Masterpiece Story: Wheatfield with Cypresses by Vincent van Gogh

Wheatfield with Cypresses expresses the emotional intensity that has become the trademark of Vincent van Gogh’s signature style. Let’s delve...

James W Singer 17 November 2024

25 March 2024 min Read

Diana and Actaeon by Jean-François de Troy is a French masterpiece blending the exuberance of Rococo sensuality with the intellectualism of classical mythology.

Jean-François de Troy (1679-1752) was one of the leading Rococo painters of 18th-century France. He specialized in genre scenes of upper-class Parisian life, but his expertise also extended to religious and mythological scenes. Troy enjoyed fame equal to Antoine Watteau and François Boucher, however, his fame was not to last beyond the end of the Ancien Régime when he faded into 19th-century obscurity. Thankfully, in the last 30 years, his reputation has been revised and reevaluated. For example, Diana and Actaeon is a masterpiece of Troy’s career. It blends the exuberance of Rococo sensuality with the intellectualism of classical mythology. It stands as a testament to Troy’s forgotten artistic brilliance.

Jean-François de Troy, Self-Portrait, 1741, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France.

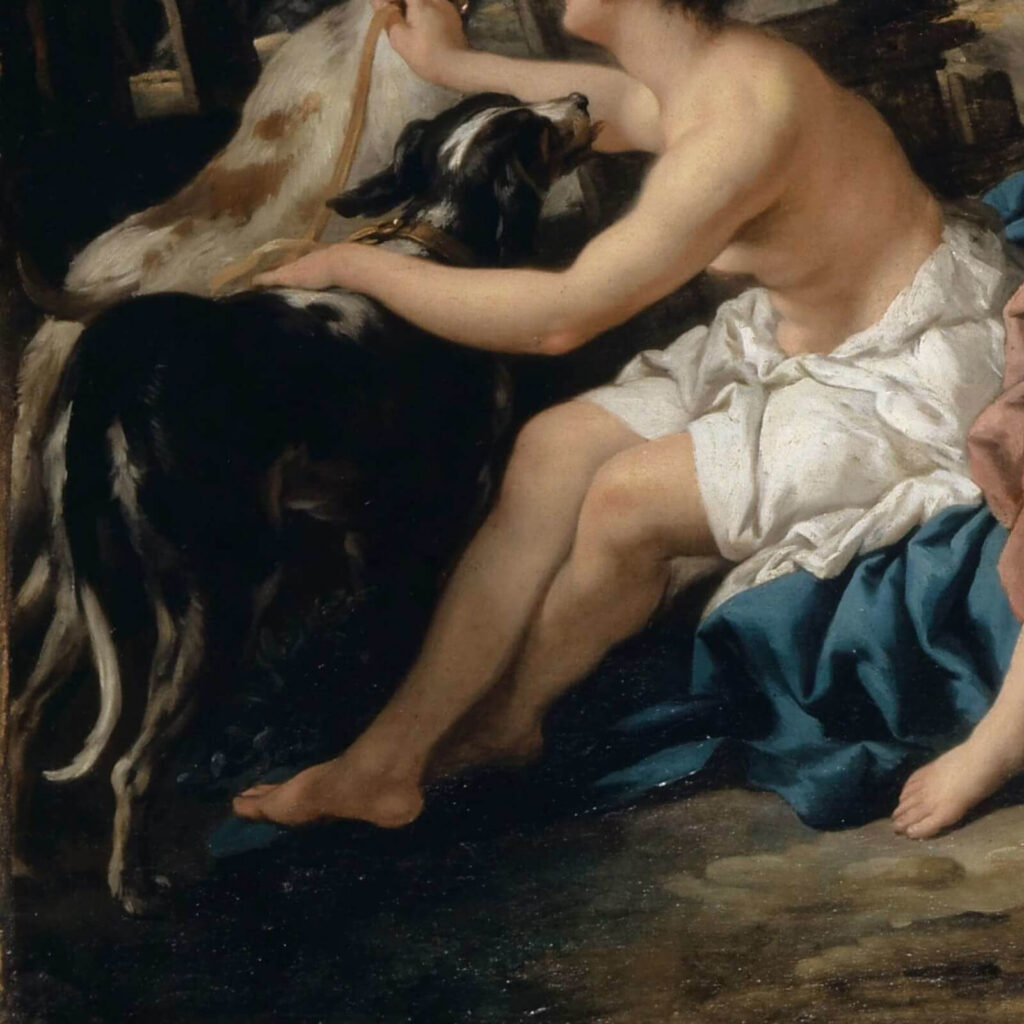

Diana and Actaeon is an oil on canvas measuring 196.2 cm (77.24 in) wide and 130.8 cm (51.50 in) high. It features the goddess Diana in the middle, surrounded by 13 nymph attendants. To the far left is a stag, a male deer, fleeing the female company as it is chased by hunting dogs. All of the female figures are in stages of undress with either shocked or surprised facial expressions. However, who and where is Actaeon as suggested in the title? What is the story of Diana and Actaeon? Jean-François de Troy cleverly and subtly painted an image of Roman mythology that deserves a deeper explanation.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland.

Diana is one of the twelve great Olympian deities. She is the ancient Roman goddess of hunting who is the equivalent to Artemis of ancient Greece. She is the daughter of the chief god Jupiter (Greek Zeus) and the minor goddess Latona (Greek Leto), and she is the fraternal twin of Apollo. Diana is a virginal goddess who is the epitome of athletic, chaste femininity. She shuns masculine company and surrounds herself with an entourage of virginal nymphs who are like court attendants functioning in her daily activities of hunting, bathing, and eating.

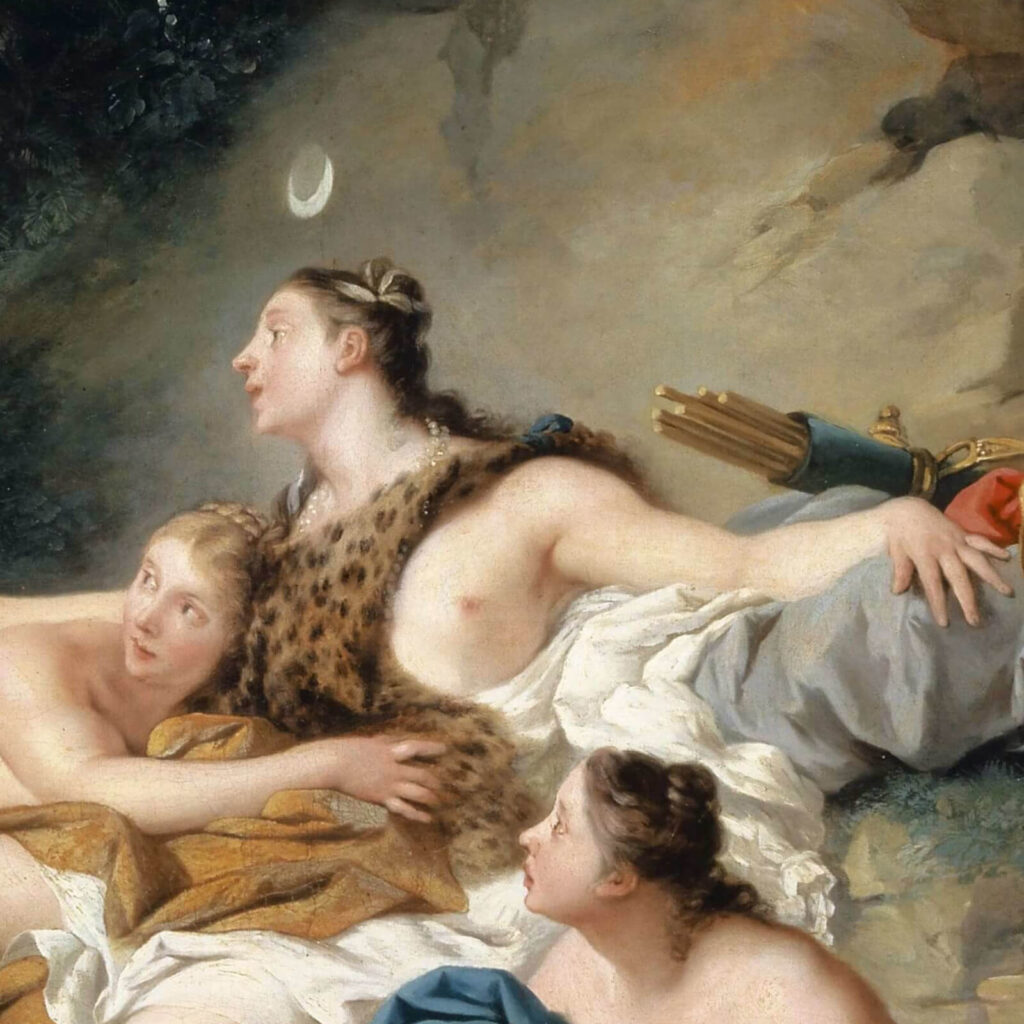

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Within the painting, Diana is the most important figure and is placed in the composition’s center. She is the only figure to wear a leopard skin, to wear a pearl necklace, and to be near a quiver of arrows. Also, a shimmering silver crescent hovering above her head indicates her mythological association with the moon. Diana is clearly the star of the painting. Furthermore, her wide muscular shoulders, thick forearms, and large hands physically separate her from the smaller, thinner, daintier nymphs. Troy shows that while the nymphs may join her on the hunt, only Diana is clearly hunting because only she has the advanced upper-body musculature developed by archery.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Actaeon was the grandson of King Cadmus of Thebes. He was a legendary hunter who was known for his bravery and exploration. However, his fearlessness eventually caused his death. The Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE-17 CE) included Actaeon’s story in Book 3, Lines 138-252 of his Metamorphoses, an epic narrative poem of almost 12,000 lines.

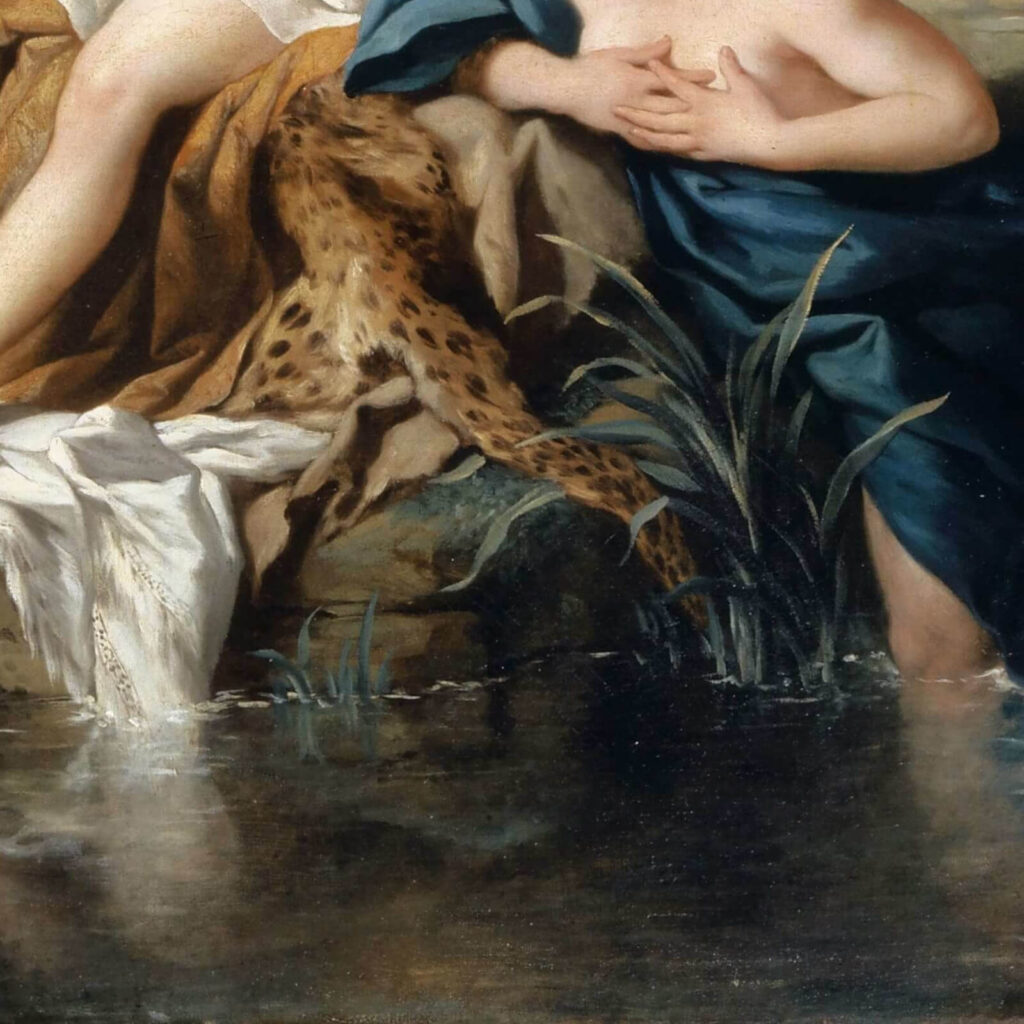

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Actaeon wandered into some woods sacred to the goddess Diana. Unbeknown to him, he then stumbled upon a sacred spring where Diana was bathing with her nymphs after a day’s hunt. Surprising the man-avoiding Diana, he was horrified to see the unclothed goddess. Diana, equally embarrassed but deeply offended that a male mortal should see her divine nakedness, made a fatal judgment. She threw some sacred water upon Actaeon thus transforming him into a deer. Actaeon, now a deer, runs away from the vengeful goddess. However, Actaeon’s fate becomes far worse as his own hunting dogs, not recognizing their transformed owner, chase him, bite him, and eventually kill him. Actaeon, the hunter, becomes the hunted.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Jean-François de Troy, therefore, painted Actaeon after his deer transformation. The scared Actaeon, in the painting’s left, flees the female figures meanwhile four dogs bark and bite at his heels. Hence, the painting Diana and Actaeon displays the final moments of the mythological story. This is also why Actaeon is not to be found as a man in the image.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

The painting is a brilliant visual interpretation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. However, it does not slavishly present an ancient Roman scene. Jean-François de Troy may have used a classical source for subject inspiration but he also infuses early 18th-century French sensibilities. French Rococo is known for its vibrant colors, curvaceous lines, sensual bodies, and idyllic landscapes. Troy combines all four elements into Diana and Actaeon. The painting is a perfect example of a Rococo interpretation of an ancient Roman subject. Two distinct times and cultures blended into a new visual synthesis.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Some art historians believe that Diana and Actaeon is a companion piece to Rape of Proserpina now found in the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. This painting was created one year later in 1735 and has very similar dimensions of 161 cm (63.39 inches) wide by 122.50 cm (48.29 inches) high. Like Diana and Actaeon, it presents another Greco-Roman myth shrouded in Rococo sparkle, however it explores a female victim instead of a male victim.

Jean-François de Troy, Rape of Proserpina, 1735, State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Jean-François de Troy explores the psychology of human reactions through the different facial expressions found in Diana and Actaeon. While Diana reacts to the situation with sang froid (emotionless self-control and presence of mind), her nymphs react in shock, fear, or arousal. The nymphs to Diana’s left are in shock, their mouths and eyes wide open.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Two nymphs in the bottom right corner cower together and fear spreads across their faces and embraced arms.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Just above the fearful two, are three nymphs with curiously aroused expressions. Their eyes look longingly as their hands touch and caress their chests. Everyone in the scene seems to react to Actaeon’s approach and transformation in different ways. There are 14 human figures and 14 shades of emotions.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

Troy recognized that everyone reacts differently to situations and that can serve to intensify the complexity of the works. Viewers may have similar emotions to the figures. Viewers may disagree with the figure’s reactions and think “I would think or react differently.” However, very few observational and thoughtful viewers cannot remain apathetic. Troy sparks some sort of thought or reaction. Isn’t that the basis of great art? Does it not inspire a thought or form a reaction in the viewer? Great art feeds the soul and Troy’s Diana and Actaeon certainly feeds the souls of today’s visitors to the Kunstmuseum in Basel, Switzerland.

Jean-François de Troy, Diana and Actaeon, 1734, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Detail.

“Autoportait.” Collection. Château de Versailles, Versailles, France. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

“Diana und Aktäon.” Collection. Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

Levey, Michael. Painting & Sculpture in France 1700-1789. New Haven, CT, USA: Yale University Press, 1993.

Lodwick, Marcus. Museum Companion: Understanding Western Art. New York, NY, USA: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003.

“Rape of Proserpina.” Collection. State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!