Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

The Ancient of Days, designed, printed, and hand colored by William Blake, was the frontispiece of his 1794 poem Europe a Prophecy. An epic representation of his views on religion, politics, and humanity, this poem is also one of the best examples of his unique artistic style.

William Blake (1757-1827) was the son of a London hosier. Apprenticed to an engraver at the age of 14, he spent time sketching in Westminster Abbey where he gained a love of gothic forms. He joined the Royal Academy in 1779 but had little sympathy with the style taught there. He considered it incomplete and too generalized, and went so far as to describe Academy founder, Joshua Reynolds, as “hired by Satan for the depression of art.” Blake’s preference was for Raphael’s precise Renaissance draughtsmanship and the ideal classical form portrayed in Michelangelo‘s work.

Blake married Catherine Boucher in 1782. He trained her as an engraver and taught her to read and write, and after he opened a print shop in 1784, she became his invaluable assistant. By this time, Blake was part of a radical circle that included artist Henry Fuseli, American revolutionary Tom Paine, feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, and the poet William Wordsworth. Throughout his life, Blake was critical of contemporary society and politics. He supported the American and French Revolutions, and was, at one point, arrested for sedition.

Although he wrote poetry and produced artworks throughout his life, Blake’s work was not widely appreciated. He struggled to make a living as a commercial printmaker. Even with the support of patrons like the artist John Linnell, he died in poverty, virtually unknown.

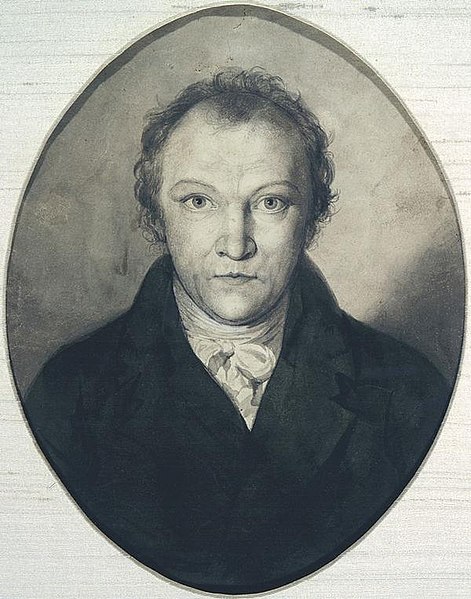

William Blake, Self Portrait, 1802, pencil. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Blake was working at the end of the 18th century, a period which had been dominated by the ideas of Enlightenment. There was a belief in man’s rationality and society’s ability to progress. Technological and industrial development and colonial expansion had created optimism and a desire for reform. For radicals in Europe, the success of America in gaining independence and a new constitution was proof that positive change could succeed.

However, by the 1790s, the French Revolution had descended into a bloodbath and the British government, fearful of unrest at home, was becoming increasingly repressive. Equally, campaigners for women’s rights and the abolition of slavery proved how hollow cries of liberty and equality really were. Many writers and artists were becoming disillusioned. Some retreated into nature, some turned to religion, some inwards to their imagination – and Romanticism was born. Blake, too, hoped for a more innocent world in which spirituality and the imagination were given free rein.

William Blake, The Ancient of Days, from Europe a Prophecy, 1794, watercolor etching, The British Museum, London, UK. Museum’s website.

Blake’s The Ancient of Days was the frontispiece of Blake’s book Europe a Prophecy, published in 1794, which described Christianity as a repressive force on society and criticized what was happening in France. The Ancient of Days was one of 17 colored relief etchings with extra watercolor applied by hand. Every one of the nine surviving versions is therefore slightly different. The Ancient of Days was also said to be one of Blake’s favorite images: he was painting a copy in the days before his death.

The image shows a bearded, white-haired man, kneeling in a red circle, surrounded by fiery light and clouds. He is reaching down into darkness, a pair of measuring compasses in his hand. The title comes from one of the names given to God in the Old Testament, but this is no straightforward image of the Creation or of a Christian God. This is Urizen, a God-like but flawed figure from Blake’s own complex philosophy.

For Blake, Urizen was associated with reason and law: he created the universe but then ensnared it with laws that restrict the imagination. Here, Urizen is shown as a heroic figure, with the body of a classical god, his hair blowing dramatically to the side. Blake’s enthusiasm for Michelangelo is visible in the strong musculature and the dramatically foreshortened pose. But elsewhere, Urizen is represented as old and tired, poring over books or holding a net to enslave men with rational laws.

Even this positive representation of Urizen is ambiguous. The compass seems to grow out of his fingers as if he is losing his humanity. The figure’s pose is awkward, almost painful and introverted. The perfect circle that he sits in is incomplete. A chunk is removed to show that Urizen himself is incomplete without imagination. Imagination is also represented by rich, layered colors. And the figure has turned his back on the warmth and dynamism of the colors and is focused on darkness, tilting so far forward that he almost looks as if he could fall into it.

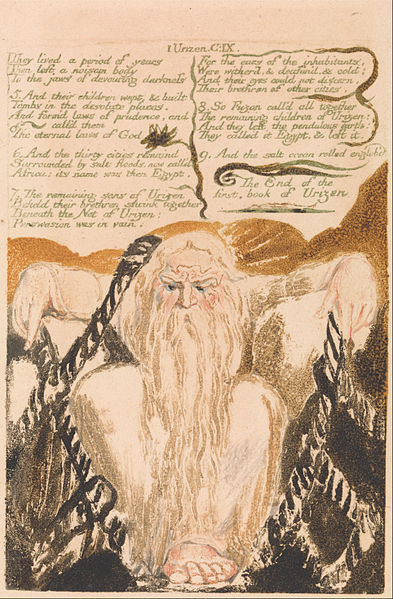

Here, Urizen is shown as old and wizened, clutching the net of reason with which he ensnares mankind. The image also shows how Blake integrated images with his poetry.

William Blake, The First Book of Urizen, 1794, hand-colored relief print, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Blake published his first collection of poems Poetical Sketches in 1783. He continued to write and illustrate books of poetry throughout his life, perhaps most famously his Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794) which contain some of his best-known poems and juxtapose images of childhood innocence and nature with exploitation and poverty in urban life. He also produced works like The Book of Urizen (1794) which in verse form explained his own version of Christianity, as he claimed had been revealed to him in visions.

Blake took total control of his own production process. He developed a unique printing technique that allowed him to combine words and pictures on the page. By writing and drawing on copper plates with acid-repelling ink, Blake created a relief image. The plate was then dipped in acid to create what was essentially the opposite of a traditional engraving. Illuminated printing, as he called it, harked back to medieval manuscripts. It allowed him to illustrate what appeared to be “handwritten” verses, in a style that seemed more like it had been drawn and painted than printed. Many were then also hand-colored to increase their uniqueness.

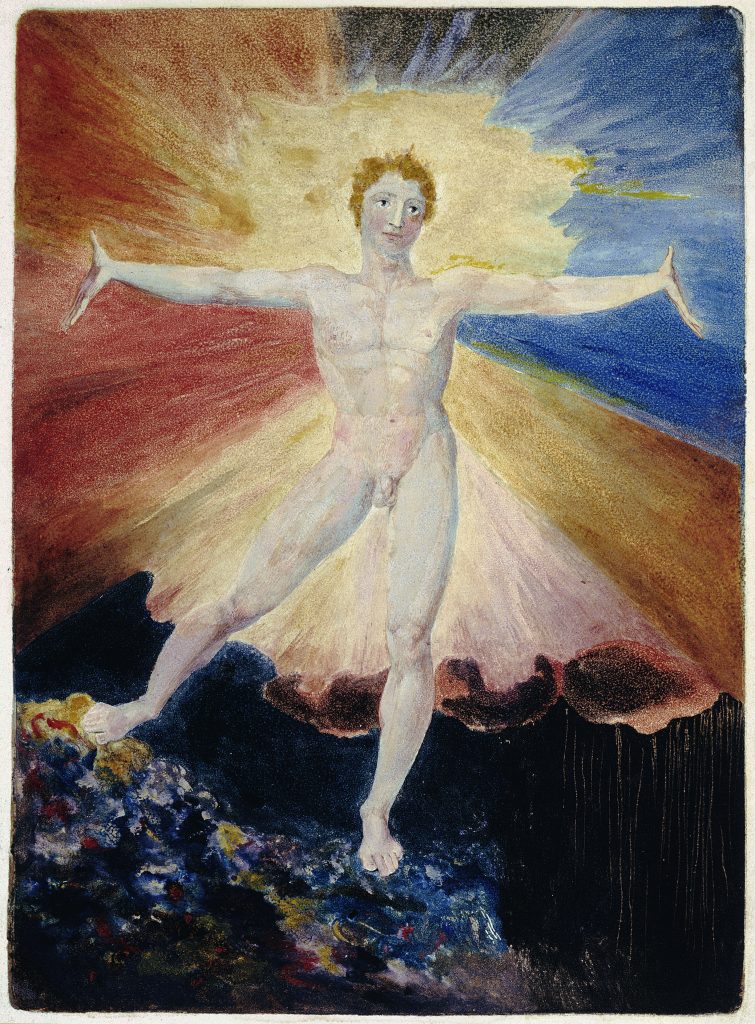

William Blake, Albion Rose or Glad Day, 1793, color engraving with hand coloring, British Museum, London, UK. Museum’s website.

Albion Rose shows a young man against a similar cloud-burst of color. For Blake, Albion is an Adam-like figure, representing mankind before the Fall. There are also similarities with Christ, but like Urizen, he is not just a biblical figure. If Urizen represents reason, the Albion is imagination. Just like in The Ancient of Days, Albion has an idealized, classical body, but unlike Urizen, he is young and outward reaching, as if he wants to embrace the world.

Blake depicted both youth and children in his poetry to show natural innocence and imagination untainted by reason, and the burst of color here represents that joyous emotional and spiritual release. Albion Rose is the opposite of The Ancient of Days: young, open-hearted, optimistic, and joyful. The figure of the man is also firmly grounded, standing on the earth rather than suspended in space and geometry, so there is a sense that he is more human than divine. He is something mankind can aspire to. Albion was also a traditional name for Britain, so like The Ancient of Days, this image has a political message. It expressed Blake’s hope that the country could become a better place.

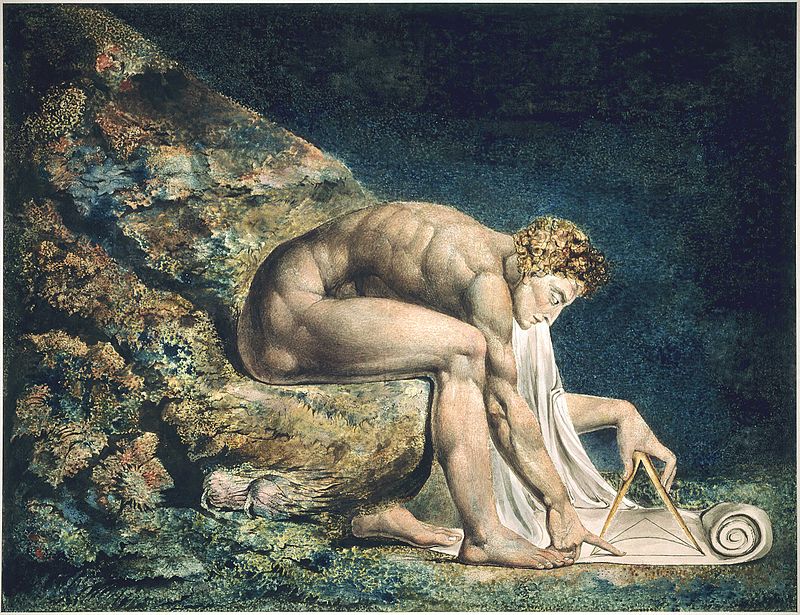

William Blake, Newton, 1804, colored print and watercolor, Tate Britain, London, UK. Museum’s website.

William Blake’s Newton (1804) depicts the famous scientist and discoverer of gravity. Although images of Newton usually represent him as an older man, Blake shows him as a youth, with the body of a Greek god. Newton also holds a measuring compass, and like Urizen, bends forward awkwardly with all his attention focused on the mathematical instrument. The scroll that he is looking at seems to flow from his body as if he is too becoming part of his mathematical calculations. Equally, the scroll looks like a piece of drapery, as if Newton is clothing himself in reason, trying to cover up his naked innocence with it. He is depicted at the bottom of the sea, sitting on a rock, apparently oblivious of where he is, just as Urizen seems to be tipping forward into the darkness. Blake seems to be saying that rational beings can still behave foolishly; here is a man drowning in reason.

William Blake was a one-off. He was a complex man: a poet and a painter, a mystic who had visions throughout his life, a philosopher who created his own complex belief structure, and a political radical who campaigned for social change. But above all, he could create simple, effective images in words and pictures. Blake’s The Ancient of Days is just that. With bold colors and expressive treatment of the human form, he gave a small image huge impact.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!