Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

American Alice Neel painted portraits of one of her neighbors, Georgie Arce, from childhood through adolescence. These stunning images are as vivid and moving today as when they were painted in the 1950s.

I have tried to assert the dignity and eternal importance of the human being.

Interview by Mike Gold, Daily Worker Newspaper, 1950.

Speaking about Georgie Arce, Alice Neel said he was very smart, although he couldn’t read. They met when he asked to come and play with her dog. Over five years, Neel sketched and painted a series of works of this neighborhood boy and they remained friends for almost 30 years. However the ending to this story is heart-breaking. Let down by a chaotic, over-stretched and under-funded system, Georgie couldn’t extricate himself from the multiple deprivations of poverty within a racist society and he ended up in prison for murder.

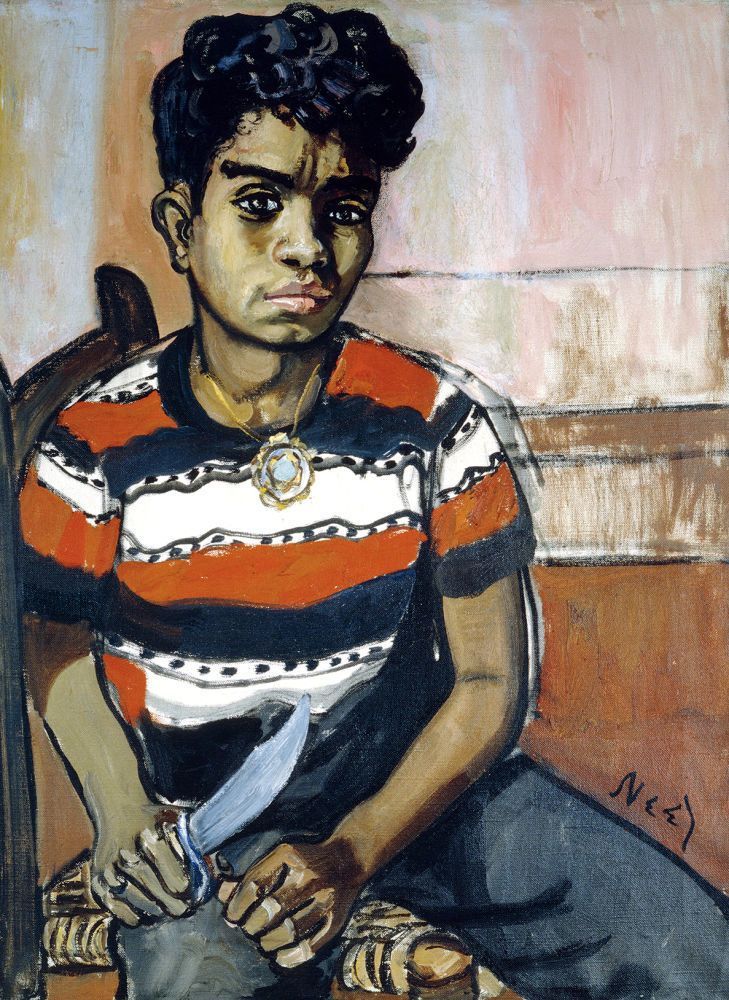

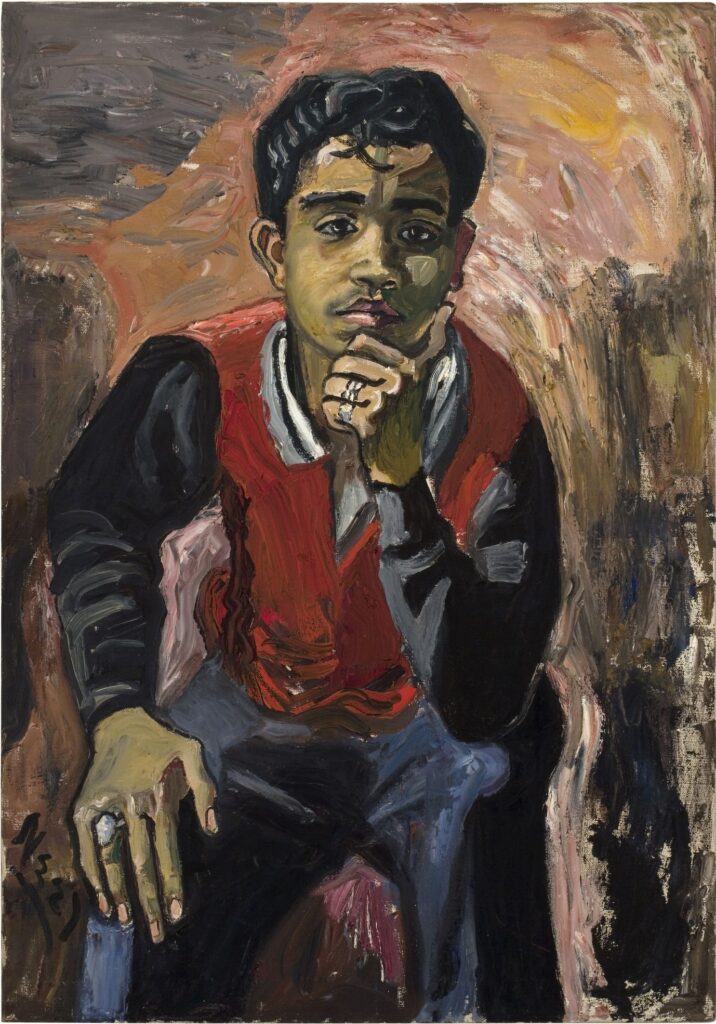

Alice Neel, Georgie Arce, 1953, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Neel gave dignity, identity, and power to her subjects. Look at how the expressive lines combined with the vibrant color palette produces a psychological intensity, as if we are in the room with Georgie. His features and expressions, his hair texture and his skin tones are sensitively brought to life. We are there for the fleeting thoughts and the possible future selves that occupy this young man’s mind. And we know Neel is present, looking with us at the humanity of this person. This is not an objective gaze, her sensitive depictions include her own response. It is almost a collaboration. Neel said this about her sitters:

I go so out of myself and into them that after they leave, I sometimes feel horrible. I feel like an untenanted house.

Phoebe Hoban, Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty, Saint Martin’s Press, USA, 2010.

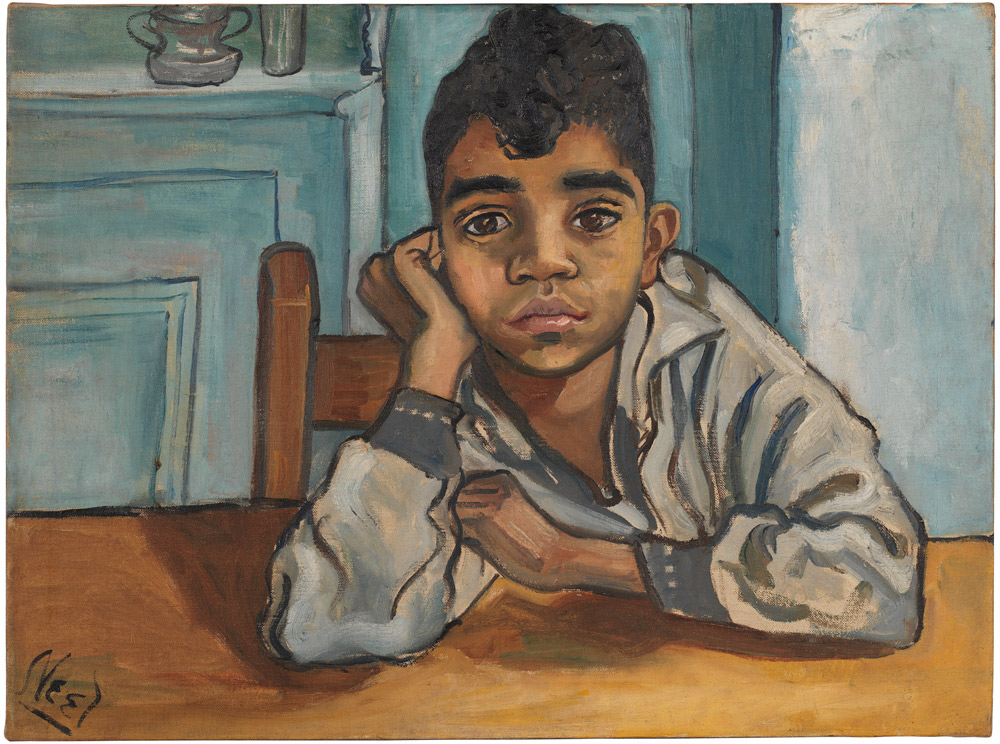

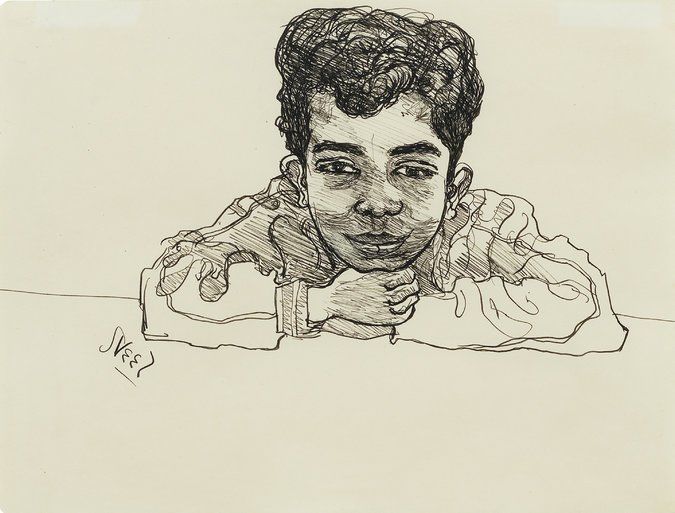

After meeting Neel and getting to play with her dog, Georgie Arce would run errands for the artist, then sitting for portraits. He appears in ink sketches and in oils and we watch him grow from child to teenager. Decades later, Arce would go to prison for murder, finally sucked into the violence that whirled chaotically around him from birth. Neel told the New York Times in 1976,

I paint to reveal the struggle, tragedy and joy of life.

Alice Neel, Georgie Arce no 2, 1955, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

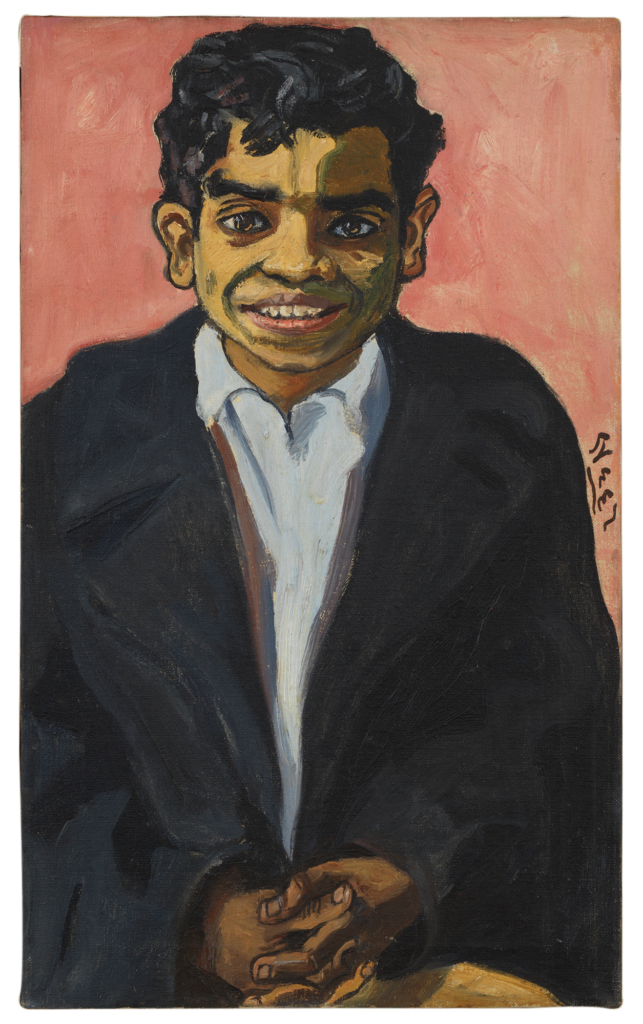

The early portraits of Arce show an engaged sweet young boy, but as time goes on, we see changes not only in his physicality – his broader shoulders for example, but also a more guarded gaze. In the painting where he holds a knife, we see his furrowed brow, his sullen eyes, his hands clenched, as he becomes an adolescent in a world which sees no value in him. His black hair contrasts against a hot-pink, earthy-brown background that has the shape and feel of a Rothko. In the final painting we see a resigned young man, challenging us to judge him, placed against a swirling and muddy background.

Even when he wields a knife, she captures his vulnerability, while respecting his boundaries: she never took from a sitter more than she was given… Did Neel think Black lives matter? You bet. She also saw people for who they were, not as stand-ins for one demographic or other.

“Alice Neel, our contemporary” in Apollo Magazine 3 April 2021.

Alice Neel, Spanish Boy (George Arce), 1955, Museum of the City of New York, New York, NY, USA.

A supporter of Marxist and Communist political thought, Neel painted images of activists demonstrating against fascism and racism. She showed America the impoverished victims of the Great Depression and her portraits were often of her very ordinary but fascinating neighbors in Spanish Harlem, New York. All of her work contains an honesty and a candor that is as shockingly beautiful now as it was then.

Whether I’m painting or not, I have this overweening interest in humanity. Even if I’m not working, I’m still analyzing people.

Phoebe Hoban, Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty, Saint Martin’s Press, USA, 2010.

Neel experienced more than her fair share of tragedy which gave her a keen and unflinching eye for the trauma and disappointment of others. She had deep compassion for those in pain. Her first daughter, Santillana, died of diphtheria before she reached one year old. Her second daughter, Isabetta, was abducted by her husband and taken to live in Cuba with his wealthy family. As a result, Neel had a breakdown and was hospitalized for a year. She attributed two suicide attempts not just to grief, but to extreme poverty. Various relationships with disturbed or abusive partners and two further children followed: Richard and Hartley. Here was a woman who could recognize and celebrate the imperfect. She had a sharp intellect and understood how anyone could fall into difficult circumstances.

Alice Neel, Georgie Arce, 1955, Estate of Alice Neel.

Neel moved to Spanish Harlem in 1930 and in her time there she completed hundreds of portraits of writers, poets, artists, singers, neighbors, friends, and family. She brought up her children in poverty and couldn’t afford a studio – instead she painted in her small apartment which was cramped with canvases. Neel was one of the first artists to be hired by the New Deal Works Progress Administration created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. She was obliged to produce one painting every six weeks. For this she looked out into her own community – she cast her compassionate eye on the poor, the ignored, the disenfranchised. When that money ran out she lived on welfare, handouts, and sometimes even shoplifting.

Alice Neel, Georgie Arce, 1955. The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London, Victoria Miro, London.

Throughout her career, Neel fought against social discrimination, striving to represent humanity realistically. She advocated for gay rights and spoke out against racial oppression. Her neighbors were Black, Latino, and South Asian. Few artists at the time were painting people of color and Neel’s portraits were generous and thankfully free of stereotype, caricature, and pity.

She painted people of color, the poor, the elderly, children, immigrants, gay and transgender people, workers, artists and political activists. She painted them naked and clothed, ailing and healthy, in Greenwich Village in the 1930s and later in Spanish Harlem and, from 1962 on, in West Harlem. She paid attention to them in ways that felt—and still feel—connected to love.

“Alice Neel’s Portraits Put People First” in Smithsonian Magazine, March 30 2021.

The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art has a fantastic exhibition guide about Neel that has a film of the artist discussing her work. It is obvious that she cares deeply about her subjects, who are, of course, her community. In the video primer she says:

I have never felt strange in East Harlem because of the fine and hospitable humanity I find all around me […] East Harlem is like a battlefield of humanism, and I am on the side of the people there.

Alice Neel, Georgie Arce, 1953, Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Haus Der Kunst, Munich, Germany.

Instinctive, dedicated, and uncompromising, Neel made visible the people mainstream white America wanted to remain hidden. Her portraits of black, Latino, or Asian New Yorkers were unique – unlike those of any other painter of her time. She gave the same consideration to her neighbors that earlier portrait painters had reserved for the great and the good, the Royals and the Presidents. Neel was quoted in a 1950 edition of the Daily Worker newspaper saying: “There isn’t much good portrait painting being done today and I think it is because with all this war, commercialism and fascism, human beings have been steadily marked down in value, despised, rejected and degraded.”

I love you Harlem

Your life your pregnant

Women, your relief lines

Outside the bank

What a treasure of goodness

And life shambles.Untitled Poem, 1950s

If you like the portraits, give a listen to The Ballad of Georgie by R.J. Philips Band, inspired by Alice Neel’s paintings!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!