Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

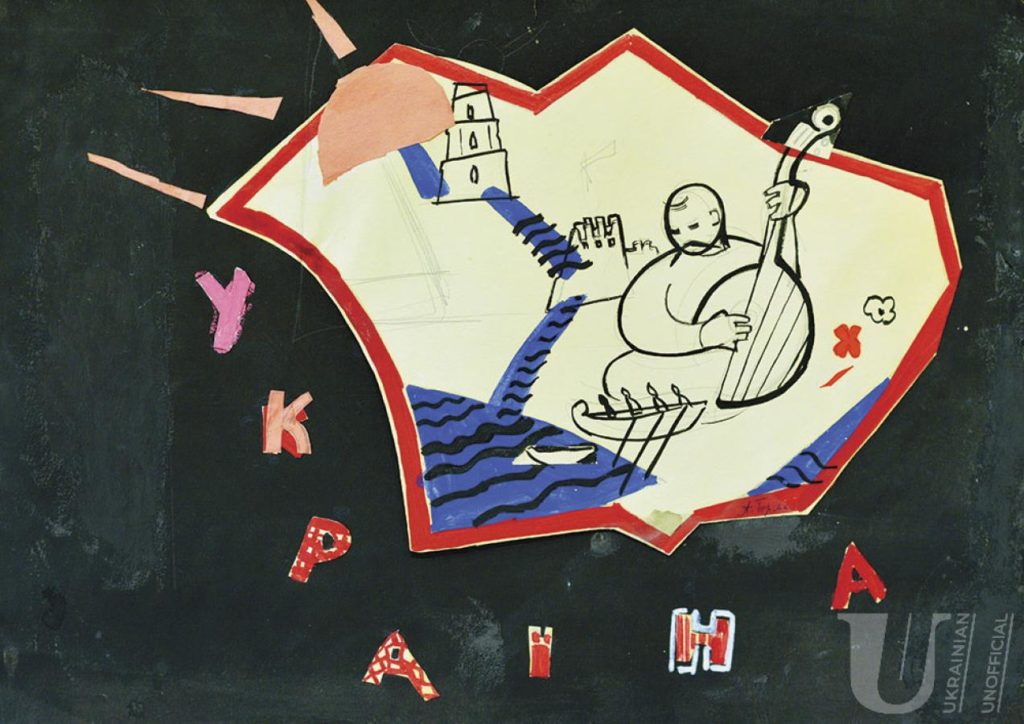

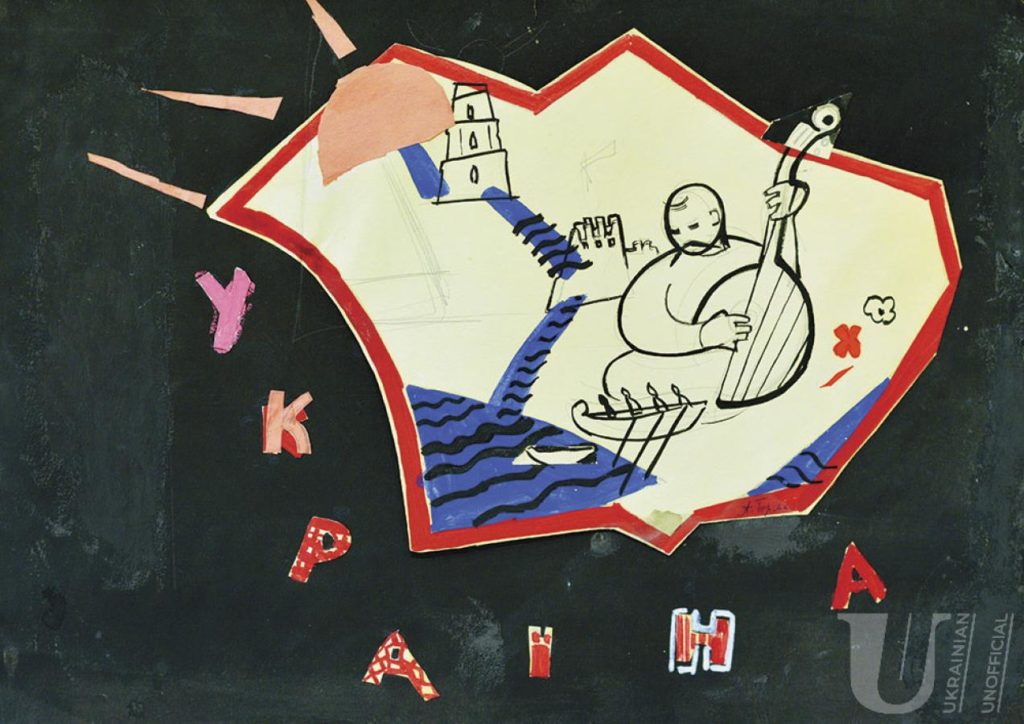

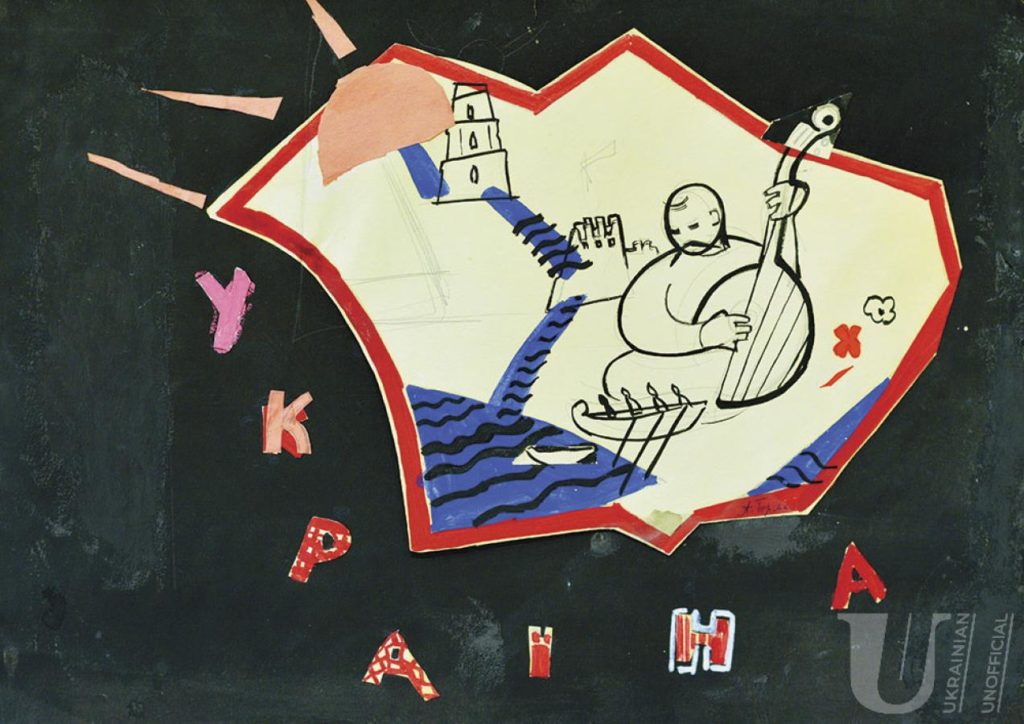

Ukrainian artist Alla Horska created dozens of amazing mosaics and paintings while actively fighting against the crimes of the Soviet authorities against the intelligentsia. For this reason, she has often been called “The Soul of the Sixtiers”.

Alla Horska belonged to the Sixtiers ( or Shistdesiatnyky ). This is a name given in Ukraine to the 1960s group of artists who reject the principles of social realism with their creativity and refused to let their artworks (paintings, poems, plays, etc.) serve the interests of the Soviet authorities.

Socialist Realism is an art movement that declared a world-view concept of a socialist society. The art conceived in this specific style was strongly influenced by the political requirements – the artists were forced to use codified forms and artistic language required by the authorities. There was very little space left for any artistic diversity, free aesthetics, or high uniqueness of the paintings or poems. Art became formulaic because it had only one function – to serve the interests of the authority.

The Sixtiers were part of the dissident movement. They would assert not only the right for freedom in artistic creativity and its very identity but also advocate the development of the Ukrainian language and culture as a whole. Therefore, this group of artists laid the foundations for the realization of the rights of the Ukrainian people to their own statehood.

The idea of the Sixtiers is a counter-cultural phenomenon that is opposed to official authority. The Soviet authorities did not forgive this. It was not just about banning creative activity in public; in some cases, everything was much more serious. The Sixtiers were followed, summoned for questioning, arrested, and often sent to the penal colonies. Ones considered disobedient were usually killed.

Alla Horska was fearless. Her bravery did not only manifest in art. She was one of the creators and developers of the centers of national life. Together with Vasyl Stus, Vasyl Simonenko, and Ivan Svitlychny, she founded the Creative Youth Club Contemporary in Kyiv in 1960. Together, they exhibited paintings, performed plays, read poems, and mentioned everyone and everything that was stamped out by the Soviet authorities. Ukrainian culture and history were created there.

After the artist and other dissidents discovered a mass grave in Bykivnia in the Kyiv region in 1962 (referring to the victims of NKVD), Alla Horska’s human rights activity quickened in pace. She participated in protests. Political prisoners asked her for help, and dissidents often found shelter in her apartment. All of this resulted in an appeal to the Soviet authorities with a Letter of Protest of 139 calling to stop the persecution, Alla Horska also signed it.

Of course, neither artistic nor the human rights activities of Horska could stay unnoticed by the authorities. The artist’s apartment was watched; her phone was tapped, and her every step was monitored. She was repeatedly questioned by the KGB and unsuccessfully “recruited” to their ranks.

Horska and her entourage were preparing to be arrested sooner or later. The artist was not scared, and she continued to do her best to protect Ukrainian culture and the people who worked to create it. But no one was ready for what happened next – Horska was brutally murdered. A full investigation was never done, and the case was labeled as domestic violence. However, there were many inconsistencies in the case to indicate that it had been fabricated. Both Horska’s family and her social group were certain that her murder was conducted by the KGB.

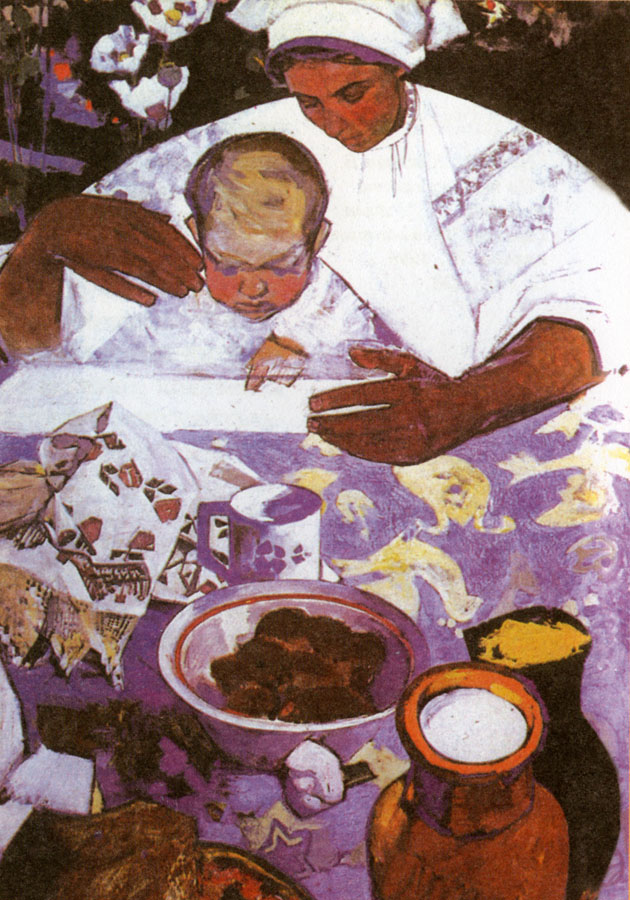

Of course, like many artists at the time, Alla Horska started her artistic career by creating artworks that actually fit the Regime’s aesthetic. But even in the beginning we can see that it was never about blind obedience and following the prescription of drawing party officials and happy youth propaganda, her works were always intimate and filled with love.

In her early artworks, she worked with the topics of mining work and created paintings that fit the Soviet coordinate system.

But, as time went on, the artist was more enchanted with the spirit and ideas of genuine Ukrainian culture. Of course, the Soviet authorities liked this much less.

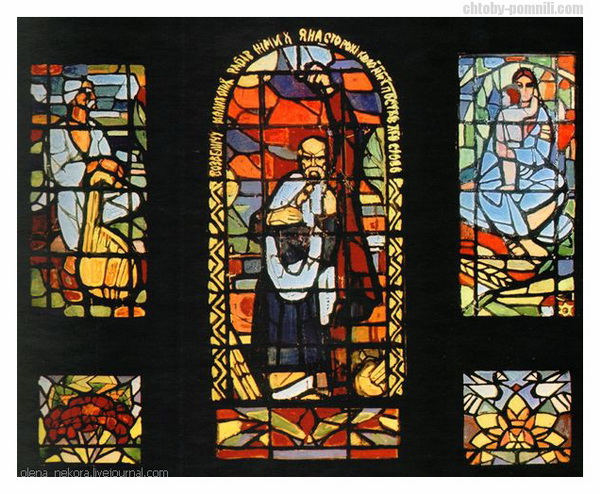

As an example, in 1964, together with other artists, Horska created a stained glass window, Shevchenko. Mother, in the foyer of Kyiv University. Taras Shevchenko is a Ukrainian poet of the 19th century and became a symbol of the struggle for freedom of the Ukrainian people. The artwork was found to be ideologically hostile and has been destroyed. As a result, Horska was expelled from the Union of Artists. Although she would renew for membership for a year; she would be, however, expelled again.

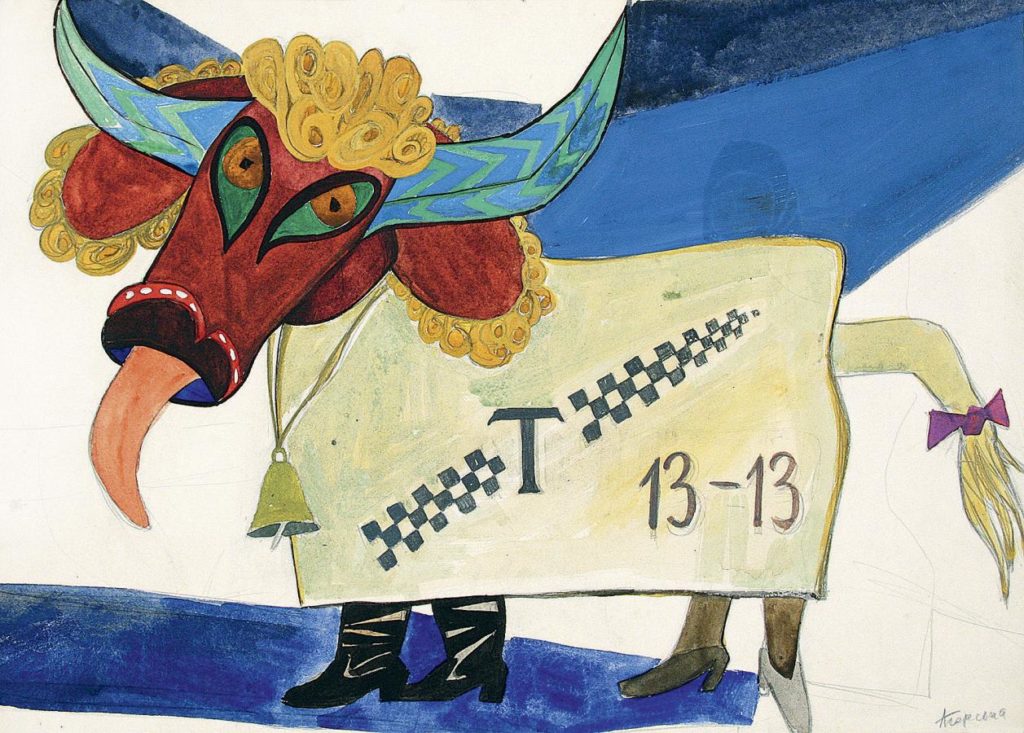

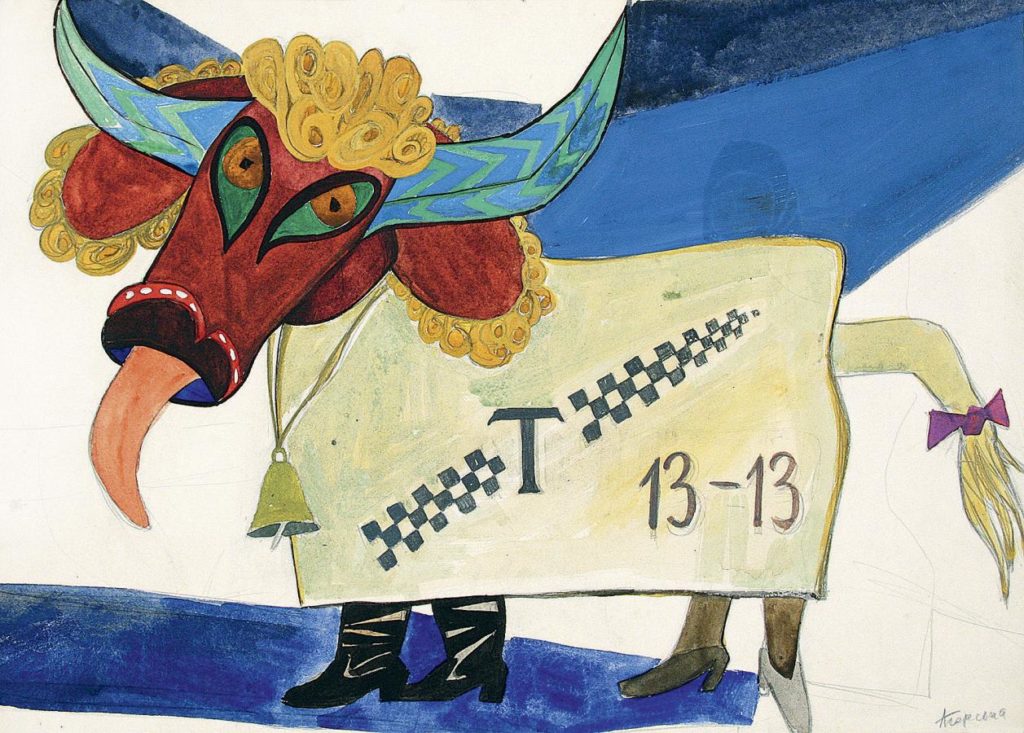

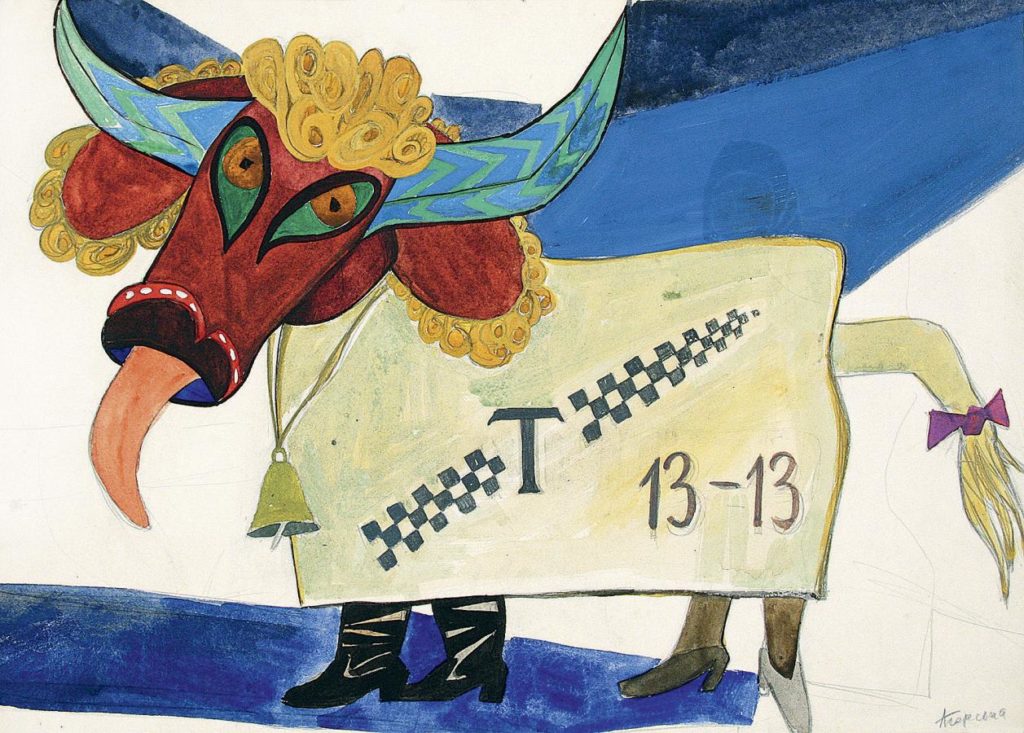

In collaboration with other artists, Horska created dozens of fantasy mosaics.

They shine with bright colors and show simple, but charming plots. As can be seen, they include many beautiful birds and trees, fantastic fish and beasts, radiant sun, and swirling wind. However, many ideas for mosaics stayed as sketches or were destroyed by Soviet forces. Unfortunately, the fate of some mosaics is now unknown due to the fact that many of those are located in cities that are being heavily bombed by Russian military forces.

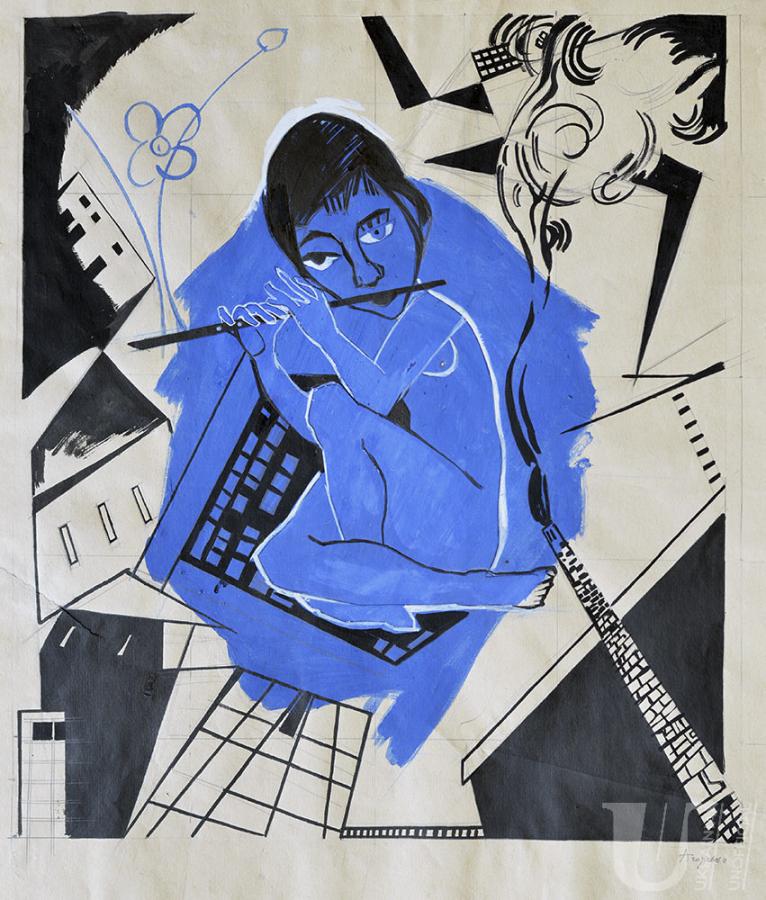

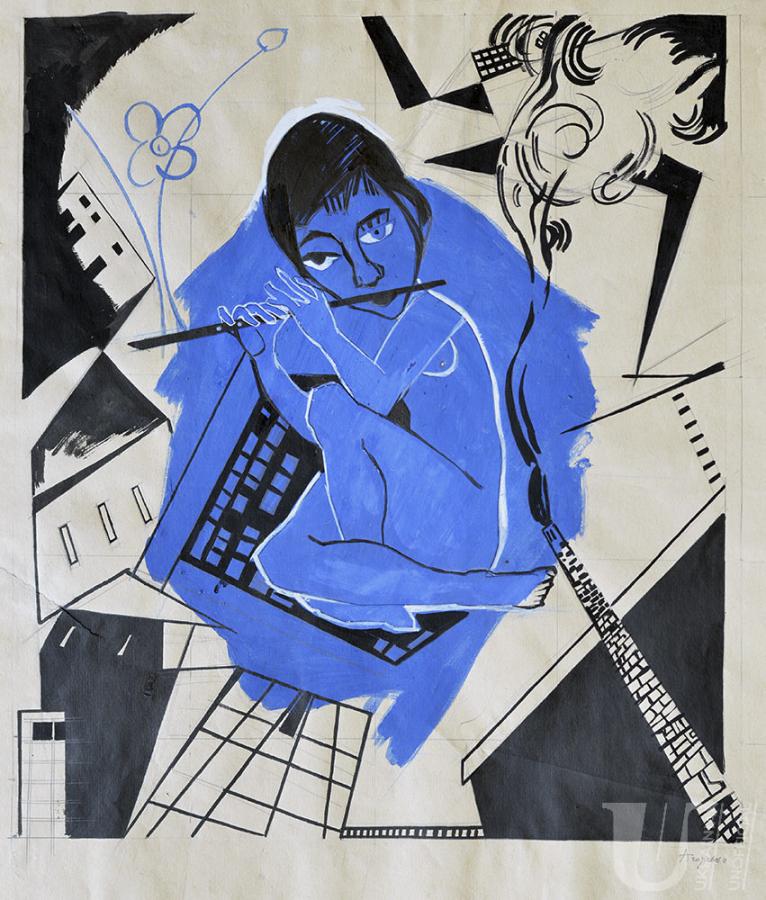

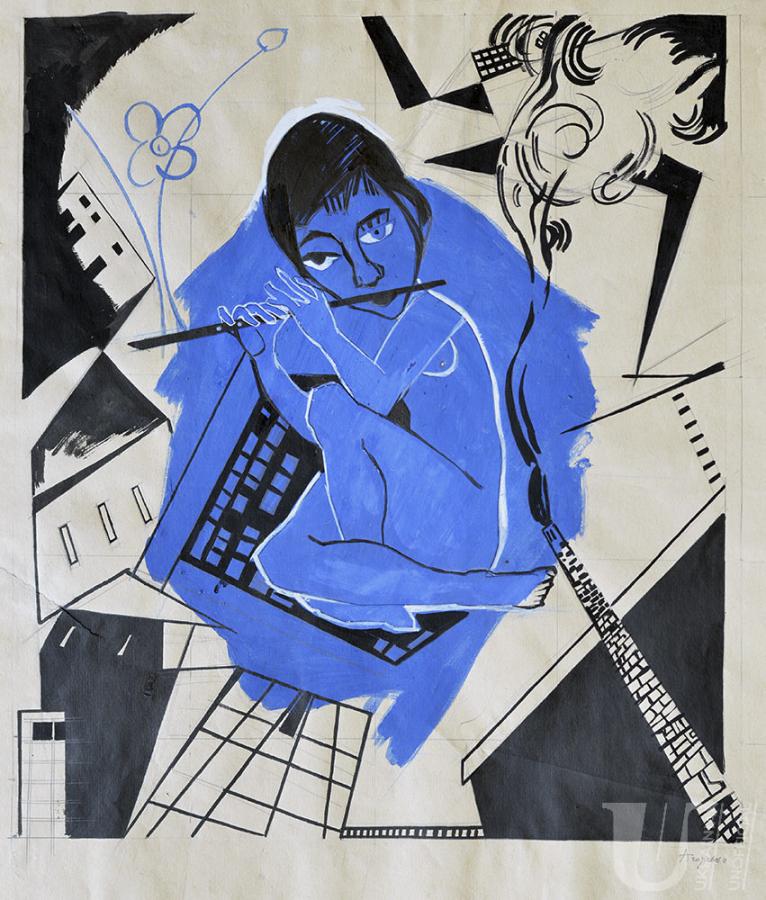

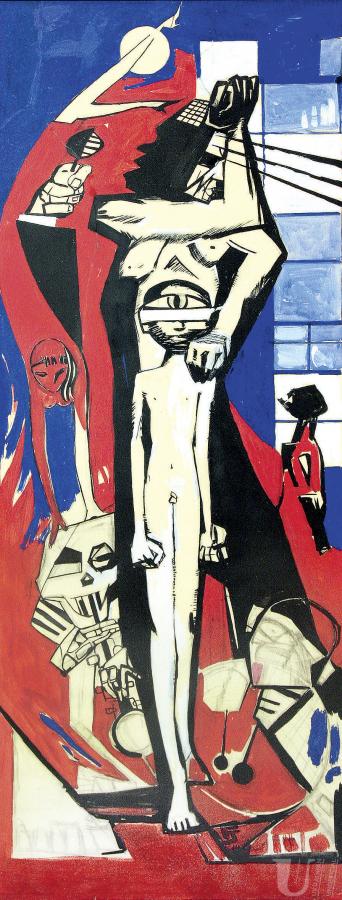

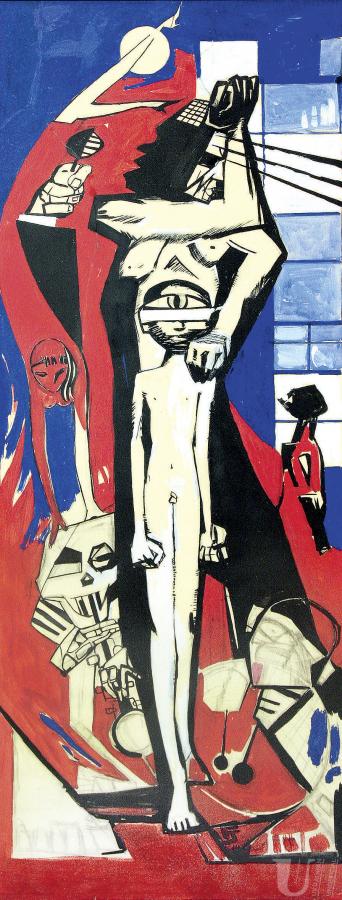

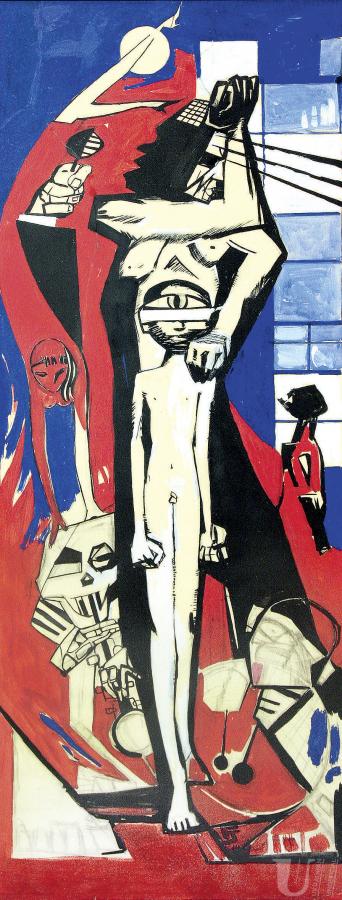

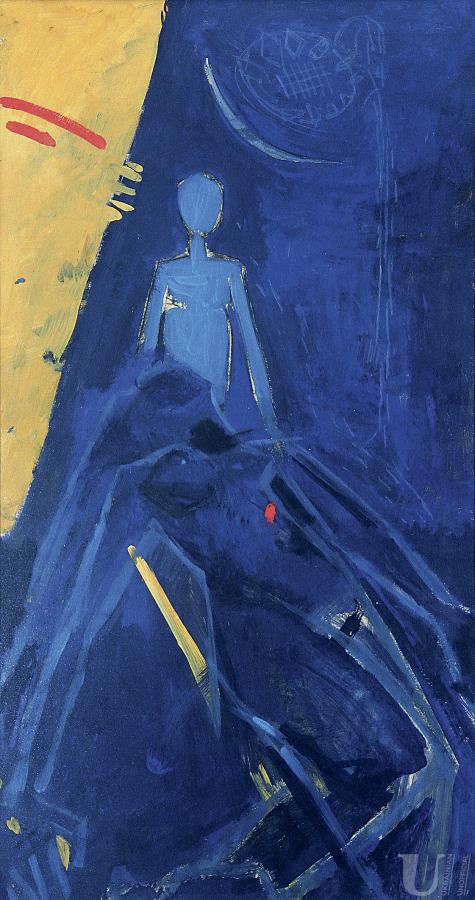

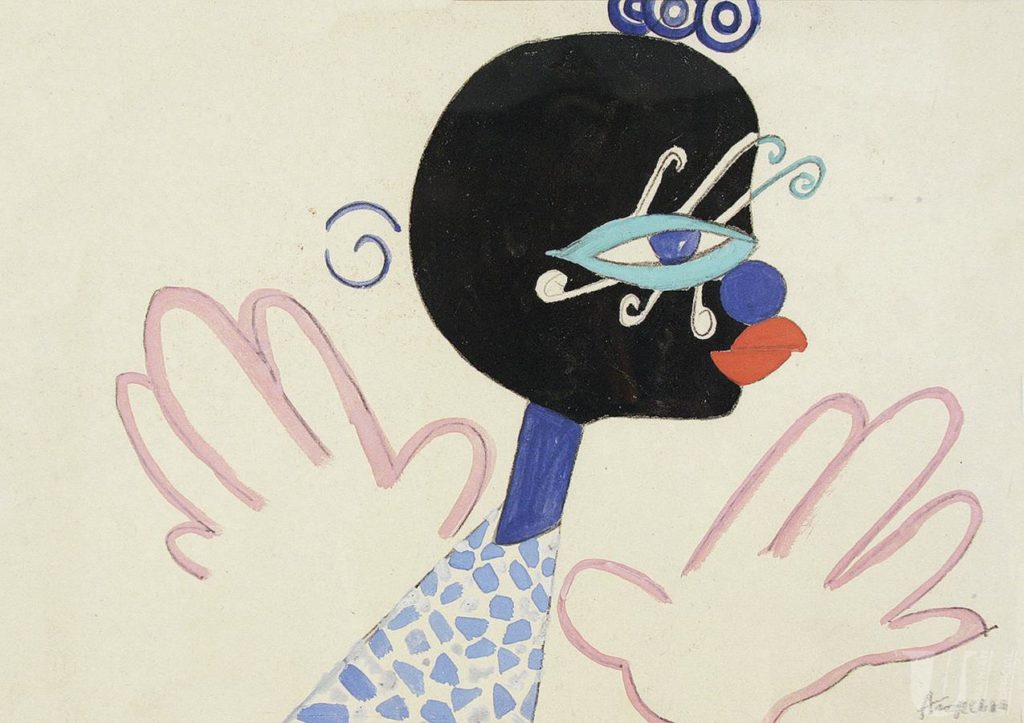

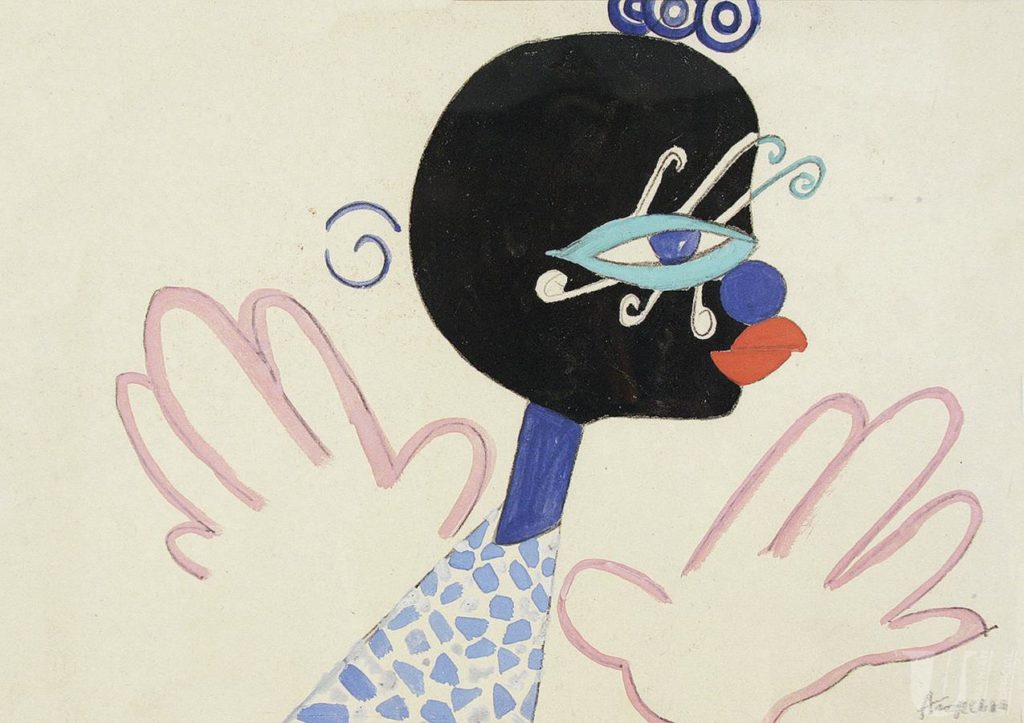

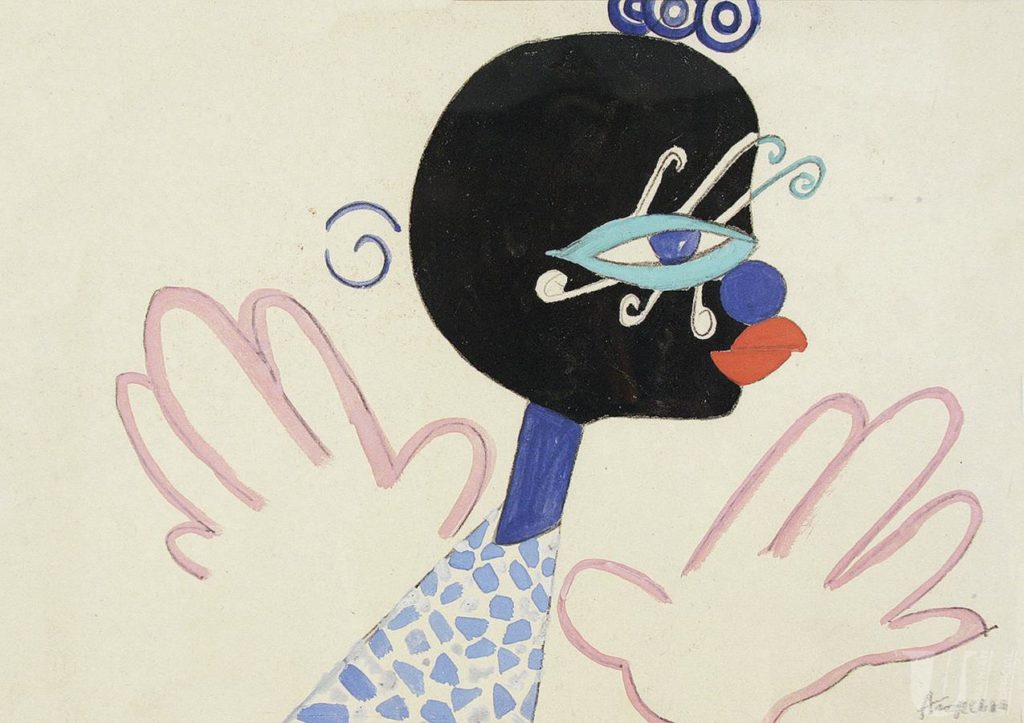

In her paintings, Horska completely distances herself from the ideas of Socialist Realism. Her canvases breathe with Avant-Garde, which was a genre outside of the official art.

Alla Horska was only 41 when her life was tragically cut short. She left behind a husband and a young son.

Her funeral on December 7, 1970, turned into a civil resistance campaign. Her associates – the literary critic Yevgen Sverstiuk, poet Vasyl Stus, human rights advocate Ivan Gel, and civil activist Oles Sergienko made speeches. The event was not allowed by the investigative commission and all of those who spoke were arrested a short time later. Two years after the death of the artist, mass arrests began among the Ukrainian intelligentsia. As a result, for some, it was the beginning of the end. For example, the literary critic Ivan Svitlychny and the poet Vasyl Stus were both arrested, and both of their lives ended as a direct result of Soviet imprisonment.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!