Between Word and Image: The Creative Mind of David Jones

David Jones (1895–1974) was an artist, poet, writer and craftsman; a name synonymous with the Modernist era but one that still remains lesser known...

Guest Profile 21 October 2024

Kay Nielsen is one of the most illustrious names associated with the Golden Age of Illustration in the latter half of the 19th century. With a boom in printing and book publishing, especially in luxurious fine art books, many artists had a new outlet for their artwork: children’s illustration. However, among his contemporaries there were few that managed to capture the imagination of both adults and children in the same manner as Kay Nielsen.

Often, illustration remains in the wings of art history discourse. This could be partially explained by its dependence on text, as well as its relationship with applied arts. It is closely associated with women’s labor, decoration, and cozy, domestic hobby work of creating ornamental frivolous goods. However, there are a myriad of artists that contributed to and even influenced major art movements, such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco through their work. They also successfully blended textile and stage design, together with symbolism prevalent in art. One such example that stands in mind is Kay Nielsen.

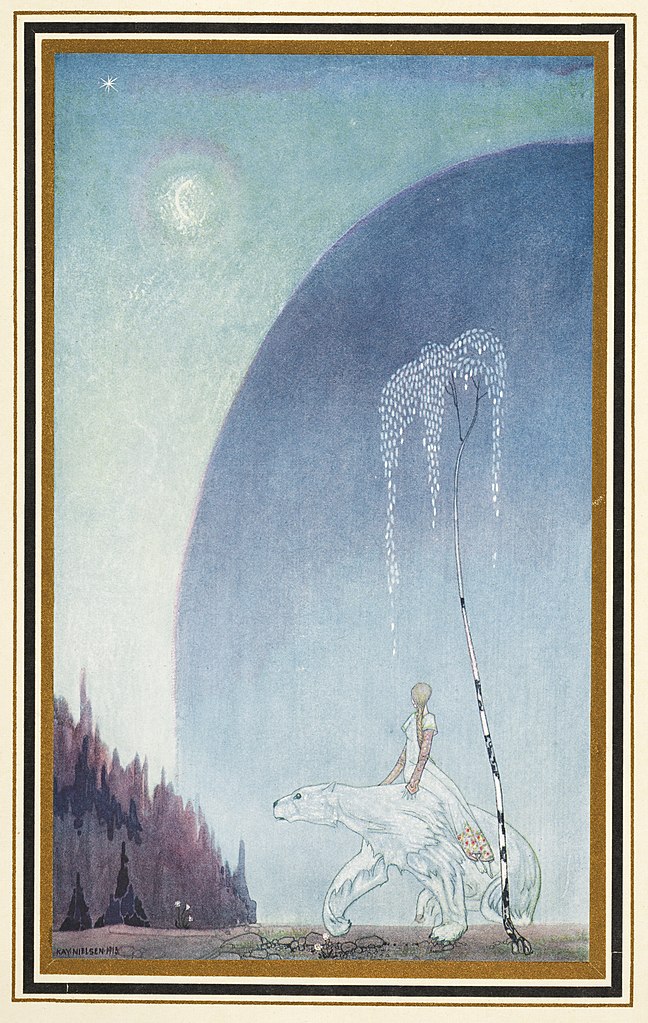

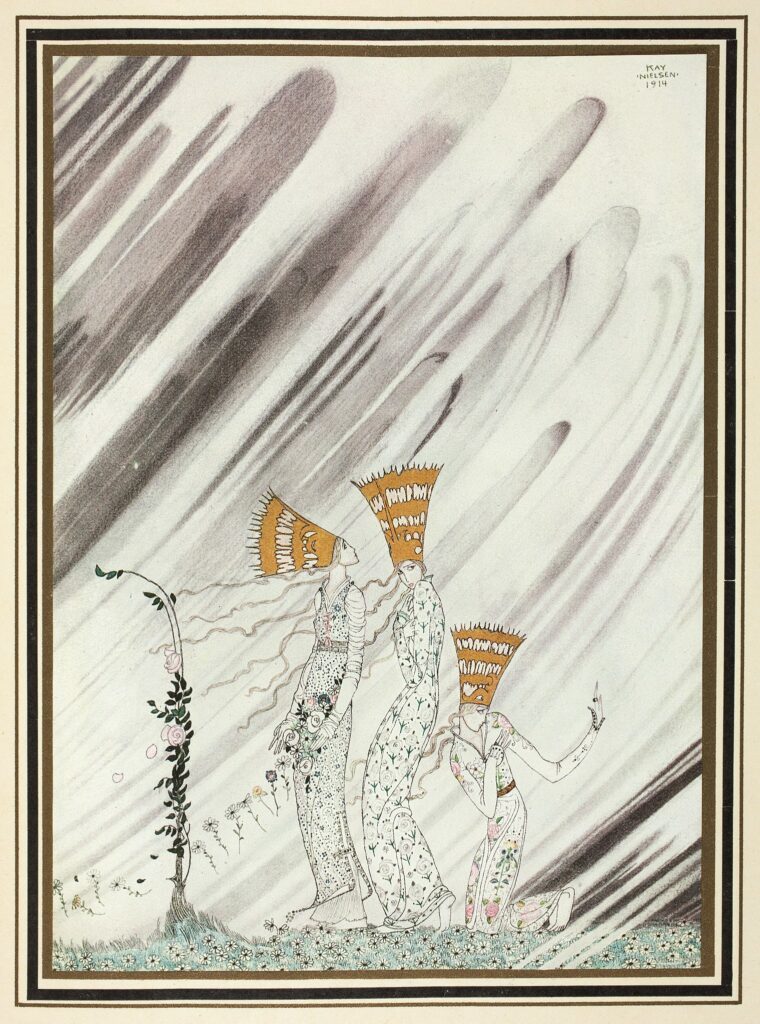

Kay Nielsen, Hold Tight to My Shaggy Coat from East of the Sun, West of the Moon, 1914, The National Library of New Zealand, Wellington, New Zealand.

Kay Nielsen (1886-1957) was a Danish illustrator who worked in the first half of the 20th century. He was born in Copenhagen, and studied art in Paris. He subsequently moved to London to pursue his career in 1911. His first breakthrough was a commission of the French series of fairy tales, In Powder and Crinoline, published in 1913.

Nielsen is renowned for his enchanting worlds. His illustrations cast a wide net of geographical and cultural settings – from Norse mythology and Germanic fairy tales to Persian tales of kings. He illustrated many familiar European favorites, such as Hans Christian Andersen’s (1924) and Brothers Grimm’s Fairy Tales (1925), as well as Nordic folk tales East of the Sun, West of the Moon (1914) and Arabian Nights (1976).

Kay Nielsen, Rosebud from Hansel and Gretel, and Other Stories by the Brothers Grimm, 1925. WikiArt.

Furthermore, he contributed to the early work of Walt Disney’s studio, notably Fantasia (1940). He was one of the European illustrators selected to help recreate the atmosphere of European villages for the settings of the first animated feature films, notably Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937) and Pinocchio (1940). Nielsen also contributed conceptual artwork for the The Little Mermaid, although developed posthumously, only in 1989.

However, his style and penchant for the dark and visually ominous, quickly fell out of favor at the Disney studio, as his works were considered too strange and would instill fear in children. Nielsen did not agree with this opinion and did not share the cookie-cutter approach to animation. This artistic shift in Walt Disney’s studio could also be partially explained by the impact of the Second World War, as a move away from ‘moral ambiguity’ and towards more puritanical values.

One of the hallmarks of Nielsen’s style is the emphasis on the setting over the characters, creating a truly immersive experience for the viewer. What sets him apart from his contemporaries, such as Arthur Rackham and the Robinson brothers, is the diversity of the cultural influences he draws upon in his works. These include Celtic mythology, Persian miniature painting, Japanese ukiyo-e prints, and Western European illustration.

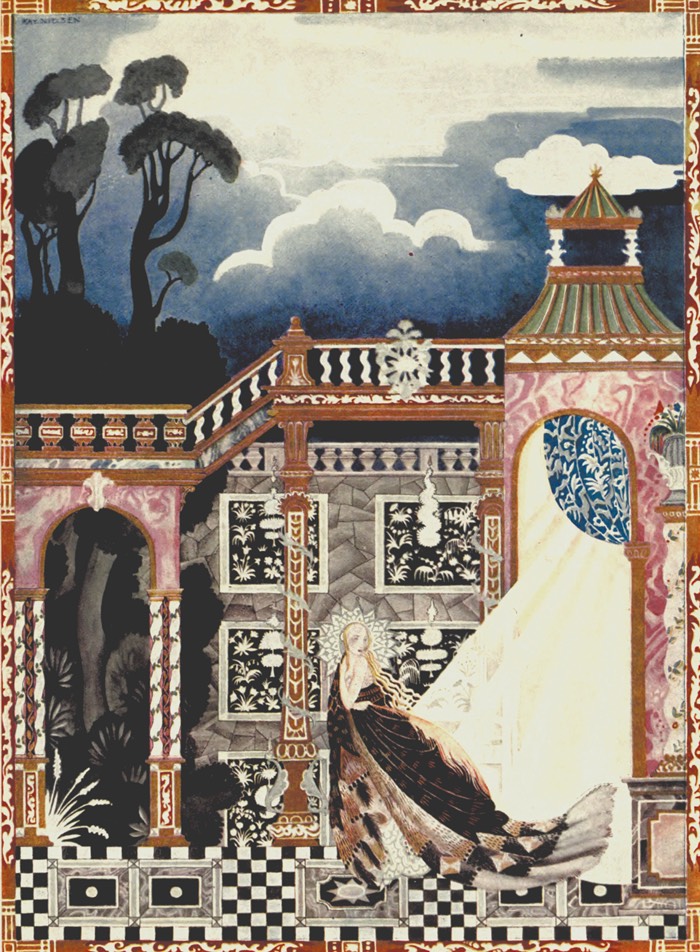

Kay Nielsen, Catskin from Hansel and Gretel, and Other Stories by the Brothers Grimm, 1925. WikiArt.

For instance, the ample decoration in attire and elongated figures can be attributed to Celtic inspiration. However, the flat, house-of-cards style architecture, often in a two-dimensional projection shows close links to the Persianate way of representation. Nonetheless, the overarching theme that could encompass the majority of Nielsen’s work is the emphasis on decoration and set design evinced in his rich ornate settings and protagonists’ lush garments.

This influence stems from theatrical circles that the artist was immersed in due to his parents’ occupations – his mother was Oda Nielsen, a renowned Danish actress, while his father, Martinus Nielsen, was also an actor and a director. While on his sojourn to Paris, he took note of the Ballet Russes from which he drew inspiration evident in his costume design especially well.

Kay Nielsen’s strong emphasis on the setting is a strong link to his theatrical background. Nielsen focuses on the surroundings and embellishes them in a myriad of ways, whether it’s a meadow or a palace. Thus, the characters often appear to blend in with their environs. Moreover, in his works, the setting often takes center stage itself. It sets the stage for Nielsen’s characters, whereby the drama occurs.

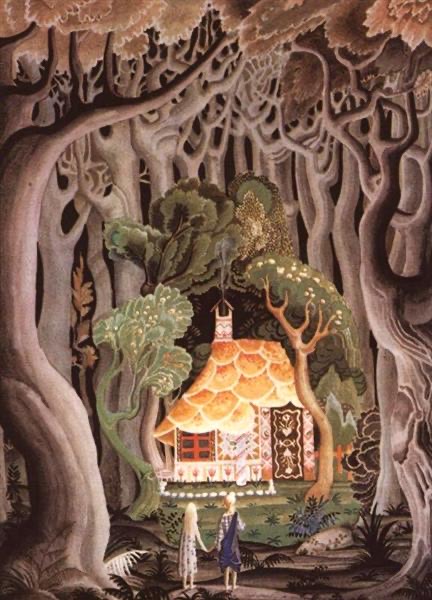

Kay Nielsen, Hansel and Gretel from Hansel and Gretel, and Other Stories by the Brothers Grimm, 1925. The Pook Press.

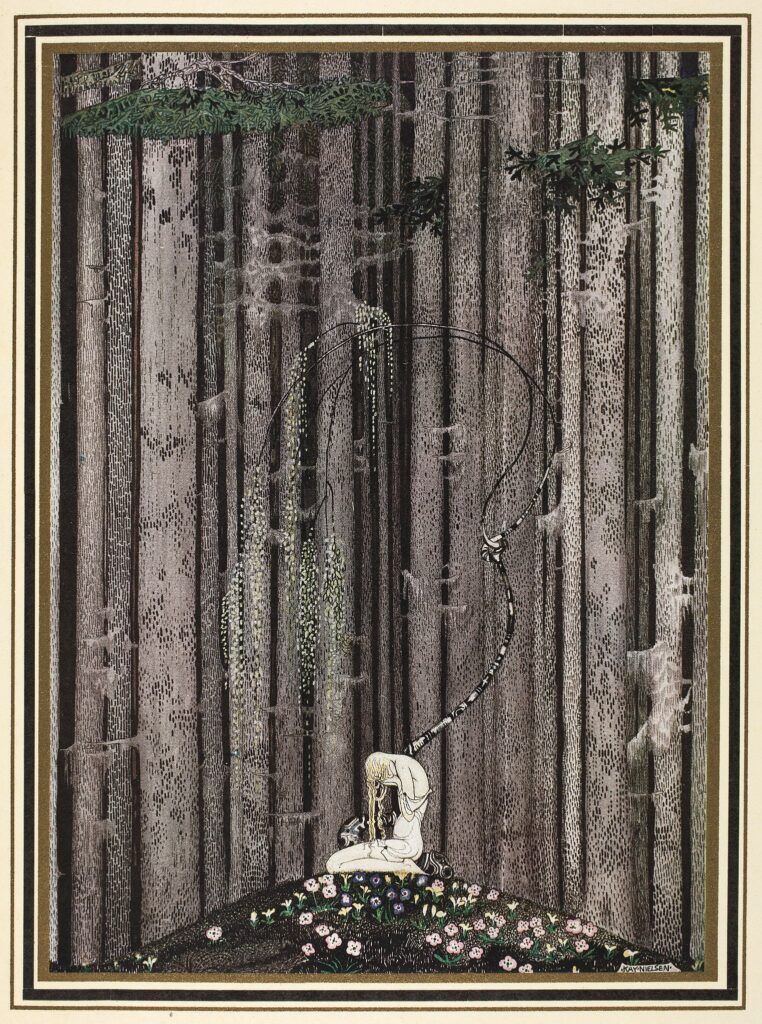

However, the sheer amount of detail that is poured into every composition is astounding. Each element in nature, under Nielsen’s apt wielding of the brush, becomes stage decoration. For instance, he often uses trees and their trunks to create the effect of a dense thicket, especially evident in Hansel and Gretel, Rosebud, and the East of the Sun, West of the Moon volume, which is a pertinent setting for the Norwegian tales.

This influence can be further found in the forest scene in Disney’s animation of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937). His stylistic choices of darker color tones and shrouded backgrounds, especially in the natural setting, influenced Walt Disney’s early animated films’ Gothic and noir appearance.

Movie still from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, directed by David Hand, 1937, Walt Disney Studio. AnimationScreencaps.

Even though it can be considered a stylization, Nielsen emphasizes the organic quality of nature through exaggerated fluid forms of trees, plants, and clouds, among other formations – especially evident in Juniper Tree. The elongated and viscous forms of plants and shrubbery that softly sway in the wind remind of an underwater world that is prone to change and metamorphosis – an apt choice when illustrating tales that entail many transformations. These qualities are also reminiscent of Surrealist art. Another link that unites him with the movement is the blurring of the boundaries between myth and reality.

Kay Nielsen, Juniper Tree, from Hansel and Gretel, and Other Stories by the Brothers Grimm, 1925. WikiArt.

Nielsen’s use of dramatic lighting is also part and parcel of his theatrical background, evident in the stark contrasts of his nocturnal scenes, such as in Catskin and Juniper Tree. At the same time, his preference for night scenes or dusk as a background setting could point to his Danish roots and the gentler lighting effects that are prevalent in Scandinavian countries.

Despite being a dominant feature, his architecture often appears fragile, akin to a house of cards or stage props. This reinforces theatre as one of his main sources of inspiration. Simultaneously, it is worth mentioning that the style of ‘house-of-cards’ architecture is a hallmark of Persianate painting. This trope is especially evident in the Catskin illustration, thus suggesting that there could be several influences on his style.

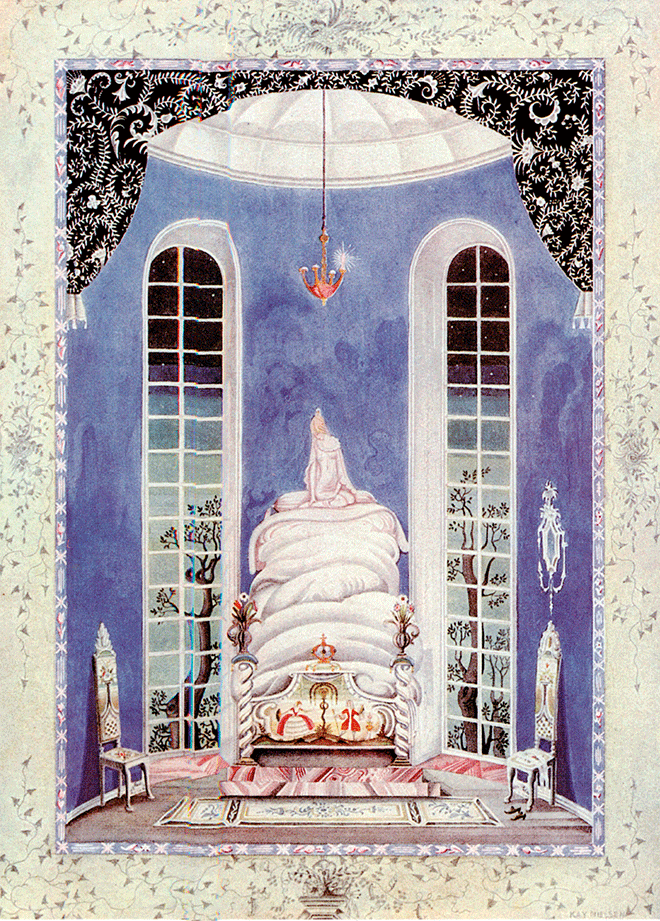

Kay Nielsen’s works are also tightly interwoven with Romanticism – an art movement that strongly associated itself with the celebration of Northern identity and separation from the classical art canon. In the spirit of Romanticism and the historic revivalist movement especially felt in Great Britain, Gothic architectural elements, such as tall windows, are featured in Nielsen’s works as well, notably in The Princess and the Pea.

Kay Nielsen, The Princess and the Pea from Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen, 1924. The Pook Press.

The architecture and surroundings often frame the characters in such a way that they demonstrate how the environment, predominantly nature, is larger than them. This theme was very popular in Romantic art, evident in works by 19th-century German landscape artist, Caspar David Friedrich. Nielsen’s environs mostly tend to overwhelm his protagonists, as seen in The Princess and the Pea and Rosebud.

His works are also filled with the Romantic notion of the sublime – the overwhelming and awe-inspiring emotion a person experiences when exposed to nature, especially to its elements and forces, such as majestic views atop a mountain, clouds gathering in anticipation of a storm, among others. Nielsen aptly demonstrates this, as his characters never exist in a void. They are always surrounded by forces of nature or complex interiors that surmount them.

Kay Nielsen, A Snow Drift Carried Them Away, from East of the Sun, West of the Moon, 1914.

Even when the protagonists are depicted against the sky, the air has a quality of vitality – it is constantly in motion. For example, in Snow Drift Carried Them Away, the three figures stand against a dramatic backdrop of powerful gusts of wind that surround them. Nielsen’s significantly low placement of the horizon line intensifies the drama, thus enhancing the atmospheric effects. The slender figures appear even more fragile in this context.

By emphasizing the detail in fabrics and various architectural elements, Nielsen celebrated the decorative arts quintessential to the revival of medieval art (that Romantic art is often associated with). As a result, his visual narrative is just as rich and multifaceted as the stories he illustrated.

His protagonists are illuminated and often dressed in white, setting them apart from the background. At the same time, the intricately decorated setting highlights their ethereal quality. However, Nielsen aptly combines the tightly knit tapestries of details with airy spaces, creating a balanced composition.

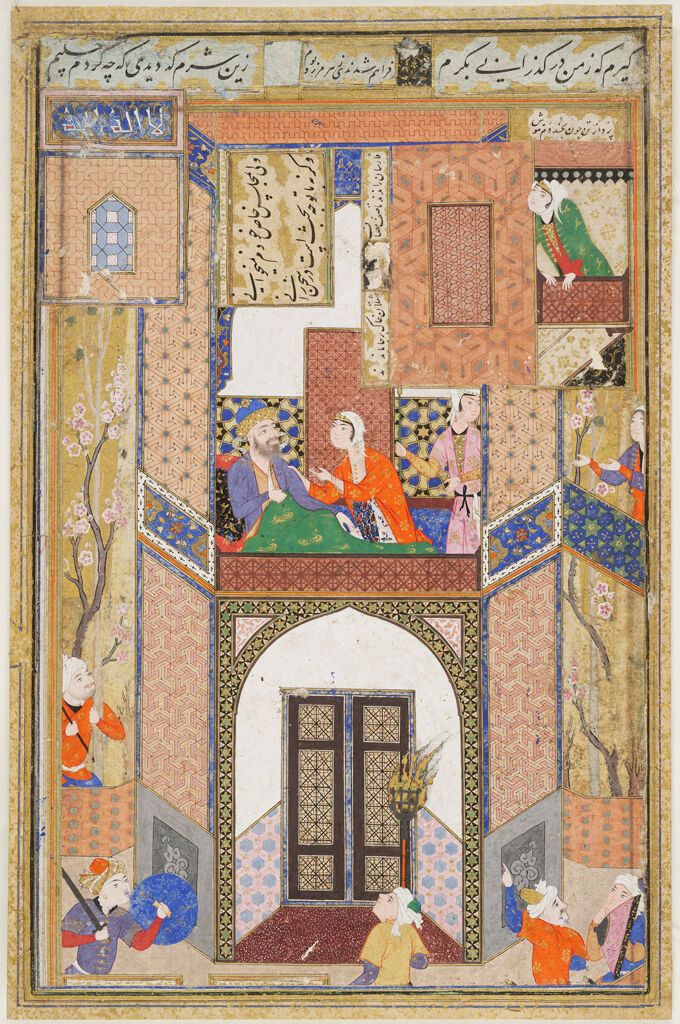

Nightmare of Zahhak from a manuscript of Ferdowsi, Shahnama (Book of Kings), 16th century, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Simultaneously, such ‘compactness’ of a single composition can point towards the influence of Persianate miniature painting. As shown in the illustration of Nightmare of Zahhak, Persian artists aimed to include as much information as possible within one image. Examples of this include two narratives, background scenery (notably a tree in bloom), text, and a frame that surrounds the image.

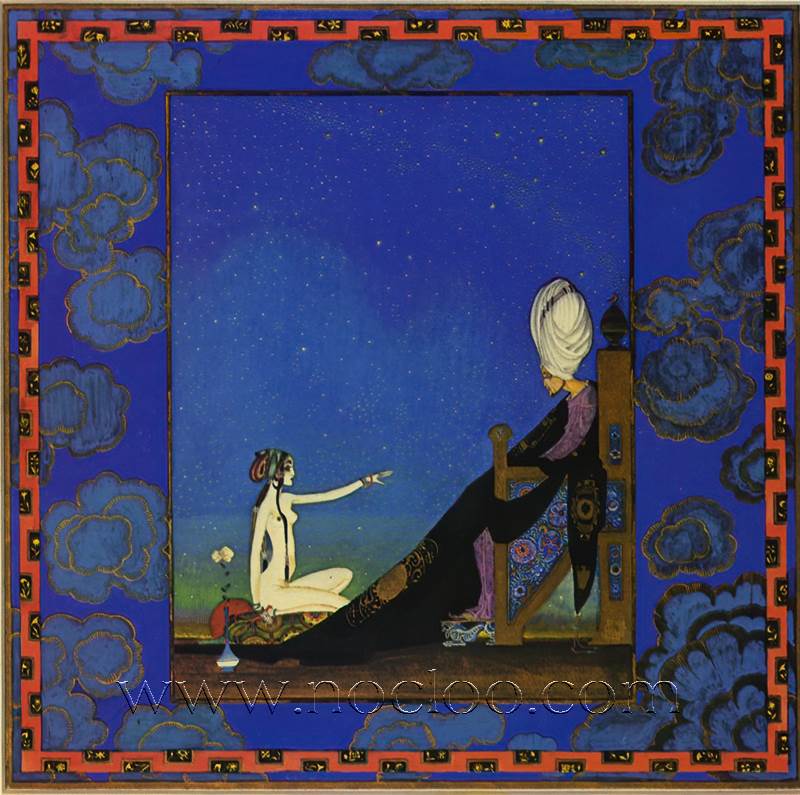

The emphasis on ornament and dispensing with perspective are also tropes found in both Persian and Mughal painting that are again seen in Nielsen’s Catskin illustration, further suggesting how broad his scope of influences was. He even illustrated a book on Arabic tales, Red Magic (1930), as well as Arabian Nights (1976).

Kay Nielsen, Illustration for the Arabian Nights, 1976.

Elsewhere, Nielsen imitates the perforated technique to depict plants. He uses black and white stencils for occasional shrubbery and set decoration (plant life in Juniper Tree and wall hangings in Catskin) that enhance the two-dimensionality of the composition. Moreover, this flat, representational style in illustration and graphic design would become very popular during the Art Deco period in the 1920s. The allusion to such techniques emphasizes Nielsen’s link to craft – stage and textile design and other craft techniques. These bode well with and complement illustration of traditional and folk tales from the North, as they are entrenched in local history and lore.

Kay Nielsen was a fantasy visionary who contributed to and helped to shape the Golden Age of illustration, as well as the early visual language of the Western animation. His works echo today in both Japanese manga books and classic Disney animated movies. The variety of influences make him one of the most versatile and unique artists who illustrated fairy- and folktales. At the same time, he successfully positioned his oeuvre within the canon of Romantic art by placing nature at the center of his compositions, while paying homage to another strand of Romanticism – craft and applied arts.

Kay Nielsen, In the Midst of the Gloomy Thick Wood from East of the Sun, West of the Moon, 1914, The National Library of New Zealand, Wellington, New Zealand.

Author’s bio:

Anna Shevetovska is an arts writer based in Scotland. She received a master’s degree in art history from University of St Andrews and majored in product design in her undergraduate degree. Shevetovska is also an avid practitioner of art and frequently sketches or creates watercolors at home or outside. She enjoys walks in nature and exploring museums.

Kay Nielsen Biography, The Pook Press. Accessed on 7 Feb. 2024.

Pete Beard: Unsung Heroes of Illustration 4, YouTube. Accessed on 7 Feb. 2024.

Greg Cook: Illustrator and Disney Artist Kay Nielsen’s Glittering Fantasies, August 14th, 2019, Wonderland. Accessed on 7 Feb. 2024.

Carey Dunne: The Dark, Enchanted Worlds of Illustrator Kay Nielsen, February 22, 2016, Hyperallergic. Accessed on 7 Feb. 2024.

Meghan Melvin: Kay Nielsen, Society of Illustrators: The Museum of Illustration. Accessed on 7 Feb. 2024.

Amber Sparks: “The Original Little Mermaid”, The Paris Review, March 16th, 2018. Accessed on 7 Feb. 2024.

Ruijingya Tang: “Enchanted: The elegant otherworlds of Kay Nielsen born from masters of the past”, The Tufts Daily, October 8 2019. Accessed on 7 Feb. 2024.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!