Masterpiece Story: Wheatfield with Cypresses by Vincent van Gogh

Wheatfield with Cypresses expresses the emotional intensity that has become the trademark of Vincent van Gogh’s signature style. Let’s delve...

James W Singer 17 November 2024

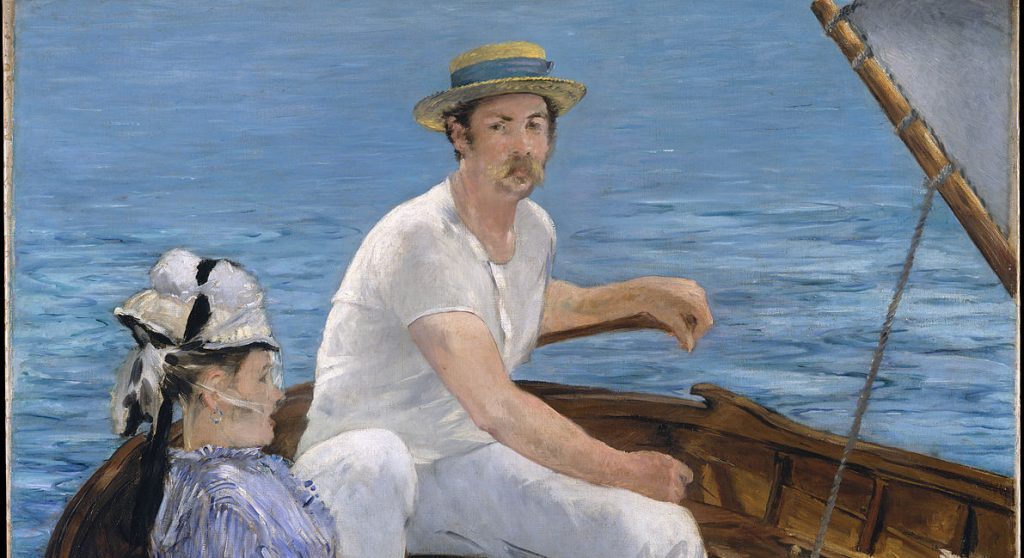

Known as the father of modernism in art, Édouard Manet was a key figure in the shift from Realism to Impressionism. Finding the guidelines of the French Academy of Arts far too rigid, he preferred to capture modern and unconventional scenes of everyday life. While Manet resisted joining the Impressionists, his works reveal an intimate interplay with the groundbreaking art movement. Here we dive into Manet’s masterpiece from 1874, Boating.

Édouard Manet was among the first artists to paint modern life in the 19th century. While much of his work reflects Impressionist ideals, Manet never joined the pioneering group, choosing instead to submit his works to the Salon, the official art exhibition of the French Academy. However, Manet’s relationship with the Salon was turbulent as he often pushed back against the rigid guidelines of the Academy. Manet defied traditional techniques and preferred to paint modern life. This gave him a prominent place in the famous 1863 Salon des Refusés, which showcased works rejected by the official jury.

In the Summer of 1874, Manet left the bustling city life of Paris for the tranquility of Gennevilliers, a northwest suburb of the French capital. Manet’s family home was just across the Seine from Argenteuil where Claude Monet lived at the time. The two artists visited each other regularly and worked alongside one another en plein air, “in the open air”. Argenteuil was a popular boating resort among wealthy Parisians for weekend getaways, and thus a prime location for people watching.

Édouard Manet, Boating, 1874, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA. WikiArt .

In Manet’s Boating we can almost hear the ripples of water gently rocking the boat to and fro in the warm summer breeze. Manet paints a luminous image imbued with brilliantly contrasting hues of deep aquamarine, rich brown, and crisp white. Compared to much of his earlier work, here Manet experiments with a lighter color palette and open brushwork. The influence of his Impressionist comrades is indisputable in this portrayal of la vie moderne.

The painting depicts a man believed to be Rodolphe Leenhoff, Manet’s brother-in-law, and a woman whose identity is uncertain. Manet manages to capture the interiority of the subjects, particularly the man, who locks eyes with us with his arresting gaze. The body language of the sitters suggests a level of comfort, which, in turn, makes us, the viewers, feel as though we have just interrupted a private moment. Is the woman aware of our presence? Are we, too, on the boat? Or have we been caught in an act of voyeurism?

Édouard Manet, Boating, 1874, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA. World History Encyclopedia. Detail.

The couple takes part in a popular leisure activity among the French Bourgeoisie. The man is at the helm with his arm resting on the boat’s oar. He is dressed in all white and wears a yellow straw boater hat with a blue stripe. This suggests an affiliation with the exclusive French boating club, the Cercle Nautique.

The short, quick brushstrokes typical of Impressionism are particularly visible in the woman’s attire. Her fashionable clothing is a symbol of her status and modernity. She wears an elegant belted striped dress and a tall hat with a veil designed to keep water and dust out of the eyes. The black ribbon tying down her hat mimics the rope fastened to the boat’s sail in the upper-right corner.

Édouard Manet, Boating, 1874, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA. World History Encyclopedia. Detail.

At the end of the 19th century, Japanese Ukiyo-e images, or “pictures of the floating world,” were in vogue among the Impressionists. In fact, many components featured in these Japanese woodblock prints made their way into the Impressionists’ depictions of modern life.

Boating is perhaps the painting by Manet that most closely embodies the spirit of Japanese woodblocks. Like in many Ukiyo-e prints, our vantage point is from above and positioned at a slight angle. Pared down to its basic elements, Manet’s scene lacks a horizon line, revealing nothing but boundless water. A sliver of the sail and only a portion of the boat are included in the composition, with the rest of the vessel outside of our line of vision. Manet’s asymmetrical perspective, contrasting colors, and fashionably dressed woman in a nautical setting all recall Japanese prints. The bold diagonal lines in Manet’s Boating are reminiscent of Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Girl Feeding Ducks, from which the artist may have drawn inspiration.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Girl Feeding Ducks, left sheet of the triptych Water: A Drifting Boat, 1851, color woodcut on Japan paper, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Museum’s website.

Manet’s Boating was shown five years later at the Salon of 1879 where it did not go unnoticed. The artist’s Impressionist tendencies were promptly pointed out in contrast to the traditional portraits and historical paintings accepted by the Royal Academy. While the blue water was considered too bright and unreal by many, the positive reception of the artwork reflects that the history of art was on the cusp of an important transition. One critic, Joris-Karl Huysmans, wrote:

The bright blue water continues to exasperate a number of people… the woman, dressed in blue, seated in a boat cut off by the frame as in certain Japanese prints, is well-placed, in broad daylight, and her figure energetically stands out against the oarsman dressed in white, against the vivid blue of the water. These are, indeed, pictures the likes of which, alas, we shall rarely find in this tedious Salon.

Indeed, the psychological depth and daring style of Boating make this alluring snapshot of modern life anything but tedious. Manet’s creative edge and fresh ideas inspired a new generation of artists and subsequently laid the foundations of modern art.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!