The Women Who Changed Photography: Book Review

Established writer of photography Gemma Padley has created an overview of significant women photographers in her newest book, The Women Who Changed...

Mary Margaret Swets 11 November 2024

Letizia Battaglia was an Italian photographer who gained international recognition for her powerful and poignant documentary work, particularly focused on the brutality and impact of the Sicilian mafia during the late 20th century. Battaglia’s work is not only visually striking but also serves as a form of commentary, shedding light on the realities of organized crime and its harms to society.

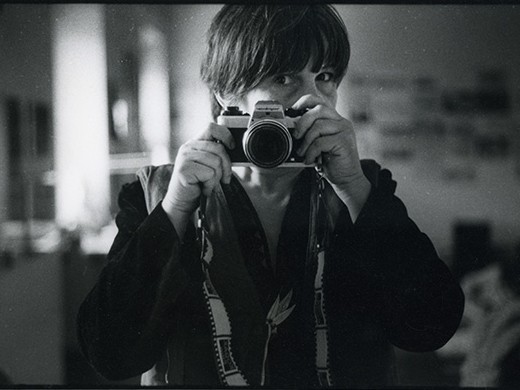

Letizia Battaglia, Self-Portrait, 1990s, Letizia Battaglia Archive.

Letizia Battaglia (1935-2022) began her career in 1969 with the Palermo newspaper L’Ora. After moving to Milan in 1970 to photograph for other publications, Battaglia returned in 1974 to Palermo and co-founded with Franco Zecchin the agency Informazione Fotografica, which was frequented by renowned photographers such as Josef Koudelka and Ferdinando Scianna.

Over the Years of Lead, a tumultuous era marked by political unrest and social turmoil in Italy, Battaglia documented mafia crimes and exposed their atrocities. However, as one of the few working female photojournalists, Battaglia initially got some pushback from law enforcement authorities. Boris Giuliano (1930-1979), the local police chief, was the first supporter of her endeavors.

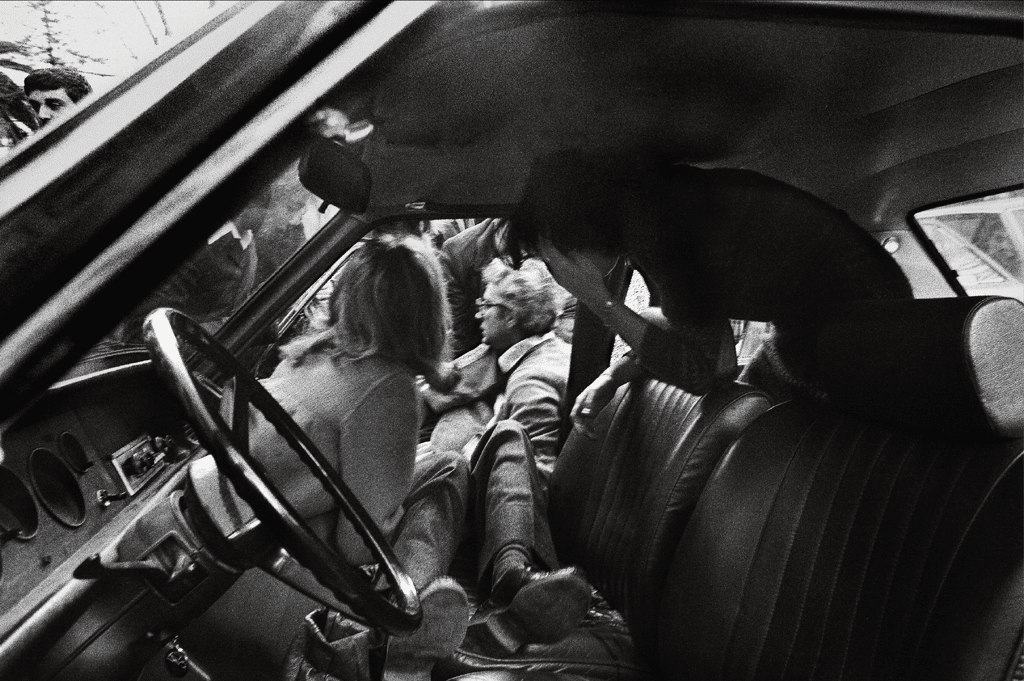

Letizia Battaglia, The President of the Sicilian Region, Piersanti Mattarella, has just been fatally shot by mafia killers, Palermo, 1980, Letizia Battaglia Archive.

Battaglia stands as a beacon of courage in the realm of photojournalism, particularly for her unwavering dedication to revealing the sinister underworld of the Sicilian mafia. Through her lens, she captured the raw essence of organized crime, exposing its brutality with unflinching honesty.

This is when Piersanti Mattarella (1935-1980), an Italian politician and President of the Sicilian Region, has just been shot. The scene is poignant: Mattarella’s body is being dragged out of the car while in the left corner of the picture, a woman hunches over in grief. Battaglia framed the scene in a composition reminiscent of a Caravaggio painting and foregrounded the anguish to the full. From just the sight of it, we seem to hear voices and feel the terror of the spectators as they congregate around the car.

It was a wonderful holiday. […] We had gone to celebrate with our friends […] and as we passed by, I saw this small crowd of people. […] We thought it was an accident. But Franco stopped the car, and shortly after, they told us it was Mattarella. So, through the broken window, I took a shot from inside. I had the scene there; I couldn’t waste time.

La Repubblica, 2021.

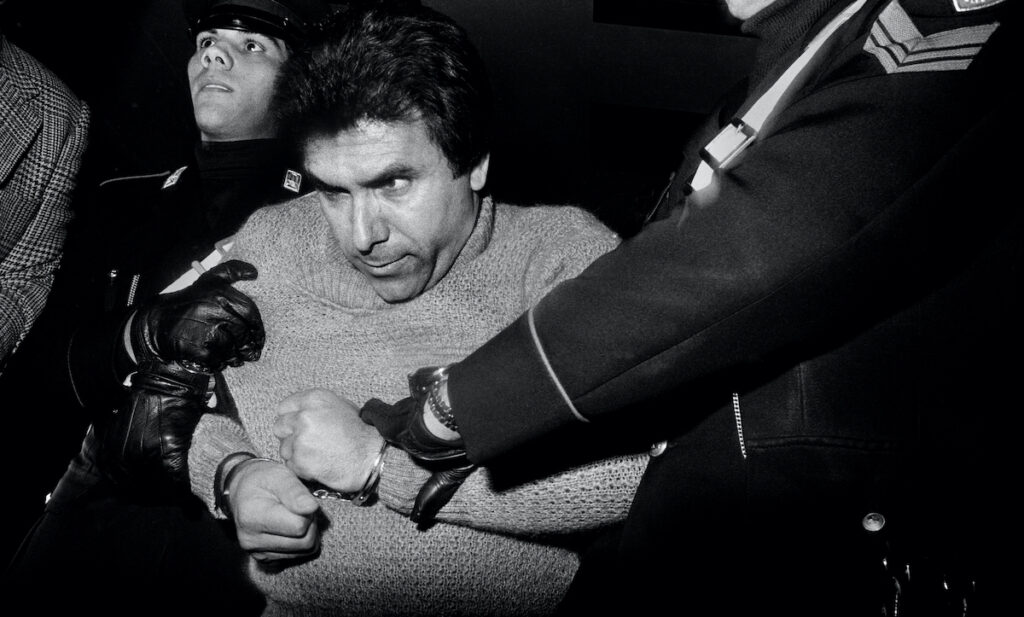

Letizia Battaglia, The arrest of the boss Leoluca Bagarella, Palermo, 1980, Letizia Battaglia Archive.

Images of mafia members, such as Leoluca Bagarella (1942-), offer a chilling glimpse into the faces that perpetuated violence and corruption in Sicily. Bagarella, imprisoned for multiple murders and involved in numerous terrorist attacks causing the loss of many lives, is the quintessential embodiment of evil. Few would dare to approach him, yet Battaglia’s work transcends mere documentation; it testifies to the power of photography as a tool for social change. By exposing the harsh realities of mafia violence and the brutal individuals behind it, she shines a light on the urgent need for societal reform and collective action against organized crime.

The police had the habit of taking the arrestees out and having them photographed. When he came out and saw a woman in front of him, he went crazy. He kicked me […] I threw myself backward and fell, but in the meantime, I had already taken the photo. […] We looked at each other, my goodness.

La Repubblica, 2021.

Giovanni Falcone (1939-1992), an Italian judge and prosecuting magistrate, dedicated his life to combating the influence of the Sicilian mafia in parallel with his friend and judge, Paolo Borsellino (1940-1992). Their career reached a zenith during the Maxi Trial held from 1986 to 1987. Tragically, on May 23, 1992, Falcone, along with his wife, magistrate Francesca Morvillo, and three members of their escort, was assassinated in the Capaci bombing, with 23 others injured.

I was by my mother. […] and on television they said: ‘A car has exploded on the highway, it seems to be judge Falcone.’ I didn’t go. I loved judge Falcone so much. […] He was a wonderful person, kind, shy. He loved Palermo, he loved justice. I didn’t want to see him dead.

La Repubblica, 2021.

After less than two months, on July 19, 1992, Borsellino was killed by a car bomb near his mother’s house in Palermo.

It was almost two months of torment, of pain. And the last time we met Borsellino, our hearts were shattered. He had that desperate look on his face. He knew they would kill him. […] When they killed him, I went, but I didn’t raise the camera. […] there was only Borsellino’s belly, I couldn’t photograph him. I didn’t photograph anything. I didn’t photograph anymore.

La Repubblica, 2021.

In her shots of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, Battaglia immortalizes the faces of justice in a battle against seemingly insurmountable odds. These photographs not only serve as a tribute to their courage but also as a reminder of the immense sacrifices made in the pursuit of truth and justice.

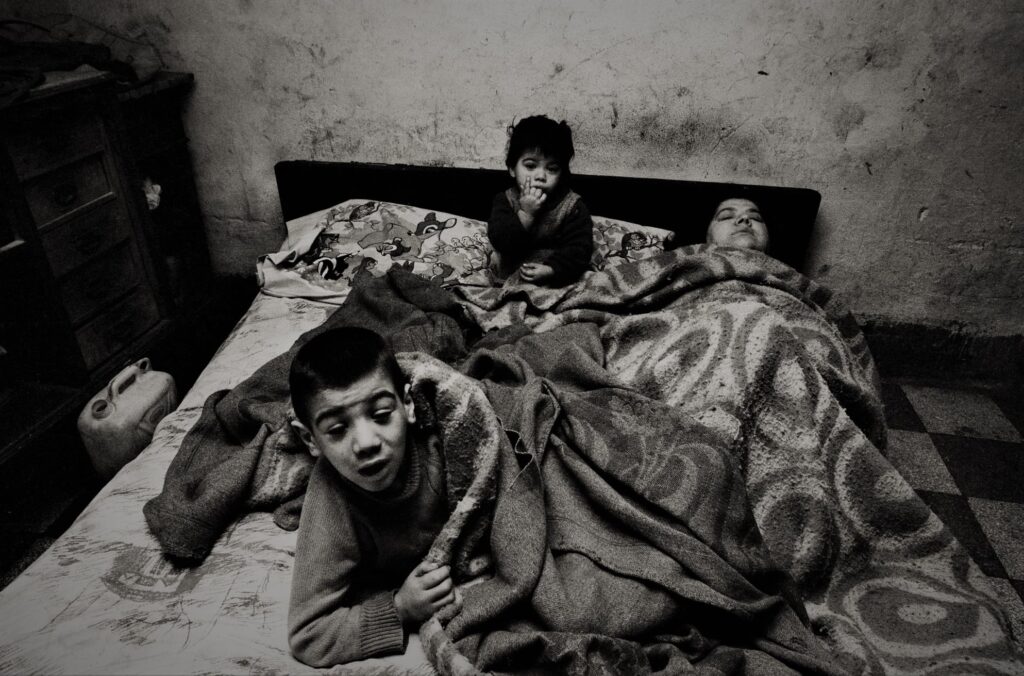

Letizia Battaglia, This woman and her children are always in bed; there’s neither electricity nor water in the house, Palermo, 1978, Letizia Battaglia Archive. iItaly.

Battaglia is not solely a mafia photographer, even though she gained international acclaim for her contribution to this field. Her vivid black-and-white photos depict Palermo in all its complexity—She captured its streets and traditions, children, women, and victims of the mafia as much as she paid attention to the grief and daily life of the locals, as well as the faces of power in a city of contradictions.

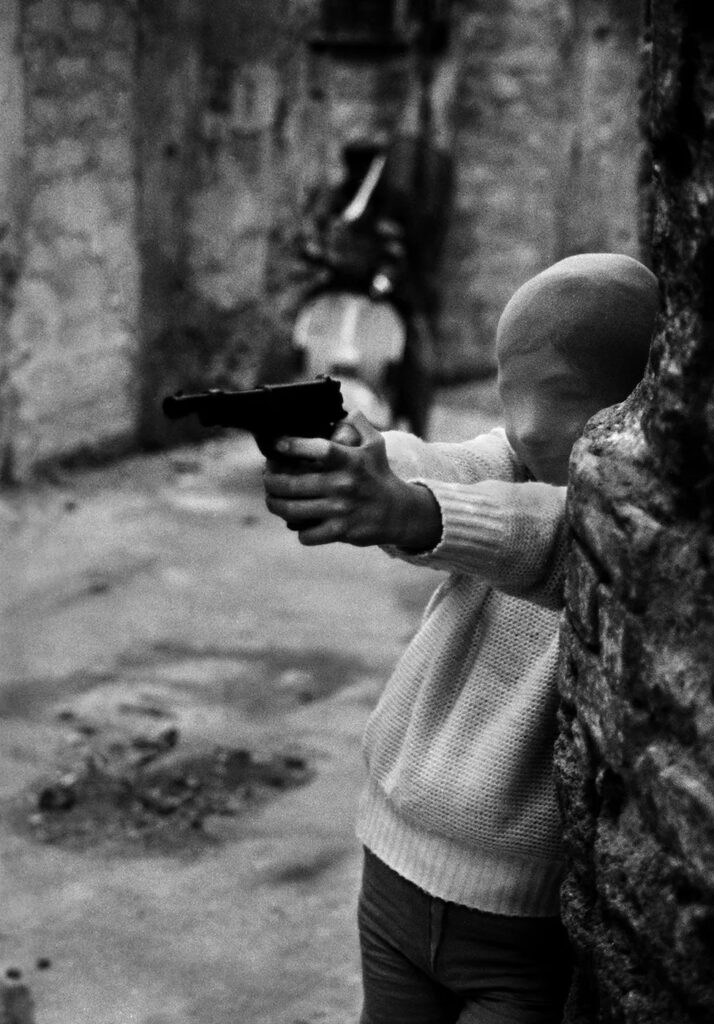

Letizia Battaglia, The killers’ game, near the Church of Santa Chiara, Palermo, 1982, Letizia Battaglia Archive. Corriere della Sera.

Throughout her career, Battaglia showed a keen interest in depicting the lives of the city’s children. She offered an intimate glimpse into moments of spontaneity and authenticity among Palermo’s younger generations amidst the challenging urban realities.

Letizia Battaglia, Near the Church of Casa Professa, Palermo, 1991, Letizia Battaglia Archive.

These compassionate portraits of Palermo’s children celebrate youth while expressing the innocence, joy, and resilience associated with her subjects. The invigorated faces captured still serve as poignant reminders of the many facets of Palermo.

Letizia Battaglia, Woman smoking, Catania, 1984, Letizia Battaglia Archive.

On the other hand, Battaglia’s photographs of women offer a multitude of depictions of femininity and explore how the latter could imply both sensitivity and strength in the context of Sicilian society. The women she photographed in Palermo take up different roles and embody various experiences and emotions, but all of them were in direct conversation with the challenges they face as fellow human beings in search of empowerment.

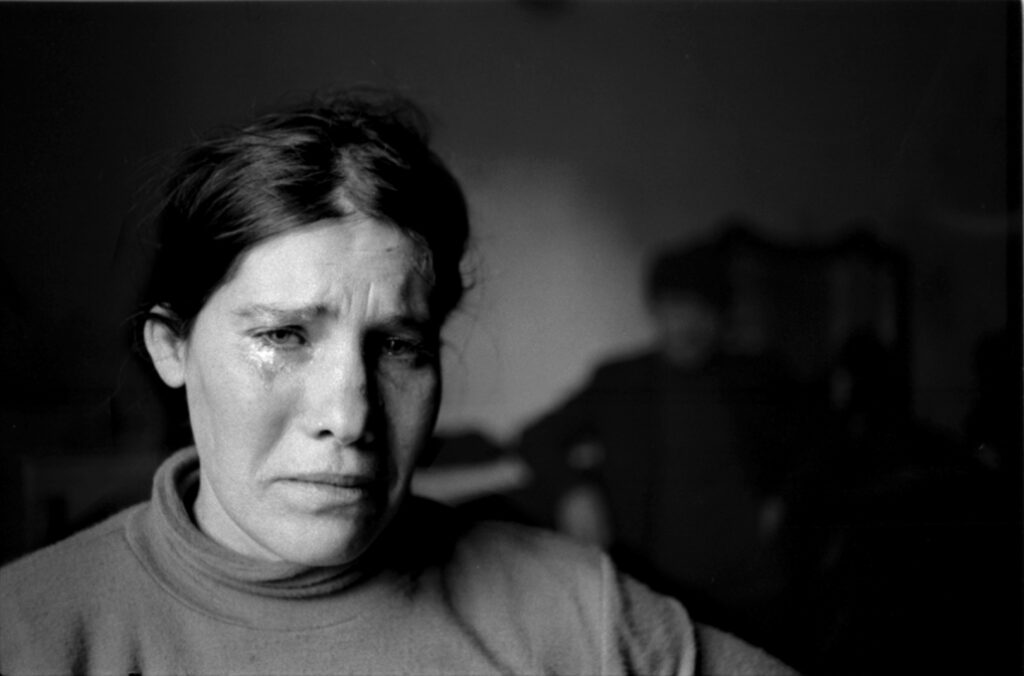

Letizia Battaglia, A woman crying over her misery, San Vito Lo Capo, Trapani, 1980, Letizia Battaglia Archive.

Whether they are mothers, workers, or survivors, the women in Battaglia’s photographs always convey with their body language a sense of resilience and determination. Such a creative approach to femininity enabled Battaglia to demonstrate how life in Sicily was about resisting societal norms, persevering under economic hardships, and weathering the crippling repercussions of organized crime.

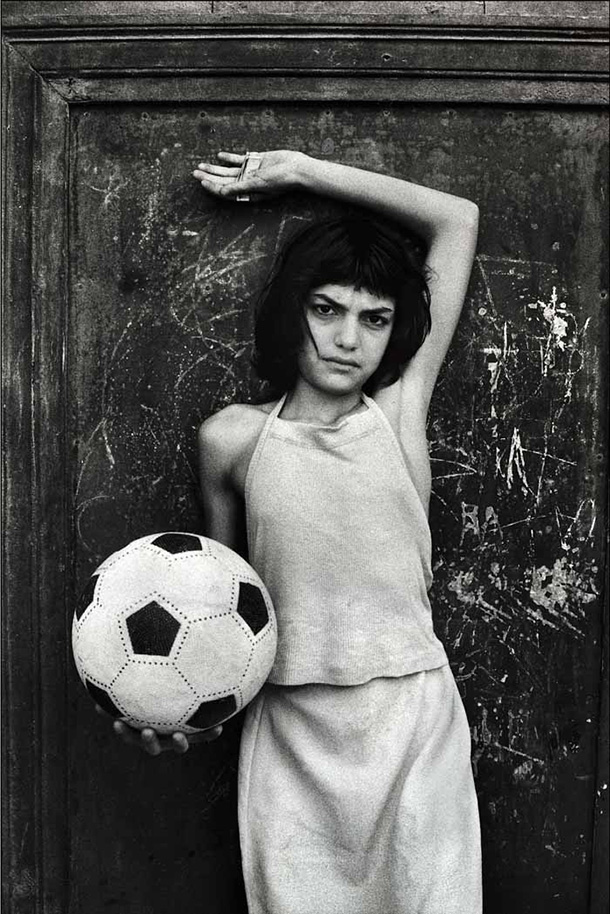

Letizia Battaglia, The girl with the ball, La Cala district, Palermo, 1980, Letizia Battaglia Archive.

In this photograph, a young girl is holding a ball. She gazes at the camera with a mixture of curiosity and apprehension. The simplicity of the scene belies the deeper layers of meaning conveyed by Battaglia’s composition and framing. At first glance, the image may appear to document a fleeting moment of childhood play. However, upon closer examination, the viewer is confronted with the stark realities of life in Palermo. The girl’s surroundings are dilapidated; crumbling walls and graffiti-covered surfaces complement her solitude. Yet the girl seems to show no fear. Her posture and expression suggest she will tackle adversity head-on and with courage and grace.

Letizia Battaglia, At Arenella Beach, The Party is Over, Palermo 1986, Letizia Battaglia Archive.

The photos remain, but it would have been better if the state had defeated the mafia. It didn’t happen that way. The state didn’t want to win. […] The mafia is still here, the mafia controls our lives, our money […] I won’t see the end of it.

La Repubblica, 2021.

In the 1980s, Battaglia established the Laboratorio d’If, where she mentored Palermo’s photographers and photojournalists. In 1985, she became the first European woman to receive the Eugene Smith Award in New York, alongside American Donna Ferrato. She also received the Mother Johnson Achievement for Life in 1999.

Battaglia exhibited her work worldwide. Her social commitment and passion for freedom and justice are narrated in the monograph Passione, giustizia, libertà (Passion, Justice, Freedom). From 2000 to 2003, she co-edited the bi-monthly magazine Mezzocielo founded in 1991. Disillusioned by social changes and feelings of marginalization, Battaglia moved to Paris in 2003, only to return to Palermo in 2005. In 2008, she made a cameo appearance in Wim Wenders’ film Palermo Shooting.

Many photos taken by Letizia Battaglia were used in the documentary film In un Altro Paese (In Another Land) directed by Marco Turco. The film examines the tensions between the Sicilian mafia and the Italian government during the years of the First Republic. It records a glorious fight against the mafia focusing on the largest anti-mafia trial ever held in Palermo or the Maxi Trial and magistrates Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino who made it possible.

Shooting the Mafia, directed by Kim Longinotto, is another riveting documentary that illuminates the life and work of Letizia Battaglia. Through a fascinating blend of archival footage, interviews, and Battaglia’s own striking photographs, the film explores her journey to becoming a celebrated photojournalist, with profound insights that shed light on her unique perspective, personal sacrifices, and unwavering commitment to truth and justice.

Letizia Battaglia, Goffredo Fofi, Volare alto volare basso, Roberto Koch Editore, 2021.

“Letizia Battaglia: A dieci anni ho incontrato un orco, da allora ho l’ossessione delle bambine,” Interview by Giulia Santerini, La Repubblica, 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!