Heterosis: Metaverse Garden

Heterosis allows users to hybridize and cultivate bespoke animated digital flowers that grow in a hyperrealistic metaverse garden.

The project features two major components: a collection of breedable, dynamic NFT flora and the “Greenhouse,” an extraordinary virtual reimagining of London’s National Gallery after the apocalypse. All the digital flowers in the collection grow in their current forms among the abandoned, overgrown remnants of this historic building.

Through innovative technology, the artwork invites collectors to play an adventurous game while simultaneously questioning the fundamentals of the blockchain space as a whole. Heterosis could not exist in any context other than the blockchain, relying as it does on multiple participants bringing the artwork to fruition.

In an interview, Mat Collishaw (b. 1966) shares the story behind the project, where he finds inspiration for his artworks, and how he uses technology in his art.

Mat Collishaw: As you know, I’m a visual artist, and I work with lots of different subjects and mediums, from photography to oil painting, virtual reality, optical illusions, animatronics, and more. I always try to find the medium that best suits the idea that I want to explore. I’ve worked with flowers for many years in many different forms, and I always use flowers as a means to express a particular idea that’s come to me. I became aware of the NFT space a few years ago, and I got interested in doing something there. NFTs struck me as an interesting new form for exhibiting my work, and to take advantage of them, I wanted to develop a project that engages with them as entities completely different from our analog world.

I was wondering how I could develop a project that would live online. The situation begged an obvious comparison between NFTs and Tulipmania, given how the prices of NFTs started getting crazy starting in 2021. There was a lot of speculation, and Tulipmania constantly came up as a comparison. I saw this as an interesting possibility; I’m interested in flowers, I work with them frequently, and I spent a lot of time reading books about this phenomenon from the 17th century. The more I read, the more interesting it became.

Most importantly of all, after the spike and crash of 1637, people carried on buying tulips for another 100 years until hyacinths eclipsed them in popularity. By extension, the ups and downs we’ve had in the NFT world are not necessarily the end of the game. It’s a natural process of clearing out. Everybody suddenly jumps in, prices go crazy, and then things return to normal.

Mat Collishaw. Courtesy of the Artist.

Agnieszka Cichocka: Mat, tell me a bit more about your latest project, Heterosis.

Mat Collishaw: As you know, I’m a visual artist, and I work with lots of different subjects and mediums, from photography to oil painting, virtual reality, optical illusions, animatronics, and more. I always try to find the medium that best suits the idea that I want to explore. I’ve worked with flowers for many years in many different forms, and I always use flowers as a means to express a particular idea that’s come to me. I became aware of the NFT space a few years ago, and I got interested in doing something there. NFTs struck me as an interesting new form for exhibiting my work, and to take advantage of them, I wanted to develop a project that engages with them as entities completely different from our analog world.

I was wondering how I could develop a project that would live online. The situation begged an obvious comparison between NFTs and Tulipmania, given how the prices of NFTs started getting crazy starting in 2021. There was a lot of speculation, and Tulipmania constantly came up as a comparison. I saw this as an interesting possibility; I’m interested in flowers, I work with them frequently, and I spent a lot of time reading books about this phenomenon from the 17th century. The more I read, the more interesting it became.

Most importantly of all, after the spike and crash of 1637, people carried on buying tulips for another 100 years until hyacinths eclipsed them in popularity. By extension, the ups and downs we’ve had in the NFT world are not necessarily the end of the game. It’s a natural process of clearing out. Everybody suddenly jumps in, prices go crazy, and then things return to normal.

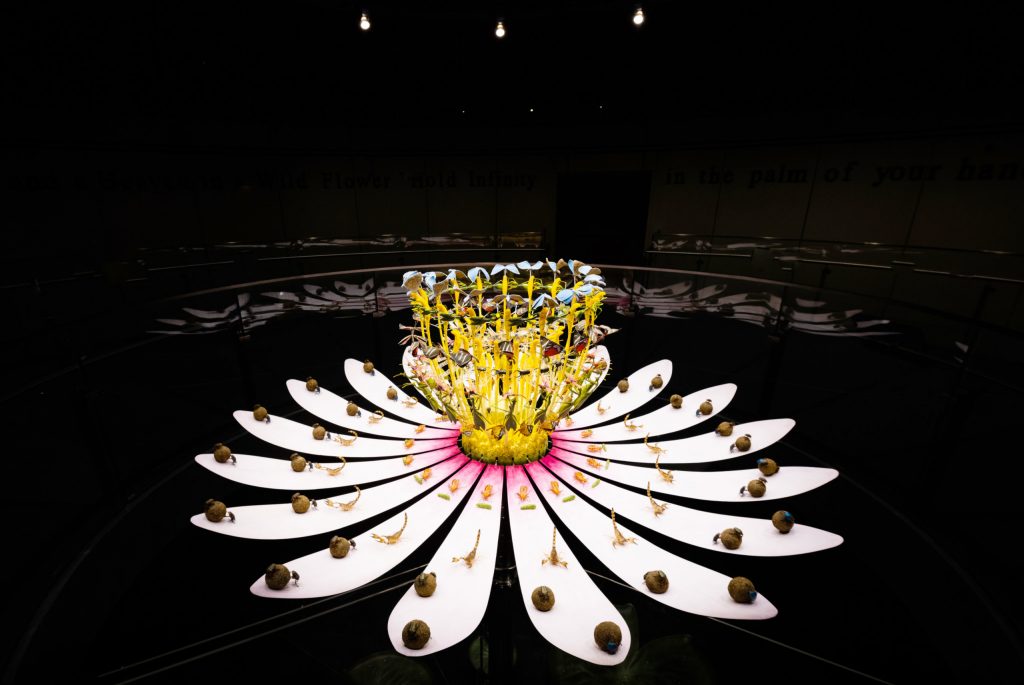

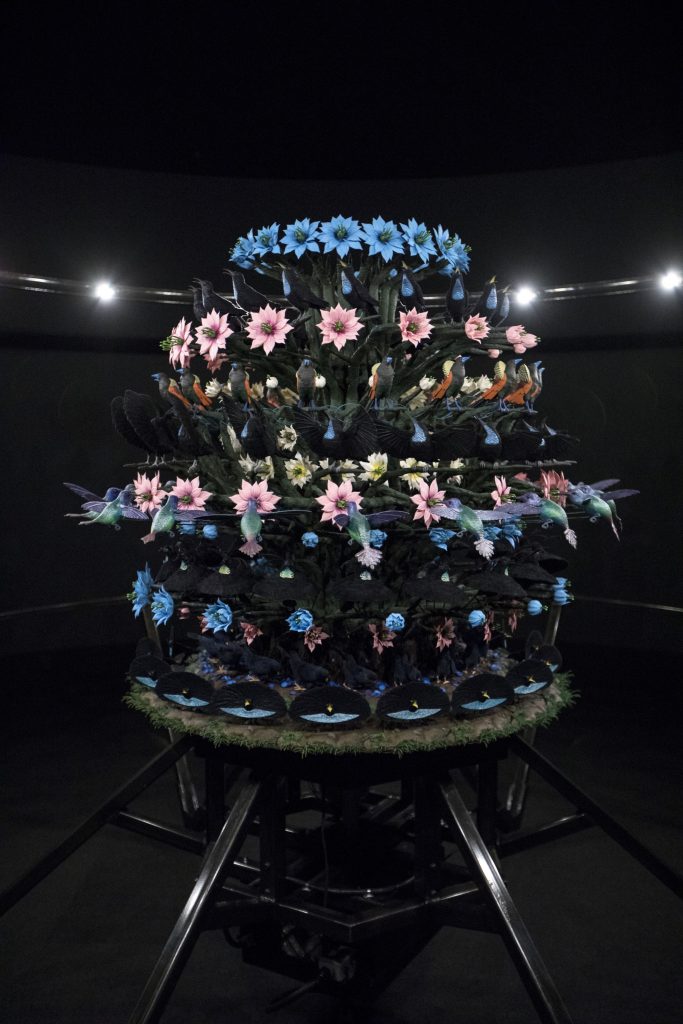

Mat Collishaw, Heterosis, Digital Collectibles, 2023. Courtesy of the Artist.

Still, I loved the idea that the sharing, buying, and selling of tulips formed a community and even served as a form of socializing. Collectors would show their latest collections, hybridize and nurture them, and then give or sell them to other people. It was a way of impressing their friends and their business acquaintances by demonstrating their sophistication, their ability to breed or identify a new flower or show off the wealth that allowed them to purchase this rare tulip. It seems like the most damaging result of this tulip crash of 1637 was that some people, understandably, didn’t want to pay the high price for the flowers that they’d agreed to in January or February after the prices crashed. This resulted in a breach of trust between collectors, which was dangerous for a whole network that depended on mutual trust between all parties. That is quite different from the situation today. With the blockchain and the way it treats transactions, this kind of breakdown of trust can’t really happen again.

This led me to think about the networks and the communities involved in contemporary NFT collections. Take the fact that those historic collectors and breeders were practicing a form of genetic engineering by creating rarer and rarer forms of tulips. They had a particular favorite flower: the most variegated, the ones with the most stripes, and the stripes that were most flamed and feathered. Tulips with these characteristics were most desirable; The rarer they were, the more valuable they were. The beauty of the flower was judged not only by its beauty but by its rarity, as well. Value and beauty are tied to rarity. All of these ideas are interesting fodder for an artist, but the most important fact is that all parties involved were circumventing evolution, which normally relies on natural selection.

Mat Collishaw, Heterosis, Digital Collectibles, 2023. Courtesy of the Artist.

I started thinking about ways to do that in the virtual world. Take flowers. First, you get a seed of a flower; it blossoms, and then you can potentially hybridize your flower with another flower to achieve certain properties of that other flower. Inevitably you begin to encounter recessive genes, revealing certain characteristics that you’re not aware of. Your flower may not appear to carry that gene, and the other pair of flowers don’t seem to have it, but it’s still there, and your flower could potentially inherit it. We took this basic idea and started working out other mechanics. For instance, when you use multiple breeding with your flower, you might discover an entirely new species of flower.

Afterward, you can set the price for other collectors to breed with your flower after you have developed your unique, rare example. All of these created flowers are based on real species like tulips, irises, water lilies, and passion flowers. In our art, the geometry and the shaders that we use are characteristics that you find in the world of botany. We also introduced several other traits, which I’ve used in my previous work: translucency, like a ghost flower and an ultraviolet flower, or a flower that has animal-like petals. These are special traits that people may or may not want but that broaden the spectrum of a flower’s appearance. Shaders and patterns are not the only things that can change geometry. The number of petals on your flower, the spikiness, the length of each petal, the curvature of each petal, the kind of floppiness of each petal—you can affect all of these by breeding your flower with another one.

Mat Collishaw, Heterosis, Digital Collectibles, 2023. Courtesy of the Artist.

AC: Will a larger audience get to see the outcome of the project, or will it be limited to buyers and investors?

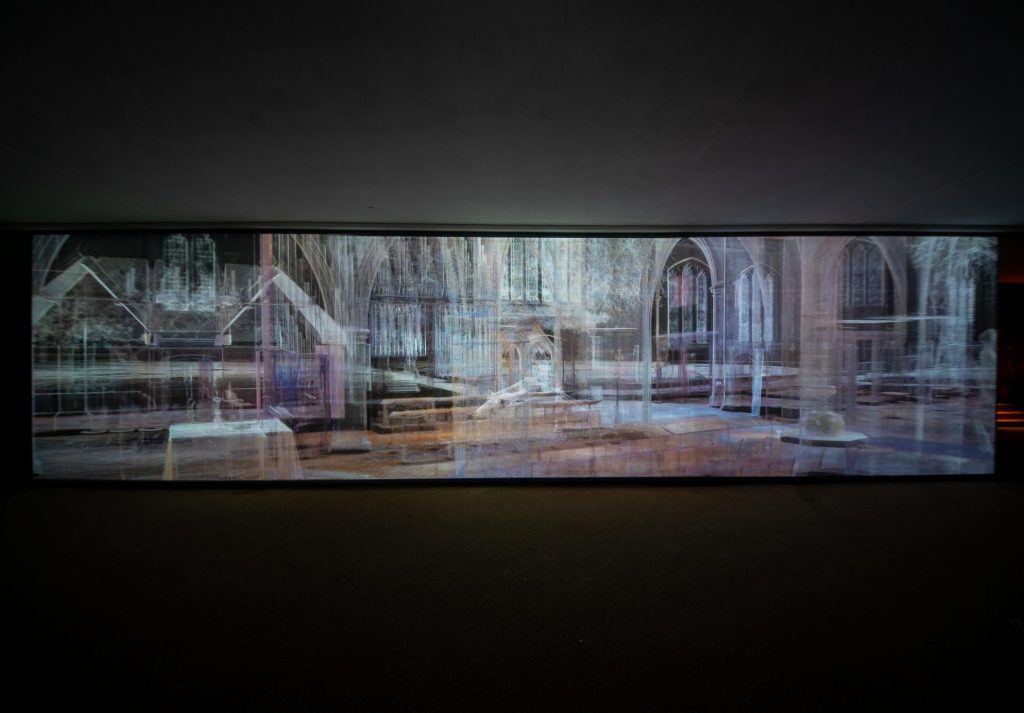

MC: We’re currently working on that. Obviously, the flowers are going to be visible on the OG.Art website. We’ve also been working on developing a persistent, immersive social space where you can enter a virtual room, navigate your way through it, and interact with various things, either using a VR headset, your phone, or a desktop computer. We want to create a persistent world, available 24/7. We have recreated room 32, the largest and most amazing room in London’s National Gallery, but as though it were neglected and abandoned. Nature has taken over. It’s as if some kind of post-apocalyptic scenario occurred, and nature has started to fight back.

Mat Collishaw, Heterosis, Digital Collectibles, 2023. Courtesy of the Artist.

All the flowers in the collection will appear in their current iteration inside this National Gallery room, to which all collectors will have access. They can log in with a browser link, and then they can adopt an avatar, navigate around, meet other people, talk with them, and see all the flowers. You can move closer to a particular flower, click on it, examine all of its properties, and see its current value in the marketplace. There will also be a link to this virtual world accessible to other people not involved in the project that allows them to enter this virtual world, experiencing whatever environment exists in London at that time. That means that if you log in from Chicago, it will be midnight in London, and you will see a moonlit scene with fireflies illuminating the space.

AC: When are you launching this project?

MC: We are hoping to launch at the beginning of March. We think the project should run for about three months, which should be long enough to explore the full extent of the project. We’re not really sure. We might extend it.

AC: As you mentioned, you’ve used this technology in several of your artworks. How has technology impacted your artistic process and the message that you would like to share with your audience?

MC: Massively. I use it in everything, but as you say, at the heart of it all, there’s got to be some kind of soulfulness. It’s got to be about one person communicating with other people. And that’s what’s special about making artwork. You can visit a gallery and see a sculpture, and through that sculpture, you can reflect, communicate, and have a connection: with the artist, with what it means to be alive and to be human, and to deal with the human condition. Hopefully, all those things are part of visiting and experiencing an artwork—and technology shouldn’t get in the way of that. For me, it’s just an amazing tool. I’ve used it in so many different areas, and I will continue to do so. But it’s always important to me that I humanize it. In doing so, I try to use historical ideas or art history in order to serve as the bridge between things that happened in the past and things that are happening now in the tech world.

Mat Collishaw, Equinox, 2021. Artist’s website.

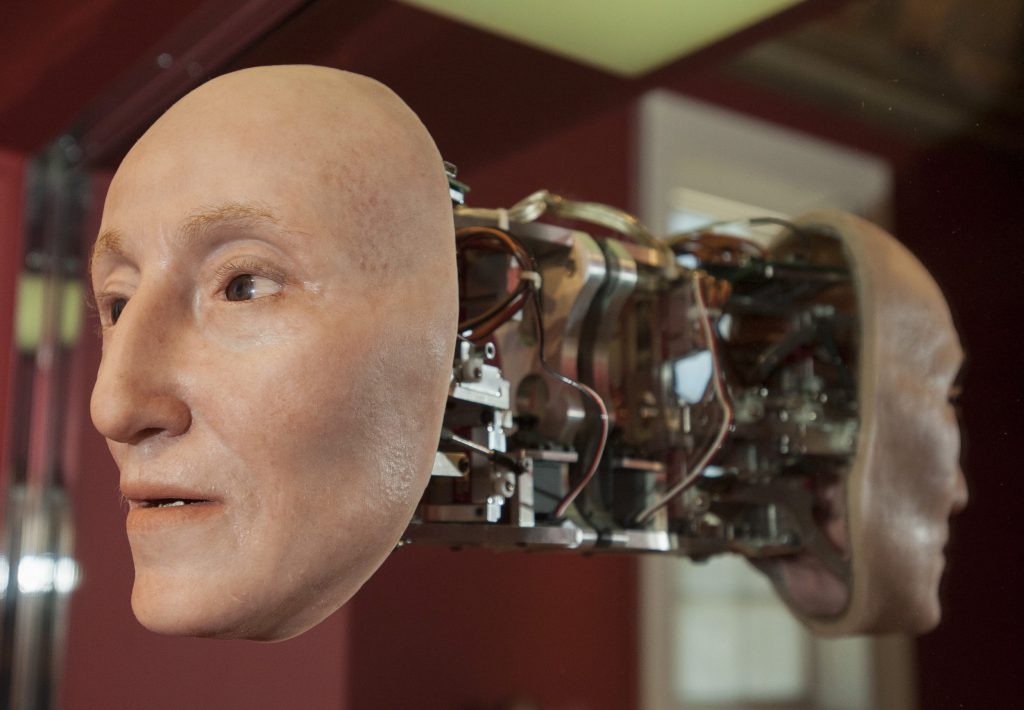

I did an exhibition in Dubai last year, and quite a few of the works in there were about the potentially harmful effects of technology. I’m making another work which I’m exhibiting in London in a couple of months. It’s about our addiction to these devices and the way that the software inside these devices was designed to capture our attention and lock us in. It explores effects like online abuse and trolling; taking people down and canceling them; the mob mentality; misinformation, disinformation, and deep fakes. All of these processes are very predatory; they are malign influences that we have to be aware of and be very careful of, particularly as a younger generation is growing up and knows nothing except communicating through these devices. I tried to make a lot of work about that, including an exhibition that recreated the experiments by B.F. Skinner where little pigeons in cages had to peck little buttons to get a reward.

Mat Collishaw, Echolocation, 2021. Artist’s website.

He described a principle that he called the variable reward when the birds became totally addicted to pecking. He introduced a mechanic where the bird would peck, but then the reward would come randomly, so they wouldn’t know when they would receive their reward. At that point, they became totally addicted to pecking, and this principle was adopted by designers of Facebook and Instagram just to keep us locked in. It’s just the unknown. So things like likes and comments and shares make us addicted and keep us coming back. I recreated these things as little animatronic machines, conditioned and programmed by unknown forces.

Mat Collishaw, Albion, 2017. Artist’s website.

AC: How do you see the future of art that involves more and more technology? I think the generations that come after us probably won’t be able to consume art without using technology. They’ll be so used to being online and consuming everything virtually.

MC: It’s a very scary world we’re moving into. I think the biggest problem with technology is polarization. It’s very important for an artist to engage with technology. Personally, I love going into a pretty much empty gallery space, seeing one sculpture in there, and having this church-like experience. You’re out of the real world, in this virtual world, and you have two or three minutes to respond and navigate around this piece of art and reflect, and afterward, you’re back in the real world. I love the solace of the intimate relationship you can have with physical artwork. I also think it’s very important to engage with technology and the way everything is moving so quickly, to be part of it, and to keep that artistic impulse within the new, burgeoning media while also making people aware of the potentially corruptive and malign effects of it. That’s what I’m trying to do. I don’t think AI-generated artwork or text will ever really take over because, ultimately, you want to experience something generated by another person who has had experiences like yours.

Mat Collishaw, Burning Flowers, 2014. Artist’s website.

All of these emotions, which are very particular to being human, and the experiences that other humans have, are something that I believe art is about. Art is a humanizing process. It becomes a forum in which our experience is mediated. I’ve been generating a lot of images and text using AI, but I use them as tools which I then moderate massively. I try to engage with them. I’m aware of the fact that they’re not really giving me what I want, and they’re nevertheless very interesting.

Take all of the titles for the flowers in the Heterosis collection. I wanted something that resonated with the whole way the project works. In the end, we took a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, “The Library of Babel.” It is a thought exercise in which you imagine an almost-infinite library filled with every book that’s ever been written—and every book that’s never been written.

However, if you try to find your own life story in this library, you’d spend your whole life looking for it. We took this short story and used it as a lexicon to generate all the titles for the artworks in Heterosis. All in all, I don’t really know where we’re going or what we’re going to do, but I think it’s important to engage in trying to make this new tech meaningful.

Mat Collishaw, Centrifugal Soul, 2016. Artist’s website.

AC: Where do you find inspiration for your work? How does it all start?

MC: I make a lot of notes. Afterward, it’s a process of finding other ideas that tie into the initial one. If I’ve got one idea, it’s probably not that interesting; if I have several ideas and several threads, then I can draw them together, making the work layered in some way. That’s when it gets interesting for me. I tend to read quite a wide range of books and articles, from botany to philosophy and the history of human struggle. For me, it’s a process of reaching out in multiple directions and then saying, “Well, this thing here could be linked with that thing there.”

As we think of virtual reality, we can see that the beginnings of photography were very similar. It was part of the Industrial Revolution, and things were changing very quickly everywhere. Everything was becoming mechanized. This had social repercussions: people were losing their jobs. When the photograph was first exhibited in 1839, it was shown at an exhibition of cutting-edge science and technology, alongside all the latest machines and innovations taking jobs away from people who were outside on the street, demonstrating against unemployment and disenfranchisement. They didn’t have any rights in the political process to decide what was happening with factories. We are now seeing the same thing with virtual reality and artificial intelligence. We are going through a new digital revolution, and just like before, there will be social repercussions.

Mat Collishaw, Centrifugal Soul, 2016. Artist’s website.

AC: So when you have the concept, how do you take it from there? And how long does it take to create your artwork?

MC: I work totally alone, but I’ve worked with many different people on different projects. As I’ve worked with engineers for several years, I’ll start talking to my project partners pretty early on. Obviously, there are certain parameters; there are certain technical limitations to what we can do. So as the idea evolves, we have to say, okay, well, this is probably not going to work. This is too heavy, and I want it to move too quickly. So how do we amend it effectively? There’ll be other people that I work with, like animators, so I’ll share an idea with them pretty early on, and then I’ll make a rough sketch, they’ll send something back, and then I’ll say, let’s change it a little bit. The project will generally evolve with the experts, people who can actually do things in the world, unlike me. And we try to bring the project together. And normally, it’s about like a year or 18 months of evolution from the first ideas coming together to the actual thing being finished.

Mat Collishaw, The Mask of Youth, 2018. Artist’s website.

AC: What’s your personal message with Heterosis? What do you want to give people with this project?

MC: It’s the first time I’ve really worked on such a collaborative project. I’ve never really appreciated this. The idea of people coming together and collaborating almost at random doesn’t interest me. I’m much more interested in the voice of a single artist, and that one person’s vision is what I’d like to share. It’s a solitary meeting of two minds. So why collaborate? However, in these artworks, given the subject matter—the community of Dutch flower breeders and collectors suddenly changing the course of the tulip’s evolution—I found collaboration very interesting.

They all had a hand in the collective appearance and identity of the tulip flower. Using that as a model for me is quite special and mysterious. I think art should have some sense of mystery in it, even if it’s only the mystery of evoking something deep in our subconsciousness so that when we experience it, we don’t really know why we’re attracted or engaged. It’s tapping into something that’s quite primal. This is what I’d like to do in my work. This mysterious, organic, semi-organic process is bound to happen as collectors hopefully choose to breed their flowers.

For the first nine months of production for Heterosis, Danil Krivoruchko (co-creator of the Heterosis project) was generating flowers. Every week, we got new tulips or new orchids. A couple of weeks ago, we let the algorithms generate flowers randomly for the first time to see if everything was working. It was so weird and mysterious and beautiful to see these things flourishing seemingly out of nowhere. What happens within this community when collectors take one flower and breed it with another flower is a very mysterious phenomenon, and I’m genuinely interested in seeing how it evolves. More than that, though, I’m trying to make a project that couldn’t exist in any other environment. It is dependent on this community. The fact that it all exists online on OG.Art, and the ability to access it within a centralized space. Where does beauty lie? Where does the value lie? How is it affected by rarity? All of these things are very interesting questions to deal with. This is a total artwork with many different threads inside it.

Mat Collishaw, The Venal Muse, 2012. Artist’s website.

AC: I think that with technology, the outcome can even be surprising for the artist themself. I also wonder whether beauty or rarity is more important for people with NFTs.

MC: Tulip collecting in the 17th century established that beauty is dependent on rarity. When the market gets involved, this is what happens. Rarity is the key indicator, and that’s going to be part of this experiment. People will have an idea of beauty, but if it’s not rare, then is it really going to be of less value than something that is weird and ugly but rare?