5 Ultracontemporary Artists Redefining the Korean Art Landscape

The dynamic South Korean art scene is quickly becoming one of the most prominent globally, blending rich traditions with cutting-edge innovation. And...

Carlotta Mazzoli 13 January 2025

25 February 2021 min Read

In 2019 the auction house Sotheby’s sold Kerry James Marshall’s painting Vignette 19 for $16 million. That’s a lot of money for a work by a living artist. But last year the same artist did even better. In May 2018, hip-hop producer and rapper P. Diddy bought Marshall’s monumental painting Past Times for the sum of $21.1 million. This is thought to be the highest price ever paid for an artwork by a living Afro-American artist. How a socially disadvantaged artist made his way to the top: a story of two brothers in arms, Charles White and Kerry James Marshall.

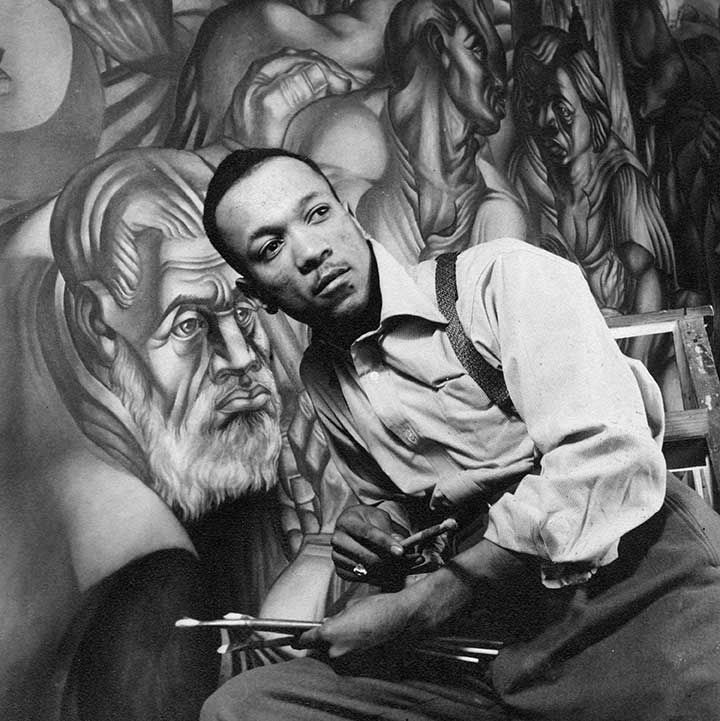

Kerry James Marshall (born 1955) didn’t make his fortune out of the blue. As an art student, he showed great admiration for his teacher Charles White (1918-1979). What attracted Marshall to White’s art was his technical virtuosity in depicting blackness.

Charles White was a successful and well-known artist during his lifetime, which at that time was unusual for a black artist. Even museums collected his work, so that gives you an idea of the scale of his fame. After his death, this changed, and he was almost forgotten. White’s popularity faded after his death because he was a person of color in an industry that unfairly favored white artists. Moreover, the art scene preferred abstract and conceptual styles instead of White’s social realism. However, because his work stayed relevant over time, he has recently been reintroduced. Surprisingly, the reason he was forgotten was also the reason why he was successful during his lifetime: expressing himself as a black man.

Politically active in the years 1930/1940, he considered his art as something that could contribute to a changing world. He was very engaged and stood up for the rights of his fellow Afro-Americans. It’s worth mentioning that he had a close friendship with another fighter for Afro-American rights, the famous singer Harry Belafonte.

His engagement was not only political. Even as a young student, he was eager to share what he had learned. At a later age, as an art teacher at the Otis College of Art and Design, he approached his courses with a strong flavor of Afro-American history and tried to teach his students about humanity and what black power stands for.

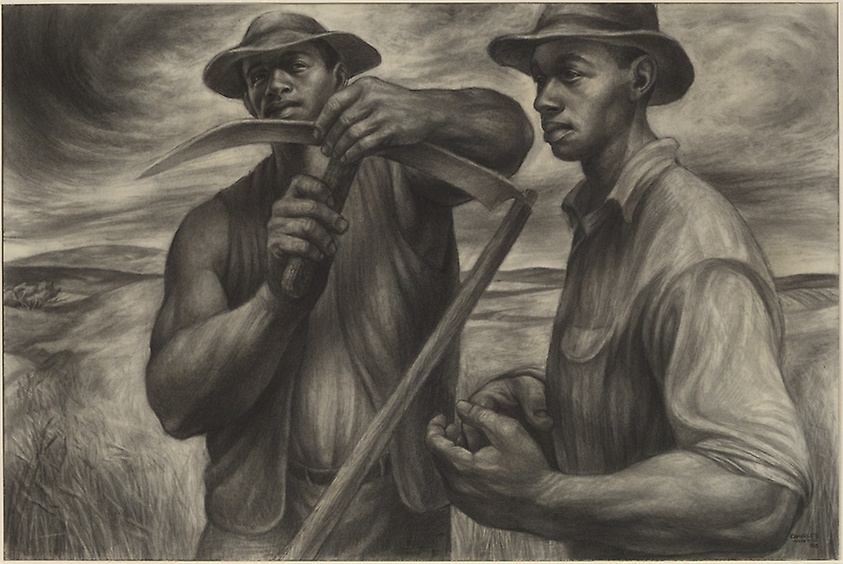

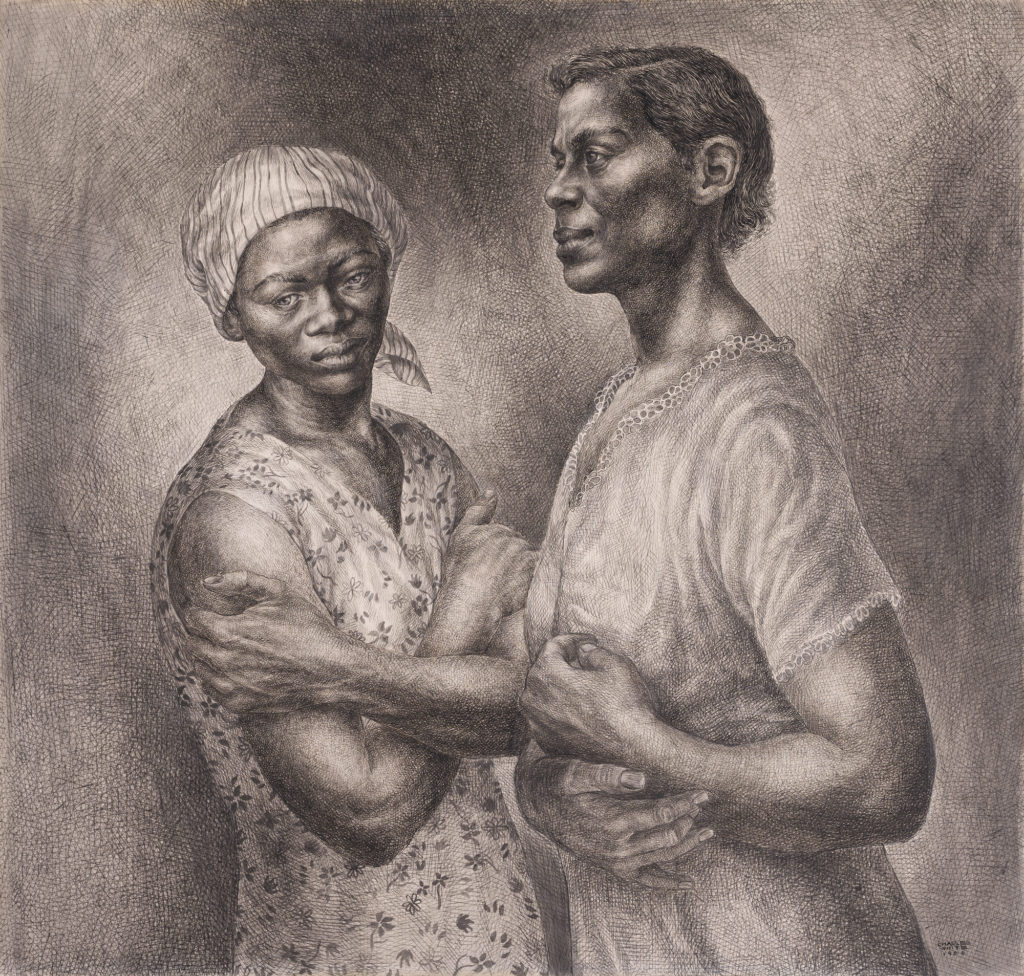

During his four-decade career, White committed himself to creating powerful images of Afro-Americans. He managed to express a kind of proudness in the characters he depicted. His portraits are incredibly detailed: the eyes, the hair and even the hands are very realistic. A typical element of White’s style are strong arms and over-sized hands. In fact, they refer to the artist really believing that the portrayed were accomplishing things: they had power within and if they wanted, they could overcome all obstacles. In other words, every man or woman he portrayed was fighting for their rights.

The drawing Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep illustrates this in a beautiful way. When you look at the faces of these women there is serenity and hope. While one is sunk deep in thought, the other gazes into the future. Both women show strength, not only in vision, but also in their muscles (look at their arms).

Kerry James Marshall was one of White’s students at the Otis Art Institute. He quickly took on White’s ideas about black power and wanted to contribute to the awareness of Afro-American artists. In below video he explains that when you look back through art history, you mostly will see European works in museums. Though these works are all fantastic, he has difficulties in finding a place as a black person. It’s like something has gone exclusively to European artists in the value system of art. As Charles White did before him, he also wants to put this straight and started by painting black figures.

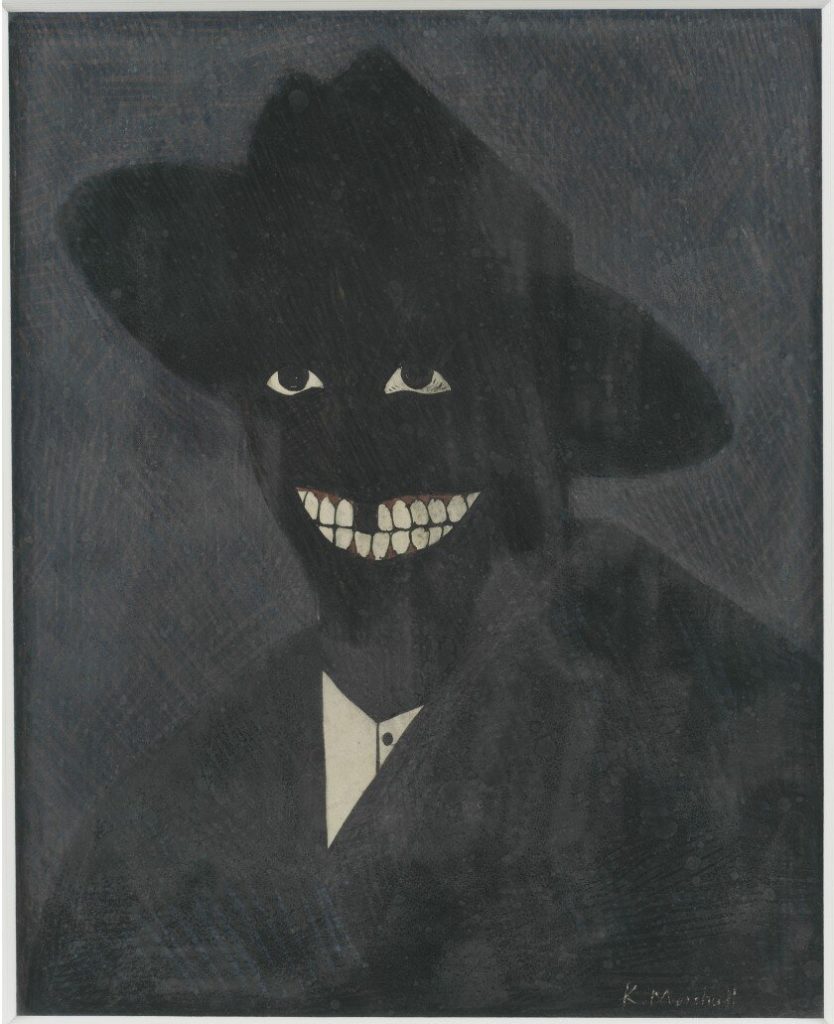

He began painting with A Portrait of the Artist as His Former Self. This is a black-on-black painting who is likely to disappear in front of the viewer’s eyes. Marshall referred to the absence of black artists in art history by evoking Ralph Ellison’s book Invisible Man.

“I am an invisible man. A man of substance, of flesh and bone, fibre and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.”

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man, 1952.

You will notice that he actually doesn’t depict real people in his paintings. Instead, he is using black figures, as if they were silhouettes. It is similar to what Jean-Michel Basquiat did in his graffiti paintings. By abstracting people, he refuses to express both negative and positive stereotypes of black people. By these means, the viewer is forced to discover forms instead of real people. He is also likely to distance personal feelings in favor of the acceptance of black subjects.

In 1963, Marshall moved with his parents to the Nickerson Gardens public housing project in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. This place would take an important place in his artwork.

He would be influenced by two events that were related to his neighborhood. Firstly, the establishment of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. This ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination based on race or color. Secondly, the next year, the Watts riots escalated when the local police force was involved in a serious fight with Afro-Americans. It turned into a massive riot and after it ended, six days later, almost 1,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed! Marshall wasn’t even 10 years old at that time. So it is easy to understand that these events had a permanent impact on him and inspired him to paint the Garden Project series.

Many Mansions is the first in the Garden Project series and is filled with irony. Despite the title of the work there are no mansions on the canvas, only flats destined to low-income families. Black figures, dressed in their Sunday’s best, are working in the public gardens and the painting looks strangely cheerful. The red ribbon above states a variation of Christ’s quote

“In my Father’s house there are many mansions.”

New Testament, John 14:2.

It is clear that Marshall isn’t interested in making a simple, black painting. He fills it with layers of meaning, resulting in a complex image reflecting on life.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!