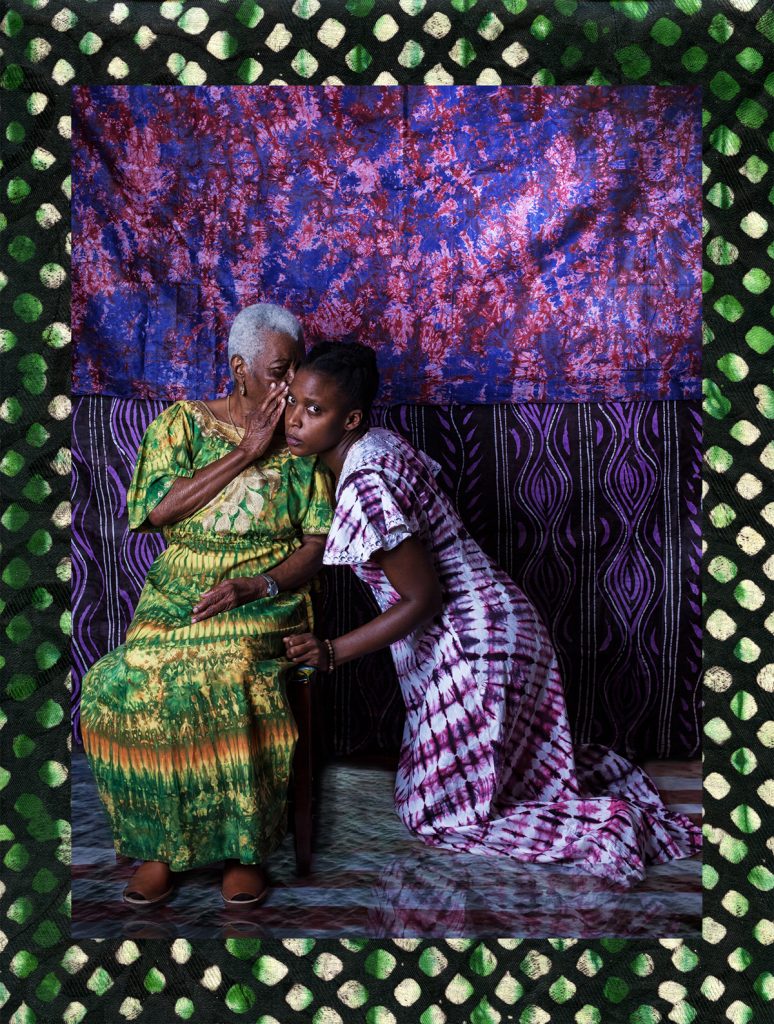

Cover of Black Matrilineage, Photography, and Representation: Another Way of Knowing, edited by Lesly Deschler Canossi and Zoraida Lopez-Diago, Leuven University Press, 2022, artwork by Andrea Chung.

Black Matrilineage

Black Matrilineage, Photography, and Representation: Another Way of Knowing advances the mission of Women Picturing Revolution as founded by Lesly Deschler Canossi and Zoraida Lopez-Diago to expand the framework around women in photography. The publication of this book is noteworthy for its focus on Black motherhood, a subject most deserving of the intellectual rigor and affectionate discourse running throughout this thoughtfully curated set of essays and photographs. The discussions span the photographic practices of the past century, filtered through current events such as the global pandemic and the public outcry against the inexcusable and state-sanctioned violence that has persisted against Black populations around the world.

Black Matrilineange examines representations of Black motherhood as they appear across current media outlets. They are constructed through professional portrait practices, utilized in the healthcare sector and studies of mass incarceration, created for private consumption, and revolutionized by artists who explore Black matrilineage with photography. Divided into four sections and followed by a curated set of color reproductions, the central theme of this book rejects the degrading and condemning narratives that have dominated popular representations of Black motherhood.

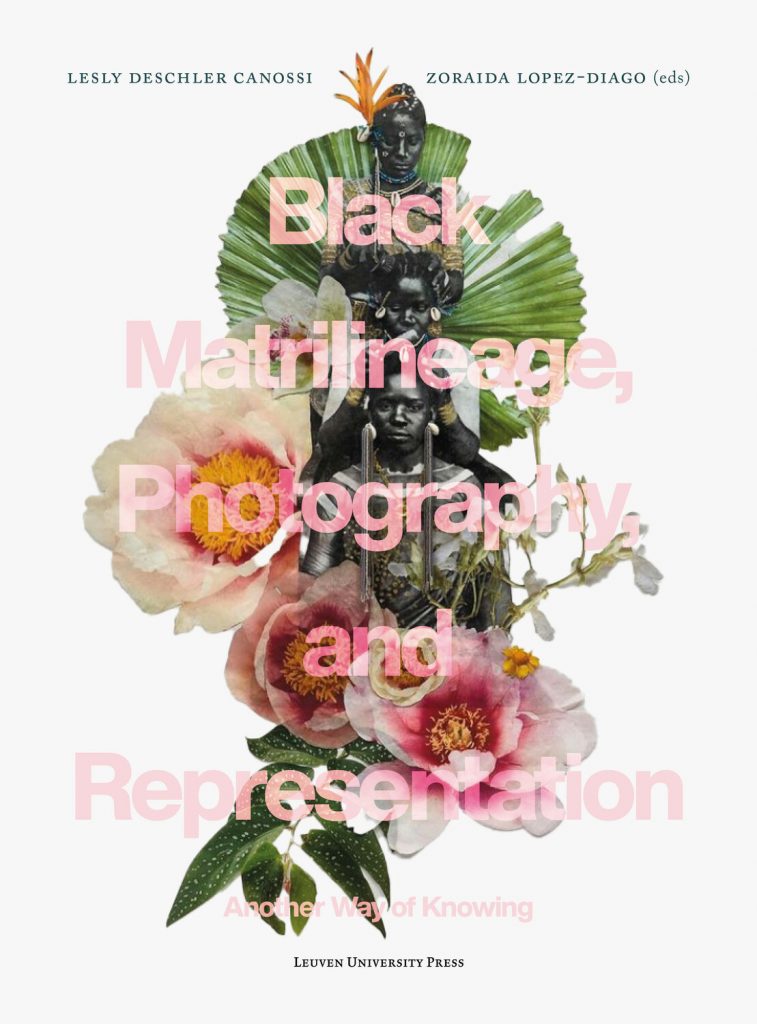

Deborah Willis, I Made Space for a Good Man, 2009. Courtesy of the RISD Museum.

This critical and revisionist framework is supported by the scholarship of Patricia Hill Collins and her groundbreaking book Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment which outlines the controlling images of Black motherhood. The essays of Black Matrilineage build upon Collins’ argument that Black motherhood has been narrowly constrained by images perpetuating racist stereotypes such as the mammy, the matriarch, the welfare queen, the baby mama, and the jezebel, all of which can be traced back to the transatlantic slave trade. These controlling images support racist propaganda and government policies that continue to deprive Black mothers of basic social services, adequate healthcare, equal justice, and access to an array of other support systems. In addition to Collins, the essays draw upon a matrilineage of Black feminist thought including the writings of Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Walker, bell hooks, Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, and Deborah Willis.

Portraits

In a concise and revelatory history of professional Black women photographers who ran their own portrait studios during the earlier half of the twentieth century, Emily Brady looks at how women such as Wilhelmina Pearl Selina Roberts, Elnora Teal, and Florestine Collins used their profession as a subtle form of activism. These women ran businesses in Black communities and contributed to the use of portrait photography to reflect wholesome family values and notions of respectability established by the white upper classes. Restricted to the space of their studios, these women used props, elegant furniture, and fancy clothing to fashion portraits reflective of their sitters’ racial and class aspirations. These portraits, created exclusively for the display in private homes, illustrate some of the traditional methods used within Black communities to redefine themselves through photography. This private use of photography informs more recent projects by Black feminist artists who are rethinking representations of Black motherhood for the public sphere.

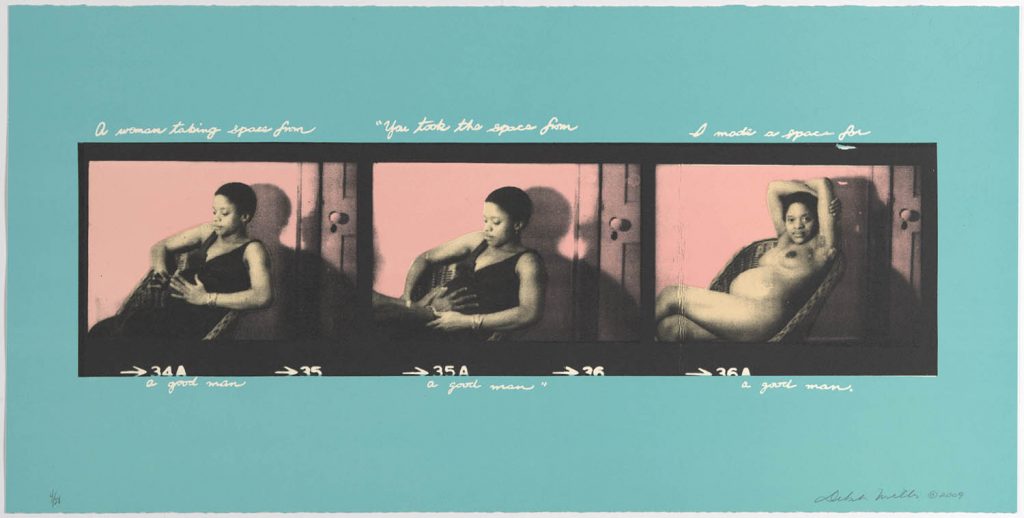

Renee Cox, Yo Mama, 1993. Gelatin silver photograph, Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Carol and Arthur Goldberg Collection. © artist Renee Cox

The groundbreaking work of artists Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1953) and Renee Cox (b. 1960) paved the way for the subject of Black matrilineage to be considered by contemporary artists. In the series Family Pictures and Stories from the late 1980s, Weems captured private, intimate, and joyful moments shared by members of the artist’s family. In the 1990s, Cox emboldened the concept of Black motherhood with her Yo Mama photographs, a series of tableaux presenting Black women as empowered superheroes. These series of photographs subvert misconceptions of the white patriarchy and widen the potential for Black matrilineage discourses to be developed by the next generation of artists. Black Matrilineange updates the conversation around the history of photography through its inclusion of contemporary Black feminists artists such as Deana Lawson (b. 1979), Andrea Chung (b. 1978), Nydia Blas (b. 1981), Nona Faustine (b. 1977), Marcia Michael (b. 1973), Zanele Muholi (b. 1972), Keisha Scarville (b. 1975), and Adama Delphine Fawundu (b. 1971).

Nydia Blas, Untitled, Revival, 2019, courtesy of the artist

The trappings of traditional portraiture are radically rethought in the contemporary work of artist Deana Lawson who readily explores themes of motherhood in seemingly candid yet carefully constructed photographs. In conversation with Lawson, Susan Thompson’s essay discusses a selection of Lawson’s photographs that captivate for their portrayals of the Black maternal experience. Mama Goma, Gemena, DR Congo (2014) is an elegant depiction of a young pregnant woman wearing a blue dress with a cut-out that exposes her belly and accentuates her beauty. Baby Sleep (2009) is a provocative look at the juxtaposition of sexuality and motherhood. This photograph captures a moment of passion between a nude woman straddling her male lover while their baby sleeps nearby. Similar themes run through the photographs of the artist Nydia Blas who intertwines a magical sense of spirituality into depictions of women at various stages of life. Untitled, Revival (2019) shows a woman near the end of her pregnancy standing with her belly exposed, wearing only a black fur cape and black briefs, and her head thrown back as if caught in a moment of rapture. These photographs affirm the multidimensionality of Black motherhood that in turn expands the possibilities for conceptions of Black matrilineage to move away from the limitation created by binaries such good mother/bad mother, oversexed/asexual and deserving/underserving.

Andrea Chung, Crowning I, 2014, collage, ink and color pencil, 14 x 11 inches (35.6 x 27.9 cm). Courtesy of the artist.

Healthcare & Mass Incarceration

Black Matrilineage makes room for discussion of the Black maternal healthcare justice movement and efforts to correct a deeply biased system where the health and well-being of Black mothers and babies are not guaranteed. Representations of motherhood within the healthcare sector have been reluctant to include Black women, resulting in a visible void that has perpetuated a system of unequal care. Haile Eshe Cole looks at representations of Black motherhood as filtered through such concerns as does Nicole Caruth. In conversation with Caruth, the artist Andrea Chung and Public Health Administrator D’Yuanna Allen-Robb discuss the potential of the meaningful exchange of ideas and imagery between artists and healthcare facilities. Chung’s Midwives series, begun in 2017, honors the practice of Black midwives that reaches back centuries throughout the African diaspora. These photographic collages combine archival photos of Black granny midwives from the American South and Caribbean and of children overlaid with forms referencing the female reproductive system, the use of medicinal herbs by these practitioners, and other symbols in acknowledgment of a tradition imbued with spirituality. Chung’s series also recognizes the expertise and wisdom of Black women birth workers, a well of knowledge that has been exiled by the developments of western medicine and healthcare systems that do not properly support the reproductive health of Black communities.

The subject of mass incarceration and the impacts of this deleterious system on multiple generations of Black families nationwide is another topic of discussion in Black Matrilineage. Atalie Gerhard’s essay analyzes the use of portraiture in recent academic studies of Black mothers who were or are currently incarcerated. Lawson’s series Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family (2013), is included in Thompson’s discussion as an example of mothering under difficult conditions. This series of photographs was appropriated by Lawson from the Facebook account of her cousin who regularly shared family portraits during visits to her boyfriend who eventually became her husband at a correctional institution. Over several years, their family grows while the husband/father remains incarcerated. The family portraits taken during the visits reflect the mental fortitude of a woman maintaining a family unit through the use of photography to create special memories despite the prison setting. Lawson’s installation of images extracted, with consent, from a social media account recognizes the coping mechanisms used to manage the challenges unique to Black mothers.

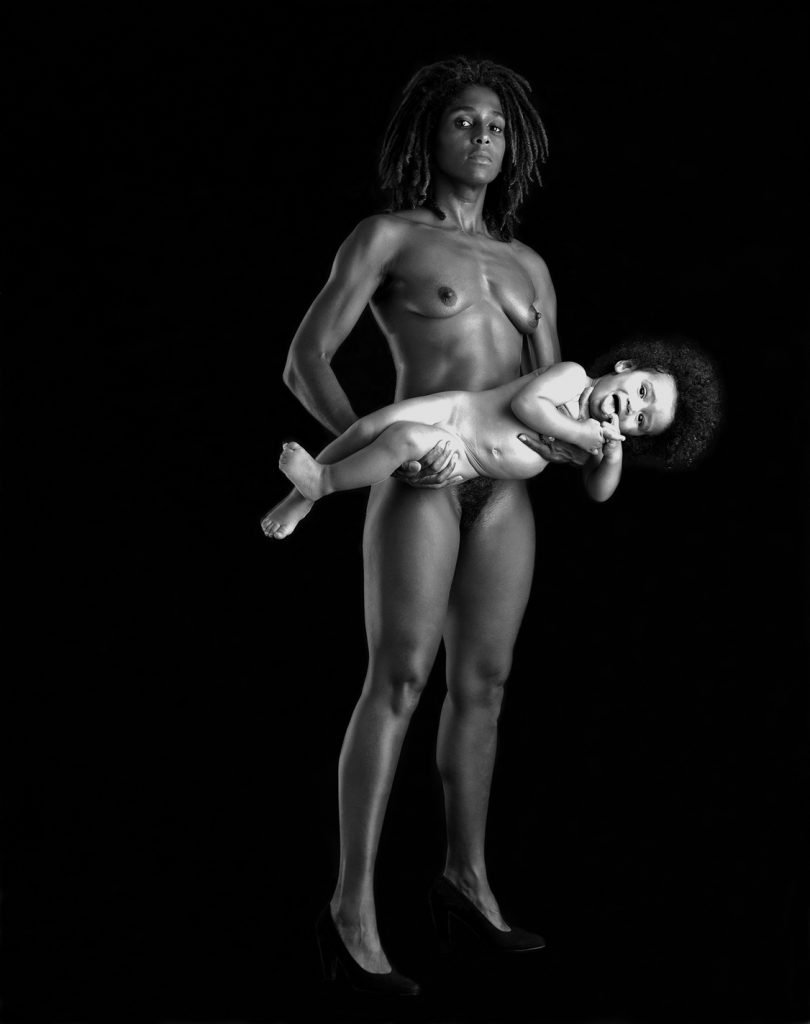

Nona Faustine, End of Baby Days, 2012, courtesy of © Nona Faustine, courtesy of the artist.

Conjuring the Past

Committed to understanding the traces of history as they impact representations of Black motherhood today, Black Matrilineage includes artists whose work is centered around making visible intangible pasts with photography. Jonathan Michael Square discusses Nona Faustine’s series Mitochondria, begun in 2008, as based on the artist’s exploration of maternal lineage. This series of photographs was taken in the Brooklyn home shared by the artist, her mother, her sister, and her daughter. In honor of the intimate bonds of this multigenerational family, this series is part of the artist’s larger project of tracing her ancestry back through the period of slavery in the United States and beyond to precolonial Africa. This collection of tender family photographs that are meant to be circulated in the public sphere, gives agency to representations of Black matrilineage that validate the intimacy of matriarchal relationships such as those seen in the photographs of Adama Delphine Fawundu.

Marcia Michael, Partus Sequitur Ventrem from the series The Object of My Gaze (2015-ongoing), courtesy of the artist.

Adama Delphine Fawundu, Passageways #1, Secrets, Traditions, Spoken and Unspoken Truths Not, 2017, courtesy of the artist.

Faustine has developed the subject of matrilineage through photographing the Black female body, as she uses her own in the White Shoes series (2012-2021) to reconnect with enslaved ancestors and to activate locations around New York City that are historically linked to the slave trade of the 1800s. Using the body of the Black woman to access Black matrilineage as a means to reconstruct one’s history or access the stories of one’s ancestors, is a method also used in the photography of Marcia Michael. Michael’s essay explains her own artistic process of photographing herself and her mother, whose Jamaican culture and upbringing exposed her to the ritual art of conjuring. This spiritual form of passing stories from mother to daughter is commonly practiced through folk art and craft traditions but also moves through the body and Michael used her camera to understand the teachings of her mother. In her ongoing series The Object of My Gaze, begun in 2015, Michael uses her camera to understand the body as an archive, a vessel containing the stories of her ancestors, to conjure the past. Black matrilineage opens discussions of photography to include numerous untold or unknown stories as in the case of Faustine and Michael who search their own bodies and those of their loved ones to fill in the blanks of individual and collective histories.

Zanele Muholi and Keisha Scarville also use photography to gain a deeper understanding of their mothers or foremothers’ experiences that venture into themes of migration and the politics of apartheid in South Africa. In her ongoing project Somnyama Ngonyama, Muholi uses herself in high contrast black and white photographs to embody the beauty of her mother as well as to connect with the tumultuous history of her motherland in South Africa. In conversation with Renée Mussai, Muholi explains how her photographs address the struggles of mothers who fought for equal justice and were subsequently incarcerated during apartheid. Furthermore, the images depict the daily grunt work performed by her mother and many others who are never given the opportunity to live up to their full potential. Muholi’s photographs are lush and irrefutably beautiful, yet sly in her use of everyday cleaning objects to adorn herself and the selection of unglamorous locations that link the artist to uncomfortable moments from the past.

Keisha Scarville, Mama’s Clothes, 2020, courtesy of the artist.

The magnitude of migration from one’s motherland, whether it was forced and without consent or done out of necessity to escape poverty, violence, or any other number of reasons, is explored in Grace Aneiza Ali’s essay discussing the photographs of artist Keisha Scarville. Ali moved to the United States from Guyana as a child meanwhile Scarville, also Guyanese, is a first-generation American and both women share feelings of longing for a homeland, expressed by Scarville in her series Mama’s Clothes, 2020. Ali works through feelings of displacement felt by immigrants and their children in her discussion of Scarville’s photographs. This series depicts the artist wrapped in the colorful fabrics of her mother’s clothing on location around her home in the U.S. and her motherland following the passing of her mother. Seeking to embody the essence of her mother’s migration from Guyana to New York City in the 1960s, Scarville circles around the cultural rupture experienced by her mother, especially as it is felt by the mind and body of the artist.

Conclusion

The publication of Black Matrilineage, Photography, and Representation: Another Way of Knowing is an invaluable resource that makes space for the experiences and stories of motherhood to be examined and celebrated. This discussion of Black matrilineage in photography consciously moves away from the controlling images that have limited representations of Black motherhood in popular culture. It also enhances not only the discourse around the history of photography but shows the potential for the mainstream to open up new pathways for the representation of Black motherhood that can affect change across various systems and hopefully improve real-life conditions for Black mothers.

The author and DailyArt Magazine would like to thank Lesly Deschler Canossi and Zoraida Lopez-Diago of Women Picturing Revolution as well as Leuven University Press for their generosity and time. To celebrate the launch of this book, there will be a panel event at the University of Oxford, Rothermere American Institute, on March 9, 2023.

Adama Delphine Fawundu, Passageways #2, Secrets, Traditions, Spoken and Unspoken Truths or Not, 2017, courtesy of the artist.

Recommended Articles:

In Their Shoes: Nona Faustine’s White Shoes

Black Feminist Photographers Fighting for Social Inclusion of Marginalized People

Five Black Female Artists You Should Know

Portraits by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: They Are Black Because I’m Not White

Masterpiece Story: Queen Mother Idia of Benin