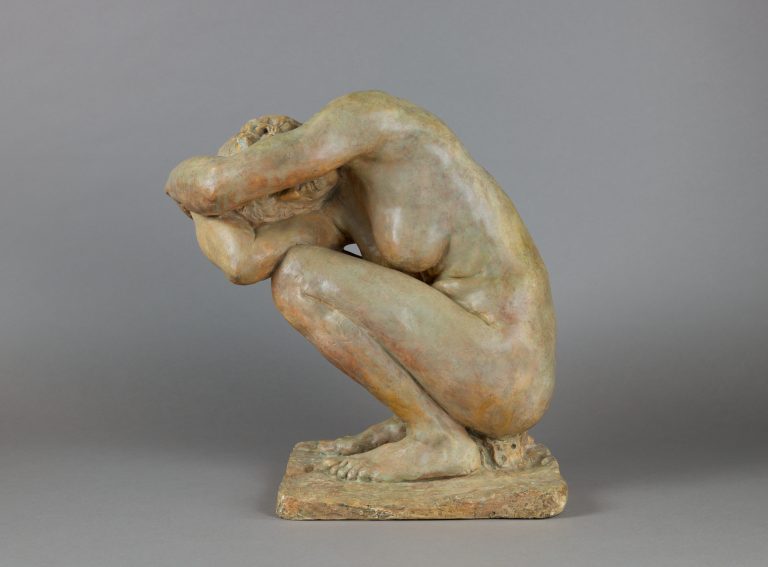

Showcasing a broad range of genres, formats, and materials in which Claudel worked, the pieces presented in this exhibition contended with universal themes of love, loss, passion, and the intimacy of daily experience. I had the pleasure of interviewing Emerson Bowyer, Searle Curator of European Painting & Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago, to discuss Claudel’s life, the physicality of sculpting, and his hopes for the exhibition, which was open from October 7, 2023, through February 19, 2024.

Natalia Iacobelli: Camille Claudel is almost always discussed in the shadow of her teacher, Auguste Rodin. What kind of artist was Claudel in her own right? Are there examples of works by Claudel in this exhibition that are uniquely her own?

Emerson Bowyer: Claudel was an enormously talented artist, who began sculpting as a teenager. For much of her short career, she sought to separate her work from Rodin’s in the public eye. A group of sculptures, known as “sketches from nature,” which she began in 1893, firmly established her unique style. These scenes from daily life, often depicting the activities of women, struck many critics as unprecedented, due to their lack of grand allegorical, historical, or mythological themes; the figures’ distinctly unclassical poses and features, and the miniature scale. One critic exclaimed: “By taking the ordinary parts of life and instilling them with art and plasticity, Mademoiselle Claudel has created a new art; she has struck gold. A gold that is hers alone.”

NI: This exhibition offered a rare opportunity to enter the world of Camille Claudel in the United States. In fact, fewer than ten works by Claudel can be found in American museums. Why do you think that is?

EB: Claudel’s career was much shorter than Rodin’s and she was not as prolific of a sculptor, nor was she patronized by collectors as frequently as Rodin. He forged close relationships with wealthy American collectors after 1900, and they devoured his sculptures, hence the vast number of lifetime casts by the artist in the United States. Claudel was mostly forgotten until the 1980s, after which, many of her best-known works were acquired by French museums. U.S. museums are working to address the gender imbalance in many collections–including works by Claudel. However, her sculptures are relatively rare on the market, fetching increasingly high prices at auction. After searching for five years last year, the Art Institute of Chicago was fortunate to acquire a newly discovered and unique plaster bust of Claudel’s brother, Paul.

NI: Claudel forged her way into the male-dominated arena of sculpture at the turn of the century. Can you talk a bit about why sculpture was deemed a masculine discipline?

EB: Unlike drawing and painting, which were increasingly seen as viable career paths for women, sculpture remained very firmly a masculine endeavor. It was considered too physical and necessarily relied on study of the nude body, which was frowned upon for women. Claudel was an exceptional carver of marble (which is particularly remarkable when considering Rodin didn’t carve any of his marbles himself). However, she frequently noted the toll such carving took on her physical health, which often pushed her to exhaustion.

NI: Much of Claudel’s oeuvre was produced in the first half of her life. Had she continued sculpting until her final days, what do you think she could have accomplished?

EB: Claudel was enormously creative and experimental. She was always trying to push beyond the limits of her medium: working with difficult stones like onyx marble and creating sweeping diagonals in compositions that threaten to tip over. Given this audacity, I’m certain that she would have gone on to produce exceptionally daring and innovative work.

NI: In bringing together nearly 60 of her artworks, did you gain a deeper understanding of Camille Claudel and her process? Is there something in particular you learned?

EB: I’ve learned many things about Claudel’s process, particularly while we’ve been installing the exhibition, and had an opportunity to compare sculptures that aren’t often seen together, as well as closely examining their undersides and surface details. She was very careful with her bronze casts, and we’ve been especially excited by the way in which she appears to have reworked their surfaces even after casting.

NI: What knowledge do you hope visitors of this exhibition walk away with?

EB: I hope that visitors will discover the fearlessness of the artist, admire her relentless pursuit of professional and social independence, and lose themselves in the beauty and emotion of her sculptures.