5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

George William Russell, known as AE, painted the spirits and visions he had seen since childhood. His Irish landscapes are topographically familiar, but juxtaposed with fairyland qualities. Russell’s paintings glow with light and soft colors, which often form a background for faeries and spirits of folklore.

George William Æ Russell (1867-1935) was a follower of Theosophy, an occult philosophy largely influenced by Eastern spiritual beliefs and practices. Of great importance to AE Russell’s artwork is the Theosophical idea of unity between all creatures – that all descend from the same origins. Connecting the dots between his visions and Theosophy, Russell believed he saw the Sídhe, pre-Christian Irish gods or faerie people. To Russell, the Sídhe represented the true and original race of Irish people.

Living through a period of great political turbulence in Ireland, Russell’s paintings might betray anxious feelings over the meaning of Irish identity. The 19th and 20th centuries saw a revival of interest in Celtic mythology and Irish folklore, known as The Celtic Twilight. Artists, writers and poets like Russell and the Yeats Brothers were inspired by these old stories, retelling them in fresh words and bright colors.

The Stolen Child is a pastel and pencil drawing. Three of Russell’s Sídhe stand in a landscape, softly colored in blue and lilac. The three tall creatures share features and identical dress. Their bodies overlap as if to emphasize their unity of spirit. Tenderly, the foremost Sídh reaches out to take the hands of a little girl. She looks vulnerably small and shy before the stately Sídhe. Her little body is sweetly rounded in shape, from her bobbed hair and round cheek, to the outward swing of her dress. In contrast the long robes worn by the Sídhe emphasize their great slender height.

The Sídhes’ robes pool and fade into the ground, as though they have risen up out of the earth. All the figures look weightless and translucent, drawn onto the misty background that shines through them. The figures and landscape merge tonally, both drawn in shades of blue and white chalk. Likewise, the line between earth and sky is blended so they appear to drift into each others space.

He explores the unique atmosphere and colors of that short time. Undefined forms blur into their surroundings, and the sky still glows, pin-pricked by the shining stars.

The Sídhe form a powerful light source, equal to the bright glow of the stars above. Around their heads radiate thick short strokes of white chalk, representing crowns or halos. Russell’s Sídhe both entice and unsettle. They look a cross between faerie and angel, attractive but scary in their “otherness.”

The smoking chimney and glowing window of a cottage can just be seen. This could be the little girl’s home, possibly she has not yet been noticed missing. Faeries stealing children, or swapping them with their own, is a recurring theme in folklore. Russell’s depiction is considerate and gentle regarding the Sídhe – they look like guardians rather than mischievous thieves.

William Butler Yeats wrote a poem, also called The Stolen Child, in which the faeries offer the child a way out from a sorrow filled world:

Come away, O human child! To the waters and the wild With a faerie, hand and hand, For the worlds more full of weeping than you can understand.

W.B. Yeats

Both Russell and Yeats seem to sympathize with the faeries’ point of view. The wild landscape and carefree life of the faeries may have represented an escape from the cares of modern life.

Although Russell attended art schools in Dublin, his family could not support his artistic vocation. Therefore Russell worked aside from painting and writing poetry, becoming a successful writer and newspaper editor. His wide scope as a writer included the mystical, Irish politics, and rural farming. Despite the dreamy subject matter of his paintings, Russell shows interest in the people and issues around him.

They frequently feature dunes and rocky beaches, fields with hillsides, and old stone walls. Sketching on visits to Donegal, Russell used these observations as the base for paintings throughout the year. These paintings from Russell’s later career often feature anonymous human figures. Women and children play and wander, stop and gaze, within a vast landscape. Russell also emphasizes a human connection to the natural world, his figures sharing the soft forms and gentle coloring of their surroundings.

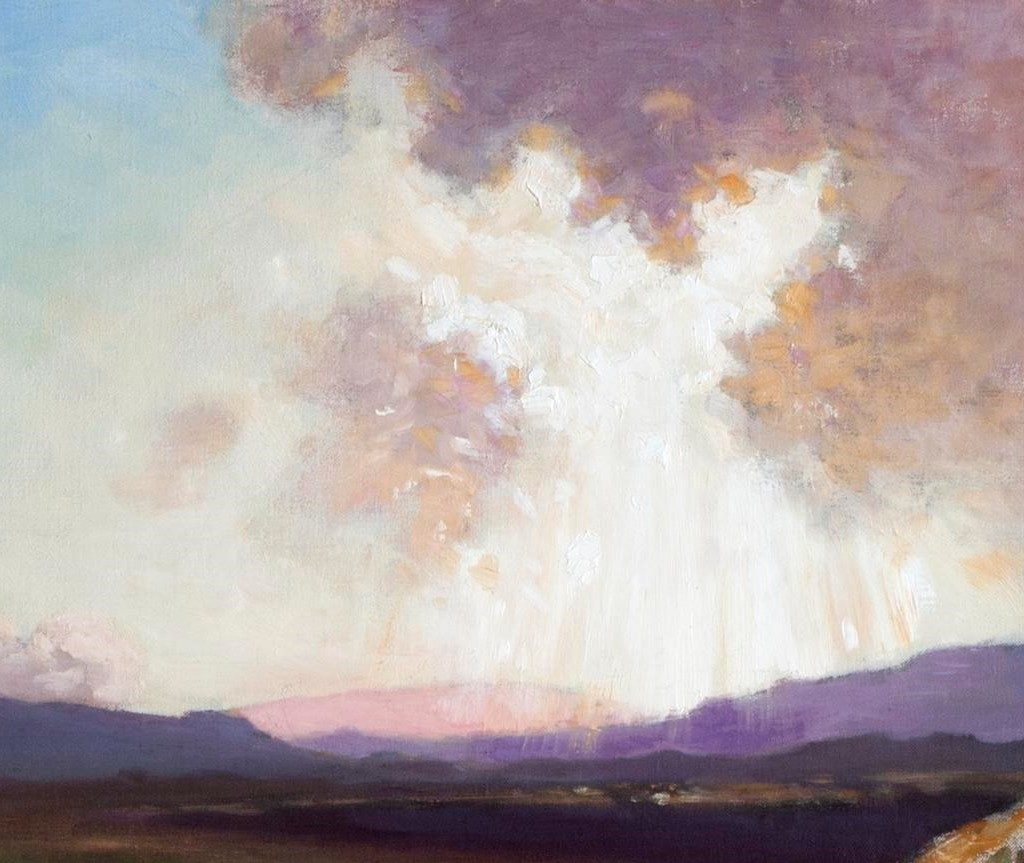

In The Watcher, Russell paints a vast and rugged landscape, bordered in the distant by dark lilac hills. In the foreground, a lone figure dressed in blue sits by the side of a shining river, opposite a rounded bank of grass. The anonymous figure might raise questions of identity and purpose. Are they waiting for something to happen? Or simply lost in thought?

Still and quiet, the figure, the river and opposite bank sit in harmony. Not a breath of wind disturbs the surface of water. In contrast, the sky above is dynamic with change. It varies in color, from the clear blue patch in the top left, cloud forms of pink and lilac dappled with orange. Sunlight bursts out from a large cloud mass in white beams, streaming to the earth.

The sky forms the largest half of the landscape; the colors feel joyous, the bright light looks like a symbol of hope.

The field is painted rather dark in mossy green, brown and orange. However, it seems to shimmer, as the colors vary in tone and are painted with the same merging and dappling strokes as the sky. The river attracts the eye as it cuts a silver trail through the dark earth. The light reflected on its surface looks almost magical, it shines so brightly out of the ground.

Russell entwines the painting with mysticism. Time feels suspended in the lonely landscape, sparkling with color and light. It is easy to imagine that the blue boy might just represent Russell himself, gazing into the river as the stories of faeries and folklore play out around him.

Hewitt, John. Art in Ulster 1, 1977, Blackstaff Press LTD.

Deirdre, Kelly. Spirit Level, Irish Arts Review, Spring 2017, Vol 34, No. 1.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!