Between Word and Image: The Creative Mind of David Jones

David Jones (1895–1974) was an artist, poet, writer and craftsman; a name synonymous with the Modernist era but one that still remains lesser known...

Guest Profile 21 October 2024

James Sidney Edouard, known as James Ensor, was a Belgian painter and printmaker best known for his colorful compositions, imbued with both autobiographical and social themes. Born in 1860 in the seaside city of Ostend, Ensor was one of the most prominent members of the Belgian Realist movement and an important influence on the development of Expressionism. Here we explore his oeuvre in 10 paintings.

James Ensor, Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat, 1883, Mu.ZEE, Ostend, Belgium. Kiama Art Gallery.

In this early traditional portrait, Ensor depicts himself as both confident and assertive as he locks eyes with the viewer. The portrait reflects Ensor’s formal academic training, having just finished his studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels (1877-1880). The dark background sets a serious tone, while the colorful plumage and flowers emanating from his soft white hat add a playful touch. It is the perfect introduction to an artist who would spend a lifetime producing eccentric paintings that were at once both whimsical and bizarre.

James Ensor, The Oyster Eater, 1882, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, Antwerp. Wikipedia.

In The Oyster Eater from 1883, a young lady enjoys a meal at a table laden with glassware, linens, and flowers. The scene is set in Ensor’s childhood home, where the artist lived and worked for much of his life. The woman is his sister, Mariëtte Caroline Emma, whom he affectionately called Mitche. This painting is one of a series of small-town scenes by Ensor, which he painted using a light color palette and loose brushwork in an Impressionist style. The choice of subject matter— a lonely woman eating what was considered to be an aphrodisiac— was not well received. When the Antwerp Salon of 1882 rejected this painting, Ensor took swift action and established his own avant-garde group, Les XX.

James Ensor, Tribulations of St. Anthony, 1887, MoMA. Wikipedia.

A notable shift in color palette and abstraction can be seen in this painting from 1887. The story of the temptation faced by Saint Anthony of Egypt during his sojourn in the desert has been widely revisited throughout the history of art. Ensor takes the religious theme of the saint’s fight with the Devil and other demons and imbues it with a sense of the bizarre. His colors are intrepid and his brushstrokes erratic. Ensor gives the familiar story his own spin, following in the footsteps of past Flemish masters Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) and Pieter Bruegel (1525-1569), who also rendered this subject. Ensor’s painting, with its disarray and blasts of color, gives us a glimpse of what lies ahead.

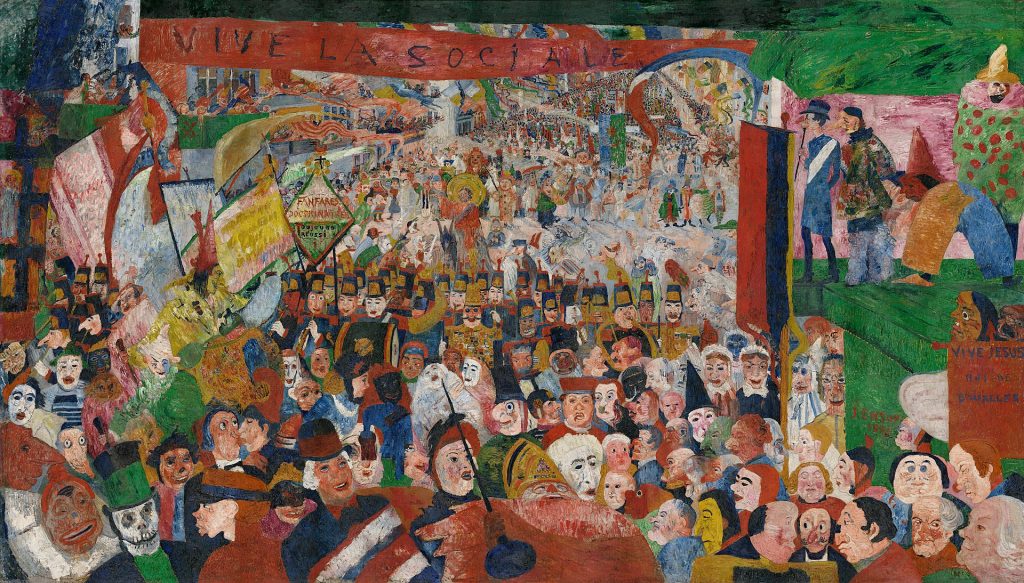

James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Wikipedia.

This monumental painting from 1888 is considered Ensor’s most famous work and a forerunner of Expressionism. Measuring 2.53 meters in height by 4.31 meters in width, it is so large that Ensor had to work on it in segments, nailing one part of the linen canvas to the wall at a time. Ensor lays on thick paint to depict a brightly-colored procession welcoming Christ into the contemporary Belgian capital. Ensor’s tiny Christ is engulfed in a cacophony of grotesque clowns, caricatures, and Belgian politicians, suggesting a parody of modern society. The artist reminds us that we live in a world governed by absurdity.

Many autobiographical elements make their way into the work as well. Most notable is the fact that the scene takes place during the annual carnival in Brussels, instead of the Biblical entry into Jerusalem, along with the colorful masks. Ensor grew up in his family’s souvenir shop in Ostend where masks and other trinkets were sold. The mask motif would become central to Ensor’s oeuvre and also a recurring theme in the majority of his works.

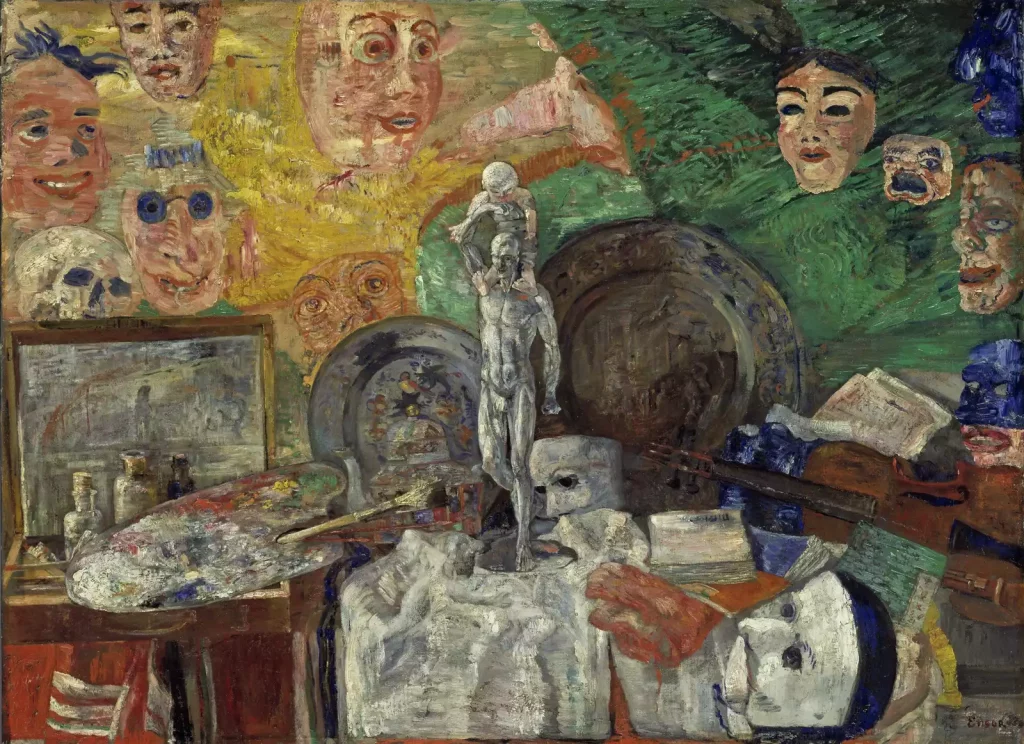

James Ensor, Still Life in the Studio, 1889, Bavarian State Paintings Collection. Artsy.

Ensor produced a number of still lifes throughout his career. His Still Life in the Studio features a disorderly mélange of masks and other objects, including a statuette of a man with a child on his shoulders, decorative dishes, a violin, and the artist’s paint tubes and colorful palette. His use of white paint produces an almost reflective surface on the objects in the foreground, particularly reminiscent of the tablescape in his Oyster Eaters.

However, Ensor’s assortment of expressive and grotesque masks creates an unsettling mood. Perched atop a framed painting is a skull, a memento mori alluding to the ephemerality of life. Ensor’s studio was in the attic of his parent’s home, just steps away from the North Sea. After his death, his home was preserved in its original state and made into a museum. The James Ensor House can still be visited in Ostend today.

James Ensor, The Intrigue, 1890, Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp. Royal Academy.

The Intrigue features a group of masked figures set against a light blue sky with streaks of white clouds. Autobiographical in nature, the scene was inspired by an episode that took place in the artist’s hometown. The central figure wearing a green cloak with blue hair is Ensor’s sister, Mitche. She links arms with her fiancé, a Chinese art dealer from Berlin, who wears a towering black top hat and a black scarf furled around his neck. Their controversial engagement caused outrage in the town of Ostend. This is Ensor’s critical depiction of the townspeople, mocking, laughing, and pointing at the couple, all while conveniently hiding their true identities behind their masks. The event would haunt the artist for much of his life.

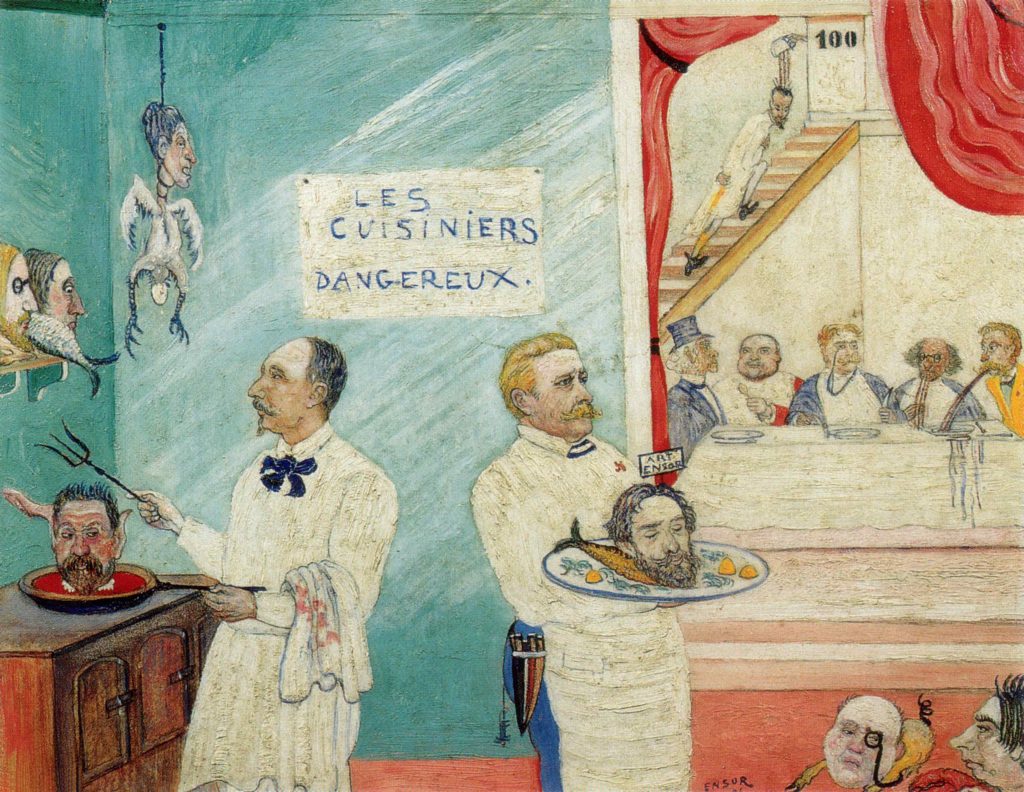

James Ensor, The Dangerous Cooks, 1896, private collection. Spike World.

Unlike the last few paintings we’ve analyzed, The Dangerous Cooks does not feature masks or carnivals. Rather, the work is a highly satirical response to the artist’s personal plight with the disintegration of his group, Les XX. At the center of the composition, a head is served on a platter, flanked by a fish and other gastronomical adornments—it is the head of Ensor himself. Serving Ensor’s head is Octave Maus, one of the founding members of Les XX. The two had recently had a number of disagreements. The image of Ensor’s lifeless head recalls the recurring theme in art of Salome with the head of St. John on a plate. Whether or not he intended to liken himself to a martyr, it is clear that Ensor’s works became increasingly satirical and grotesque through the years.

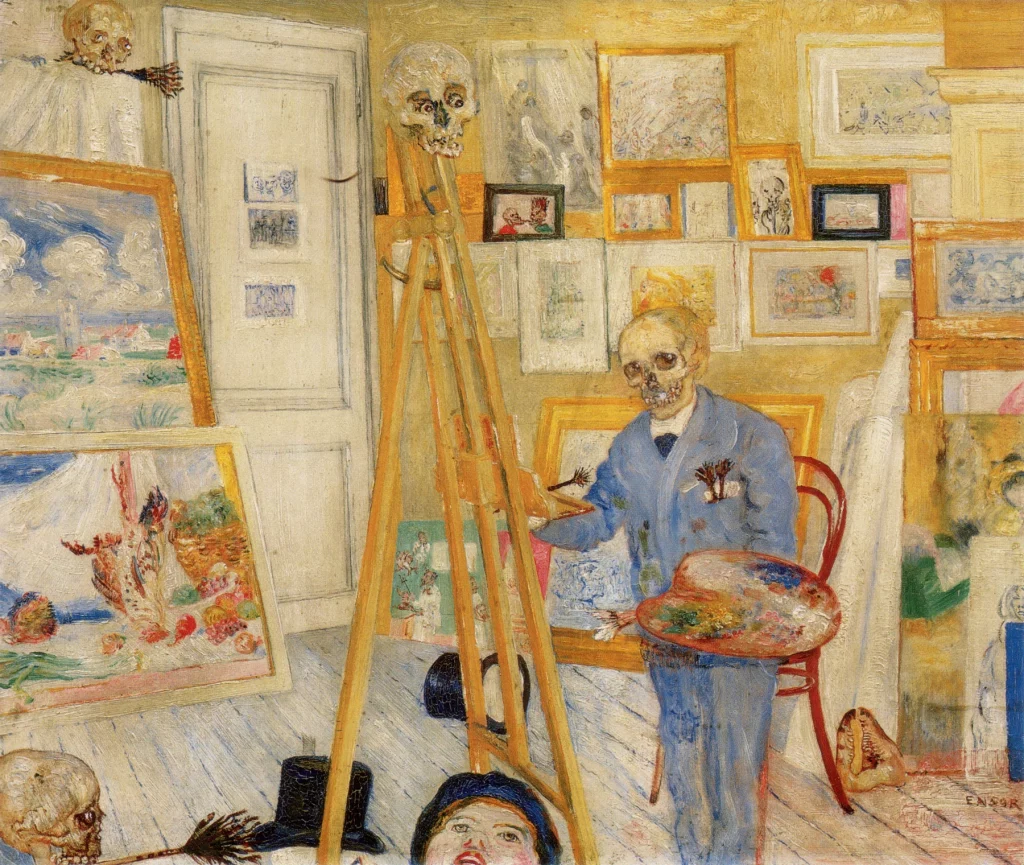

James Ensor, The Skeleton Painter, 1896, oil on panel, Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp. Obelisk Art History.

In the same year, Ensor created The Skeleton Painter. Here, we see the artist standing at his easel in the attic studio of his family home. In the place of his head is a skull, implying the mortality of the artist. Two more skulls make an appearance, one perched atop the artist’s easel and the other sitting upon a draped painting. The large canvas on the left-hand side of the compositions features a landscape with the church of Mariakerke, where the artist would eventually be buried. Towards the center of the composition, just above the artist, sits a small black frame with one of Ensor’s most famous paintings, Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring. A few masks also make their way into the composition. They lie on the floor, useless, as if to imply that they no longer serve a purpose after death.

James Ensor, The Great Judge, 1898. WikiArt (public domain).

The theme of death is part and parcel of Ensor’s oeuvre at the turn of the century. In The Great Judge, we see a familiar arrangement of figures that calls to mind that of The Intrigue. Yet here a skull takes center stage, and the masks appear dormant. Even the sky is grey and lifeless. Perhaps all the chatter and gossip weren’t worthwhile after all. Ensor reminds us that we are all on a finite journey, leaving us with another memento mori that recalls the inevitability of death.

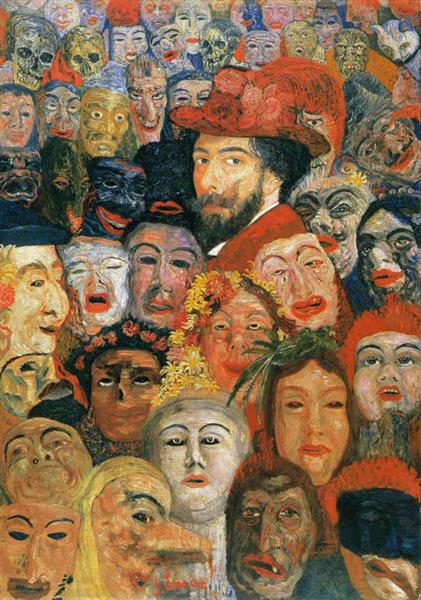

James Ensor, Self-Portrait with Masks, 1899, Menard Art Museum, Komaki, Japan. WikiArt (public domain).

In Self-Portrait with Masks Ensor depicts himself amidst a colorful sea of carnival masks. He is the only unmasked figure and is featured front and center. When we lock eyes with him, we realize that he is the same man as in his initial Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat. He wears the same hat with the same downward-facing plumage, only this time in red. Is he telling us that he is an artist who never managed to fit in? Or that he is the only sane one among a throng of fools? Ensor put it best when he said:

I have happily confined myself to the land of mockery where everything is a brilliant but violent masquerade.

Diane Lesko. James Ensor: The Creative Years, p.4.

James Ensor died in 1949 in the same seaside Belgian town where he lived and worked for the majority of his life.

Diane Lesko. James Ensor: The Creative Years. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!