Summary

This article considers the story of Lili Elbe and Gerda Wegener through their art by considering:

- the complex dynamics and evolution of masculinity and femininity in Lili Elbe’s works

- the evolution and distinctive femininity in Gerda Wegener’s works

- the impact of Gerda Wegener’s art on Lili Elbe’s transition

- how their relationship is represented within their art

In fact, it was Alan Lucille Hart who underwent the first gender-affirming surgery in 1917. However, due to the publicity that both Lili Elbe and Gerda Wegener received during their time as public figures and artists, it was Elbe’s story and the couple’s relationship that established the relevance of their transgender experiences within public discourses. The lasting publicity and social impact were further reinforced by Lili Elbe’s autobiography Fra mand til kvinde: Lili Elbe’s bekendelser (From Man to Woman: Lili Elbe’s Confession) which was published in Denmark in 1931 and centers both her experiences of daily life and her transition process in detail. Most recently, their story was portrayed in the movie The Danish Girl (2015) which was based on the fictional book of the same name by David Ebershoff. This article considers Lili Elbe and Gerda Wegener through their art as both were exceptional artists first and foremost.1

Lili Elbe

Early Works

Lili Elbe’s early works consist primarily of wide-angle landscape paintings. During this time, landscape painting was considered a masculine discipline. The historically masculine connotations within Lili Elbe’ early works are further underlined by her artistic choices such as the wide-angle perspective, and the exclusive depiction of untouched natural landscapes, which were both considered distinctively masculine artistic choices within the Danish artistic context of the time.

Furthermore, in her autobiography, she describes her process of painting in a manner that would have been understood as particularly masculine in her time. This includes, for instance, her emphasis on her frantic, nearly violent process of creation and her close identification with birdwatchers and naturalists while painting, which were considered exclusively male professions at the time. Poplars Along Hobro Fiord is a prime example from her early works. A wide-angle depiction of a natural landscape with only marginal human influences with predominant dark greens and browns.

Lili Elbe, Poplars Along Hobro Fiord, 1908, private collection. WikiArt.

The painting shares recurring elements found in many of Lili Elbe’s works. These include the central theme of fluidity, often represented by water, present in nearly all her paintings. Another common feature is the inclusion of a small bridge, which carries symbolic significance. Additionally, Elbe frequently explores unique lighting, as seen in “Poplars Along Hobro Fiord,” where the painting captures the precise moment when the clouds begin to clear, allowing golden rays to illuminate parts of the reflective waters.2

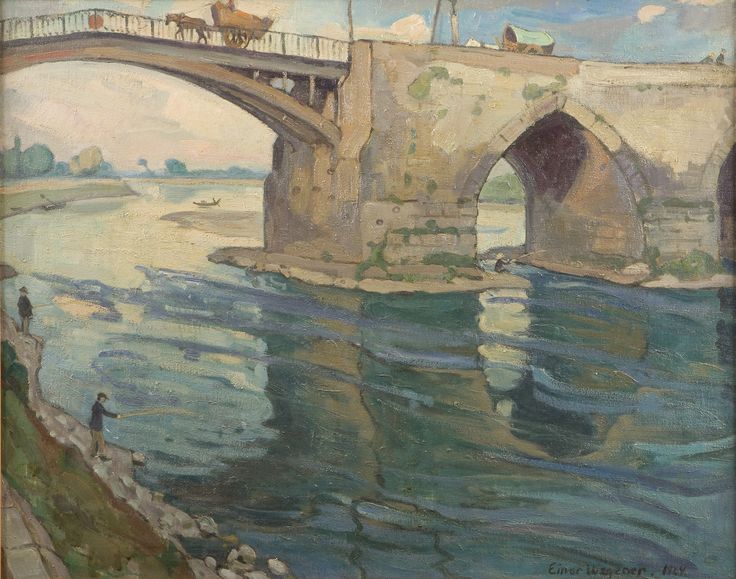

Transition

As mentioned above, many of Lili Elbe’s paintings feature bridges either in the background or the center. Within her autobiography, she specifically describes herself as “a bridge between both man and woman”, as well as between the masculine and the feminine parts of her own personality. Pont sur la Loire is a perfect example of how she used these bridges as a metaphor for her transition. At the center of the painting stands the motionless bridge, stable above and between turbulent waters that transition from dark shades of blue into sunbathing shimmers of pastel turquoise. On the distant brighter blues, the waters appear still and the skies are cloudless, whereas at the darker blues, which are much closer to the observer, the sky is overcast and the waters are fast and unruly. The painting techniques used to convey these different shades and transitions are as complex and layered as its metaphor and show the true artistic skill of Lili Elbe.3

Lili Elbe, Pont sur la Loire, 1924, Trapholt Museum of Modern Art, Craft and Design, Kolding, Denmark.

Female Spaces

After Elbe publicly started her transition, she stopped painting. In her autobiography, she explains that she closely associated her painting with masculinity and, thus, regarded it as increasingly incompatible with her female self. This association was, as mentioned earlier, fundamentally influenced by the artistic conventions of the time which considered Lili Elbe’ works through their category of landscape painting as definitively masculine. Despite ultimately considering her painting incompatible with her transition, Elbe did attempt to create a feminine artistic space within her later works.

This is evident in one of her few portraits, Portrait de Femme (1923), potentially a self-portrait, or in her singular depiction of a woman’s chamber titled An Interior of a Boudoir. Luxuriously adorned in warm hues of deep red and sparkling gold, the Interior of a Boudoir distinctly centers on the female form, absent physically but represented through the discarded women’s clothes strewn across the space. Notably, the miniature paintings on the wall serve as the sole direct representation of the female body within the room, showcasing a harmonious fusion between Lili Elbe’s earlier landscape paintings and the explicit female portraits of her spouse, Gerda Wegener.4

Lili Elbe, An Interior of a Boudoir, 1916, private collection.

Gerda Wegener

Early Works

Gerda Wegener, like her spouse Lili Elbe, showcases an extensive artistic evolution throughout her artworks. In her early works, she was comparatively traditional in her portrait paintings, concentrating primarily on realism. Still, she encountered many restrictions within the, at the time, vastly conservative Danish art community due to her gender and her affinity for new artistic movements.

Her Portrait of Ellen von Kohl was explicitly rejected from several exhibitions due to its subtle influences from Art Nouveau in the patterns of the dress and embellishments, and because it was painted by a female painter. The portrait became part of a wide-ranging debate: it sparked a flurry of responses in the newspaper Politiken, with opinions both in favor and against the spiritualized, refined Symbolism depicted in the image. Those against it were dubbed “the Peasant Painters.” The “Peasant Painter Feud” demanded reformation and gender equality within the Danish art community. Nevertheless, Gerda Wegener had already become disenchanted with the Danish art community and, thus, convinced her spouse to move to Paris in 1912.5

Gerda Wegener, Portrait of Ellen von Kohl, 1906, private collection.

Art Nouveau

In Paris, Gerda Wegener found both freedom and popularity. Painting now in an openly Art Nouveau and later early Art Deco style, she swiftly became a central figure within the Parisian artistic elite. With the liberation of her artistic style, likewise came a diversification of her subject matter. Both before and after she came to Paris, she primarily painted women. However, after arriving in Paris, the figures she depicted and their different expressions of femininity became much more diverse.

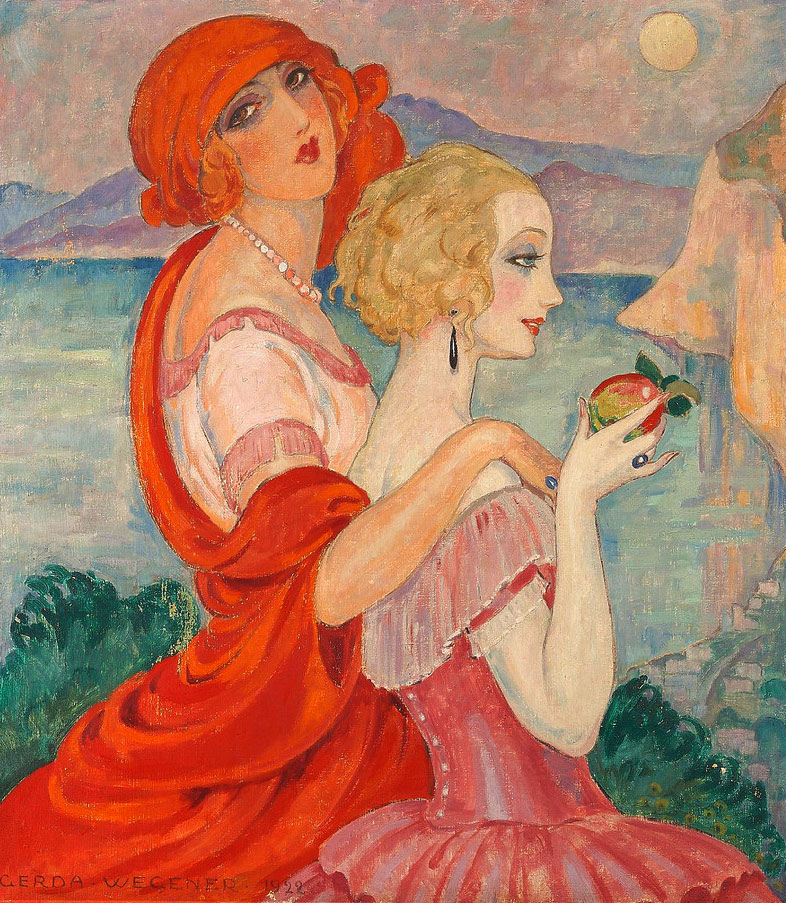

The femininity of the women within her paintings ranged from delicate and traditionally feminine burdened with lace, tiny waists, and wide gowns, to the modern and emerging more androgynous “Garçonne” women with short hair and the more loosely-fitted clothes of contemporary fashion.

Her depictions of women encompassed a range from conventional and neutral individual portraits to placing women within the urban environment and its modernity. She transitioned from subtly suggestive portraits to openly erotic depictions, featuring both individual women and couples engaged in intimate activities. Les Femmes Fatales is an illustration of her more traditional and subtly suggestive portraiture. The painting features three women with androgynous short hair, minimal jewelry except for a simple necklace, and traditional frilly dresses with makeup. Despite these modern touches, their traditional femininity is emphasized through delicate postures, decorative butterflies, and floral motifs.6

Gerda Wegener, Les Femmes Fatales, 1933, private collection. Sotheby’s.

Commercial Art

Due to her extensive popularity during her lifetime, Gerda Wegener was able to financially sustain herself with her art. She, consequently, sold her art in a wide diversity of artistic contexts ranging from prestigious art galleries to postcards and magazines, and even commercial advertisements for beauty and cosmetic products. Woman with Mask, for instance, is one of her many advertisements. It specifically advertises a luxury brand face cream Creme Teindelys in a playful and distinctively Art Nouveau manner.7

Gerda Wegener, Woman with Mask, 1918-1925, private collection.

Lili Elbe and Gerda Wegener

Lili as a Model

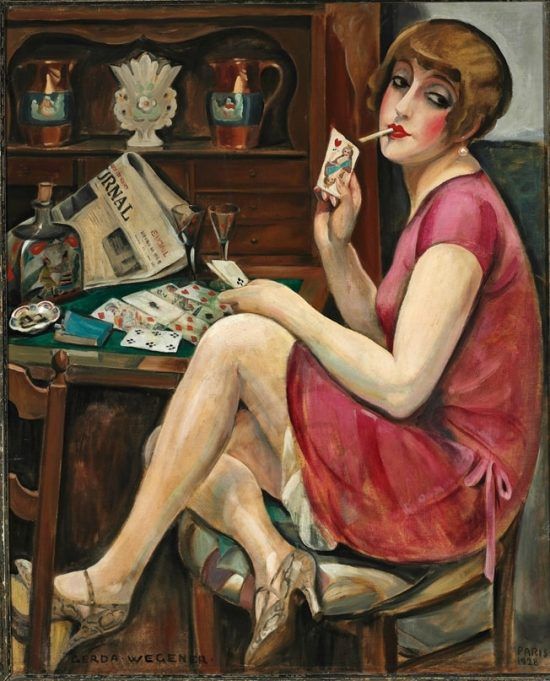

One of Gerda Wegener’s favorite models was Lili Elbe. In her autobiography, Lili Elbe recalls a transformative moment during her transition when actress Anna Larsen couldn’t attend a portrait session with Wegener. Larsen suggested Elbe as a replacement to avoid delays. Both Elbe and Wegener describe Elbe’s liberation through the repeated portrayal as a woman, as depicted in Queen of Hearts (Lili).

Despite written sources portraying Elbe as passively involved, the portraits reveal a confident and active subject. Queen of Hearts (Lili) showcases Elbe as a self-assured model, gazing directly at the observer with ambiguous defiance. The portrait is rich in detail, capturing the graceful posture, Art Deco patterns, and decisive brushstrokes, reflecting Wegener’s deep care for her art and for Lili Elbe.8

Gerda Wegener, Queen of Hearts (Lili), 1928, private collection.

Their Relationship: Legal Issues

The above-outlined differences between what is written within Lili Elbe’s autobiography and her portrayal within her own art and the portraits of Gerda Wegener are particularly important when taking the context into account in which the autobiography was written and published.

As one of the first to undergo gender-affirming surgery, Lili Elbe expressed experiences that had not yet been established within popular or artistic discourses. Furthermore, within the Danish legal context of the time, both the gender-affirming surgery and the change of name would only be legally accepted if the individual could “prove” to the judges to indisputably belong to the according gender. The autobiography should, thus, be regarded as a testament of what, in the popular opinion of the time, was considered womanhood and how Lili Elbe adhered thereto, rather than an accurate and full account of her experiences.

This is especially relevant when considering how the autobiography portrays Lili Elbe as distinctively passive throughout her transition, how it highlights her definitive rejection of her art with its masculine connotations after the public start of the transition, and how it represents her relationship with Gerda Wegener. The autobiography defines the relationship between Lili Elvenes and Gerda Wegener as an exclusively companionable relationship throughout their marriage. However, an open romantic relationship with Gerda Wegener would, at the time, have caused Lili Elbe’ transition to be denied by the Danish legal authorities.

The reason for this was that the Danish legal authorities did not yet consider distinctions between sexual orientation and gender identity, but instead understood transgender identities in an exclusively heteronormative framework. Therefore, if Lili Elbe and Gerda Wegener shared a romantic relationship, it would have most likely been restricted to a most private context to avoid endangering Lili Elbe’ legal status.9

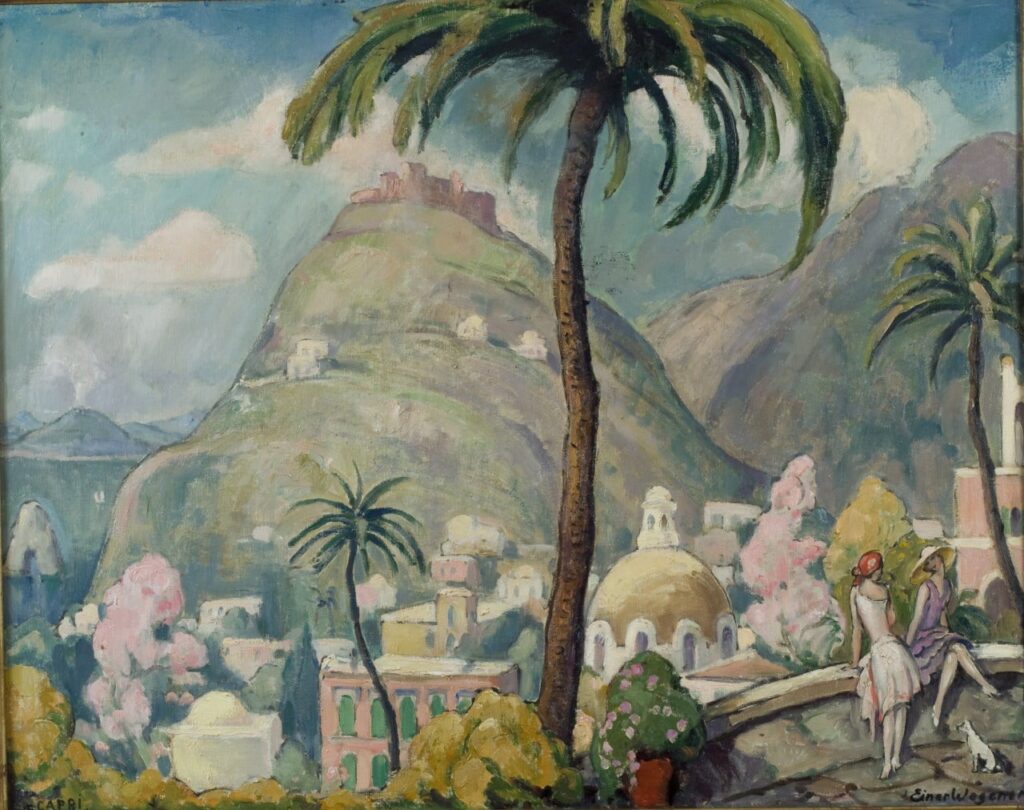

Lili Elbe, Capri, 1922-1923, private collection.

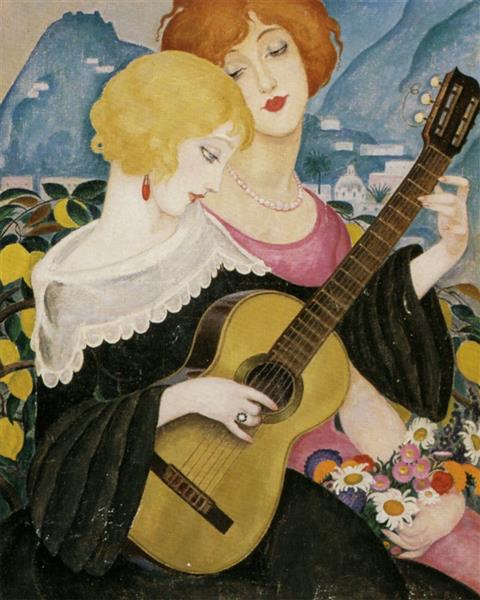

Their Relationship: In Their Art

Examining their art, both generally and the sheer number of portraits of Lili Elbe that Gerda Wegener created, it is apparent that they had a deeply loving relationship. Notably, their shared presence in works like Capri signifies a profound connection. In Capri, Elbe portrays a vibrant landscape with both herself and Wegener gazing into its beauty. Wegener, in turn, captures their closeness in portraits like Sur la route d’ Anacapri and Air de Capri. While these artworks don’t explicitly confirm a romantic relationship, they suggest a caring and complementary bond between Lili Elbe and Gerda Wegener, whether romantic or not.10