The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

6 September 2024 min Read

All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me is a portrait, a memoir, almost a poem, written by Patrick Bringley about the ten years he spent as a museum guard. The book is about art, yes. It is about museums, yes. The book is a story about work, yes. But it is so much more!

If you have ever been curious about a museum’s behind-the-scenes action, then this book is for you. It is also for you if you have ever been curious about life, and how it works. Read on to find out how!

I was very excited about the opportunity to review All the Beauty in the World. The Met is one of my favorite museums, in one of my favorite cities, and Patrick Bringley spent almost every day of the 10 years that he worked there as a Museum Guard. Imagine getting to go to your favorite museum day after day after day! I was intrigued, curious about what inside stories a guard at The Met would be able to tell his readership, and ready to absorb all of the knowledge that would surely come my way after reading this book. I was in for so much more, though I did not know it then! But, let’s begin at the beginning.

Book Cover Image: All the Beauty in the World, The Metropolitan Museum and Me. Photo via Simon & Schuster.

The book is your standard hardback size, printed in those beautiful cream-colored pages that scream “New!” And “Read me!,” full of beautiful line-based illustrations that are reminiscent of both quick sketches and old engravings, both evocative and interesting at the same time. For all the word nerds and bookworms out there, the book has a very lovely biography and index of all artworks mentioned.

But, intriguingly, the book begins with a dedication to Tom. And, underneath this name, the Greek word ταλαίφρων. I am sad to say I do not know much Greek beyond Efcharistó and Kaliméra, but when I looked up this word in my translator, I learned that it means “Sufferers” in English. In Spanish, “Enfermos.” “The sick ones.” And so, the book begins. Already, I knew this memoir would take me on a journey beyond art. I just was not sure exactly where.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvesters, 1565, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

The book is divided into 13 chapters that take us through memorable works that Mr. Bringley learned to appreciate during his time at The Met. Some of these works are famous the world over, but some of them become endearing because of their meaning to the author: works like Raphael’s Madonna and Child Entombed with Saints, Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Harvesters, or Titian’s Venus and Adonis. Other works with which we are not so familiar, like the Cuxa Cloister, an 18th-century American mahogany work table, and an Aztec Water Deity. Mr. Bringley talks about them all with appreciation, with wonder, through experiences he has had alone, or in his interactions with both coworkers and patrons.

Head of a Water Deity (Chalchiuhtlicue), 15th–early 16th century, Mexico, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Throughout the book, we also come to know many singular locations in the museum—some of them places that the ordinary visitor never gets to see. Places like the Uniforms Office, where we learn there are tailors whose job is to ensure that all Museum Guards look their best day in and day out. Or the Command Center, full of monitors, that Mr. Bringley did not get to see clearly even once in the ten years he worked there. And we learn, for example, what happens when the museum is closed (see page 59, if you are curious).

Then there is the museum jargon that would baffle an outsider. Terms like “Post,” “Your relief,” or “the third platoon,” might not mean what we think they mean at The Met, and we get to read about it all firsthand.

Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, Christ in the Tomb and the Virgin, 1377, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

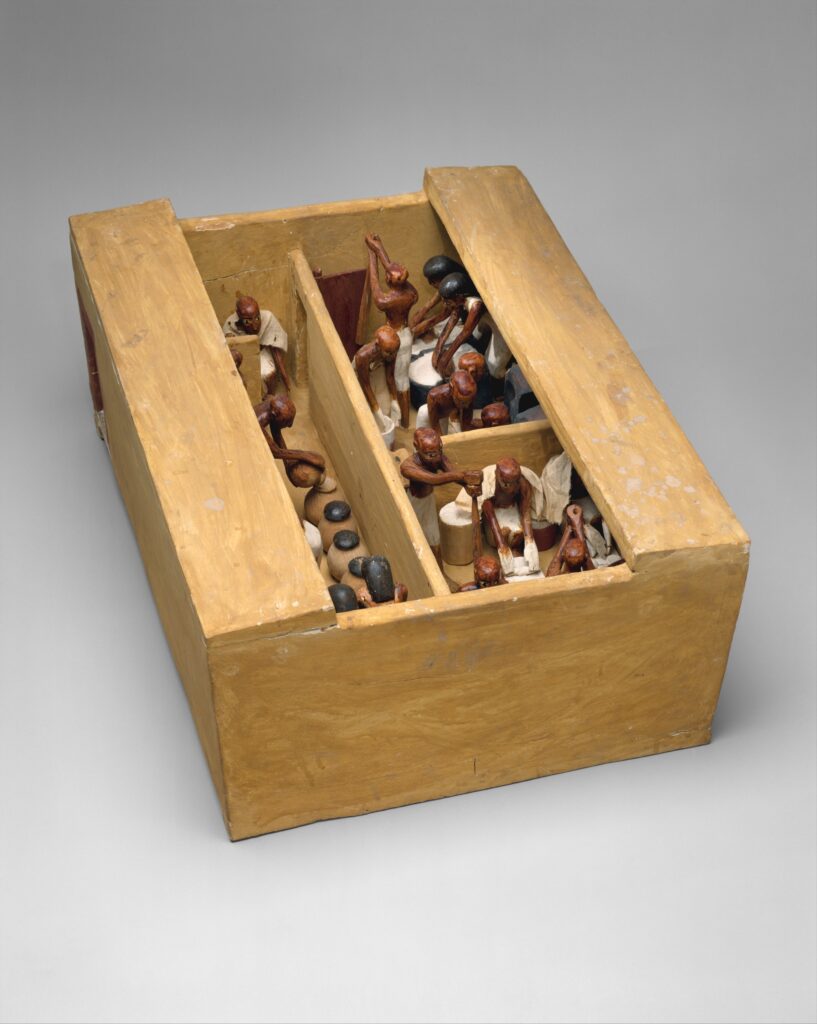

Mr. Bringley takes us through conversations with coworkers and trainees, and with both interested and disinterested Museum patrons. But, most of all, he takes us on a journey to understand why we look at art. Why, for example, a craftsman in Egypt took carving tools in hand to chisel out the 9-inch figurine of a brewer, or a baker. Or why, for example, Niccolò di Pietro Gerini added gold accents to his tempera depiction of the Deposition from the Cross in Christ in the Tomb and the Virgin. Why, you may ask?

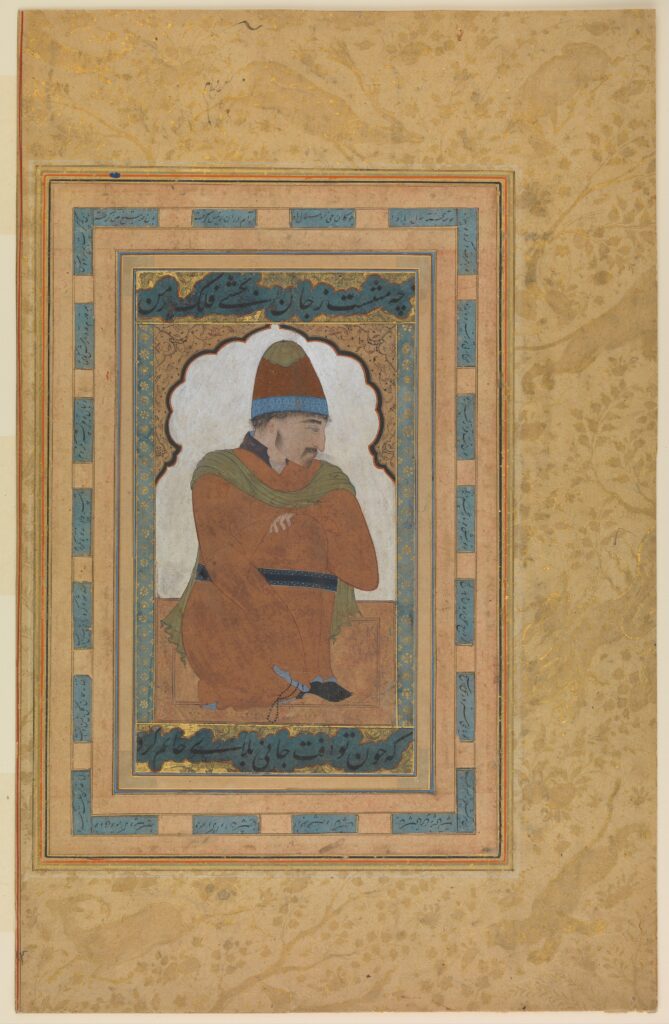

Portrait of a Dervish, Attributed to Present-day Uzbekistan, Bukhara, 16th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

The reasons are probably as varied as there are people out there. But, at the center of it all, it is because art gets to the heart of what makes us human. Very early on in the book—midway through the first chapter, in fact—we learn who Tom is. Tom is Mr. Bringley’s older brother. Towards the end of the first chapter, when Mr. Bringley’s first day at The Met is coming to an end, we learn that Tom got sick.

By that point, I started getting a hint of where the journey was going to take me and I wondered whether I was ready to go there. I have my griefs, too, you see. My mother passed away at the beginning of 2020. Even though I am an adult, and so was my mother, her passing has felt like such an uprooting. “Grief is among other things a loss of rhythm,” Mr. Bringley said.

Michelangelo’s last, incomplete sculpture: Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rondanini Pietà, 1564, Museo d’Arte Antica, Milan, Italy. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

I’m surprised by the meaning I begin to find in even small interactions with guards and visitors. A favor asked, an answer given, thanks proffered, welcomeness assured . . . There is a heartening rhythm to it that helps put me back in sync with the world. Grief is among other things a loss of rhythm. You lose someone, it puts a hole in your life, and for a time you huddle down in that hole. In coming to the Met, I saw an opportunity to conflate my hole with a grand cathedral, to linger in a place that seemed untouched by the rhythms of the everyday. But those rhythms have found me, and their invitations are alluring. It turns out I don’t wish to stay quiet and lonesome forever.

All the Beauty in the World, The Metropolitan Museum and Me (Simon & Schuster, 2023)

Mr. Bringley was in that journey—a journey of moving through grief and finding out what life looks like after upheaval.

. . . the atmosphere in the galleries was intensely familiar, though for reasons that had nothing to do with plaid skirts or severe nuns. It was the atmosphere of all those months at Tom’s bedside, one of speechless mystery, beauty, and pain.

All the Beauty in the World, The Metropolitan Museum and Me (Simon & Schuster, 2023)

Model Bakery and Brewery from the Tomb of Meketre, ca. 1981–1975 B.C., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

All the Beauty in the World puts us in the middle of that journey. The Old Masters, the Egyptian craftsmen, the Impressionists… just like all of them, we look at the world with eyes of wonder. They looked at the world, and were so moved that they had to leave a record of what they were seeing, of what they were feeling, to connect us to them through space and time, to connect us to each other. Just like that, the world we live in is beckoning us to see. And, when we see, to find beauty even when it seems like it is hidden. Even when it seems like there is no beauty to find.

I had lost someone. I did not wish to move on from that. In a sense I didn’t wish to move at all. In the Philadelphia Museum of Art [which the author had visited shortly after his brother’s passing], I had been allowed to dwell in silence, circling, pacing, returning, communing, lifting my eyes up to beautiful things and feeling sadness and sweetness only . . .

An idea was beginning to take shape in my mind. For years, I had noticed the men and women who worked inside New York’s great art museum. Not the curators hidden away in offices—the guards standing watchfully in every corner. Might I join them? Could it be as simple as that? Could there really be this loophole by which I could drop out of the forward-marching world and spend all day tarrying in an entirely beautiful one?

All the Beauty in the World, The Metropolitan Museum and Me (Simon & Schuster, 2023)

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1887, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

I learned many lessons during my journey through The Met as I read All the Beauty in the World. One thing was surprised me was that my lessons seemed to be quite different from those of others. I read many reviews and blurbs as I prepared to write my own and, for example, I was surprised that no reviews I read mentioned grief. Finding beauty through the grief had been such a theme for me, such an obvious, overarching theme, that I could not believe others had not found it there.

As I have thought about this more, I have realized that art is just like that. We might all be looking at the same piece, but we will not come out with the same exact conclusion. And that is the beauty of it! That is what makes art more of a conversation than a lecture—an amazing conversation across space and time. A conversation that breaks all barriers and gets straight to the heart.

If you have read this far, I think you should just get this book and read through it. You will find your own lessons. And, after you are done, maybe we can compare reactions! Some of the things I learned while reading encouraged me to examine my own approach to art, to life, which is ultimately all about connecting.

The Temple of Dendur, 10th century B.C.E., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

At the risk of being a little too repetitive, or too long-winded, here are twelve of the bits I liked best:

Fra Angelico (Guido di Pietro), The Crucifixion, ca. 1420-1423, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

All journeys come to an end. Eventually, Mr. Bringley’s time at The Met does too. The final chapter of the book is called “All That I Can Carry.” It is an excellent title for the last chapter of a book that says so much in only 178 pages of text. There, the author invites the reader to,

Find out what you love in the Met, what you learn from, and what you can use as fuel, and venture back into the world carrying something with you…

All the Beauty in the World, The Metropolitan Museum and Me (Simon & Schuster, 2023)

The idea of it all had been to find a way to drop out of the forward-marching world and “spend all day tarrying in an entirely beautiful one.” It was this journey of looking at art and back into looking at his own self, that allowed the author to move through his own quest. And, just like Joseph Campbell’s hero, he returned to the world to share the elixir with us. Unlike art, we cannot stay in one moment forever. But these artful moments provide the solace we all need for the road ahead, for venturing out into the world again.

Yes. That beautiful world is there. It was there for him, and it is there for all of us.

Here are the usual stats:

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!