Masterpiece Story: Wheatfield with Cypresses by Vincent van Gogh

Wheatfield with Cypresses expresses the emotional intensity that has become the trademark of Vincent van Gogh’s signature style. Let’s delve...

James W Singer 17 November 2024

4 September 2024 min Read

Monarch of the Glen by Edwin Landseer is one of the most famous British paintings of the 19th century. It is a Victorian melodrama at its most delicious.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK.

England and Scotland have a complex and intertwined history. They have developed a love-hate relationship which stems from their centuries of political, economic, and social differences. However, this tenuous relationship achieved a Pax Britannica (British Peace) during the 19th century with the personal influences of Queen Victoria and Sir Edwin Landseer.

Scotland became Queen Victoria’s favorite vacation destination with its wild landscapes, fresh air, and hearty food. Edwin Landseer became the Queen’s favorite artist because he too visited and valued the Scottish lands and appreciated their raw majesty. With the Queen and the artist promoting Scotland’s charms, the Victorian English soon grew to appreciate their northerly neighbor. Monarch of the Glen is Landseer’s masterpiece, and it encapsulates the Victorian English-Scottish relationship like no other British painting of the 19th century.

Francis Grant, Portrait of Sir Edwin Landseer, 1852, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK.

Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) painted Monarch of the Glen approximately in 1851. The almost-square oil on canvas measures 164 cm high by 169 cm wide (5 ft 4 in high by 5 ft 7 in wide). It depicts a single stag, a male deer, as it rises from a foreground of wispy heather against a background of swirling mist and rocky mountains. The stag has a majestic air as it surveys the surrounding land. Perhaps the animal is scouting for female companionship or guarding against male rivals or human hunters?

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

Outside hunting circles and wildlife enthusiasts, many people are unaware that a deer’s age is reflected in the number of antler horns. More antlers indicate a greater maturity. The stag depicted in the painting has 12 antler horns or points which classifies him as a royal stag. If he had 14 points, he would be an imperial stag, and with 16 or more points, he would be a monarch. Therefore, the painting should really be called Royal of the Glen because the depicted stag does not have the requisite number of horns to be called a monarch. Was Landseer unaware of the stag classifications, or did he use “monarch” under artistic license since it creates a more poetic title?

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

Edwin Landseer had a troubled later life with episodes of depression, alcoholism, and drug addiction. Towards the end of his life, he displayed mental instability, and he was declared insane in 1872 at the request of his family. Despite his personal challenges and hardships, Landseer was professionally a great success. He was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1850, had several pieces commissioned by her, and he was accepted by the Royal Academy. When Monarch of the Glen was painted, Landseer was at the height of his popularity and renown. The painting merely cemented his reputation as a masterful draftsman and painter.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

Romanticism radiates from the painting. Romanticism was an artistic movement of the 19th century when great emotions and feelings were valued over reason and logic. Famous examples include Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) and J. M. W. Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed (1844). The Romanticism of the Scottish highlands is conveyed through the stag’s isolated grandeur and the windswept moors. The blustery mountains convey Scotland’s raw kinetic energy while the motionless stag conveys Scotland’s hidden potential energy. Activity and inactivity create a wonderful visual contrast upon the canvas.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

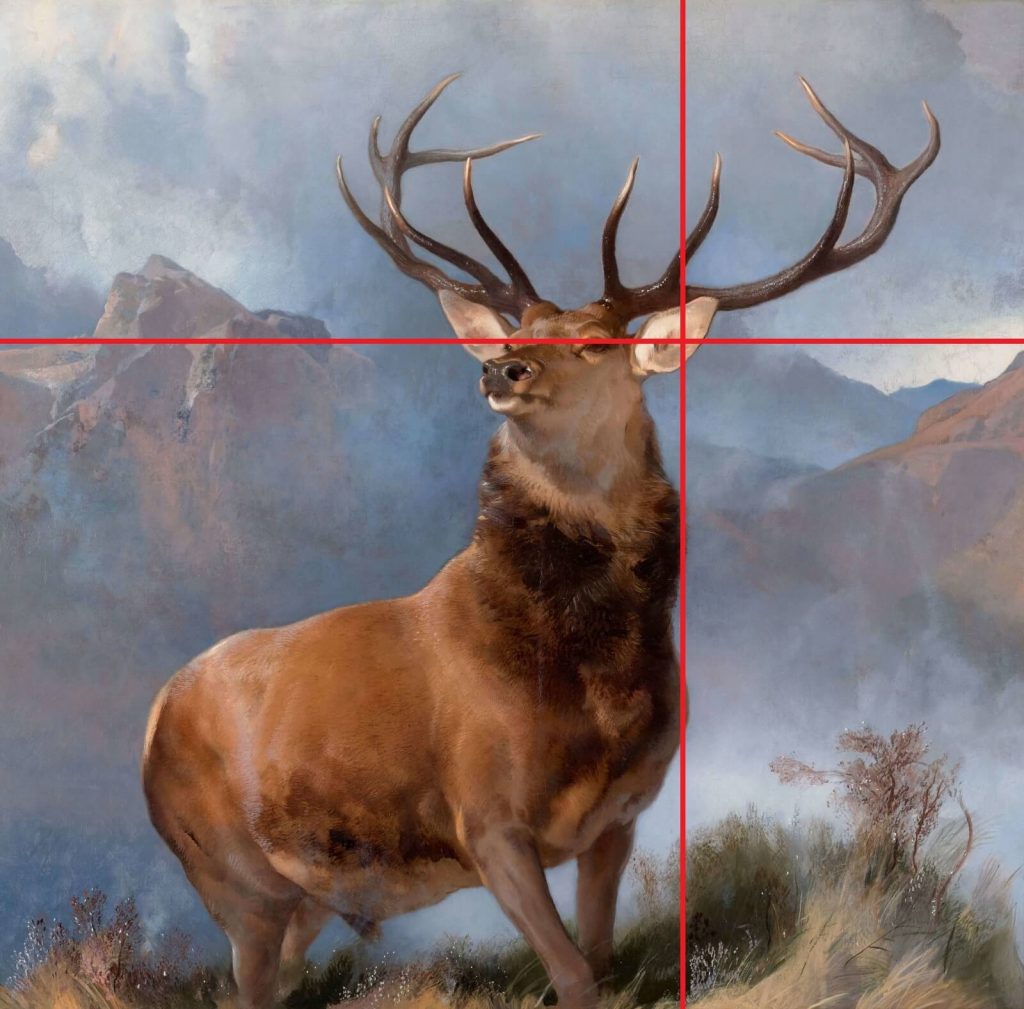

Monarch of the Glen uses the ever-famous rule of thirds to construct its composition. The rule of thirds has been used for centuries by visual artists to infuse imbalance and interest into their visual works. The rule of thirds dictates that major edges or focal points should align one-third from a composition’s boundary. If one-third overlays are placed on Monarch of the Glen, the rule becomes very apparent. The deer’s right edge aligns with the one-third vertical line, and the deer’s eyes align with the one-third horizontal line. Edwin Landseer was a master draftsman, and he used this principle throughout many of his works, including Monarch of the Glen.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, One-third overlay, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK.

The painting is a technical masterpiece. Edwin Landseer shows a great sensitivity to the painting’s details from the feathery lightness of the heather, through the glossy fur of the deer, to the shadowy volumes of the mountains. Individual brushstrokes can be seen to create the overall impressions of light playing across textures. It is a very tactile painting with various intensities of softness and hardness. Organic and inorganic elements add further complexity as Landseer masters depicting the living animal and plants with the lifeless winds and mountains. Such a visual recipe creates an unsaid attraction to the work. The viewer is drawn to the animal like a contemporary wildlife observer. The spectator knows it to be wild and potentially dangerous, but it has a graceful beauty that enchants the viewer.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

Monarch of the Glen captivates the contemporary audience with the same intensity as it did the Victorians. During the 19th century, the painting was reproduced in prints and engravings. Contemporarily, the painting is used in advertisements and company brands. Many modern Scottish companies use the stag’s iconic outline for their products such as Scotch whiskey and shortbread biscuits. Monarch of the Glen has even been used as the title of a British drama television series (2000-2005). The name and image are synonymous with Scotland.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

Some modern viewers, however, take a very negative stance against the painting’s iconic reputation. Some modern historians view the painting as cultural imperialism since it was an English Queen and an English artist who popularized their interpretation of a Scottish national identity. Some Scots resent that an icon of Scotland was painted through the lens of a visiting Londoner. Landseer went to Scotland every year for 49 years from 1824 to 1873. However, this lifelong appreciation of the country still does not make Landseer a Scottish artist. He was born in London, lived and worked in London, and he died in London. He was English from beginning to end.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

Additionally modern viewers resent the painting’s implied class commentary. According to most British aristocrats, stags are meant to be hunted by the local country gentry. A stag found wandering on the gentry’s land is considered the gentry’s property and within the gentry’s right to kill. Local tenants did not own the right to hunt stags, and they were penalized if caught poaching.

Local Scottish gentry further increased their territorial rights through the Highland Clearances that lasted a century from the 1750s to the 1860s. During the Highland Clearances, many Scottish gentry evicted tenants, enclosed open land, and restructured agricultural practices. It was a time of great resentment for the landless poor towards the landed rich. Therefore, some modern viewers interpret Monarch of the Glen as a glorification of class warfare. It represents the rich enjoying their privileged hunting games over the poor suffering their painfully destroyed livelihoods.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

Despite some modern controversy, Monarch of the Glen is still a well-loved image with international fame. It is one of the most famous British paintings of the 19th century. It is a Victorian melodrama at its most delicious. It is a symbol of Scotland. There is no surprise that Monarch of the Glen continues to draw crowds. It is controversial. It is beloved. It is British.

Edwin Landseer, Monarch of the Glen, ca 1851, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK. Detail.

Lachlan Goudie: “Monarch of The Glen: The Creation of an Icon.” Features. Scottish National Gallery. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

“Monarch of the Glen.” Collection. Scottish National Gallery. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

“Sir Edwin Landseer.” Artists. Scottish National Gallery. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

“Sir Edwin Landseer.” Collection. National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!