5 Contemporary Women Artists from Latin America You Need to Know

When we speak about contemporary art in Latin America, women artists are at the center stage. Working around various mediums and highlighting themes...

Natalia Tiberio 16 December 2024

Artisans in pre-Columbian and colonial Mexico, as in Peru, used feathers to create exquisite adornments for nobles, fancy textiles for the elite, and provided feather embellishments for the shields and military costumes of the warriors. It wasn’t camp; it was all about vogue, status, and luxury.

The feather works were definitely statement pieces. But, as much as they were about Mesoamerican or Incan bling, they reveal a special nature-driven fascination with the regional color, a technique still experienced with modern and contemporary Latin American artists such as Rufino Tamayo, Francisco Toledo, Jesús Rafael Soto, Tarsila do Amaral, and Carlos Cruz Diez.

Before and after the Spanish conquest, indigenous craftsmen employed these natural expensive materials (more valued than gold or silver) to produce vibrant, symbolic, and unique art pieces that have been preserved through time in excellent shape and form.

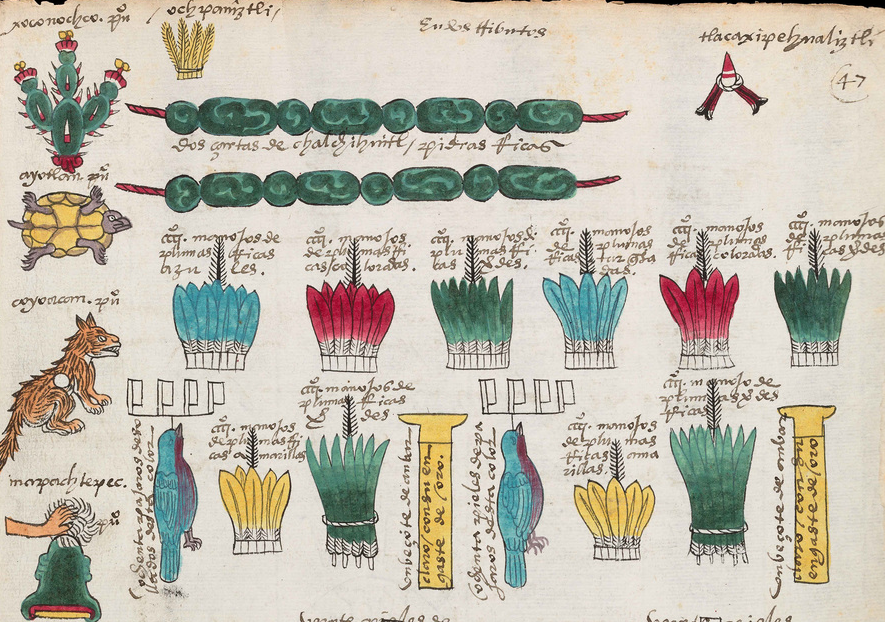

Overall, the most common feathers used by those craftsmens (as mentioned in the documentary sources) were quetzal (quetzalli), scarlet macaw (alo), roseate spoonbill (tlauhquechol), Mexican trogon or green parakeet (tzinitzcan), lovely cotinga (xiuhtototl), yellow-headed parrot or an oropendula (toztli), heron (aztatl), and eagle (quauhtli).

The Mexica ruler Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (1502-1520) maintained an aviary (which housed eagles, roseate spoonbills, troupials, yellow parrots, parakeets, large parrots, and pheasants, at least) along with a stable of royally-employed feather workers. In Tenochtitlan, feather workers belonged to a particular social class. They lived in a neighborhood called Amantla, which is why they were called amanteca.

These very skillful artists must have been fascinated by the powerful colors invented by nature. They trimmed and applied plumes on cloth or wood. They created very geometric, almost modern-like works, or, made pictures imitating life, full of detail, applying feathers as they would paint.

The demand for feathers was enormous and constant. They were supplied by traders and as part of the tribute by the surrendered tribes to the governing elite. They were exported from Central America to Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) in the case of Mesoamerica, and from the Amazon to the Andes (Cuzco, Lima).

They were received in varying forms: as whole birds, raw feathers of the head, neck, back, and breast, or as featherwork objects. In the Codex Mendoza, we find specifications about the quantities, which gives an idea of how many birds were caught for art and crafts. A measure applied was a handful, so in the case of the smaller birds, such as trogons and a yellow-crested parrot, one animal gives 7-8 handfuls. If 8,000 handfuls were required, this meant that over 1,000 birds annually needed to be killed.

Feathers are organic materials, associated with the divine, heavenly, and supernatural forces, and were precious and hard to acquire at that time. Their value came both from cultural associations as well as their origin. So, how did the artisans of Peru and Mexico use them?

For the Andean and Mesoamerican artists, feathers were a source of diverse and rich colors. They didn’t have the variety of pigments necessary to create paint or comparable mediums to create outstanding and valuable objects. At the same time, they must have enjoyed, as we now do, looking at the beautiful creatures that lived in the surrounding forests. The blues, yellows, oranges, deep and soft pinks, greens, blacks, and grey with a hint of blue that covered birds were mind-blowing, vivid, and diverse. They enabled the craftsmen to create masterpieces whose intense, rich color has survived to this day.

The objects from the Andean cultures were more geometrized. The patterns, schemes, and rhythms of colors and shapes dominated the visual language of the Wari, Nazca, and Chimu cultures. Some are very abstract, others refer to natural animal shapes.

A similar composition we can find in the tabard with pelicans, wherein two rows of two big pelicans are carried by smaller ones. Here, the artist cut and trimmed individual feathers to heighten the outlines of each pair of birds. With a slit in the middle for the head, such garments would have been donned by high-status men.

The Andean artisans also designed very abstract, insanely modern-looking layouts, as shown in two other works below. The first composition is made of twelve feather panels, made by the Wari people of southern Peru between about 600 and 1000. These panels were produced with a cotton cloth and small iridescent body feathers of the blue and yellow macaw. When juxtaposed, the neatness of the rectangles, the rhythm, and the symmetry, are all stupefying. Thousands of feathers were used to produce this image, with each individually hand-knotted onto cotton strings and subsequently stitched.

The orange tabard, from the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, is a clothing item, like a tunic, but with no side seams. Seen here is another abstract composition, with a largely orange surface, and an arrangement of yellow and green rectangles. The element of symmetry is kept; there are four green rectangles on each side, varying in size. The artisans of Peru clearly showed an enchantment with the rich and vibrant colors of the birds. They translated it into different works: some with purely decorative or ritual functions; some with more practical use. They also displayed great craftsmanship mandated by a very fragile medium. Lastly, they exhibited a preoccupation and attention to design, abstract aesthetics, and geometry.

Probably the most famous featherwork is a headdress from Mexico known as the Penacho of Moctezuma II. It can be seen in the Museum of Ethnology, Vienna. The original iridescent crown, traditionally recognized as a headpiece worn by the last Aztec king Moctezuma II, is 116 cm high and 175 cm wide. The smallest inner circle is made from blue feathers of the Cotinga amabilis. The next layer is made of roseate spoonbill feathers. The next, small quetzal feathers following a layer of white-tipped red-brown feathers of the squirrel cuckoo, Piaya cayana. The longest feathers came from the quetzal, a bird that lives in the montane cloud forest, in the region that spreads from Southern Mexico to western Panama. They are 55 cm long.

Quetzal feathers have unique features: iridescent, and appearing blue from some angles and green from others, they often shimmer with a golden overlay.

Yet, the quetzal wasn’t the only commodity of this type. Highly sought in Mesoamerica were hummingbirds and ocellated turkeys for their similar characteristic iridescent feathers. Because they reflect light and leave a radiant effect, they were used to adorn the head of a king, to mark his status, to make him bigger, and more importantly, to emphasize and enhance his divine nature.

The shimmering feathers were also used to paint Portrait of Christ. Its author Juan Bautista Cuiris used hummingbird feathers around the head of Jesus, with yellow parrot feathers marking the halo. The idea is pretty much the same as in the Moctezuma headdress, where gold circles were next to the forehead and quetzal feathers formed the second aureole. The artist made the same visual parallel to communicate the concept of spirituality and divinity.

This is an example of artworks called “hybrid” and tequitqui, made at the workshop in Pátzcuaro, in the state of Michoacan. Many of these kinds of works were made after the Spaniards colonized Mexico, the traditional feather craft was reemployed in the Christianization effort. Again the most precious and rare material was used to depict the most cherished aspects of Christianity.

The artistry of these objects is unquestionable: they combine European styles, and topics- sometimes a composition using old techniques and an eye for the natural color and texture of the medium

The ancient context of feathered works is often hidden. Historians, experts, and scientists suspect different functions: ritual- or status-oriented. We cannot be absolutely certain how they were used and what for. But, we can certainly appreciate the indelible impact they represent. The ingenious talent of these Mesoamerica and Andean artists, to mix and juxtapose different colors and textures, left us with objects that continue to bring joy and amazement.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!