Art on Screen: 12 Movies about Artists Worth Seeing

Whether troubled or exciting, extraordinary or perfectly average, the lives of artists are an endless source of inspiration for cinematographers.

Edoardo Cesarino 17 February 2025

Agnès Varda was an important figure in the New Wave (French: Nouvelle Vague) film movement. She is known for making her own cinema. Her sensitivity and criticism manifest in several ways, among them the contact between cinema and other arts.

The French director has had an extensive career and has produced autobiographical, fictional, and documentary films. The approach of her work takes position at the same time that she captures sensitivity.

Many of these pieces operate within a film genre that expresses itself in a hybrid way. As a result it highlights the ways in which the director deals with image representation.

This is because, by making them, Varda demonstrates an assiduous taste for the arts in the composition of her own frames, but also as a starting point and articulation in her filmography. Overall, the art is an element that connects the universe of the other to that of the director herself.

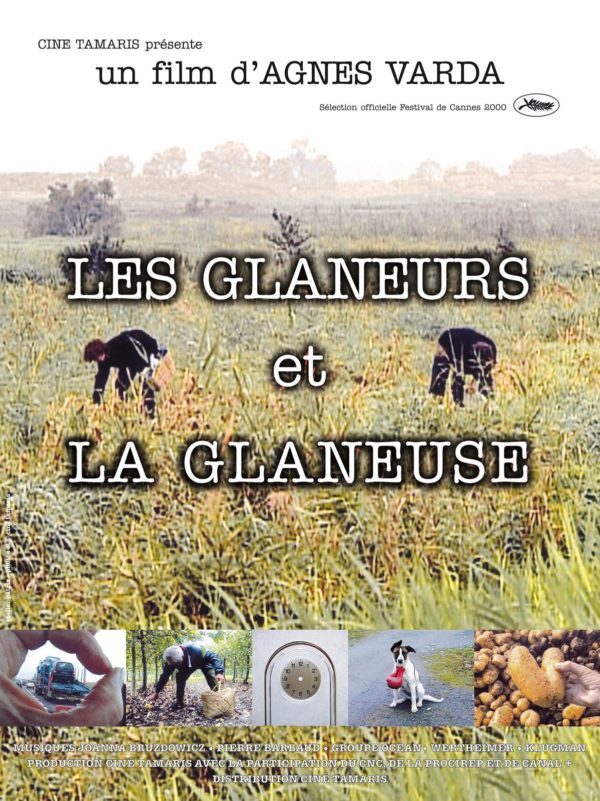

For instance, in The Gleaners and I (2000), Millet’s painting The Gleaners is the spark of the director’s own restlessness and stimulates her to get in touch with other people. However, it puts in mise-en-scène the painting and resigns it through gestures, as Cristian Borges and Samuel de Jésus define in Memory of Gestures In The Films Of Agnès Varda.

Above all, what her cinema promotes is the encounter of her subjectivity with the people and things she films. Her camera thinks and has life; she manifests her gaze on the world because she creates and transfers her impression onto it.

In fact, she generates an exchange between the elements of the film. The director, the active world in front of her lens, and the spectator create convergences because she knows how to assume the role of observer and idealizer of images at the same time. As a result, she enchants us by exploring life through the cinema, promoting the art of encounter.

It is not by accident that her work is permeated with honesty and virtue when she creates images. Before making films, Varda studied at the Louvre School, was a photographer – a craft she never abandoned. Later, in 2003 she also became a visual artist.

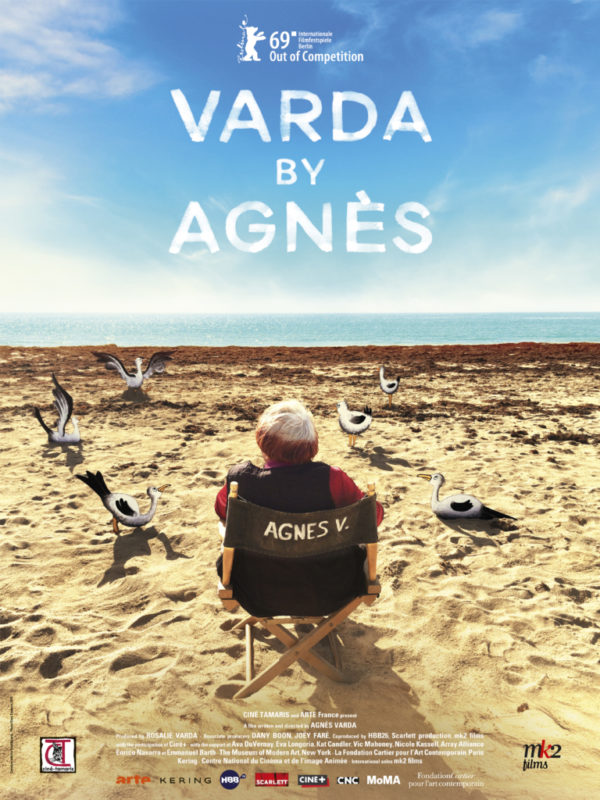

The filmmaker debuted her career in 1955 with the film La Pointe Courte. Then, she made films during the Nouvelle Vague, as Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), and continued to make films until the end of her life with Varda by Agnès (2019). The artist died on March 29, 2019, at her home in Paris, next to her family and cats.

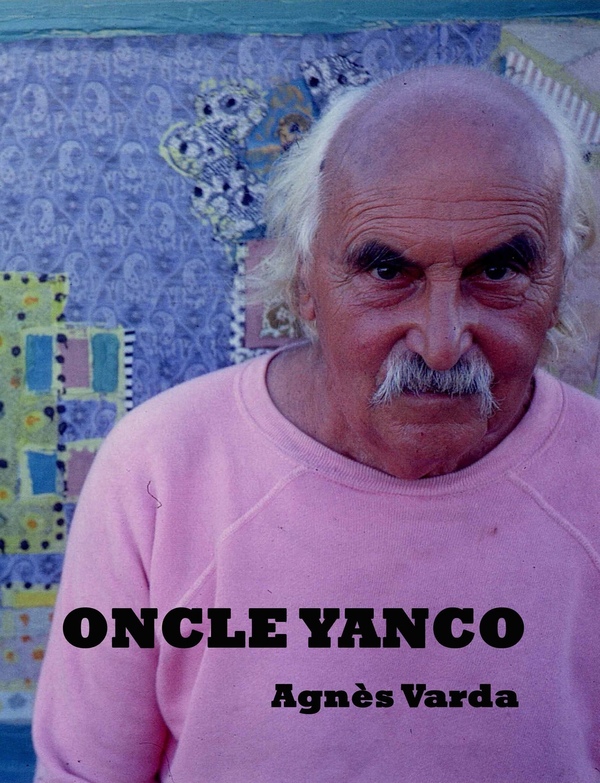

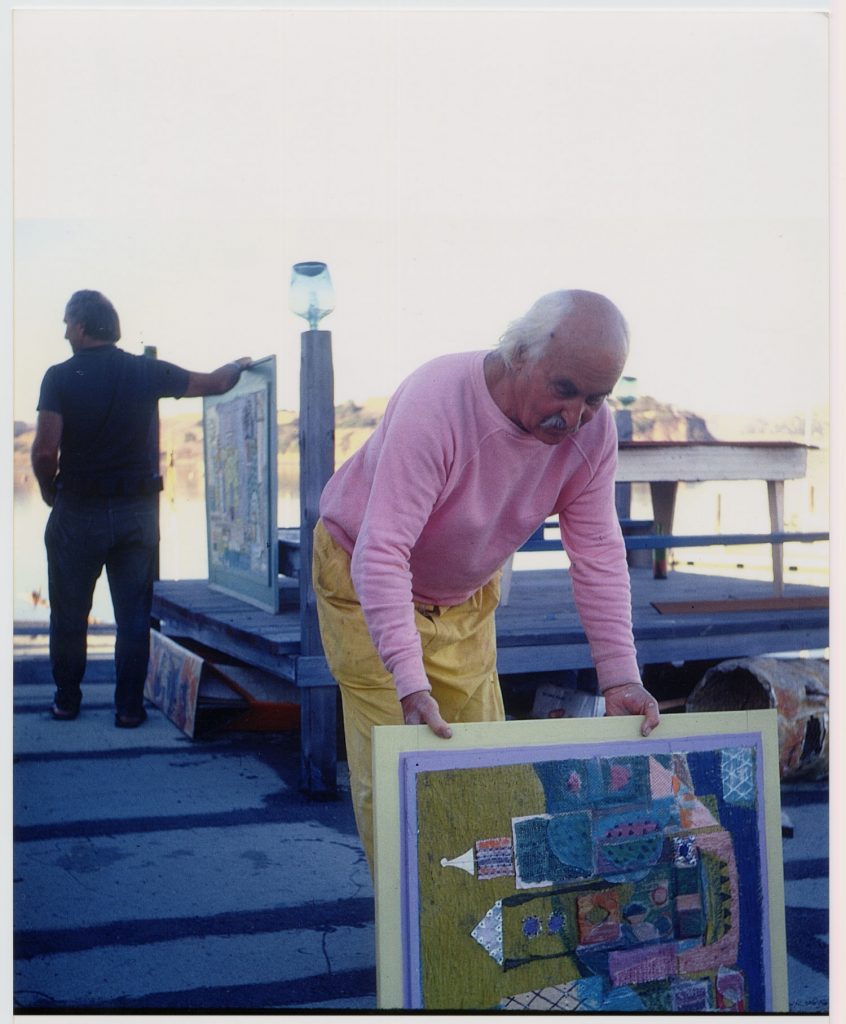

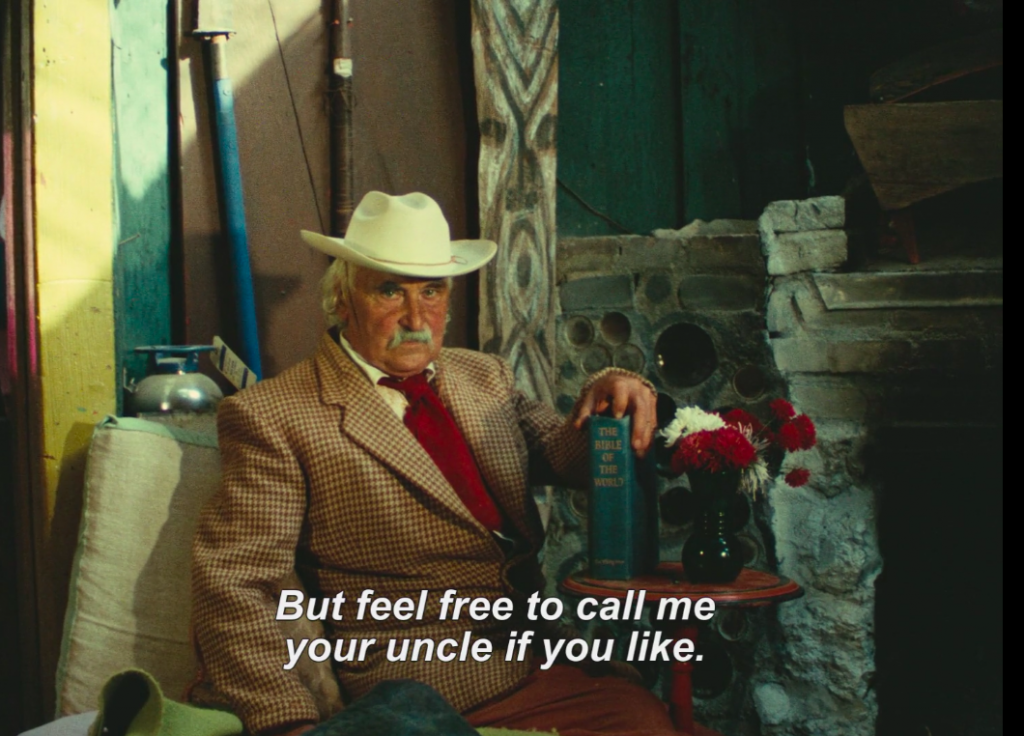

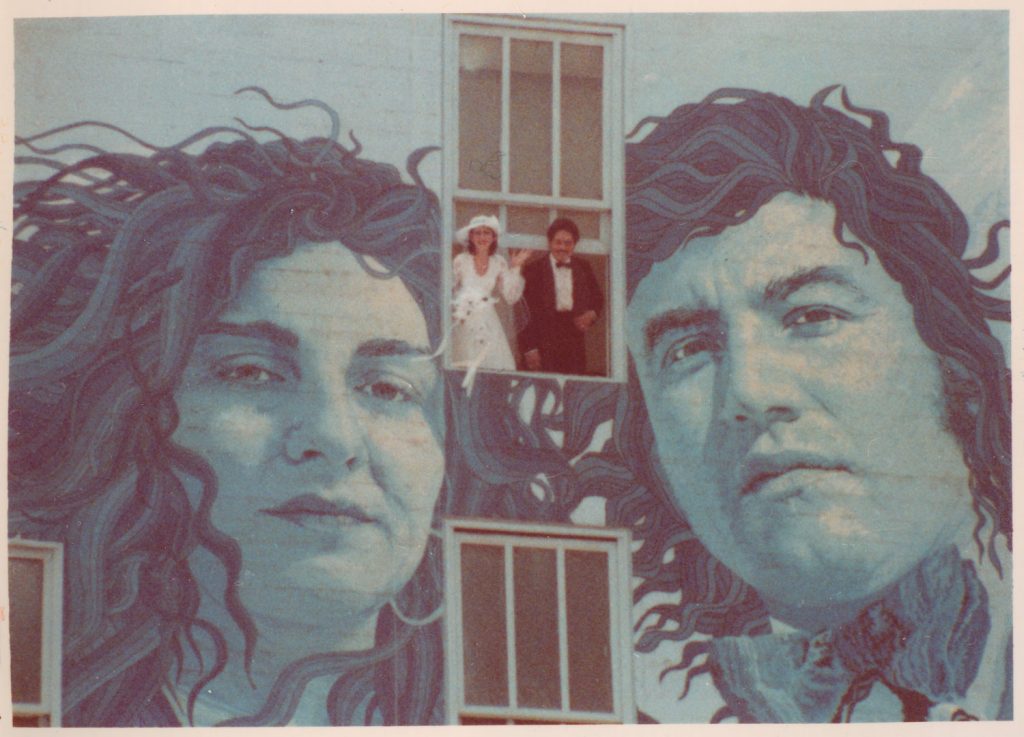

In 1967, while in San Francisco to publicize her last film, the director is motivated to meet an uncle back then, unknown, the painter Jean Varda who leads a hippie life on the banks of a water suburb in San Francisco.

The work revolves around this encounter, with a person from her family who she has never met. Soon, her search for points of convergence and affection gives space for encounters between their crafts, painting, and cinema. We also see the discovery of a bohemian and anti-conformist man, who the director builds a look of admiration and affection.

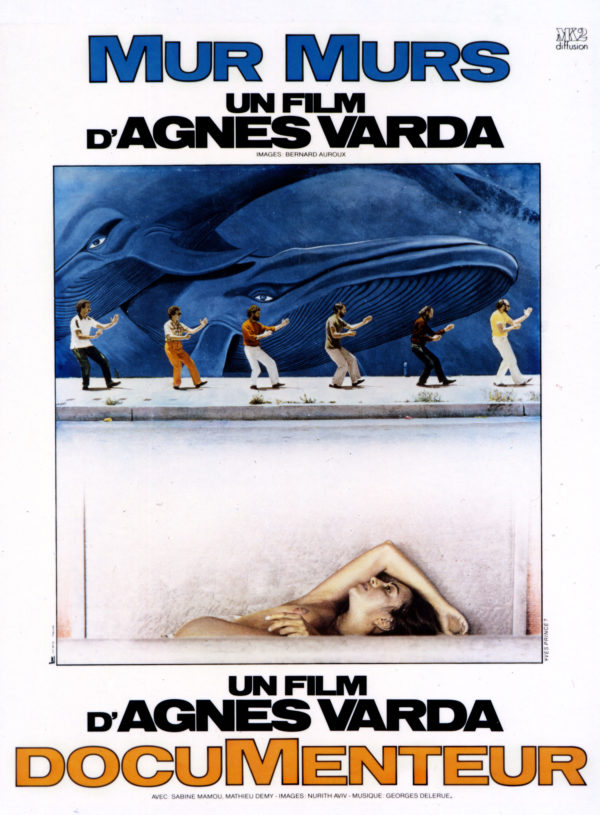

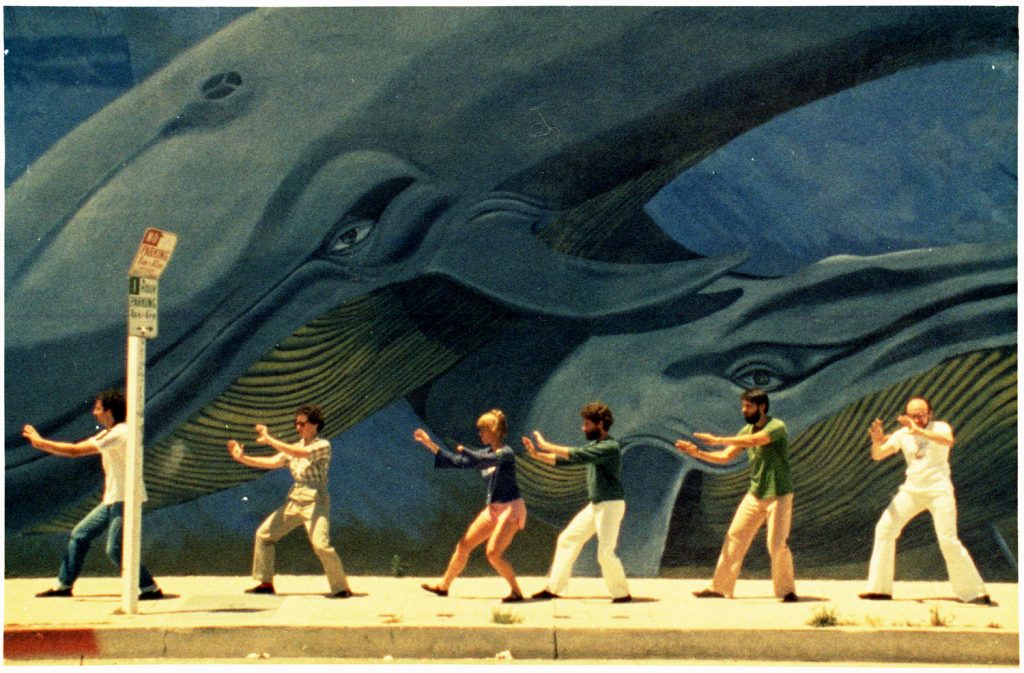

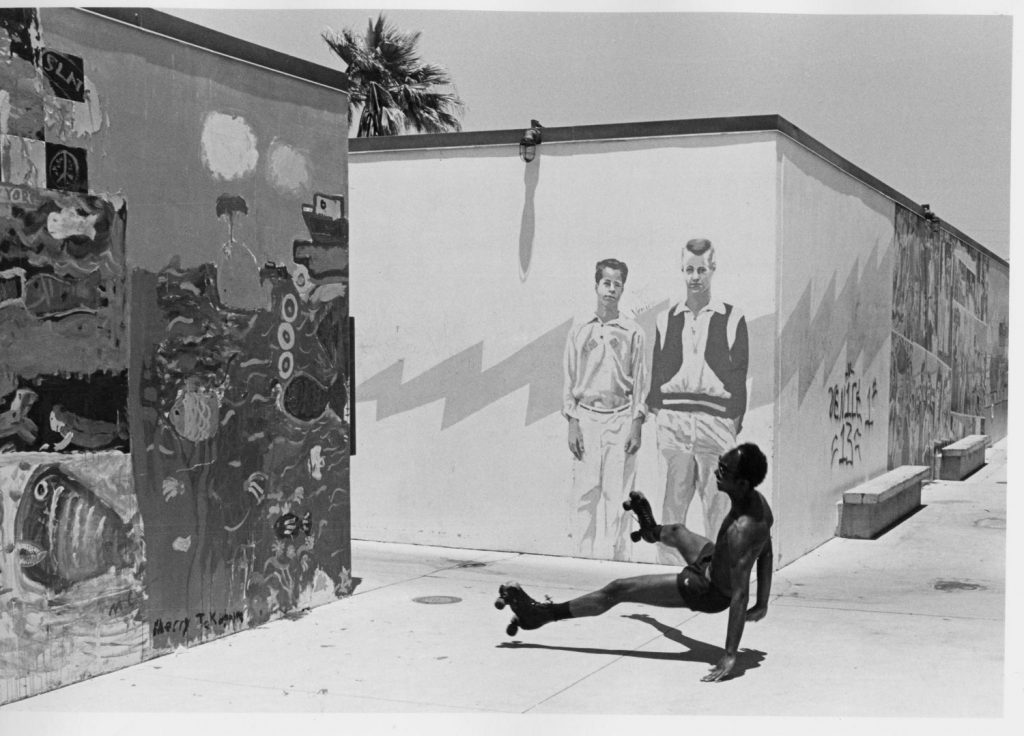

When Varda later returns to the United States, she has a curious look at the walls of the neighborhood where she lives in Los Angeles. Hence, the artist explores these walls that propose the accessibility of art that transcend the galleries but also dialogue the importance of these outlets for black and Latin American artists in the communities that are found. At the same time, the director’s look at small events and spontaneous moments that happen in this search gives subtlety and vivacity to the film.

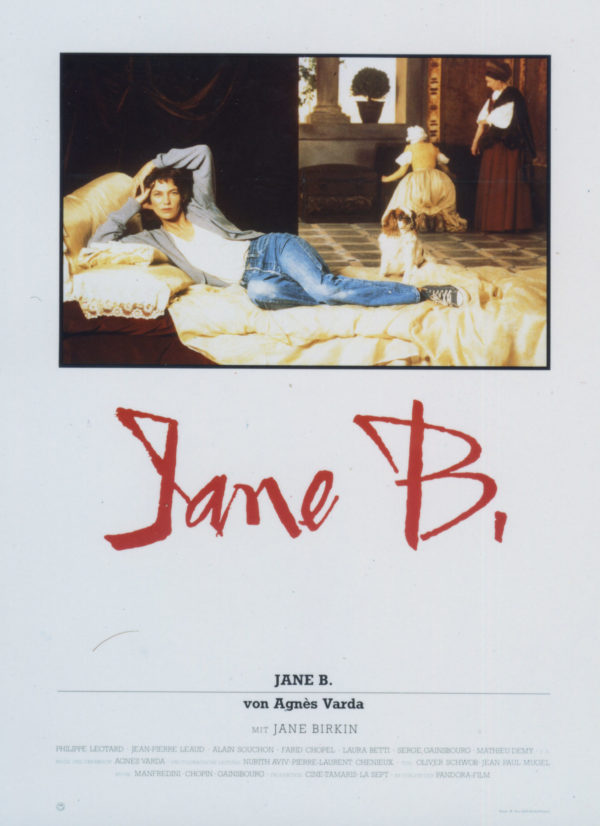

During the conception process of the film The Kung Fu Master, the French-English actress Jane Birkin shares her concern about reaching the age of 40 with Agnès Varda, who believes it is a beautiful age to make a portrait about the actress’s life.

The film interviews the actress who assumes the role of several “Janes” – D’Arc, Jane of Tarzan, Calamity Jane, and herself. Simultaneously, in doing this “play” of character exchange she creates with the director a small fiction homage to icons. In fact, this ends up revealing much more about the actress in her free dialogue with the director.

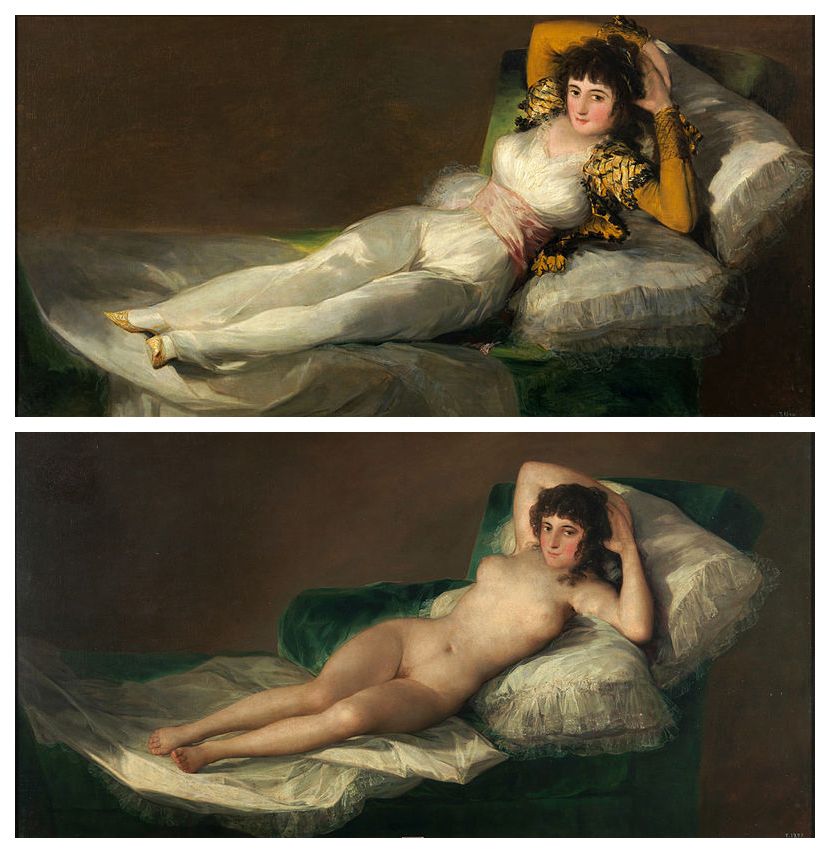

Varda masterfully carries out this cinematographic portrait and ties in references to paintings by great painters such as Francisco Goya and Titian in the composition of her moving images.

This film focuses on how contemporary forms of consumption generate waste. In this case, Varda investigates what happened to the gleaners of the past and how they are configured today in the cities and countrysides in France. Gleaners who live off the recovery of leftovers, whether by necessity or not, gain a voice.

The director, who is also a character in her own film, positions herself as a recoverer of images and uses, for the first time, a digital camera. She draws inspiration mainly from Millet’s painting, The Gleaners, but also from paintings by other artists such as Breton and Hédouin and does not limit herself to using only works by “museum artists”.

Above all, Varda in, The Gleaners and I, manages with an unequaled lightness to talk about herself, her admiration for painting, her craft, and her old age, of others and of the world.

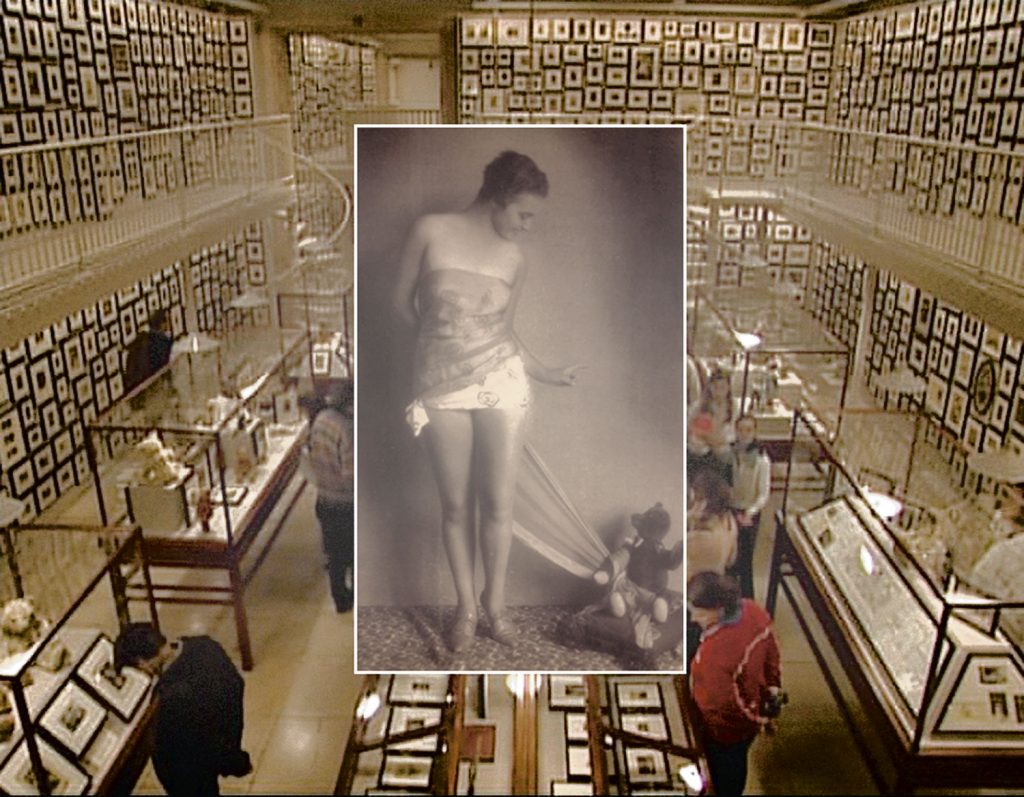

Here the director focuses on photographs – still images that are supposed to be able to “freeze” time. The film was realized in 2004, due to a visit to the exhibition of the artist Ydessa, The Living, The Bears, and Etc. Thus, Varda decides to meet the person who gathered a large collection of photos of people in different (and unusual!) situations with a teddy bear.

The artist, whenever she could, acquired the bears that were in the photos that participated in her curatorship. It should be noted that is not essentially a film about Ydessa, but about what the subjects have in common: the image and what it incites in the viewer.

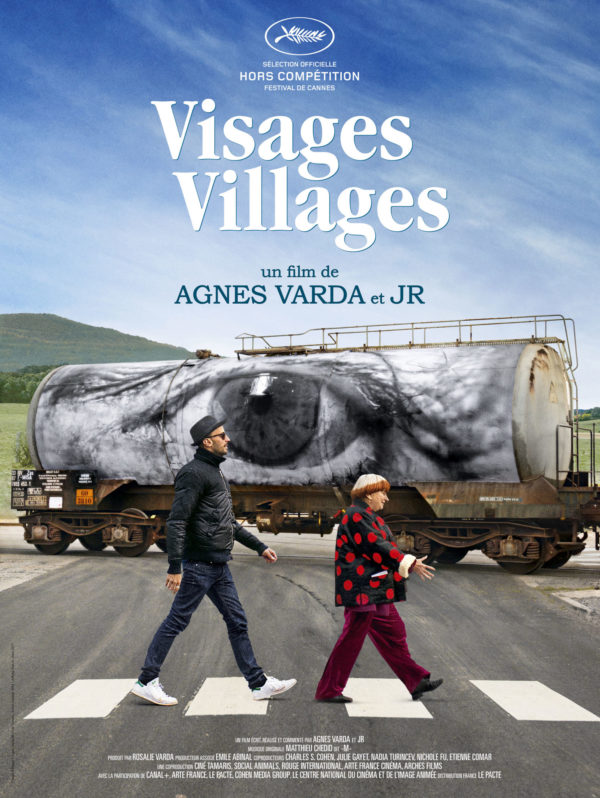

As a consequence of Varda’s meeting with the French artist JR (who turns his photos into huge urban collages), in 2015. Soon, a great desire emerges to make a film together, away from urban life and with JR’s photographic truck.

Faces Places unfolds from points in common about the two of them: questions and passion about images, more precisely, about the places and the device they use to share and exhibit their works. Likewise, artists unabashedly approach the people who cross their path, listen to them, photograph them, film them, and exhibit them constituting a web to the narrative that interweaves the history of friendship between the two.

Agnès as a good storyteller makes her last film under the stage lights, looking at her journey through her 3 lives as a photographer, filmmaker, and artist. In contrast to Beaches, Varda does not reconstitute the images that were present in an affective memory but creates a conversation with herself by revisiting images from past interviews that made her and making images that look back on her career.

She opens herself up as an artist and gives a lesson about her creative process, her inventions, what inspires her, conversations and encounters, but mostly, the search of sharing about her sensitivity with the other. In her unique way, she looks at herself and her journey, and of course, without forgetting us, the spectator. She eternalizes herself once again and says goodbye to us, leaving us with nostalgia.

Borges, Cristian, & Jésus, Samuel de. Memória de gestos na obra de Agnès Varda: pintura, fotografia, cinema (Memory of Gestures In The Films Of Agnès Varda). ARS (São Paulo), 8(16), 65-72, 2010. Accessed November 12, 2020.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!