Summary

- History of the movement and its development

- Influences

- Surrealist art beyond France

- Surrealist techniques

- Movement’s legacy

The Man Who Defined Surrealism

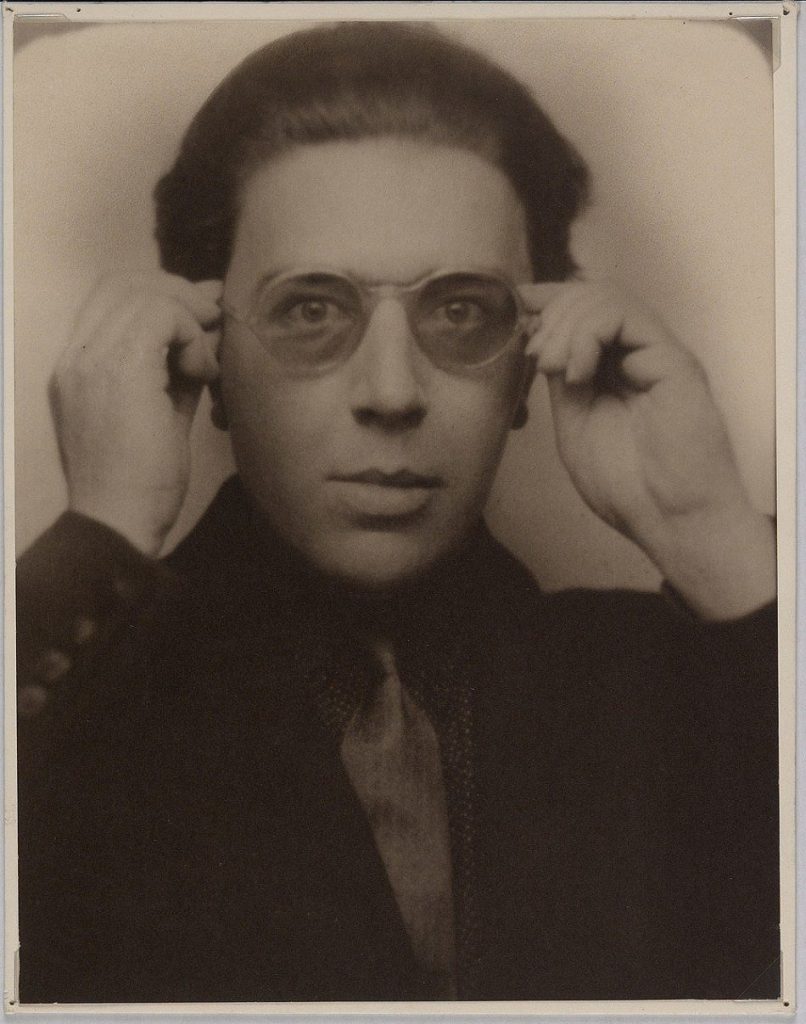

In 1924, the surrealist movement’s founding manifesto was published. French poet and author André Breton is the author of this inaugural essay. According to him, surrealism is pure psychic automatism-a definition illustrated using the automatic writing method based on the spontaneous association of ideas. In other words, the goal is to express thoughts without rational restraints. The process of creativity includes randomness, and Surrealists claimed it can generate beauty. It becomes possible for the unconscious and conscience to reconcile themselves.

The manifesto, which was influenced by Freud’s discoveries about the unconscious mind, outlines the movement’s guiding ideas. Imagination can be sparked by investigating the unconscious, asserting the omnipotence of the dream. André Breton invites us to see surrealism as an artistic process and to experiment with it in daily life. The dream does not exist to escape reality, but to improve it. Surrealism transforms our way of thinking; it says within a disenchanted world, it is an effort to pay attention to the hidden wonder, to focus on the marvelous.

A new revolution has begun. For Breton, a number of writers from his day have come to represent it: Paul Eluard, Philippe Soupault, Louis Aragon, Robert Desnos, etc. The manifesto is also an opportunity to put them forth.

André Breton, Portrait d’André Breton aux lunettes, 1924. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

While André Breton was a passionate promoter of art and invested in the artists that he designated as surrealists, he used all means to reach his goals, including encyclopedias, manifestos, reviews, exhibitions, scandals, and polemics. This is also the first time in history an art critic has established himself as the head of an avant-garde movement; you can’t get around the so-called “pope of surrealism (his adversaries gave him this nickname in order to criticize the absurd drifts of this position).”

By flirting with dogmatism, the manifesto draws the boundaries of surrealism. This method of operating led to numerous disagreements and rifts with other surrealists; they held opposing viewpoints or merely desired to maintain their independence. However, this theoretical doctrine also enabled the movement to be organized and become a structured strategy for action. This undoubtedly contributed to its enormous popularity.

Influences

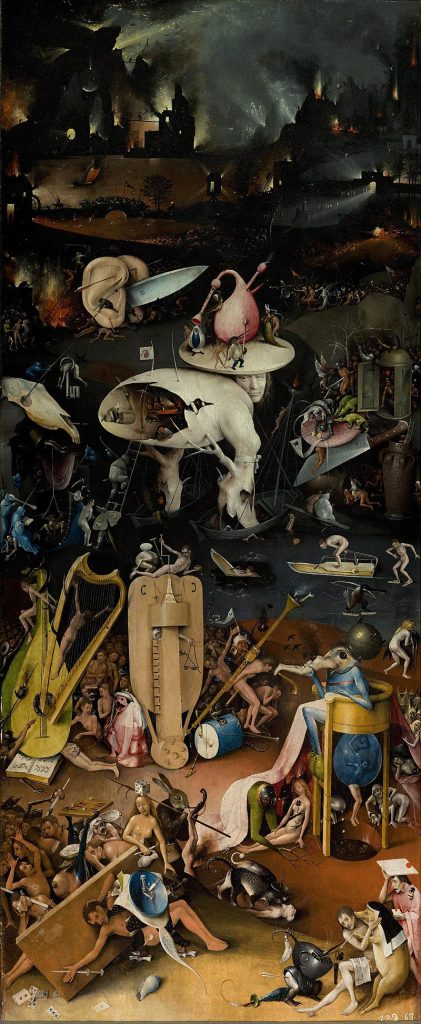

The founder of Surrealism also looked back and identified many ancestors, including the textual hallucinations of Arthur Rimbaud and the Count of Lautréamont, Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland and her dreamlike adventures, Giorgio De Chirico’s metaphysical paintings, Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s vegetable characters, and Jerome Bosch’s intriguing works. André Breton aimed to demonstrate that Surrealism was part of a tradition as a way to legitimize this movement within the history of art.

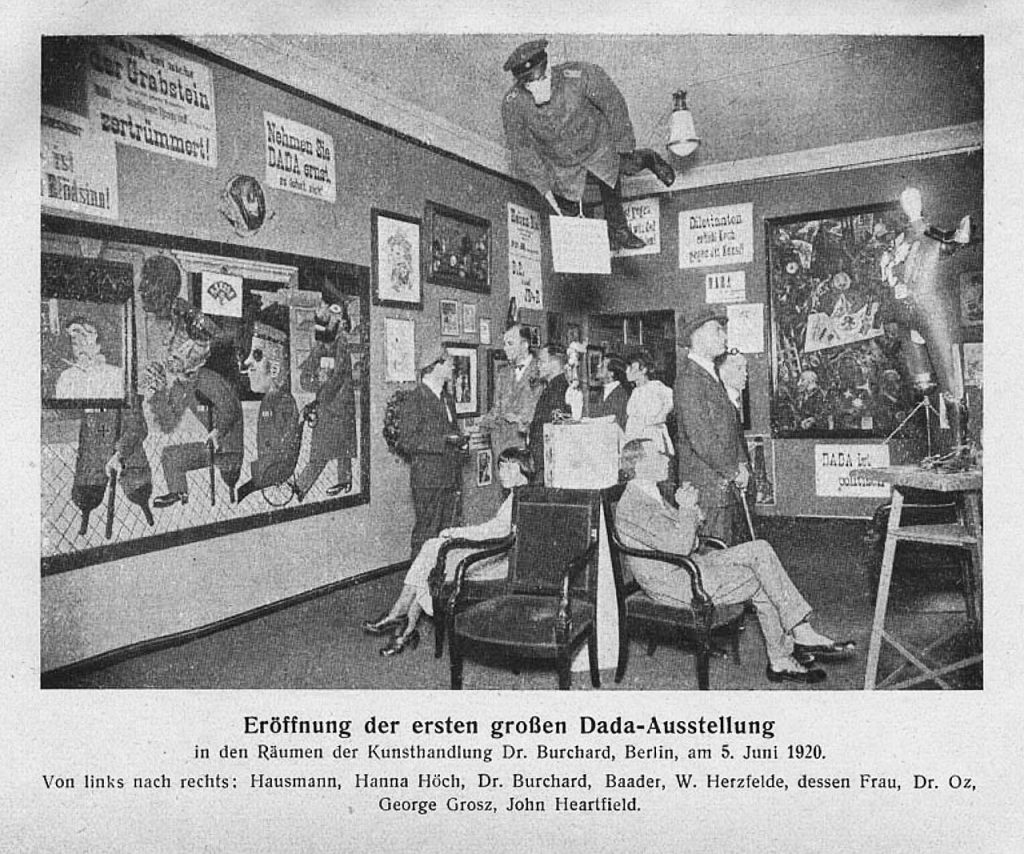

Surrealism’s primary influence, however, is far more recent: it was the Dada movement. During the first world war, young artists like Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp gathered to express their rage against society. They opposed the anarchy and the illogical reasoning that caused the chaos of their time and claimed to break with what preceded. Their approach is made of provocation, satire, and irony and they fostered an appreciation for the absurd. They were anti-military, anti-religion, anti-bourgeois, even anti-museum. They were anti-everything.

André Breton had a soft spot for Dada. It is evident that this movement gave birth to Surrealism thanks to its radical approach to erasing boundaries. But Dada’s nihilistic attitude also stood in the way of the quest for the marvelous. It was against the future-focused ideas that drove the surrealism revolution, for Surrealism carried the potential to reimagine humanity. As a result, the break with Dada was inevitable; the principles of Surrealism forced Breton to liberate himself from the movement.

Grand opening of the first Dada exhibition: International Dada Fair, Berlin, 1920,

Surrealism Is Everywhere

Originally, Surrealism was a French literary movement, particularly in poetry. However, its principles quickly found resonance in the visual arts and spread internationally.

The list of major artists who have been associated with Surrealism at some point in their careers is impressive: Man Ray, Max Ernst, Joan Mirò, Yves Tanguy, Luis Buñuel, Dora Maar, Salvador Dali, Méret Oppenheim, Alberto Giacometti, Roberto Matta, Claude Cahun, Paul Delvaux, etc.

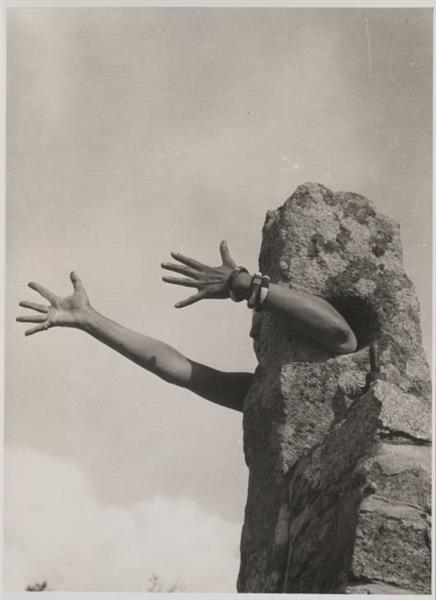

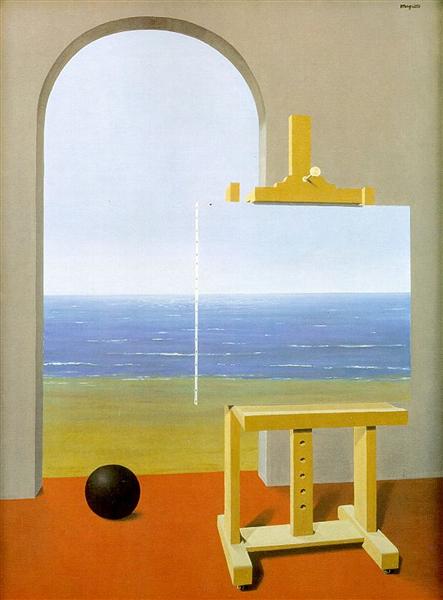

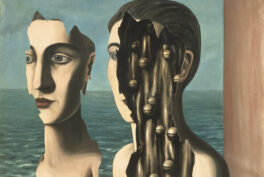

Artists in many countries appropriated Surrealism and proposed relevant works, even in opposition to André Breton. For example, automatic writing was one of the principles with which the Belgians disagreed with Breton, and was reflected in the school of Brussels’ one-of-a-kind works: Raoul Ubac’s and Paul Nougé’s photography, E.L.T. Mesens’ collages, and René Magritte’s iconic paintings. Magritte’s paintings are not based on chance, but are the result of careful planning and reflection, which does not prevent you from experiencing surreality while watching his works. Magritte’s form of surrealism is distinguished by a reflected play between the represented elements, the links that unite (or do not unite) them, and the language.

Surrealism entices people from all over the world. Many countries formed groups, including Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Sweden, England, Romania, Egypt, and Japan. This international creative emulation produced powerful works–consider the works of Dorothea Tanning, Remedios Varo, Ramses Younan, or Toyen.

Exhibitions & Publications

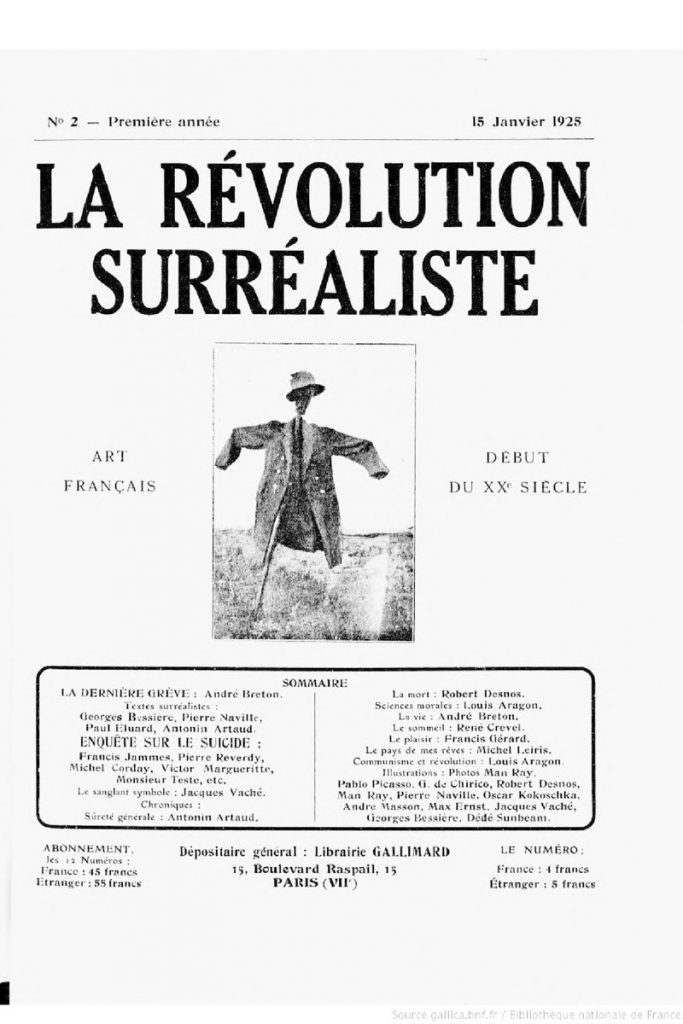

The numerous exhibitions and publications centered on Surrealism contribute to this international expansion. La révolution surréaliste was the most famous and influential magazine, though there were others, such as Minotaure in Paris and View in the United States. These media were crucial in spreading surrealist ideas in artistic and intellectual circles.

Cover of the second issue of La Révolution surréaliste, 1926. Wikipedia.

Significant Surrealist exhibitions were held in Brussels, Paris, Copenhagen, London, New York, and Tokyo, increasing the movement’s visibility. It became a source of inspiration for many artists, which explains why various surrealist groups sprang up all over the world. Breton attended numerous exhibitions to show his support and to identify new recruits.

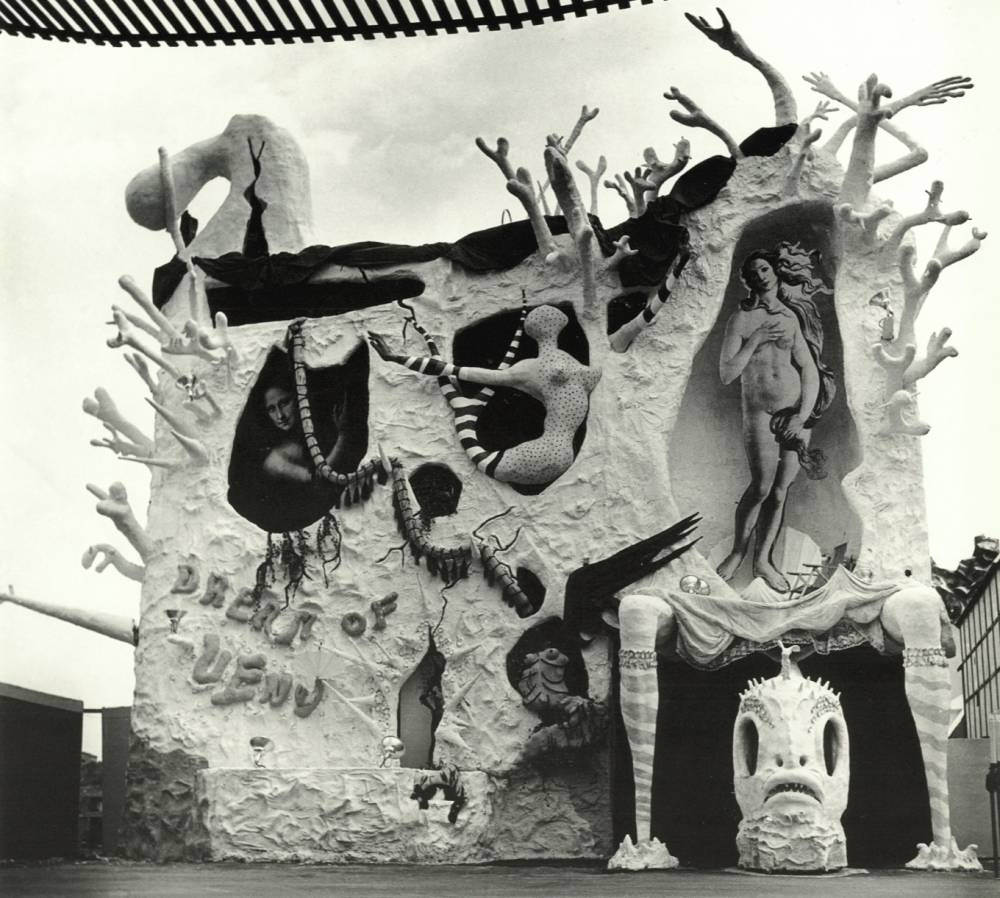

These exhibitions have received considerable attention. The art they proposed was appealing, but the surrealist innovation goes even further: the exhibitions were holistic and immersive. The visitor’s senses were called upon and visitors could play within a journey-like experience. For example, at the International Exhibition of Surrealism in Paris in 1938, the public was given flashlights to examine the works’ details. They could also hear recorded sounds and smell odors among the works. This was also the beginning of installations as an art form; consider Dali’s pavilion Dream of Venus at the New York International Fair in 1939, a delirium of architecture that transports the viewer to an underwater world populated by female figures.

These multidisciplinary exhibitions were appealing due to their innovative creativity and the majority of them achieved public success. They contributed significantly to the popularization of Surrealism and the development of more immersive curatorial projects.

Salvador Dali, Dream of Venus pavilion, 1939. Minniemuse.

Surrealistic Tricks

To reveal the marvelous, to allow the unconscious to speak outside the control of reason, and to provoke chance, the artists employed a variety of processes, many of which were new in the history of art. Here are 5 tricks used by the surrealists.

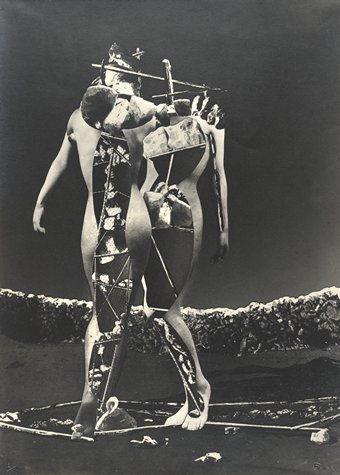

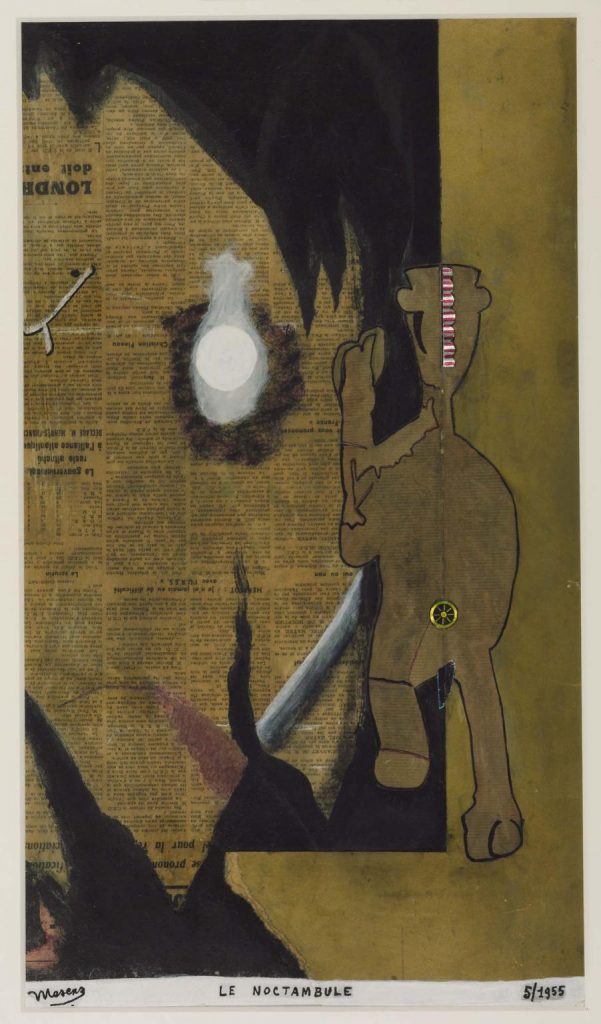

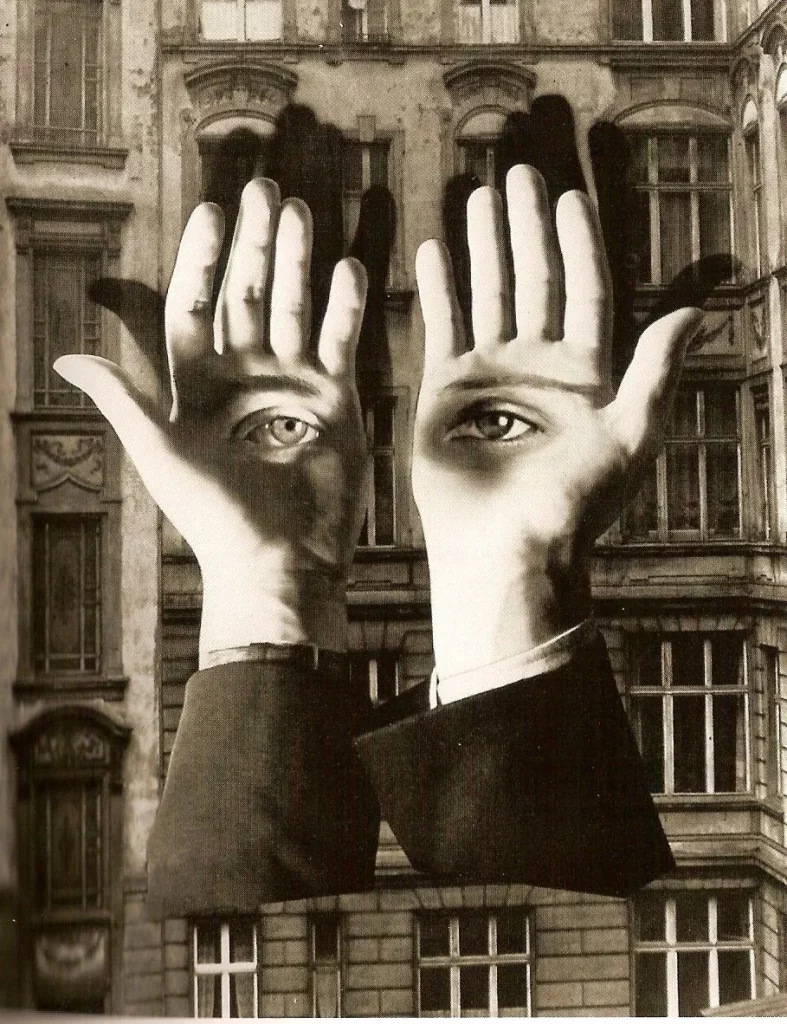

Collage

Collage is a fundamental surrealist technique. It is based on the juxtaposition of images from various sources, such as books, newspapers, and reproductions of works of art. Collage allows you to connect elements that have no prior relationship; the goal is to evoke unusual encounters and to reveal a new meaning. Surrealist collages introduced new visual associations; it used dream language to express a poetic universe.

Surrealist objects are, in some ways, three-dimensional collages. The juxtaposed elements are found objects and cheap materials in this case, but the principle is the same as it is on paper: to create an incongruous mystery.

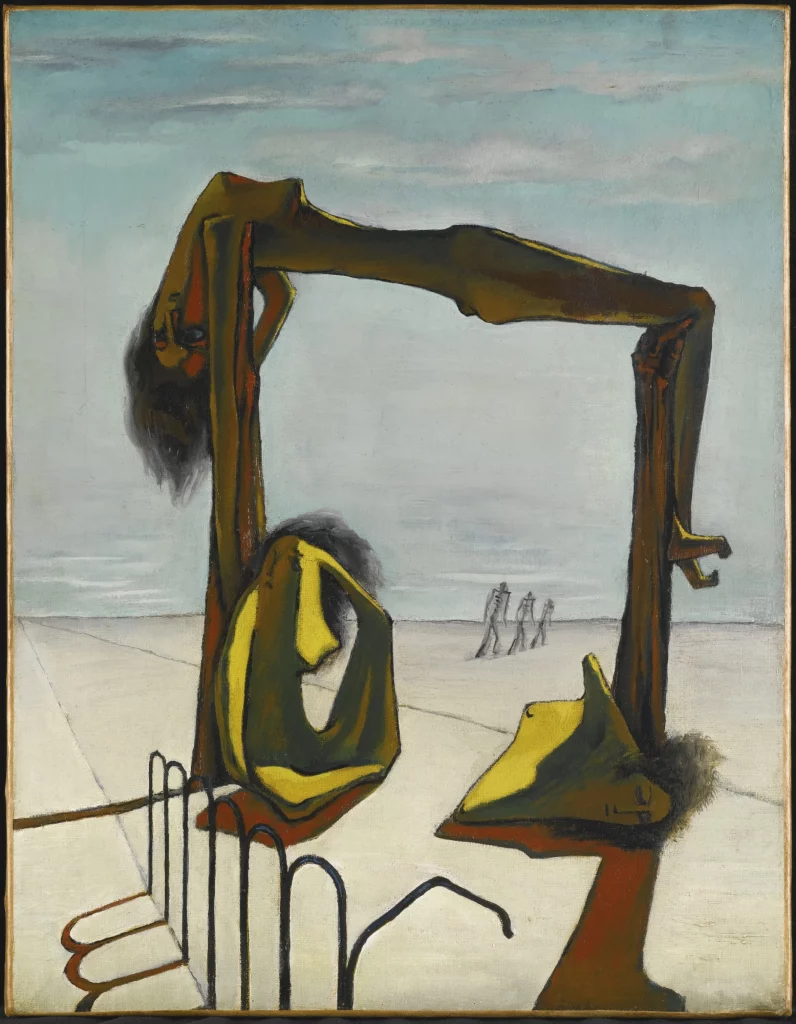

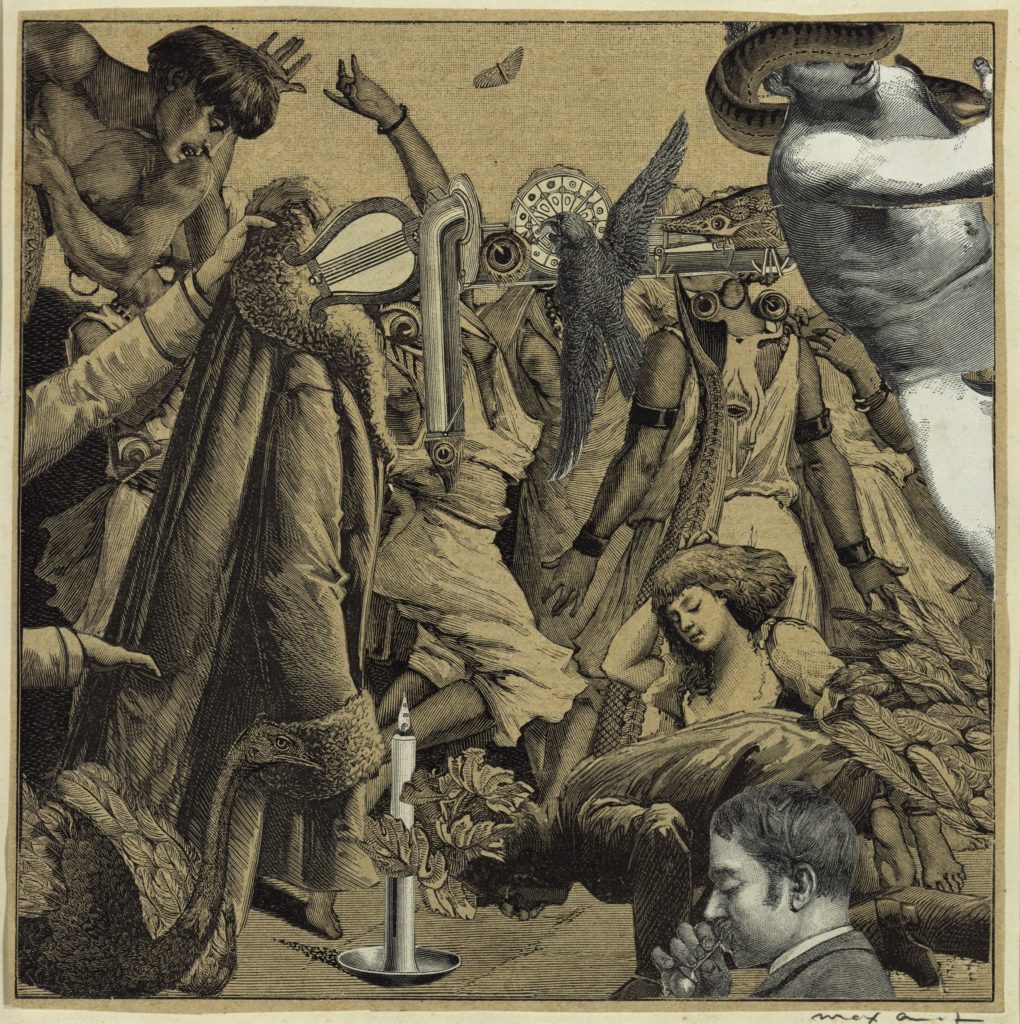

Rubbing

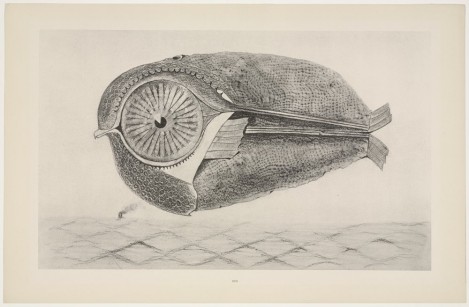

The pictorial equivalent of automatic writing is rubbing. Max Ernst was the one who discovered it. It started out as a floor imprint; he would rub a piece of paper on the floor with a pencil. Then, he applied this technique to other textures.

Max Ernst, The fugitive, 1926, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

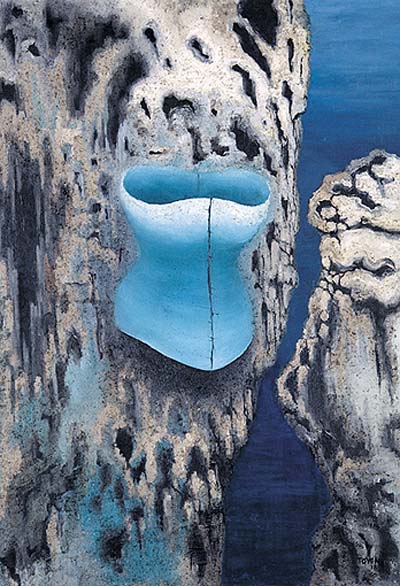

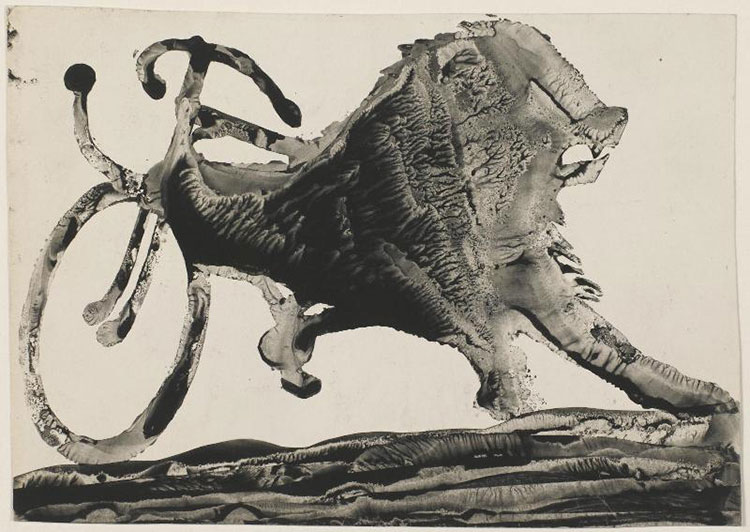

Decalcomania

Óscar Dominguez was the first to employ decals in a creative context. The technique is straightforward: the artist presses a white sheet of paper onto another sheet of black gouache-coated paper and repeats the process until the image appears satisfactory. The result creates forms and landscapes with an intriguing allure, which are always unpredictable.

Óscar Dominguez, Lion-Bicycle, 1937, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

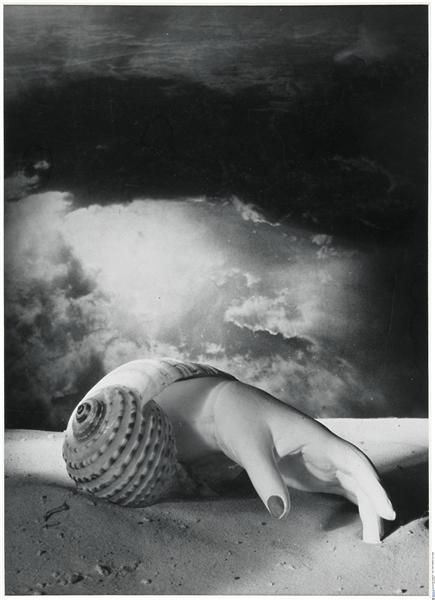

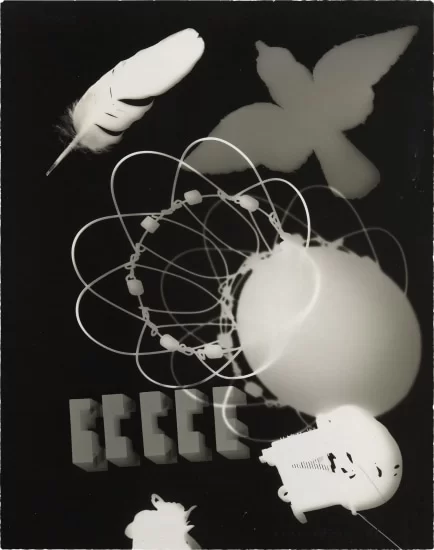

Rayography

Photography is also a technique evoking chance. One of the most famous surrealist photography techniques is the rayograph, named for the artist Man Ray who discovered the technique by accident- he left an object on photographic paper, which he then exposed to light (without using a camera). Surprisingly, the final result was incredibly aesthetically-pleasing and Man Ray’s rayographs were a huge success.

Man Ray, Untitled, rayograph, 1946, Phillips, New York, NY, USA.

Solarization

Lee Miller discovered this technique while working with Man Ray. She unintentionally revealed a negative she was working on, and this produced an almost inverted black-and-white image with a slight aura surrounding the subject. A diaphanous oddness; so surrealistic. Lee Miller, by the way, went into photojournalism after her surrealist phase and covered the Second World War.

Lee Miller, Solarized portrait of an unknown model, 1930. Wikiart.

Legacy

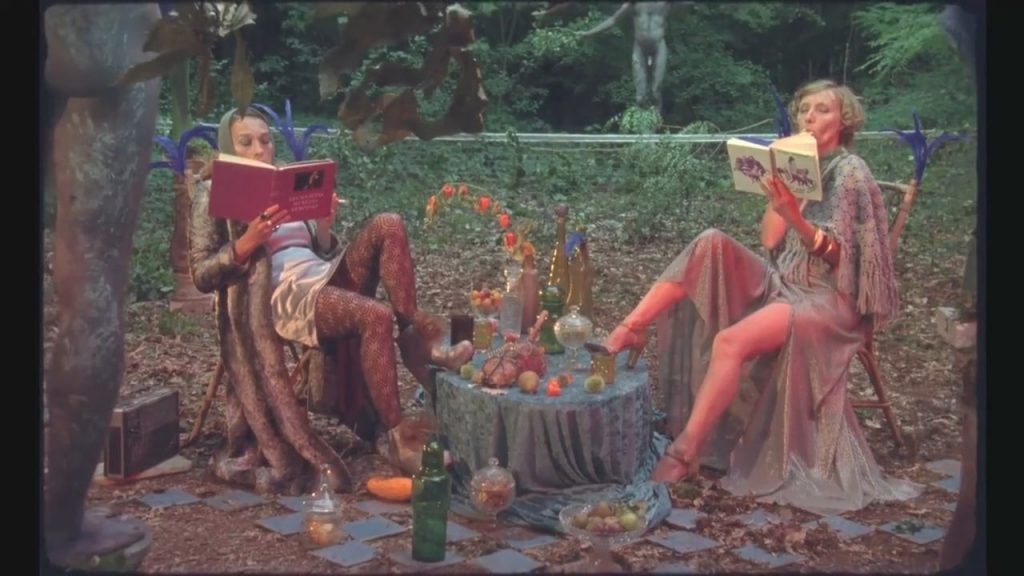

Surrealism has left its mark on art history. Many works have emerged in its wake: Beat Generation writings (Allen Ginsberg’s free association poems or William Burroughs’ cut-up technique), Jackson Pollock‘s spontaneous drippings, the beginnings of Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Louise Nevelson, the regressive joy of the CoBrA movement, the new realists (particularly Niki de Saint-Phalle), and even Pop Art and hyperrealism started with Magritte and Dali. Isn’t it the surrealist imprint that we see in filmmakers like David Lynch or Bertrand Mandico?

Movie still from Our lady of hormones, directed by Bertrand Mandico, 2014. Unifrance.

Surrealism celebrates the imagination. It was a breath of fresh air after the devastation of World War I, a place where changing human nature appeared to be possible once more. It provided hope, but history has shown that it was only a temporary truce; the worst was yet to come. However, the surrealist quest for the marvelous has survived, most likely because humanity carries it within ourselves and maybe that is where the hope is. This is what makes this artistic movement so appealing nearly a century after its founding.

Want to know more about Surrealism? We highly recommend you read Surrealism by Dr Amy Dempsey. Do you want to know more but don’t have enough time to read a book? Watch this video. For the French speakers, here is an interview with André Breton himself.

We have purposefully mixed male and female artists in this article, however this should not blind us to the period’s misogyny, which did not spare this movement. Fortunately, the work of female artists during this period is becoming more and more visible. Want to know more about this topic? We recommend the book Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement by Whitney Chadwick and Dawn Ades.

Surrealism also had a complex relationship with the political tendencies of its time, which we did not address in this article. If you are interested in more about that topic, we recommend you read this article.