book. As we journey through the chapters, Randall shares a glimpse into the journeys of her own life, and what sustains her as an artist and as a woman. Art, politics, and sense of place are all one for Randall. Her revolutionary life is well worth a look.

Make sure to get your own copy of Artists in My Life here.