Hanuman: The Revered Monkey God in Hindu Mythology

The revered monkey god Hanuman is one of the most iconic in Hindu mythology. He embodies unparalleled strength, unwavering devotion, and boundless...

Maya M. Tola 19 September 2024

The history of modern Korean art is closely linked to the historical events unfolding in the country at the time. The 20th century was a very eventful time which saw Korea’s fall under Japanese occupation (1905–1945), the outbreak of the Korean War (1950–1953), the struggle for technological modernization and economic survival (1953–1979), and eventually, the country’s rise to being one of the most developed nations in the world. This process was captured by the local artistic community and reflected in the 10 artworks below.

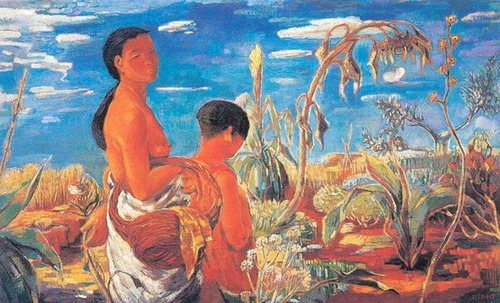

20th-Century Korean Art: Lee In-Seong, One Autumn Day, 1934, Hyundai Gallery, Seoul, South Korea.

The period of the occupation was one of poverty and repression for the ordinary citizens and for the most part, it was hard to buy (and, at times, even find) painting materials. Yet, painters did exist and, in fact, a large-scale Joseon Art Exhibition was hosted almost every year between 1922 and 1944. However, the show was organized by the colonial authorities and consisted mostly of propaganda paintings which often depicted small, rural areas to imply the backwardness and underdevelopment of the Korean people.

Lee In-Seong’s One Autumn Day is one of the most infamous paintings of the period which is still considered controversial for borrowing heavily from Paul Gauguin and for its voyeuristic representation of Korean people.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the liberation movement began to pick up pace with much of Korean society focused on opposing the foreign presence. This left a mark on the art of the times—many painters emphasized the longing for a new era, the foretaste of a possible different fate, and the desire for a dreamy elsewhere. Most of the works from this period were lost during the Korean War (1950–1953), but those that remain are considered part of the canon of Korean art heritage for their meaning and rarity.

Kim Eun-Ho, Buddhist Dance. MutualArt.

After the war, the key question with which the Korean art society was struggling was how to cleanse itself from the Japanese influence. Over the years of the colonial period, much of the country had been modernized but this was a modernization with a Japanese tint. The cultural practitioners of the time saw it as their mission to discover Korea’s uniqueness, something truly theirs that was to form the core of the further development of arts and culture. This resulted in a heightened sensitivity to everything non-Korean and foreign and a very clear distinction between what themes and techniques are imported from the West and Japan and what is strictly part of the pre-occupation Korean tradition. This sensitivity exists today and it is considered the mark of a true Korean artist to find a way to develop something truly Korean in an authentically Korean way.

Notable artists of the period include Lee Quede, Lee Jung-seop, and Lee Ungno.

20th-Century Korean Art: Lee Quede, Self-portrait in Traditional Coat, 1940s. Korea.net.

Lee Kweedae is often referred to as “the Korean Michelangelo.” His Self-portrait in Traditional Coat depicts the artist as a man on duty who has to help lead society into the new era, who has to help a generation make sense of its collective fate. There is an unmistakable flare of dignity in his eyes and a posture that reflects the newfound sense of optimism and confidence.

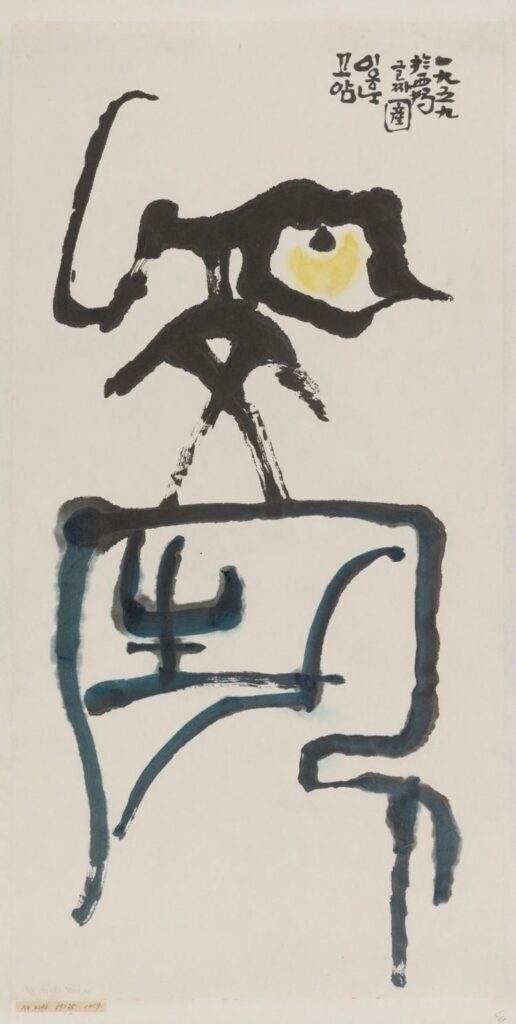

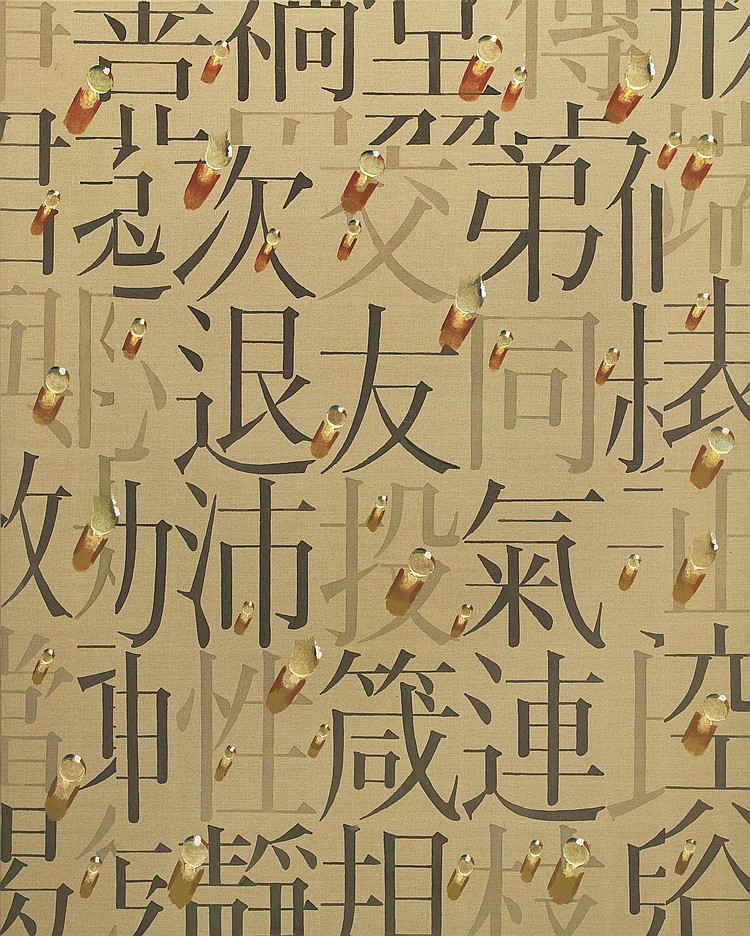

20th-Century Korean Art: Lee Ungno, Calligraphy, 1959. Amis Musee Chernuschi.

Lee Ungno’s Calligraphy from 1959 is another signature piece from the period. The artist depicts the Chinese character for the verb “produce” and styles it to resemble a person on a cliff.

Following the end of the war in 1953, most of South Korea was destroyed. The country needed assistance from the USA to build an export-oriented economy, if it was to survive the ravages of the military conflict. This led to the political establishment actively pursuing a policy of modernization and “catching-up” with the rest of the world in all areas of arts and sciences. The sudden influx of European painting styles led to many artists going down the road of copying before shifting gears and starting to look for ways to mix and match Western and Eastern approaches to express something contemporary Korean.

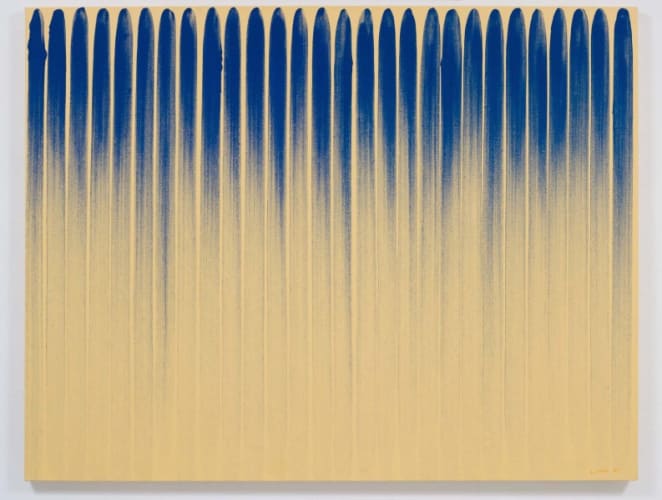

20th-Century Korean Art: Lee Ufan, From Line N8, 1980. ArtBasel.

This is how the Informel movement emerged. It was a mixture of American Abstract Expressionism (which emphasizes the action involved in painting the canvas) and French Informel (which emphasizes both the action and the texture of the canvas), both of which were distilled to leave only those elements deemed fitting for the Korean mentality and sensitivity.

The works of the period aimed to capture subjective feelings in irregular outlines—it was this ambiguousness and the uncertainty of the message that perfectly captured the formative processes of the emerging post-war modern Korean identity.

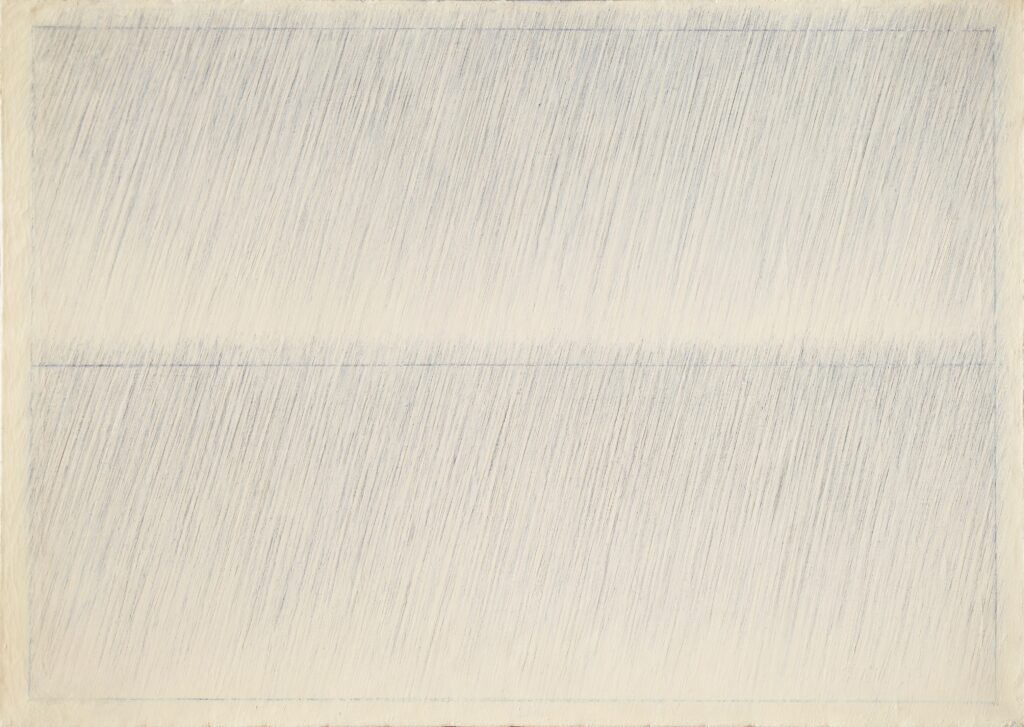

20th-Century Korean Art: Park Seo-Bo, Ecriture N1, 1967. ArtBasel.

Later on, Informel developed into Dansekhwa, the most famous and best-selling modern Korean art movement. Dansekhwa combines Korean simplicity and Buddhist meditation in off-white artworks. Throughout Korean history, off-white colors have played a significant defining role—historically, Koreans were often referred to as “the people dressed in gray” and they consider the famous moon jars (usually white) to be a representative of Korean craft.

Many artworks feature the traditional Korean hanji paper (thick and crude paper made of mulberry tree pulp) which is

also creamy in color. The artists created the artworks in a state of semi-meditation which called back to the country’s Buddhist roots.

Leading artists of this period include Park Seo-bo, Lee Ufan, and Kim Tschang-yeol.

20th-Century Korean Art: Kim Tschang-Yeol, PA93020, 1993. WikiArt.

The introduction of Western ideas and artistic practices led to a period of hodgepodge art experiments commonly referred to with the umbrella term avant-garde which included everything and anything—any sort of experimentation with styles, themes, mediums, performance art, etc.

The Minjung Movement (1970–80s) was a reaction and a counterweight to this and aimed to bring back the Koreanness in Korean art. Even Dansekhwa was criticized as part of the general critique of Abstraction. The Minjung movement saw Abstract Expressionism as a form of turning inward and pursuing only formative beauty as a result of capitalism-induced loss of identity and loss of connection to roots and community. For the Minjung artists, art had to have a live connection with the society it had originated in and it had to reflect ongoing and relevant issues. Within this definition of the role of art in society, Western Abstraction seemed lacking because it reduced art to a formalistic decoration.

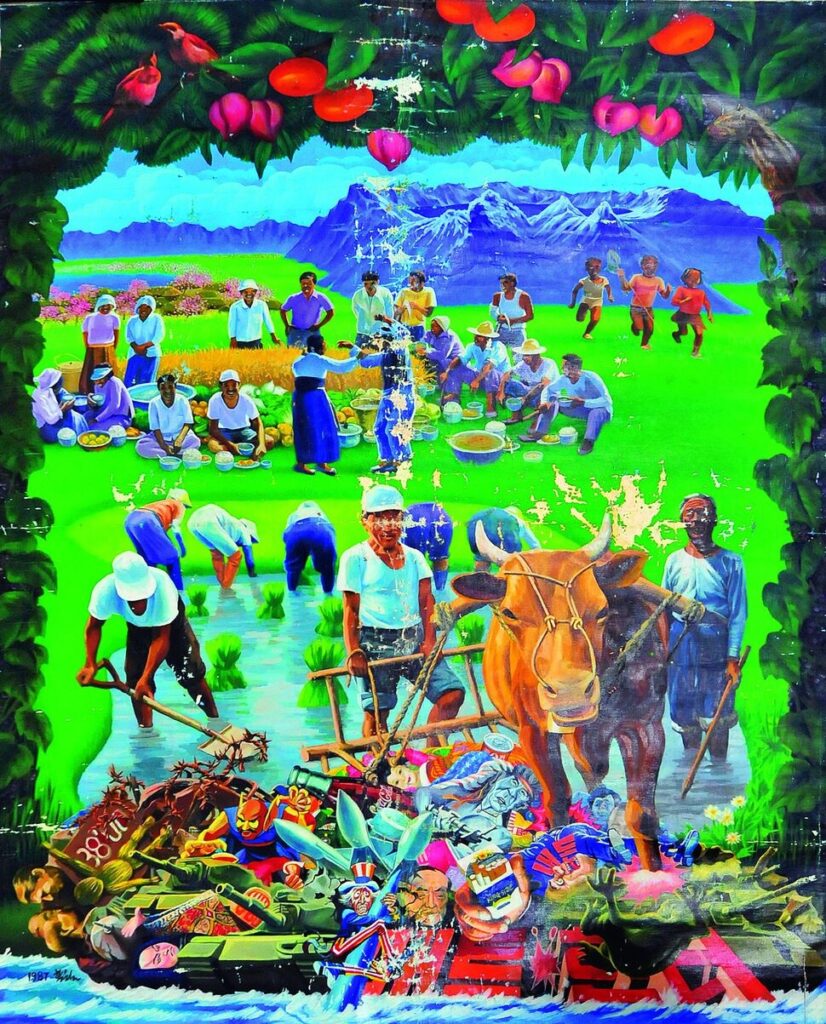

20th-Century Korean Art: Shin Hak-Cheol, Planting Rice, 1987. Hankyoreh.

The leading painters of the period, such as Shin Hak-Cheol, Hong Seong-Dam, and Kang Yo-Bae, had a notably patriotic and folkish style that aimed to rediscover and re-highlight Korean history, nature, daily life, and traditions.

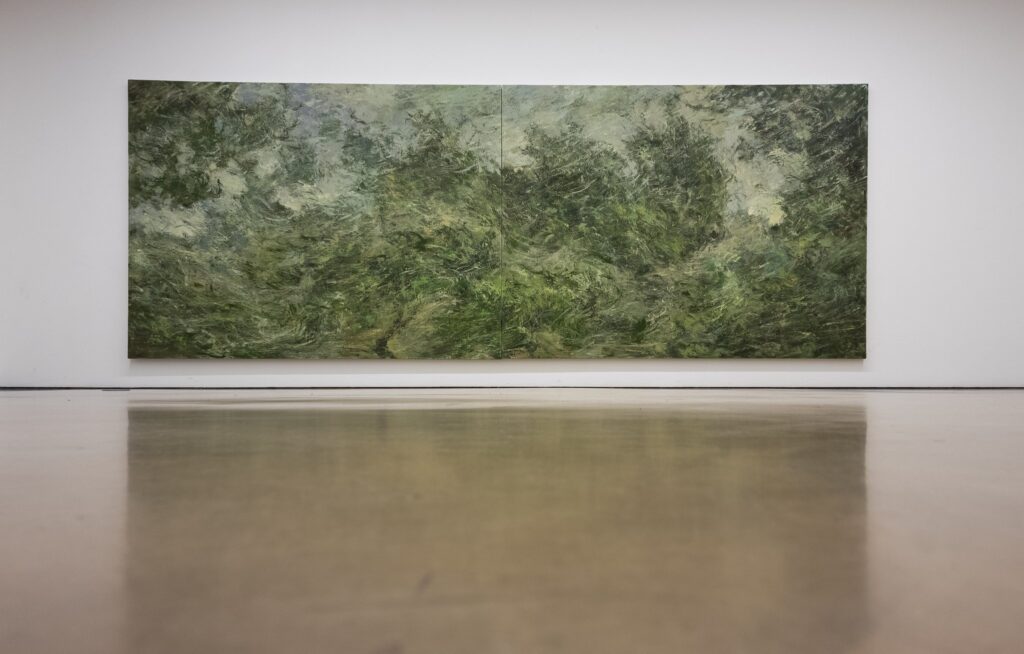

20th-Century Korean Art: Kang Yobae, The Garden, 1980s. Courtesy of the author.

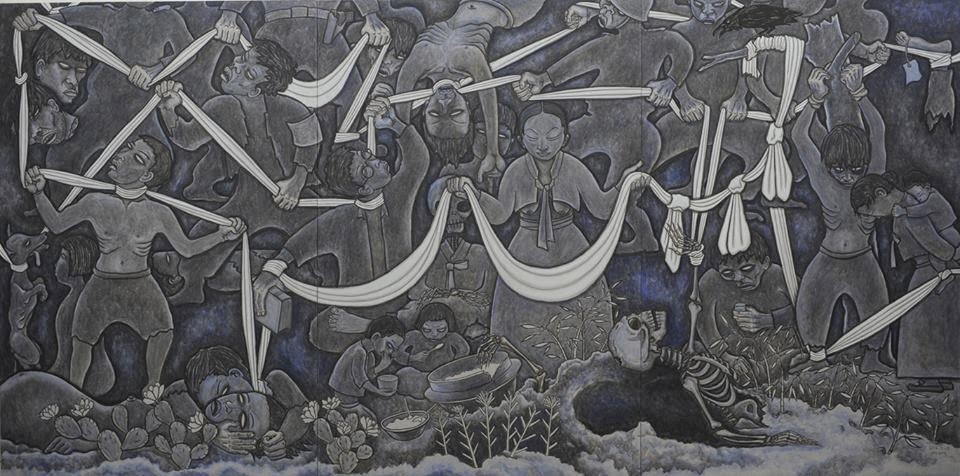

20th-Century Korean Art: Hong Seong-Dam, Jeju 4.3, 2014. Tumblr.

The last decade of the 20th century, and in particular the end of the Cold War and the 1988 Seoul Olympics, concluded the process that had started at the onset of the century—Korea was now open to the rest of the world, integrated into the global trade system and economically developed. These achievements led to a rapid globalization craze and liberalization of overseas travel (prior to 1988, Koreans willing to travel abroad needed to obtain permission from the government), which further intensified the exchange of cultural and artistic influences.

As a result, the Korean art scene became a melting pot for diverse tastes and techniques with artists creating in virtually every genre and subject matter.

Learn more about what is going on in the contemporary Korean art scene today on OnKoreanArt.com.

Author’s bio:

Yana Stancheva is an art writer and cultural entrepreneur. She has been published in several art and culture magazines across the world, always exploring art from East and South-East Asia. Founder of OnKoreanArt.com.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!