Masterpiece Story: The Climax by Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley’s legacy endures, etched into the contours of the Art Nouveau movement. His distinctive style, marked by grotesque imagery and...

Lisa Scalone 27 October 2024

Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939) is the most iconic Art Nouveau artist. His works featuring beautiful women surrounded by nature are still popular today. He achieved great success in France but he never let go of his Czech roots. Regardless of how far away he was, he remained interested in the political developments of his nation and other Slavic ones. Moreover, he participated in many projects to help construct a Czech national identity and to support pan-Slavism. Let us review some of Mucha’s pan-Slavic posters to see how his artistic and political interests merged.

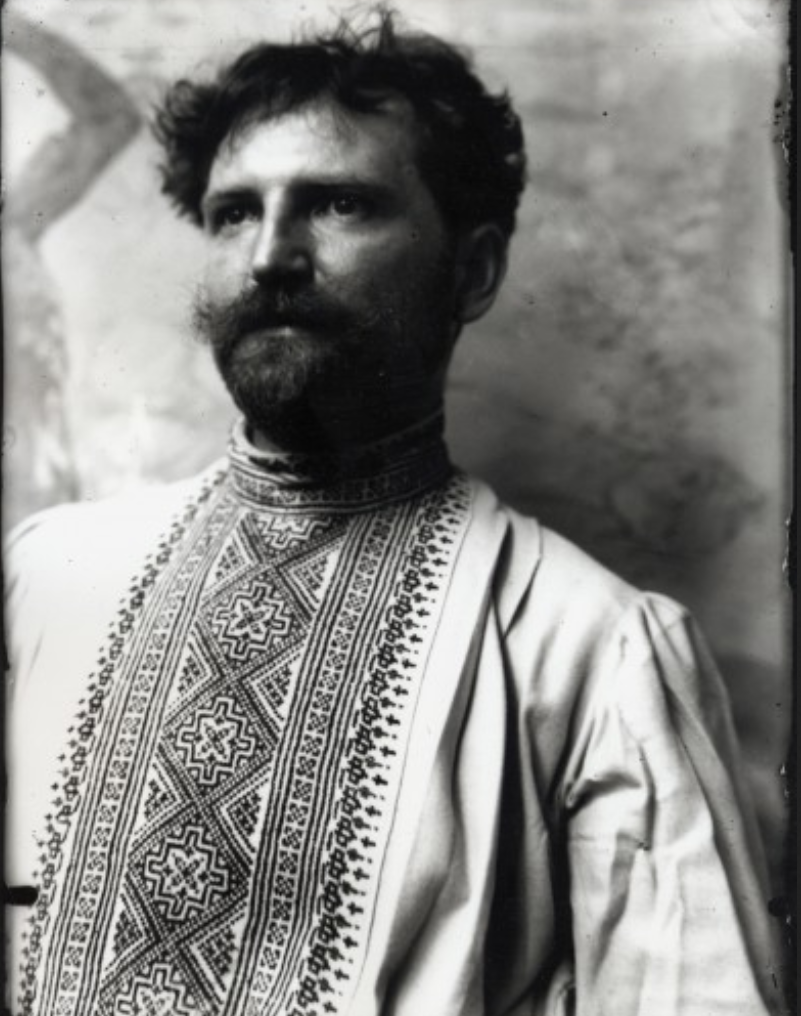

Alphonse Mucha, Self-portrait in a Russian shirt ‘rubashka’, in the studio, Rue de la Grande Chaumière, Paris, 1890s. Mucha Foundation.

Pan-Slavism was a movement that originated in the 19th century. It refers to the union of all Slavic peoples in Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe. The purpose was to reinvigorate each of these cultures meanwhile also uniting them for their similarities. It was a way of protecting their cultures from the larger empires to which they belonged. At first it was a cultural effort, but during the second half of the century, they moved towards independence. For this they turned to arts and culture, as they have always been an effective tool for propaganda. According to Erin Dusza, “Mucha provided a visual embodiment” of the ideas of pan-Slavism.

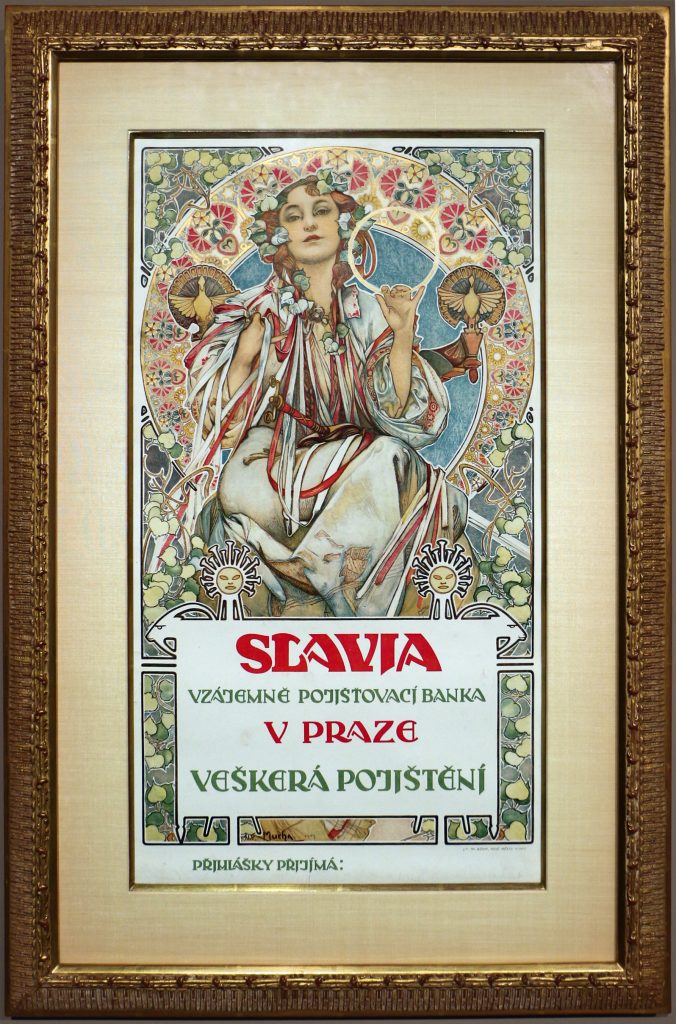

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for Slavia Mutual Insurance Bank, 1907. Photograph by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons.

Alphonse Mucha was a Czech artist who traveled to France in 1887. There he achieved great success through his commercial and theatrical posters. However he never lost touch with his homeland and the pan-Slavic movement. He read the writings of his compatriots, such as Jan Kollár and Frantisek Palacký, and studied the history of his people. In 1900, he worked on the Bosnia and Herzegovina pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris.

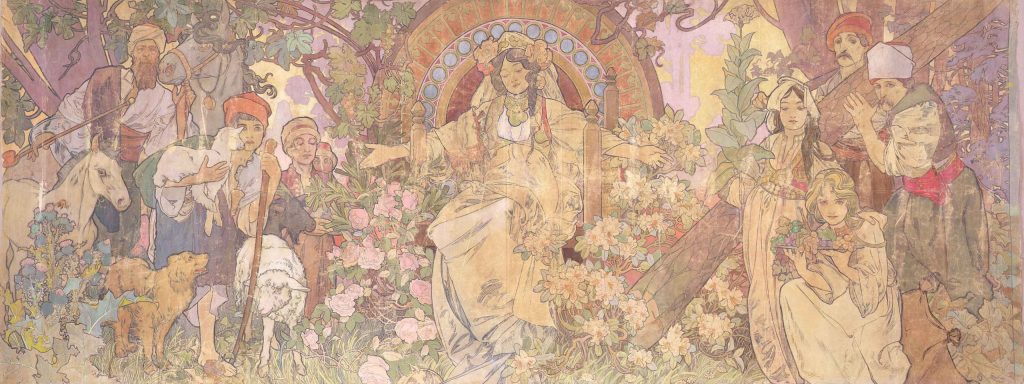

Alphonse Mucha, Allegory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1900, Musée du Petit Palais, Paris, France. Mucha Foundation.

Ironically, this commission came from the Austrian Empire. That is why he worked on the poster for its pavilion as well. Mucha saw this as an opportunity and he traveled to the Balkans to see the landscape and people. Furthermore, it inspired him to go back home and do more for the cause.

Left: Alphonse Mucha, Poster for the Austrian Pavilion at the Paris Exhibition 1900, 1900, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ, USA. Right: Alphonse Mucha, Menu for the Bosnian Pavilion Restaurant at the Paris Exhibition 1900, 1900. Photograph by SiefkinDR via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1910, he returned to Moravia and worked on projects that highlighted Slavic and Czech culture. He made the poster below for the Regional Exhibition at Ivančice, his hometown. To identify it, he included the Assumption of the Virgin Mary Parish Church. Another notable characteristic is the use of red and white, which along with blue are the pan-Slavic colors. For this reason, many of the current flags of these countries have them. Therefore, in one poster Mucha could showcase his town and the larger transnational movement he supported.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘Regional Exhibition at Ivančice 1913’, 1912, Mucha Museum, Prague, Czech Republic.

It is important to note that the Austrian Empire conducted campaigns of Germanization which prompted the Czechs to reject any trace of German influence. Therefore, they focused on their national art, their own folk songs, and stories. Moreover, they built theaters, museums, and art schools to educate future generations. Mucha worked with many of them. For instance, he made a poster for the Moravian Teachers’ Choir, a famous group that played Moravian folk songs and works by Leoš Janáček, influenced by Slavic folk music. The same year, he did a poster for Oskar Nedbal’s Princess Hyacinth.

Left: Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘Moravian Teachers’ Choir’, 1911, Mucha Museum, Prague, Czech Republic. Right: Alphonse Mucha, Princess Hyacinth, 1911, Mucha Museum, Prague, Czech Republic.

Since his time in France, Mucha’s posters featured personifications of seasons, arts, flowers, precious stones, and others. In 1908 he made another version requested by Richard Crane, who financed his biggest artwork, The Slav Epic.

Alphonse Mucha, Portrait of Josephine Crane-Bradley as Slavia, 1908. National Gallery Prague, Prague, Czech Republic.

Here are more of them.

Now, one may wonder if Mucha’s art in Moravia continued to be Art Nouveau. We typically think of this movement as a French one and associate it with commercial purposes and decorative objects. In reality it manifested in other countries and each of them made it their own. More importantly, Mucha always considered his style to be “Slavonic”. As mentioned before, he studied the history of the Slavs, for which he included Byzantine, Celtic, and folk elements. So, even when he was doing posters for Nestle, he considered them Slavonic.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘Nestlé’s Food for Infants’, 1897. Mucha Foundation.

Last but not least, the following posters announced Mucha’s greatest project: the Slav Epic. This was a series of 20 monumental paintings narrating the history of the Slavs since their mythic origin. It was not a commission, this was a personal project. He worked on it for 18 years, from 1910 to 1928. This poster marks the first exhibition of the entire work. The multifaceted figure is Svantovit, the pagan Czech god of destiny.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘The Slav Epic Exhibition, Brno, 1930’, 1926, tempera on canvas, Moravský Krumlov Chateau, Moravský Krumlov, Czech Republic.

Moreover, Mucha used his daughter as a model for the woman in the front. The same image appears in The Oath of Omladina under the Slavic Linden Tree, the 18th piece of the series.

Alphonse Mucha, The Oath of Omladina under the Slavic Linden Tree, 1928-1930. Google Arts & Culture.

So, there they are, some of Mucha’s pan-Slavic posters. They are a testament to his commitment to the cause to protect the Slavic cultures.

Erin Dusza: Epic Significance: Placing Alphonse Mucha’s Czech Art in the Context of Pan-Slavism and Czech Nationalism, 2012, Academia.edu.

Erin Dusza: Seditious Symbolism in a Skirt. Nationalist Propaganda in the Czech Posters of Alphonse Mucha, Academia.edu.

Joan Tkacs: Alphonse Mucha’s Slav epic and the projection of Czech identity, 2012, University of Georgia.

Marta Filipova: The Construction of National Identity in the Historiography of Czech Art, 2008, University of Glasgow.

Posters, Mucha Foundation.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!