Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

27 October 2024 min Read

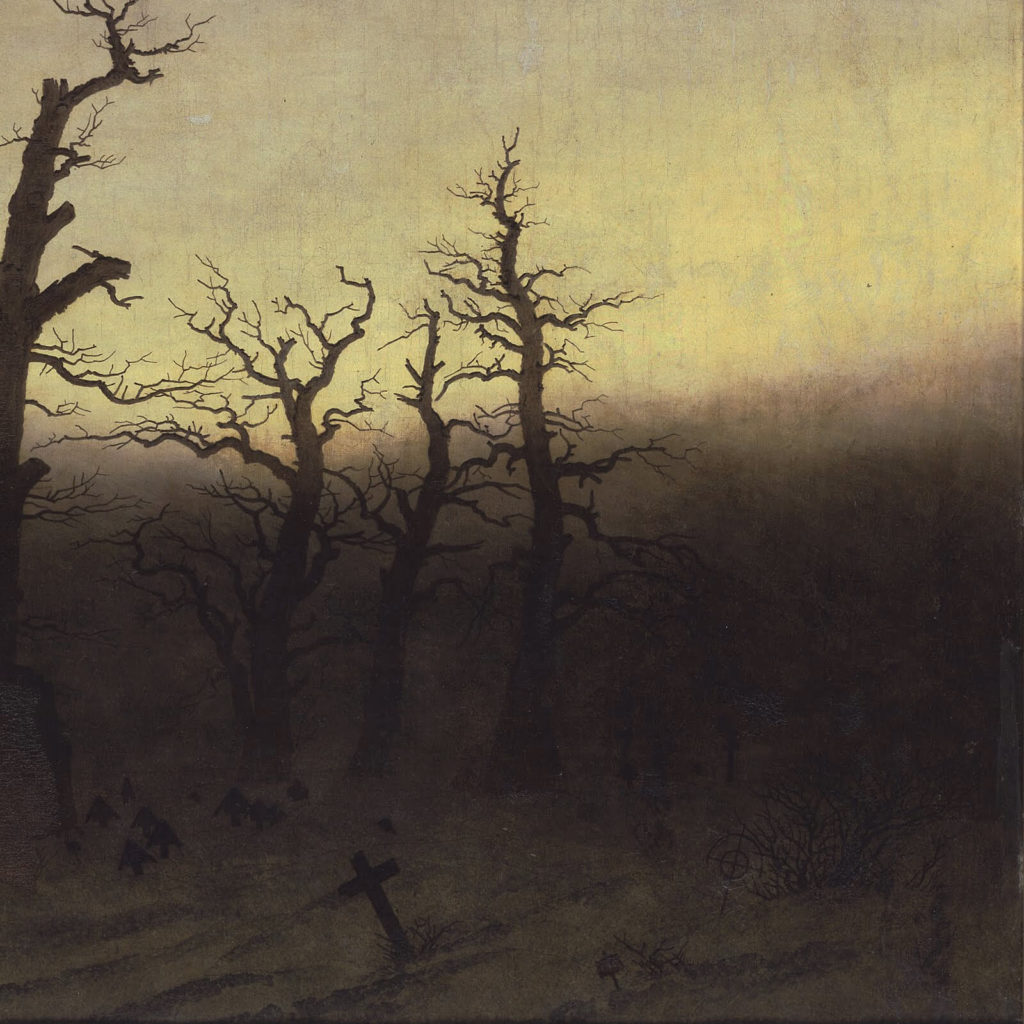

Sadness and desolation fill this scene like an oppressive melancholy. The sun is dying behind the horizon as fog enshrouds the ground. Skeletal trees rise above the mist and surround the crumbling ruins of a Gothic abbey. Silence pervades the air, and a solemn funeral procession crosses over the crunching snow. Monks in black habits carry a heavy coffin deep into the ruined abbey’s interior. A sense of awe and terror overcomes the wintry landscape. Abbey in the Oakwood captures the many sublime themes that are a part of Romanticism. It is truly a macabre masterpiece.

Caspar David Friedrich started painting Abbey in the Oakwood in 1809 and finished it in 1810. It was submitted to the Berlin Academy Exhibition of 1810 where it received remarkable praise and appreciation. It was so highly valued that King Frederick William III of Prussia purchased it and added it to the royal collection.

Abbey in the Oakwood is a perfect example of the Romantic movement that dominated the art world from the late 18th to mid-19th centuries. Romanticism valued imagination over reason, feelings over thinking, and subjective opinions over objective perspectives. Therefore, Romanticism was essentially an artistic rejection of the Age of Enlightenment. Order, logic, and reason had fallen; giving rise to chaos, irrationality, and feelings.

Landscape painting became an independent and respected genre during the 19th century. Romanticism allowed landscapes to take on more symbolic and allegorical overtones that were not previously used. The idea of the Picturesque came into fruition alongside discussing spiritual, moral, historical, and philosophical issues.

The time of day, the weather, and the seasons added symbolic meanings to Romantic landscape paintings. The vibrant or decaying state of trees, plants, and buildings also added visual complexity, such as the bare oak trees and ruined abbey found in Friedrich’s Abbey in the Oakwood.

Abbey in the Oakwood encapsulates the sublime. It is not a happy painting. Death saturates the image through the stark landscape, leaning tombstones, somber clothing, leafless trees, and ruined structures. Everything seems to be declining or lifeless. However, not all is lost. While the allusions to death and destruction are obvious and cannot be dismissed, there are also transcendental allusions to consider.

Friedrich’s Abbey in the Oakwood shows a ruined abbey against a wintry sunset with a pale moon rising above. A sense of time is explored on the human, natural, and eternal scales. The ruined abbey suggests the human scale. Architecture is a human achievement, and like this Gothic abbey, time can be cruel to humanity’s achievements.

The abbey’s large window suggests that bright stained glass once adorned its façade. A roof once clad its interior, and walls once surrounded its parishioners. But now, all is in ruins. The abbey also marks the different stages of human civilization. The painting’s abbey was inspired by Eldena Abbey near Greifswald, Germany. Like its inspiration, it is a Gothic structure and a symbol of the Medieval era. The Medieval era was once a vibrant and living era of human history; however, Abbey in the Oakwood now shows this mighty era as passed and decayed.

The dusky sunset and wintery landscape evoke the daily and seasonal regularity of nature. Every day features a sunset; and likewise, every year features a winter. Like clockwork, the sun sets and the seasons transition. Sunsets and winters suggest the natural scale, which is much bigger and longer than the human scale. These markers of time occurred before humanity continued through generations of humanity, and continue past the existence of single human lives. The individual may die, but nature continues. This natural scale is larger than our scope of experience, which is wholly suggested in Friedrich’s Abbey in the Oakwood.

High above the human and natural scale is the moon. And this waxing crescent moon in Friedrich’s Abbey in the Oakwood suggests the eternal scale. It is time on the universal scale when the phases of the moon began millions of years before seasons and humans existed. The cosmic scale is so vast compared to that of the human, it is essentially eternal. The moon marks the third and final timescale found in this piece. Through this painting, we delve deep through the layers of time: from the human, through the natural, to the eternal.

Caspar David Friedrich painted Abbey in the Oakwood as a medium to explore the human condition. The landscape takes on otherworldly meanings and showcases how we are just one moment in the natural and eternal timescales. Renewal and rebirth are alluded to, and even stages of religion could be implied: from the Polytheism of tree worship, through the monotheism of Christian beliefs, to the Atheism of modern apathy. Friedrich’s Abbey in the Oakwood is a macabre masterpiece that captures the un-pretty themes of Romanticism. Pretty paintings can be all alike; however, every unpretty painting is unpretty in its own way.

Bewiebe, Birgit. “Abbey in the Oakwood.” Alte Nationalgalerie. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Gardner, Helen, and Fred S. Kleiner. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 14th ed. 762 & 770. Boston, MA: Wadsworth, 2013.

Harris, Beth and Steven Zucker. “Friedrich, Abbey Among Oak Trees.” Khan Academy. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Klosterruine Eldena. Photograph. Eldena Monastery Ruins. University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald. Accessed June 5, 2020.

“Phases of the Moon.” Solar System Exploration. NASA. Accessed June 5, 2020.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!