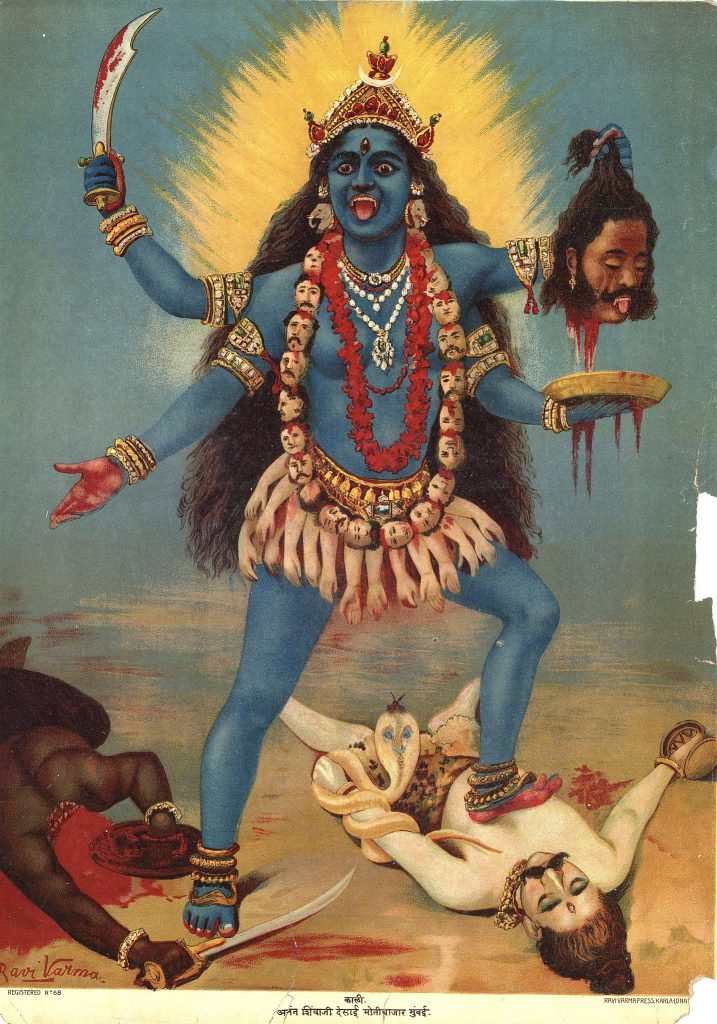

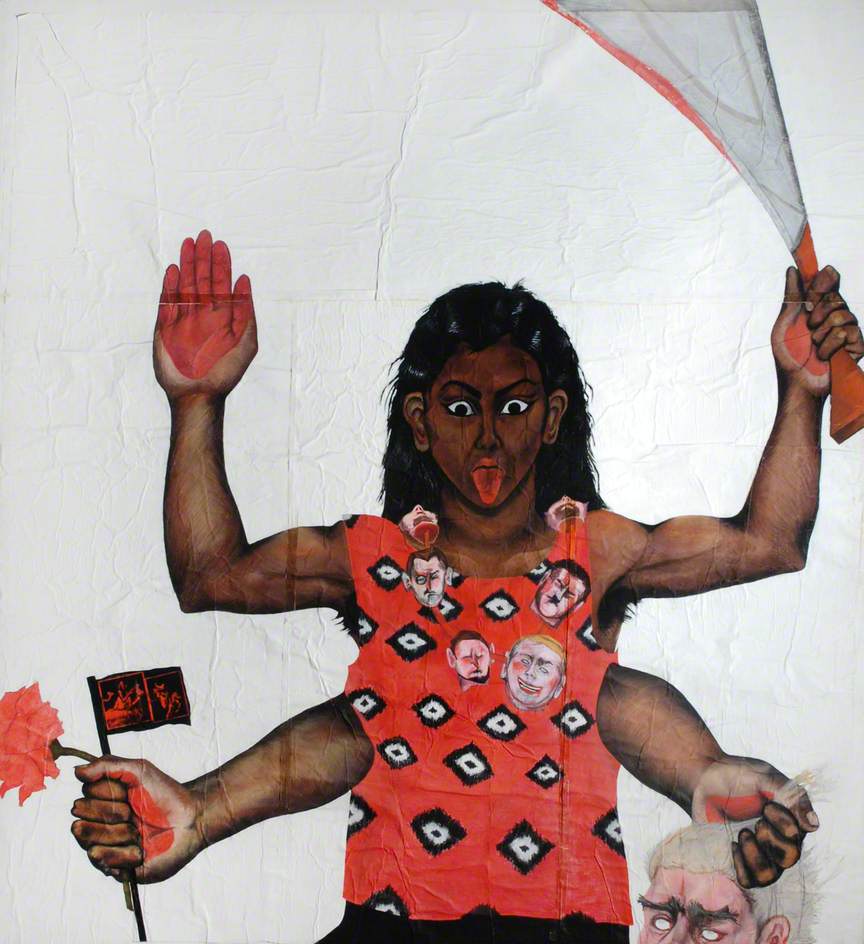

The Tantric goddess Kali represents the warrior woman, the mother, and the revolutionary.

Using a palette of bold colors, Raja Ravi Varma has depicted Kali in her rageful form, incorporating the traditional iconography of the Hindu goddess: she is sticking her tongue out, holding a decapitated head, and wears a string of severed heads around her neck. Wielding a bloody machete, she is mounted on yet another unfortunate, specifically, her husband and the god of destruction, Shiva.

Kali expresses female rage with fearsome confidence and composure. However gory, this manifestation of Kali represents the conquering of evil and the protection of the innocent, with the bloody corpses symbolic of ignorance and infatuation. The painting was produced 30-40 years following the political reclamation of Kali as the protective Mother Goddess.

During the 1870s and 1880s, Bengali people were oppressed by the British Empire and turned to indigenous belief systems to shape their national identity. In protest, followers of Ramakrishna called themselves “the Army of the Mother.” They spread Kali’s fearsome influence across the nation, linking the Indian homeland with the presence of the Mother goddess. Poets, playwrights, and artists infused traditional myths about the Mother with contemporary political interpretations and deeper emotional resonance of the feminine desire to protect her people against subjugation and systemic violence.

Sutapa Biswas depicts a modern interpretation of Kali regarding the treatment of South Asian women by Western society, the political climate of the 1980s, and the oppression of women. Her anger is directed towards white male dictators, who represent the evil in the world that she wishes to protect oppressed people from. In a direct reference to Gentileschi’s depiction of female rage, her painting Judith Beheading Holofernes (c.1620) is printed on the red flag Kali is holding, demonstrating her acknowledgment of the lineage of female artists who have also sought to express rage against their violent subjugation.

Medea by Frederick Sandys (1866-1868)

The tale of Medea from Greek mythology resonates as a narrative of ruthless retribution provoked by betrayal. Medea, born to the King of Aeëtes of Colchis, married Jason, the son of Aeson, after aiding him in his quest for the Golden Fleece. She employed her magical powers to safeguard his life, even killing her brother to lead Jason to success.

A decade and two sons later, Jason’s treachery unfolds as he commits himself to marry Creusa, the daughter of King Creon. He asserts the illegitimacy of his union with Medea due to her foreign origin. Having devoted her all to Jason, Medea is consumed by fury and resolves to reclaim what is rightfully hers. In a devastating act of vengeance, she sacrifices her children, Jason’s betrothed, and King Creon, thus obliterating his lineage and tarnishing his legacy.

Sandys explores the story’s themes of female rage, sorcery, and infanticide by depicting Medea’s evident pain rather than through her typical representation as a femme fatale. Creating the impression that Medea’s sacrificial acts parallel the sacrifices she made for Jason, she crafts the potion used in her murders with a tortured expression.

Further illustrating Medea’s inner conflict, Sandys depicts her tugging at the coral necklace around her neck, a gem typically associated with the protection of children. The two toads in the left corner may symbolize Jason and Creusa’s deceit and the grotesque acts that precipitate Medea’s cruelty.

Dog Woman by Paula Rego (1994)

Paula Rego’s artworks encompass themes relating to childhood, sex, fairytale, and trauma. By rejecting the depiction of women according to conventional beauty standards, Rego forms a particularly distinctive style that is often surreal, disturbing, and emotionally bold.

Unapologetic women are central to Rego’s oeuvre, a motif encapsulated by her oil pastel drawing, Dog Woman (1994). It overtly challenges the societal expectation placed on women to exhibit ladylike and docile behavior. However, the woman as a dog also refers to the socially and politically oppressive environment in which Rego grew up and subsequently learned obedience and subservience. This “dog woman” rejects such treatment. She is aggressive, snarling, feral, and tormented, yet nonetheless unashamed in her refusal to comply with the social standards that oppress her.

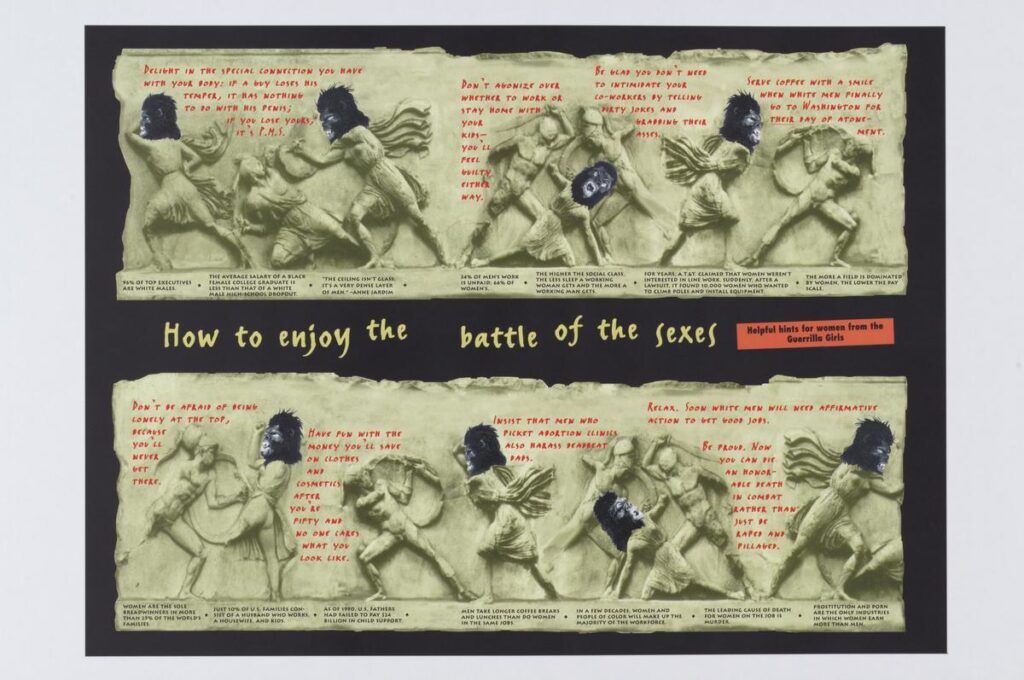

Battle of the Sexes by Guerrilla Girls (1996)

The Guerrilla Girls are famous for disrupting the patriarchal structures of the art world and society at large. In undiluted rage, they eloquently highlight systems of injustice through their art, protests, and rallying posters. They challenge the notion of individualism and ownership by concealing their identities with gorilla masks, as illustrated in this print, The Battle of the Sexes (1996).

Using the imagery of an Ancient Greek frieze, a civilization recognized in the art world as superior, the Guerrilla Girls adorned the classical figures (in the throws of a battle) with their iconic mask. Surrounding them are inscriptions listing the injustices and challenges that women, people of color, and working-class people face in the context of white, elitist, and patriarchal dominance. Witty comments addressing themes of unequal parenting, an unbalanced job market, and male violence are backed up by supporting evidence along the bottom.

Their statements include “Don’t agonize over whether to work or stay home with your kids – you’ll feel guilty either way,” “insist that men who picket abortion clinics also harass deadbeat dads,” “the average salary of a black female college graduate is less than that of a white male high-school dropout,” “the more a field is dominated by women, the lower the pay scale,” and “prostitution and porn are the only industries in which women earn more than men.”

The Guerrilla Girls not only express defiance towards such systems but masterfully stir feelings of female rage within the viewer, as evidently, there is a lot to be very angry about.