Mikhail Mansion—From Military Into Interactive Art

Mikhail Mansion is an artist and engineer who blends digital and mechanical elements to create interactive experiences that foster connections...

Agnieszka Cichocka 26 April 2024

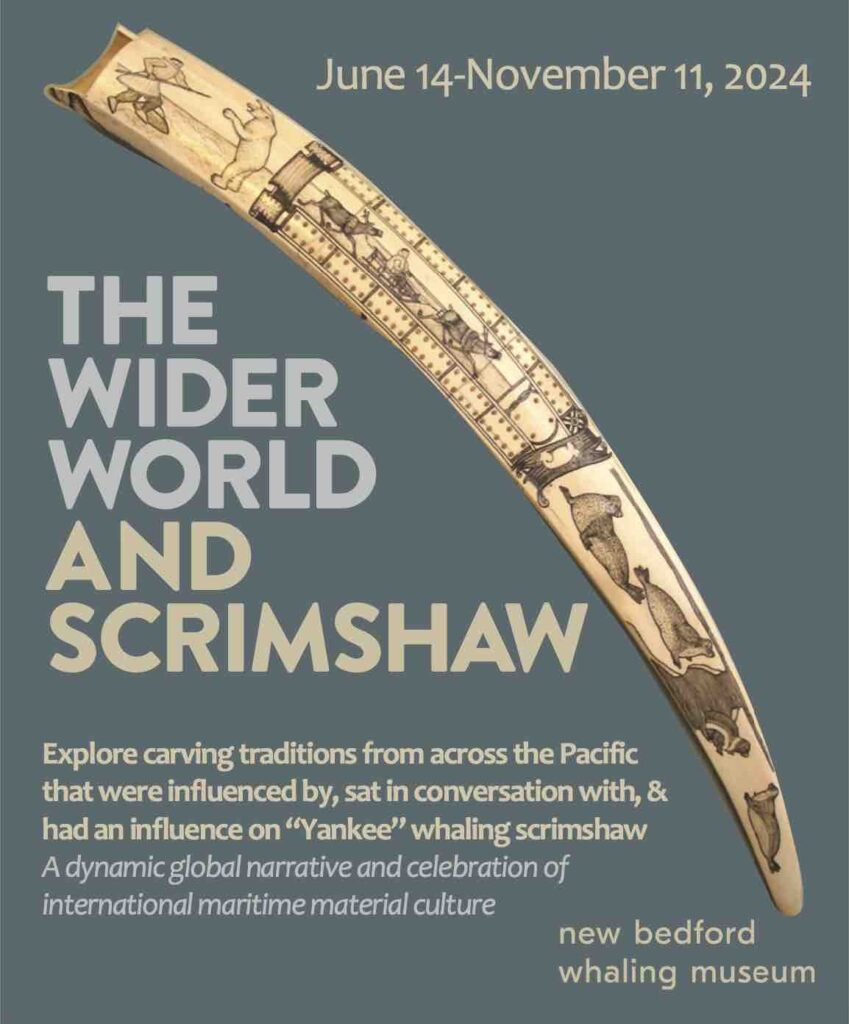

We had to take a moment to share a brilliant and challenging exhibition at New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts, USA. The Wider World and Scrimshaw runs until November 11, 2024. Home to the world’s most extensive collection of scrimshaw, the New Bedford Whaling Museum (NBWM) has started a fascinating conversation about the place of scrimshaw in art history. These artifacts are objects carved by whalers as the by-products of marine mammals.

Maker once known (Iñupiat, possibly Port Clarence mission school), Iñupiaq men holding cultural belongings, c. 1890s. New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

Traditionally, scrimshaw is considered a rare and esoteric 19th-century British and American art form or a workers’ craft. But in this exhibition, scrimshaw is placed firmly within a global community of carvers from the earliest sea-faring times to today. It seizes the opportunity to retell the history of how sea creatures, indigenous cultures, and immigrant settlers interacted.

DailyArt writer Candy Bedworth managed to grab a moment with NBWM Chief Curator Naomi Slipp to discuss why The Wider World and Scrimshaw is a must-see exhibition.

Maker once known, Ditty box, c. 1860, red cedar, whale skeletal bone, green abalone, and mother of pearl, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

Candy Bedworth: What will we see in the exhibition?

Naomi Slipp: The Wider World & Scrimshaw takes the NBWM scrimshaw collection and places it in conversation with carved decorative arts and material culture made by Indigenous community members from across the Pacific and Arctic. We are showcasing over 300 objects. We have scrimshaw from Alaskan, Azorean, New England, Māori, and Australian Aboriginal makers.

There are over 40 examples of carved sperm whale teeth, an iconic scrimshander art. And we have an incredibly rare print of Lahaina as seen from Lahainaluna, a copperplate engraving from a painting by Persis Goodale Thurston Taylor.

Kepohoni, Lahaina as seen from Lahainaluna, c. 1840, copperplate engraving from a painting by Persis Goodale Thurston, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: What message do you want visitors to go away with after they see this exhibition?

NS: At its core, we hope it will help give people a diverse sense of the connections between people and their environment in the Pacific world. The focus of our collection is American whaling ventures, but we seek to demonstrate how whales and other marine mammals are a vital part of the life of communities within the circumpolar North and the Pacific.

We know that those relationships had much deeper and longer timelines than the 50-year period when American whalers were arriving, depleting the oceans, and then going on their way. We have a deep investment in showing people the wider picture.

Maker once known (Niue), Hiapo, 1880–1890, handmade bark cloth, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: I see that you have invited contemporary artists to contribute.

NS: Yes! We have 12 contemporary artists included in the exhibition, responding to ancient artifacts. We have Hiapo (decorated bark cloth) makers from Hawaii and Nuie. Modern artists are renewing or reviving old traditions and practices. Multi-media artist Courtney M Leonard has an accompanying exhibition called BREACH: Logbook 24 Scrimshaw at our Center Street Gallery.

BREACH explores the historical and contemporary ties between place, community, whales, and the maritime environment. Courtney M Leonard is a member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation, and BREACH is her largest body of work to date, investigating narratives of Indigenous food sovereignty, marine life, and human environmental impact.

Courtney Leonard, BREACH #2 (part of a limited series, started in 2015, marking the death of one whale), Ceramic sperm whale teeth and wooden pallet, image courtesy of the artist, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: I love your use of the phrase “maker once known” rather than “anonymous” or “unknown.” It is a kinder and more inclusive language. And also, you specifically recognize “culture bearers” (Indigenous people who consciously embody their culture and ancestry and share it).

NS: Yes, our work is respectful, interdisciplinary, and community-driven. We try to be careful in how we present materials, using not just curatorial voices, but also contemporary voices, of scholars, culture bearers, and artists. We hope that in that one simple act of hearing different voices, people will realize there are different ways of looking at and approaching these artifacts.

We invite people to enjoy looking at the museum artifacts and to take pleasure in them. But at the same time, audiences can dig a little deeper and think critically about American history.

Duke Riley, No. 384 of the Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum, painted salvage plastic, ink and wax, 2023, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: I enjoy the confrontational humor in the work of artist Duke Riley. The New York Times calls him “Grand Master Trash”. He has spent time decorating discarded plastic “trash” with traditional scrimshaw images. Do you have his work in the museum?

NS: Yes, We have his piece about the industrial history of New Bedford and the major industrial polluters who dumped waste in the waters off the coast of New Bedford.

Maker once known, Coconut dipper, c. 1850, coconut shell, pewter, wood, and walrus ivory, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: I suppose we have to address the age-old question of art vs craft. Is scrimshaw fine art? Or folk art? Or is it a craft?

NS: I am a cultural historian. I am trained as an art historian, but I think that things made by people tell us a lot. Whether someone defines a work as fine art or not depends a lot more on the social and political structures that existed at any given moment than on the art itself.

Attributed to John Ootuck (Yup’ik), Mutt and Jeff, 1907–1925, bone, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: What is your favorite piece of work in the exhibition? What are you most excited about?

NS: One of the pieces that kicked off this project is a small, unassuming, chipped baleen busk (baleen are bristly plates found in the jaws of large whales, used to filter krill and plankton from the water. A busk is a long, flat slice of baleen or a slice of whale rib). It looks like a little bookmark bearing dark, scratchy designs. We were examining the designs, and someone suggested that it looked like a navigation chart.

Questions arose about what kinds of assumptions we make about makers of material culture like that, about who they are, and what experiences they bring. These people might be on a three to five-year journey at sea, meeting other communities and makers. We don’t think about the 19th century as a global world, but it was! At a certain point, 20-30% of American whaling crews could be Pacific islanders. That tiny piece certainly started quite a conversation.

Art Thompson (b. 1938; Nuu-chah-nulth), Tackle Box, 1992. Cedar, leather and paint, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: And from that small carved baleen artifact, how long did it take to get to the exhibition opening?

NS: Perhaps two and a half years of project time. Initially, we explored the shape of the project and identified what the core questions and focus of the exhibition should be. The plan crystallized through conversations with a diverse advisory board who helped give us direction. It was exciting to have around 30 people collaborating on the project, their experience and culture was so rich and wonderful.

Installation photo from BREACH: Logbook23 | CORIOLIS at the West Carolina University Fine Art Museum at the Bardo Arts Center, Cullowhee, North Carolina, 2022, image courtesy of the artist.

CB: Are you including audio materials such as oral recordings or music in the exhibition? Will there be items to handle?

NS: Great question! We will have all of the above! We have recordings of traditional community stories about whales. A whaler will talk about his experiences on the hunt from a native perspective. There will be interviews with contemporary carvers. And also video clips, animations, and touch screens.

We can’t just hand out ancient bones and teeth, but there is so much that is tactile in the exhibition, that you want to reach out and touch them! So, we have commissioned a ceramicist to create six sculptural ‘in-the-round’ plaques that can be touched. And we have a case of materials from our education collection containing items like baleen and a sperm whale tooth.

Chief Curator Naomi Slipp in front of Alison Wells, Beyond the Shadows. Photo by Don Wilkinson, The New Bedford Light, 2024.

CB: You speak so enthusiastically about your work. What was your route into museum work?

CS: I’ve always liked material culture, and finding out about local and regional history. At high school, aged around 16, I spent some time as a docent at a local historic house museum, where I loved giving tours and sharing stories. Drawn to art at school, I went on the study art history, and now here I am back in Massachusetts!

New Bedford Whaling Museum, aerial view. Photo from NBWM website.

CB: Apart from NBWM (of course!), what is your favorite museum to visit?

NS: There are museums doing wonderful things, but I have a soft spot for those quirky institutions that maintain an eclectic collector vibe. For instance, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, MA, USA, or the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, UK.

My real love and passion from a scholarly perspective is the intersection between art and science in the 1800s. I am fascinated by how disciplines shape knowledge and how they share that with the public. For example, the Hunterian Museum in London taught people to look at medicine and surgery in a particular way. Museums tell stories that shape our ideas; how we looked at things in the past shapes how we view them today.

Australian aboriginal maker once known, Dream tooth, c. 1850, sperm whale tooth, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: And what does the future hold for you and the NBWM?

NS: We will continue to explore the legacy of ethnographic collections, looking at what was collected, what was displayed, and how. We have much left to do.

There are so many art pieces waiting to be researched, displayed, and received their dues. This scrimshaw project is ongoing. This exhibition is opening the door to a much bigger stage—to work that will continue for decades. Connections have been made that will continue, learning will be ongoing, and it’s an investment in the collection.

Maker once known (Niue), Hiapo, 1880-1890. Handmade bark cloth, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

Candy: A local newspaper reviewer, Don Wilkinson, said that you have outstanding, thought-provoking exhibitions and are “as hip as could be”! How do you feel about that?

NS: (laughing) Not bad! I won’t refute that! Don is very kind! Museums evolve and are shaped by their teams. We have an amazing Director and an incredible team of curators bringing ideas and focus. If people are seeing the change we are trying to make, that is great.

The Wider World and Scrimshaw Prospectus, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, USA.

CB: Thank you so much for a fascinating insight into your work and your exhibition. Do you have any final words for our readers?

NS: For anyone who cannot visit us in person, there will be free virtual programs that might interest folks. We are planning Zoom conversations involving staff, artists, scholars, culture bearers, and community experts. Maybe we’ll tackle that art vs craft question head-on! And there is an exhibition catalog coming in the summer, with contributions from over 40 people, including our advisory board, our partners, and artists – we’re excited about that! These will be available via our website.

The Wider World and Scrimshaw runs through November 11, 2024, at New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, US.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!