Berthe Morisot

“Given your daughters’ natural gifts, it will not be petty drawing-room talents that my instruction will achieve; they will become painters. Are you fully aware of what that means? It will be revolutionary—I would almost say catastrophic.”1 In 1857, Joseph Guichard warned Madame Morisot that if her talented daughters continued to paint, it would prove a disastrous affair. Berthe Morisot and her sister, Edma, had shown a strong interest in art from a young age and, thanks to their nurturing parents, studied painting under some of the finest instructors of their day. But while Edma would soon abandon her paintbrush to focus on her role as wife and mother, Berthe would go on to revolutionize modern art.

At a time when women were confined to a life of domesticity, Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) pushed societal boundaries and defied convention. She achieved professional success, establishing herself as a career woman, as well as a wife and mother. The only female founder of the Impressionist movement, Morisot represented a disruption in the upper milieu of Parisian society and in the history of art at large.

Known for her intimate interior scenes and introspective portraits of female sitters, Morisot painted what she had access to in her everyday life as a bourgeois woman living in 19th-century France. She didn’t have a studio, so she painted in her living room and bedroom. She couldn’t frequent the late-night cafes and cabarets, so she painted outdoors or in private spaces. Nevertheless, she took part in all the Impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886, apart from one, which was held just months after giving birth to her daughter, Julie. Morisot worked alongside the most prolific—and rebellious—artists of her day, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, and was a key figure in the movement that broke away from the École des Beaux-Arts and its rigid guidelines.

The Exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery

Entering the gallery, visitors are greeted by Morisot’s commanding presence and confident gaze in her celebrated self-portrait, painted in 1885 when she was 44 years old. Morisot wears what appears to be the red ribbon of the légion d’honneur, France’s highest order of merit, awarded by the French state to male artists. In this painting, Morisot comes down off the museum wall and assumes the weight of a pioneering woman artist.

But as we make our way through the first gallery room, we quickly discover that this retrospective explores a new angle of the female Impressionist—that is, the ways in which Morisot engaged with 18th-century art. Hanging alongside the majority of her works on the gallery walls are paintings by the male forerunners who are said to have informed Morisot’s artistic output. We soon learn that Morisot’s formative years coincided with the rediscovery of French 18th-century art. While a much-appreciated fact, we find our eyes brushing past these names—Fragonard, Gainsborough, Reynolds, Romney—in search of the name of names—Berthe Morisot. As we proceed through the gallery rooms, we are on an intrepid hunt for works painted by the hand of the female Impressionist.

Morisot’s Light-filled World

As we enter her world of women, we witness how Morisot so brilliantly captures the transitory. Tender interior scenes unveil moments of quiet reflection and ephemeral joys. Morisot’s rapid zigzags and distinctive white brushwork draw us into her paintings. Her canvases are brimming with warm tones and pastel hues. One art critic noted how Morisot painted with a “palette of crushed flower petals.”2

This exhibition features a handful of Morisot’s most treasured works, including Summer’s Day (1879), Lady at her Toilette (1875-1880), The Psyche Mirror (1876), and Young Woman Watering a Shrub (1883), with her beloved daughter, Julie, making frequent appearances.

Her experiments with red chalk are a delightful surprise. Young Woman Reclining (1887) features preparatory gridlines, giving us a glimpse into Morisot’s artistic process. We learn that she was inspired by this popular 18th-century technique. Another unexpected treat is a pastoral scene by Berthe’s sister, Edma. Landscape, from the 1860s, allows us to relive the onset of the Morisot sisters’ artistic bond and the influence of their teacher, landscape artist Camille Corot.

By the third room, we come face-to-face with Morisot’s later works—some strikingly modern. Two Nymphs from Apollo Revealing his Divinity to the Shepherdess Issé (1892) is a direct homage to François Boucher’s grand 18th-century mythological tableau. Morisot’s decision to focus on the nymph duo, as opposed to the greater assembly of figures, reflects her continued effort to capture intimate moments and tiny pleasures. Telling more by showing less. It becomes clear that Morisot’s brushwork takes on a new life by the end of her career. Quick, short dashes become elongated, dizzying lines. It is as if, with the passing of time, her works become less immediate, less spontaneous.

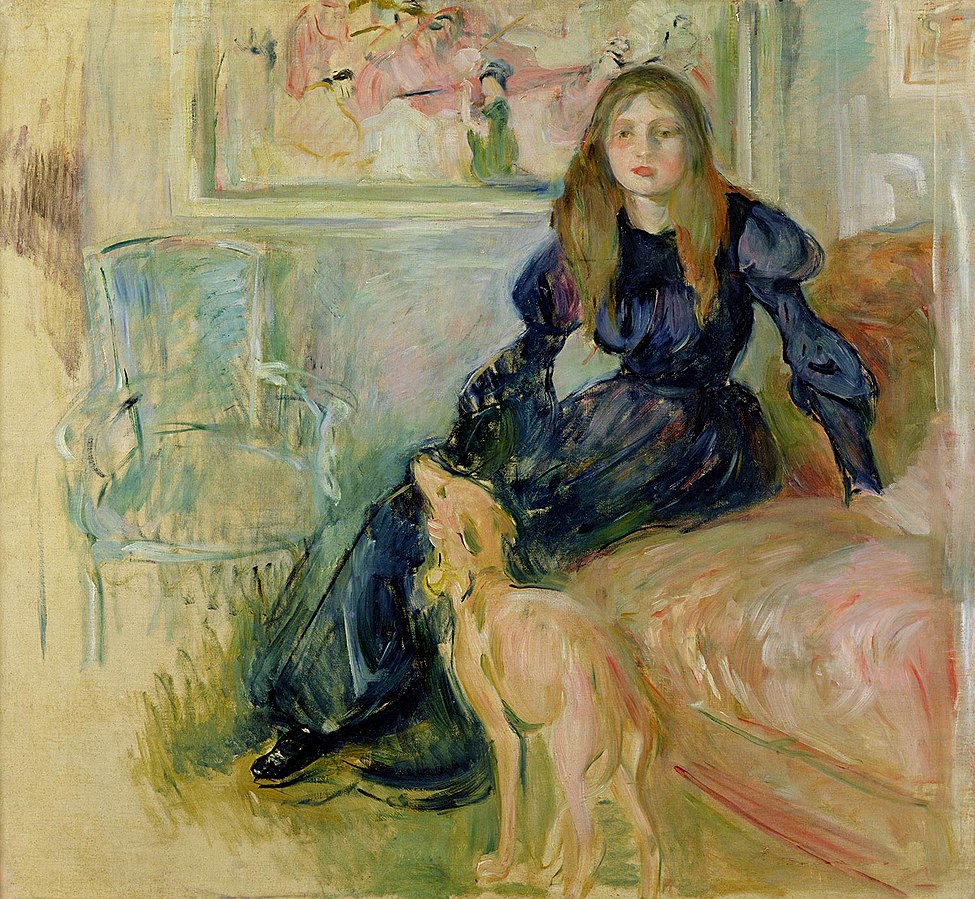

The exhibition concludes with a portrait of Morisot’s daughter, now a young woman, accompanied by her dog, Laertes. Characterized by a sense of longing, Julie is dressed in black, a symbol of her grieving state following her father’s untimely death. The painting prefigures the forthcoming death of Morisot herself, who would die two years later, after contracting pneumonia. The exhibition closes on a somber—albeit strangely hopeful—note.

Her Rightful Place in History

As an artist who has been overlooked for centuries, and who is still struggling to claim her rightful place in history, Morisot deserves her own unequivocal chance to shine. Morisot produced an impressive 860 paintings in her lifetime—something we would be surprised to learn after visiting this exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery. By placing Morisot within the parameters of male art history, the exhibition risks presenting a reductive concept of the sole female founder of Impressionism. The female gaze? We are offered it and denied it at once. While the contextual paintings are meant to remind us that Impressionism was in constant dialogue with previous centuries, their presence could be interpreted as undermining Morisot’s innovative contribution to the history of art. Despite the many noteworthy comparisons hanging alongside her works, we walk away armed with the knowledge that Morisot’s artistic oeuvre can—and should—stand alone.

Additional Information

Exhibition Dates: March 31 – September 10, 2023

Hours: Tuesday – Sunday, 10am – 5pm

Tickets: To book and for more information visit dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk