Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Today, Alice Neel is considered one of the greatest portrait painters of the 20th century. As she usually painted her friends, family, neighbors, and people she encountered on the streets, her work is a visual documentary of her era. She made many sacrifices to live and paint the way she wanted. Although it came with a cost of living in poverty and not gaining the recognition she deserved, Neel did not care about painting what was fashionable. Instead, with each stroke of her brush, she challenged issues of racial and social inequality, gender, motherhood, and identity. And in the end, she made it to the Met!

Alice Neel was born on a cold day in January 1900, to a strict, middle-class couple in Pennsylvania. She made a habit of observing people around her from an early age. When she saw a neighbor exposing himself on his porch, she realized there were no artists around to paint such a controversial event.

Her parents did not approve of her desire to train as an artist. Neel’s mother said to her: “I don’t know what you expect to do in the world, you’re only a girl.” However, this encouraged headstrong Neel further and she went on to study at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women in 1921. Little did her parents know, she was going to grow into a pioneering artist who would paint a series of ground-breaking nude portraits.

Upon graduating in 1925, Neel and her first love – a Cuban painter named Carlos Enríquez, married. Shortly afterward, the newlyweds relocated to Havana. Two years later, Alice and Carlos moved to New York with their young daughter Santillana. What followed was a tragedy that broke the couple’s marriage. Just a month before her first birthday, Santillana died of diphtheria. Soon after, the couple had another girl called Isabetta.

In 1930 Enríquez family offered to send the pair to Paris. As two burgeoning painters desperate to flourish in the art world, they decided to leave their daughter with the family in Cuba. She and Carlos had planned for him to accompany Isabetta to Cuba while Alice stayed with her mother. She thought “Oh, isn’t that great? I’ll paint all these pictures that I want to paint.” However, while Carlos was away, she wrote:

The nights were horrible at first. I dreamed Isabetta died and we buried her right beside Santillana.

Alice Neel, artist’s website.

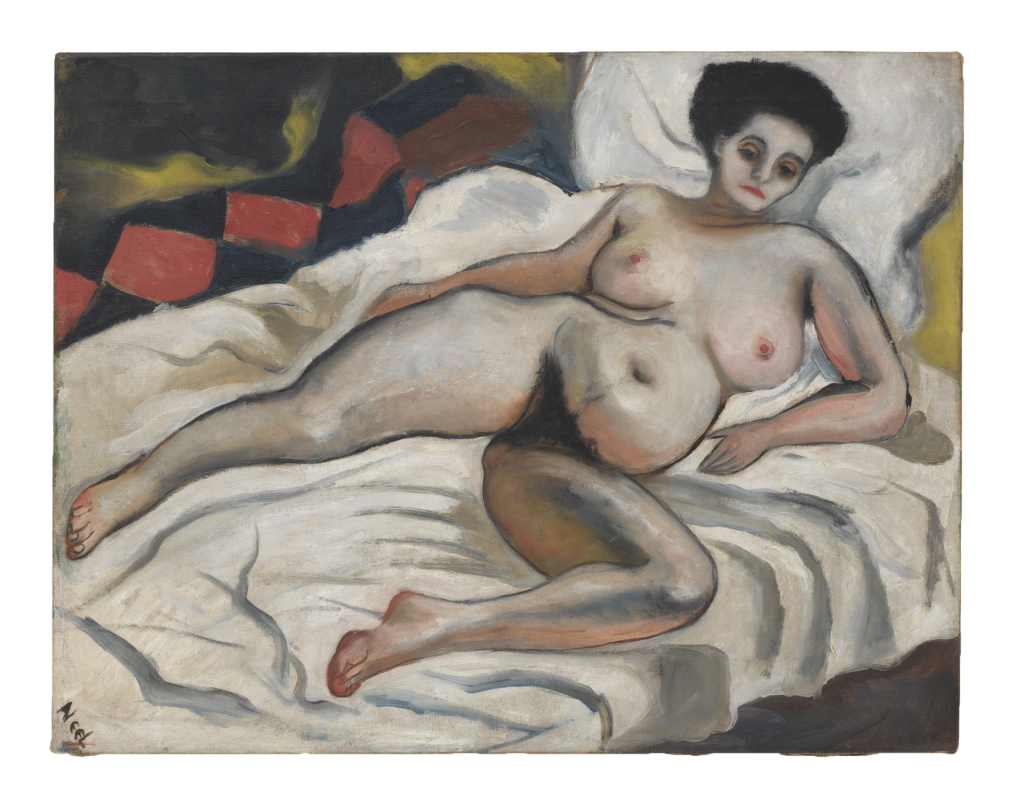

Alice Neel had the most productive summer of her career in 1930 which saw her paint dozens of nude female portraits in just two months.

Following months of painting tirelessly, Neel suffered a massive nervous breakdown. She spent one year at the suicide ward of the Philadelphia General Hospital. During her treatment, she carried on sketching and painting continuously. Paintings from her time in care focused on motherhood, loss, and anxiety. With her release from the sanatorium, she started a new chapter in her life.

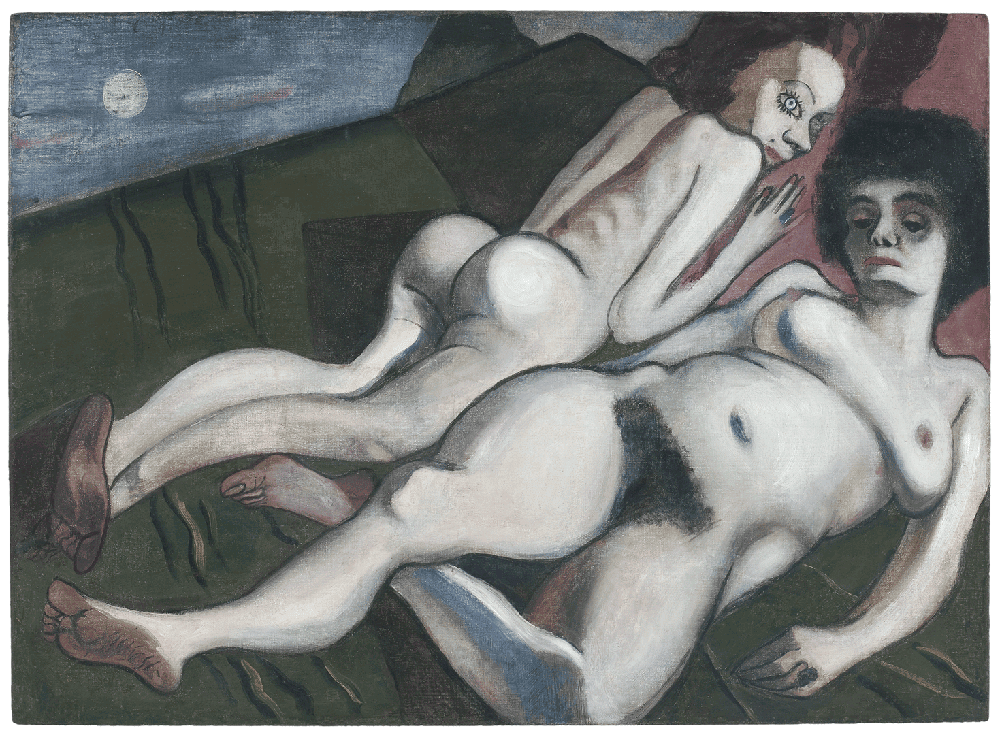

In 1933, she painted several provocative sexual portraits. The most famous one was called Nadya and Nona. Neel believed the clothes that people wore reflected their social class but also hid their personalities. She hoped to reveal more about who her sitters were by stripping off each layer.

Nadya and Nona depicts two nude women lying on a bed. One of the women is on her back, her body relaxed, inviting, and fully exposed: while the other is contained, her arms are drawn up close to her body, her legs are pressed together and locked with her feet crossed. The image is one of contrast – it shows one woman lying easily, despite being nude, and another who is tense and seemingly unwilling to display her naked body. This depiction of two lovers portrays two kinds of female sexuality: Nadya, comfortable satisfying her desires: Nona, inhibited and self-conscious. Neither woman is conventionally beautiful, and their poses are unflattering by conventional standards.

Calling herself a “collector of souls“, Neel provided a snapshot into who her subjects truly were. Abstract Expressionism was the popular movement of the time. However, the artist stuck to her ways and carried on painting with her realistic approach. She had a talent for identifying gestures and mannerisms that revealed the unique identities of her sitters.

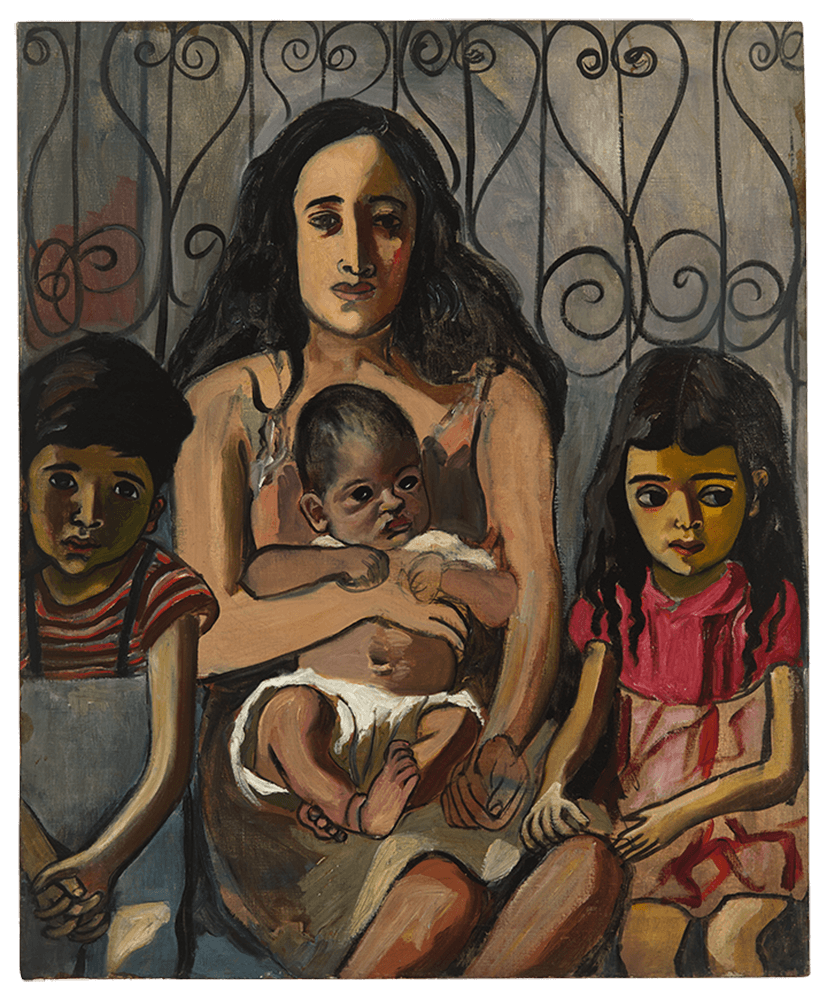

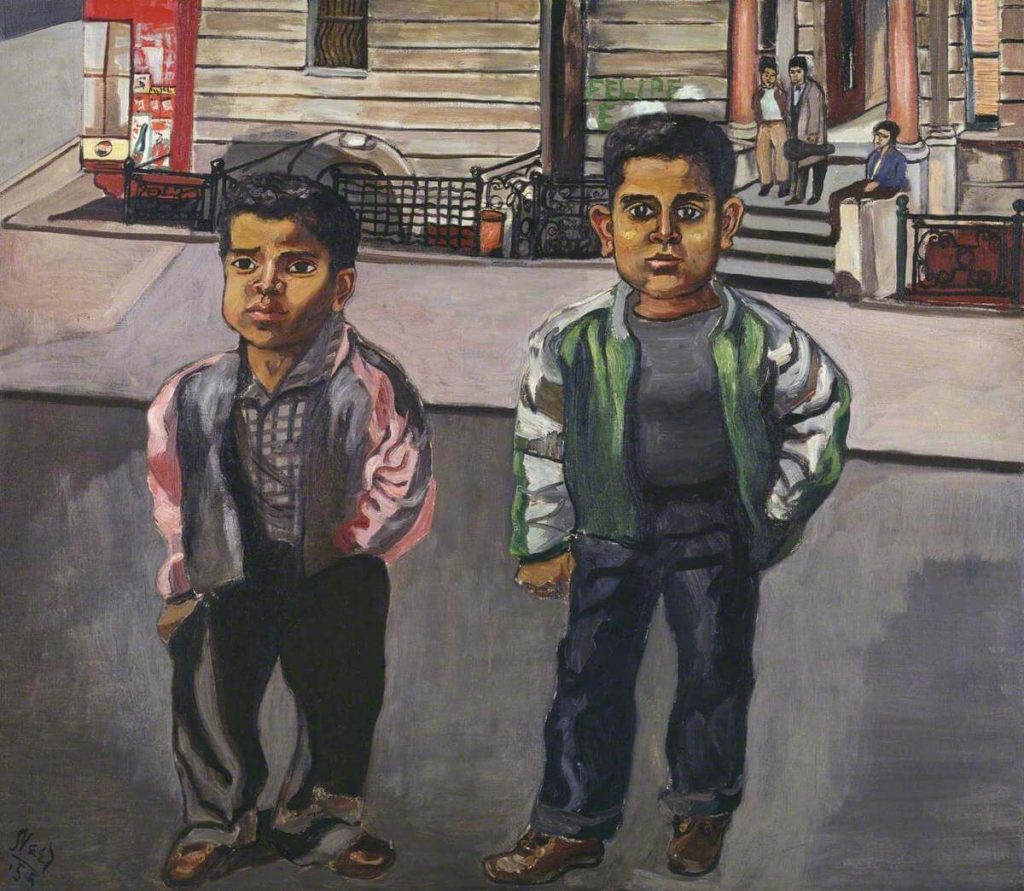

Wanting to paint people of all social classes and create a visual history of her time, she moved to East Harlem. During the 1940s and 1950s, Neel dedicated herself to painting her family, friends, and community. She was not concerned with politics or ideologies; she just wanted to paint the people around her. Her paintings from those decades hold a mirror to uptown Manhattan as a form of documentary.

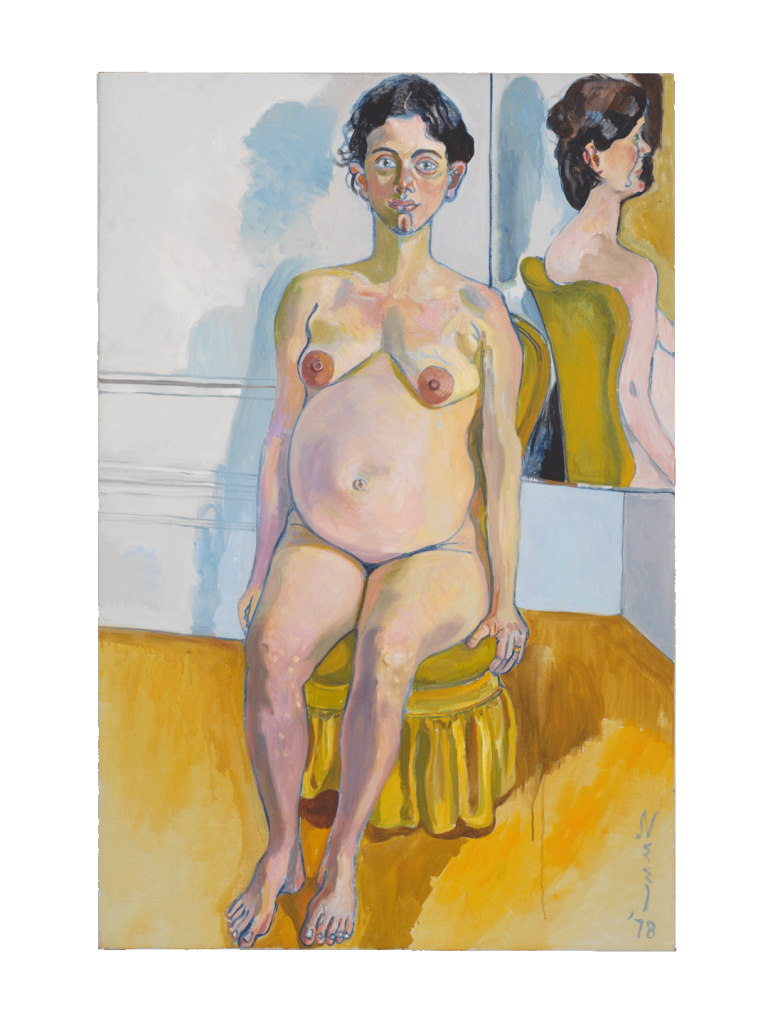

By the early 1960s, Neel’s subject matter changed – she started painting naked pregnant women. They are among her boldest and most stirring portrayals of female experience. When she looked at the history of Western art, she found that it lacked experiences of motherhood. Thus, she took up her paintbrush and began to correct the insulting absence of pregnant women in art history.

When she was asked why she turned her attention to them, Neel replied:

It is not what appeals to me, it’s just a fact of life. It is an important part of life and it was neglected. I feel as a subject it’s perfectly legitimate, and people out of a false modesty, never show it.

Alice Neel, in: Alice Neel, Patricia Hills, 1983.

Neel’s paintings respect the integrity of each woman’s experience of pregnancy; she does not romanticize their condition. Her sitters represent real pregnant women one expects to see in markets, theaters, and on buses. Neel paints the most real and honest human experiences. Her pregnant nude paintings set the best example of her pursuit.

Pregnant Maria shows a reclining figure, her head resting on her left arm, her extended right arm draped leisurely on her hip. She does not pose for display; rather, she has arranged herself for her comfort.

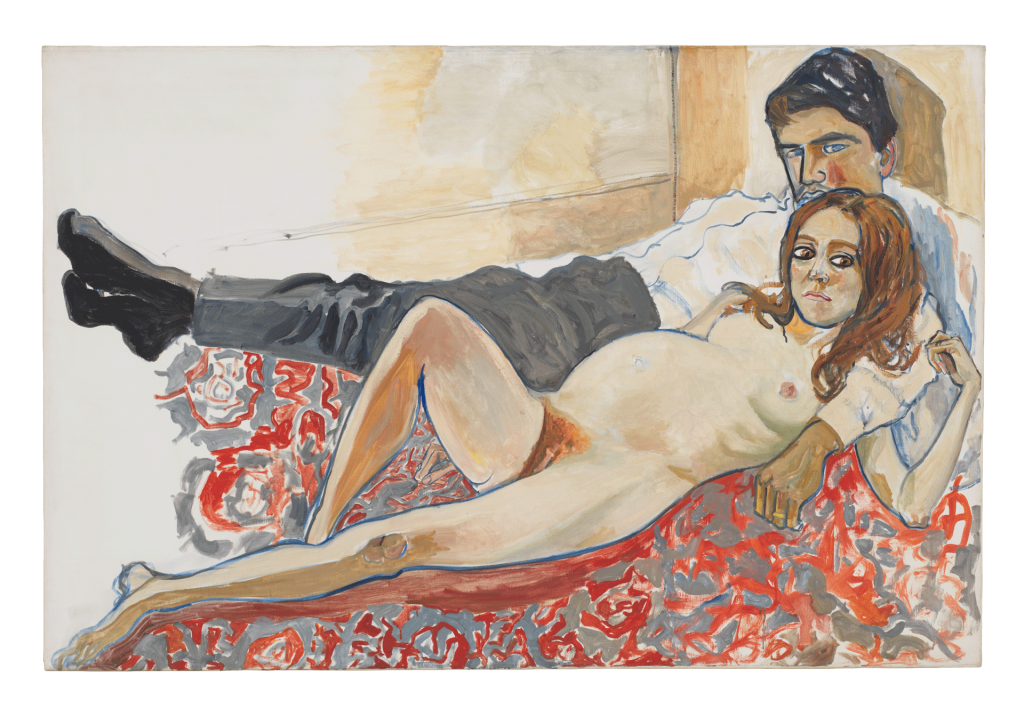

In Pregnant Julie and Algis, a mother-to-be is lying with her partner. Julie looks hesitant whereas Algis fixes his eyes sharply on the viewer. Julie’s naked pose suggests submission when compared to Algis’s careless detachment. Despite their impending parenthood, Julie and Algis seem strangely disconnected, their roles unequal.

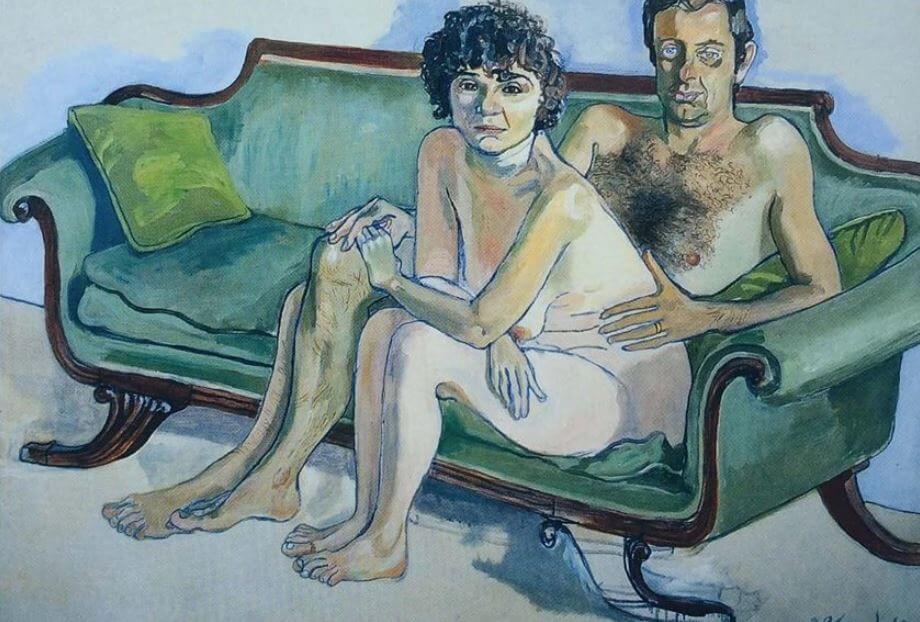

Painted seven years after Pregnant Julie and Algis, the portrait of Cindy Nemser and Chuck shows us a completely opposite dynamic in a relationship. Cindy hunches over to protect their modesty. Cindy Nemser and Chuck offers a vision of a relationship built on mutual respect. Neel persuaded her sitters to undress as she wanted to expose their characters. Cindy Nemser describes posing for Neel with these words:

I was petrified at the idea of being painted naked with my far from perfect body on display. At the same time, I also started to feel challenged by the whole situation. I decided to take the dare and risk exposing myself.

Cindy Nemser about posing for Alice Neel, in: Posing nude for Alice Neel, Cindy Nemser, Feminist Art Journal.

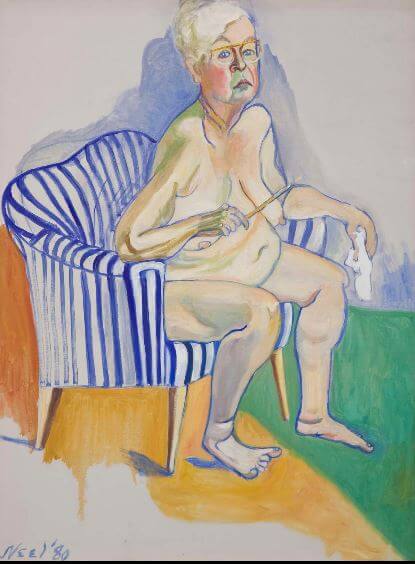

Neel’s last sitter for a nude portrait was no one but herself. Self-Portrait shows her at the age of 80. She sits completely naked with nothing but her glasses, paintbrush, and a rag in a familiar chair in her apartment. She has the same concentrated look on her face as she would have had when painting others. After breaking the taboo of painting pregnant mums-to-be, she broke the taboo of painting old women with this Self-Portrait as her life drew to a close.

Throughout her life, Neel dedicated her talent to painting honest representations of beauty in all stages of life. Unconventional, not just in her art but in her private life too, she never fit the boundaries society drew. Her interest in people never changed. In the beginning, Neel’s work reflected her experiences. As she aged, she focused her attention on other people but from the point of view of someone who was not shackled by society’s constraints.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!