Hunting for Northern Lights: Aurora Borealis in Art

With mesmerizing colors dancing in the night sky, witnessing an aurora must feel like being inside of a painting. What are the northern lights and...

Marta Wiktoria Bryll 20 January 2025

7 August 2022 min Read

Today, Seville’s golden age may have passed, but that is not to say it is without its treasures. Now the capital of Andalusia has inherited a rich architectural heritage over its long and multicultural history. Indeed, walking down the narrow streets or along the bank of the river, one can still see the sites where Islam met and mixed with Christianity.

Although founded as the Roman city of Hispalis, Seville was absorbed into the Visigothic Kingdom after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century. In 711, the city once again changed hands as it was conquered by Moorish invaders of the expanding Umayyad Caliphate. Nevertheless, it returned to Christian rule in 1248 after being reconquered by Ferdinand III of Castile. When gold was discovered in the Americas, Seville was granted a monopoly for stockpiling and trading New World goods before they were distributed to the rest of Spain, as its location 80 kilometres up the Guadalquivir River offered a safer location than any seaside port.

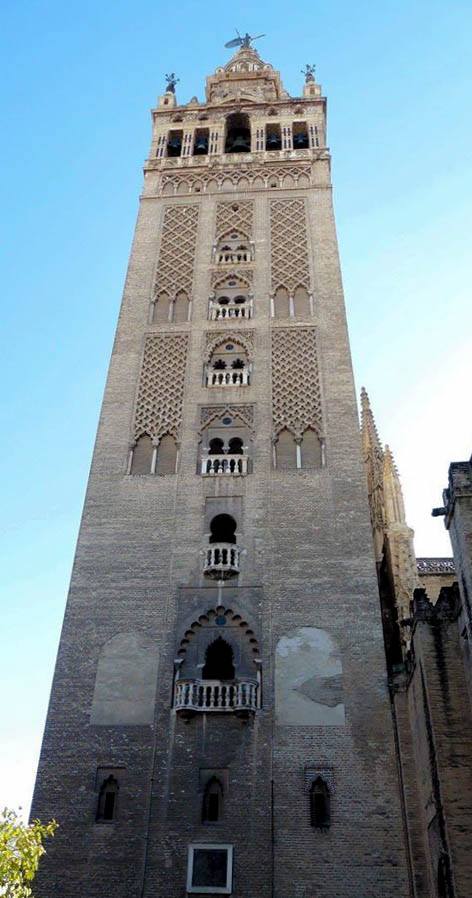

The site of the current Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See was originally the location of a grand mosque constructed under the Almohad caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf. Completed in 1198, it was notable for its giant minaret, the Giralda, modelled after that of the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakesh, Morocco. Nonetheless, after Seville was reconquered by the Christians, the mosque was gradually converted into a church. It was not until the beginning of the 15th century that city leaders decided to tear down the converted mosque in order to rebuild a Gothic cathedral.

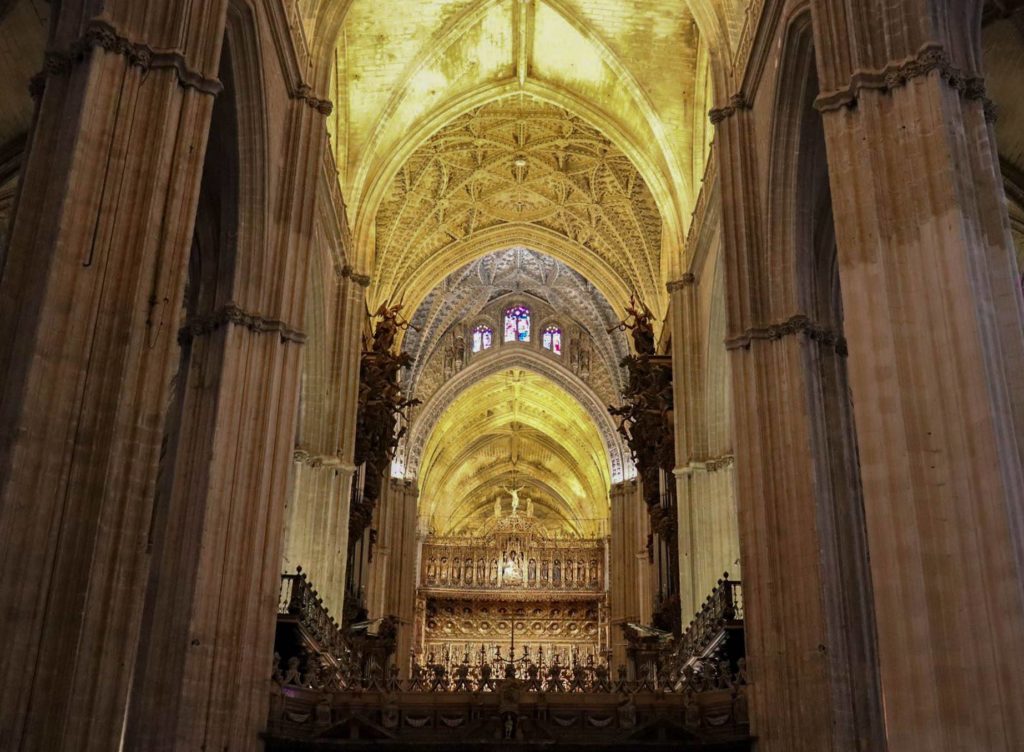

The new Cathedral, completed in 1528, was one of gigantic proportions. Covering a surface area of 23,500 square meters, it is currently the largest Gothic cathedral and the third largest church in the world, after St. Peter’s Basilica and the Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Aparecida. Today, all that remains of the original mosque is the Giralda minaret, which was converted into the Cathedral’s bell tower during its construction. At 96 meters in height, it is Seville’s tallest building. In fact, it is very likely to remain so in the future, as the city’s building codes prohibit the construction of any structures that would exceed its height.

Inside, the long nave is lined by towering pillars and covered by tremendous domes, the tallest of which rises to a height of 42 meters. Looking down the nave, the main altar is largely blocked by the central choir loft. Nevertheless, the upper half of the altar, which measures 30 meters tall, is still clearly visible. Apart from the main nave, the cathedral houses 80 different chapels as well as the tombs of some of the most important figures in Spanish history, not least of whom are Ferdinand III of Castile and Christopher Colombus.

Seville’s Alcázar was originally built as a Moorish fortress, and the name itself is derived from the Arabic word al-qaṣr, meaning “a castle”. However, since the Reconquista, much of the original construction was modified or expanded to fit the tastes of Spain’s monarchs as the palace was passed down from one royal family to another. Today, the Alcázar of Seville is the oldest royal palace still in use in Europe.

Just as the Patio of the Lions is among the most recognizable parts in the Alhambra, the same can be said of the Patio of the Maidens in the Alcázar of Seville. In fact, despite the lower level’s Moorish architectural appearance, it was actually constructed under the rule of Peter of Castile in the 14th century. A close friend of his counterpart Muhammad V, the Sultan of Granada, King Peter ordered the arches of his courtyard to be built in the stalactite mocárabe style with the same rhomboid sebka designs as could be found adorning the courtyards of the Nasrid palaces in the Alhambra. The upper story, however, was added by King Charles V in the 16th century according to the contemporary Italian Renaissance style.

Also dating back to the 14th century is the Ambassadors Reception Room. Despite having this function in later years, it was originally constructed by Peter of Castile to serve as his throne room. Similarly designed in Moorish fashion, the room is yet another example of the king’s taste for Islamic architecture. Nonetheless, clear variations exist between the decoration used here and the one used in his Patio of the Maidens. Namely, the entrances are designed as smooth horseshoe arches instead of the mocárabe arches found outside, and much of the marble is directly painted instead of being covered in ornate plasterwork.

Perhaps the most impressive part of the room, however, is its ceiling, a great wooden cupola adorned with gilded stars and other geometric patterns. When illuminated, the bright patterns in the dark wood give the impression of looking up into a starry night sky. It was exactly under such a “sky” that King Charles V married Isabella of Portugal in 1526.

Although it remained popular in the 14th and 15th centuries, Moorish architecture went out of style in Spain after the end of the Reconquista. From then on, Spain largely followed contemporary European architectural trends, shifting from the Gothic to the Renaissance, and later to the Baroque style of construction and design. It was not until the turn of the 20th century that Spanish architects would begin to revisit the oriental influences in their country’s cultural heritage.

The Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 did much to put Seville back on the map as a global city. To prepare the location of the world’s fair, local architect Aníbal González was commissioned with the construction of the Plaza de España on the edge of the city’s Maria Luisa Park. His project was a massive semi-circular building that would wrap halfway around the plaza until meeting the edge of the park on the other side. The building’s design is an eclectic mix of Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Baroque, and Neo-Moorish styles with local azulejos (glazed ceramic tiles) decorating the façades and towers.

Although also visible in the Plaza de España, no other building constructed for the world’s fair contained more Neo-Moorish elements than the Mudéjar Pavilion did. Also designed by González, the building’s red brick façade with minaret-like towers and arched entrances pay homage to the Moorish style that had once dominated Andalusia’s architectural tradition for seven centuries. Indeed, the abundant presence of Neo-Moorish structures tucked away in the lush gardens of Maria Luisa Park makes even a brief stroll feel like a journey back in time.

The works of González for the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 inspired other local architects to revisit Seville’s Moorish heritage. Today, visitors of the city can enjoy Seville’s eclectic blend of architecture just by walking down one of its main streets, the Avenida de la Constitución. Beginning in Puerta Jerez and walking in the direction of Plaza Nueva, one will pass the Moorish Alcázar, the Gothic cathedral, as well as the large Renaissance structure that houses the General Archive of the Indies.

Continuing past Baroque Iglesia del Sagrario, an eye-catching Neo-Moorish building appears on the left-hand side. The Edificio la Adriática, constructed by José Espiau y Muñoz between 1914 and 1922, gives the passerby a sense that he or she has walked through all the eras of the city’s development and returned full circle to its Moorish roots. At this point, one is faced with a dilemma: to continue towards Plaza Nueva for a sight of the city’s town hall or to take a detour down one of the charming narrow side streets to see what hidden treasures can be found. Luckily, no matter the decision, one thing is certain… Seville will not disappoint.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!