5 Facts about the Counter-Reformation in Art You Need to Know

The Counter-Reformation was the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation spreading through Europe during the Renaissance.

Anna Ingram 5 December 2024

7 October 2024 min Read

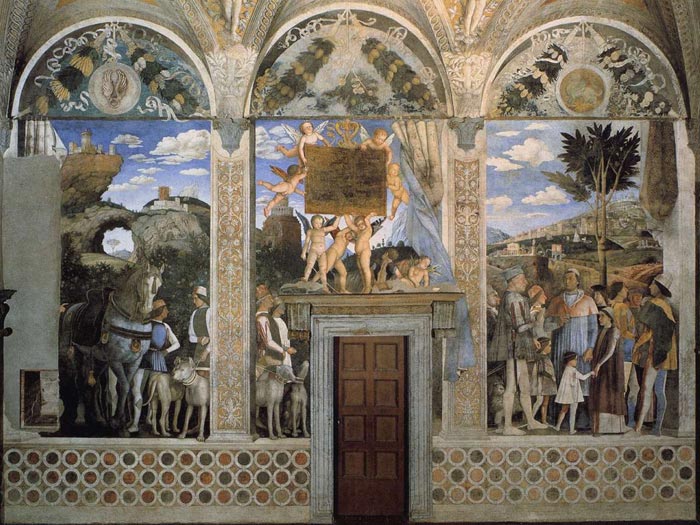

A masterpiece of the early Italian Renaissance, Andrea Mantegna’s Bridal Chamber has been described as the most beautiful room in the world. With his meticulous attention to detail and his pioneering use of spatial illusion, Mantegna delivered the ultimate homage to his patrons, the 15th-century Court of Gonzaga.

Nestled between three lakes, the historic city of Mantua is one of Italy’s most important artistic treasures. A World Heritage site since 2008, Mantua was a leading artistic center during the Renaissance. This was due in large part to the powerful ruling Gonzaga family.

Skyline. Mantua, Italy. European Waterways.

In 1456, the Duke of Mantua, Ludovico Gonzaga, appointed Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506) as court painter. Born in Isola di Carturo, Italy, Mantegna was one of the most respected artists of the Italian Renaissance. Known for his visual experiments, he paid rigorous attention to detail. He also played with foreshortening and perspective, applying subtle shifts in vantage points to fool the eye.

Perhaps his most important commission was the fresco cycle for the Bridal Chamber (Camera degli Sposi) within the imposing Ducal Palace, the royal residence of the Gonzaga family. A Renaissance masterpiece, the room was entirely painted by Mantegna, who depicted his patrons in contemporary narrative scenes.

Andrea Mantegna, Bridal Chamber, view of northern and western walls, 1465-1474, Ducal Palace, Mantua, Italy. Arte Svelata.

While the name of the chamber would suggest it was a bedroom, the room was all but private: it was in fact a reception room and gathering area. The meticulously frescoed walls showcase the opulence of the Gonzaga family. The ceiling is adorned with rich stucco work and the busts of Roman emperors, suggesting a comparison between the Gonzaga family and the Ancient Roman Empire. The room’s arches and other architectural elements, while highly realistic, were all painted by Mantegna in a virtuosic play of optical illusion.

Andrea Mantegna, The Bridal Chamber, 1465-1474, Ducal Palace, Mantua, Italy. Web Gallery of Art. Detail.

On the western wall, through painted curtains, we witness an encounter between Ludovico and his son, Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga. The sculptural, almost statuesque quality of Mantegna’s figures reflects his fascination with the art of classical antiquity. Indeed, humanism and its rediscovery of ancient Roman ideals were in full swing during Mantegna’s tenure as a court painter. In this scene, clusters of children surround the adults, alluding to the dynasty’s line of succession. A saddled horse is being led by its groom meanwhile another courtier detains his dogs—one even has his bottom sticking right out at the viewer. Flanking the left side of the door is another pair of leashed hunting dogs with their owners. One man holds a sealed letter.

Andrea Mantegna, The Bridal Chamber, western wall, 1465-1474, Ducal Palace, Mantua, Italy. Traveling in Tuscany. Detail.

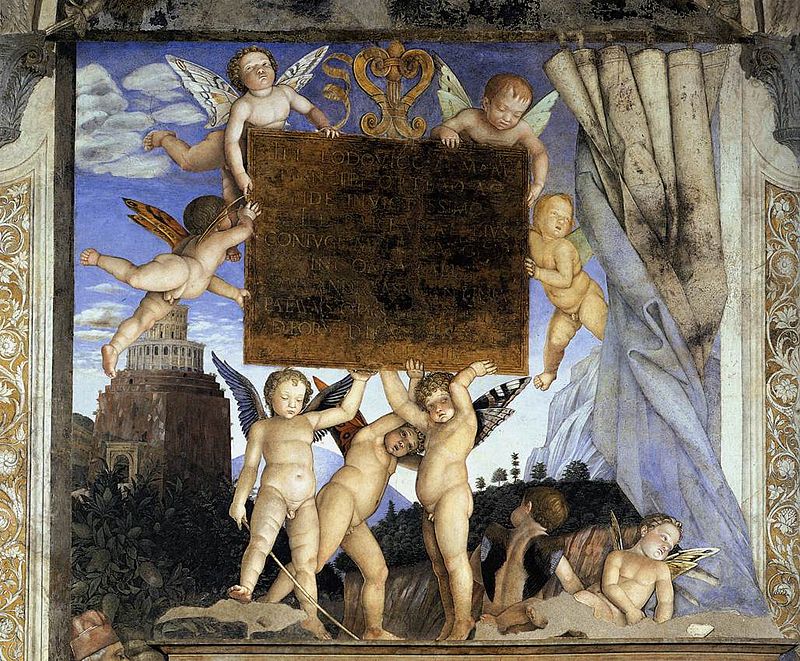

Three winged angels stand atop the cornice above the door and hold the artist’s dedication:

For the illustrious Ludovico, second Marchese of Mantua, best of princes and most unvanquished in faith, and for his illustrious wife Barbara, incomparable glory of womanhood, his Andrea Mantegna of Padua completed this slight work in the year 1474 CE.

The artist’s dedication to Ludovico Gonzaga.

Andrea Mantegna, The Bridal Chamber, 1465-1474, Ducal Palace, Mantua, Italy. Arte Svelata. Detail.

Occupying the north wall is a stately scene of the court of the Gonzaga family. The fresco gives the impression of extended space as the room opens to an exterior garden. Here, too, painted curtains are drawn back leading us into the action. Duke Ludovico and his wife Barbara are surrounded by their family and other members of the court. All figures are regally dressed and form a sea of vibrant red caps. They engage in conversation in a mélange of turning heads and contorted poses. The family’s pet dog peers out at us from beneath the duke’s chair. Mantegna skillfully incorporates the scene into its surroundings by painting a flight of stairs leading up to the elaborately carved mantle of the room’s fireplace.

Andrea Mantegna, The Bridal Chamber, northern wall, 1465-1474, Ducal Palace, Mantua, Italy. Arte Svelata. Detail.

In the far-left corner, a creased letter is being passed into the scene—look familiar?

Andrea Mantegna, The Bridal Chamber, northern wall, 1465-1474, Ducal Palace, Mantua, Italy. Arte Svelata. Detail.

Mantegna’s most celebrated trompe l’oeil is located at the center of the room’s ceiling. A fictive oculus opens up to a blue sky and clouds, surrounded by a lush garland of lemons, ribbons, and greenery.

A charming group of plump putti (cherubs) play around a balustrade. Dramatically foreshortened, they look down on us in what is thought to be the first successful example of the di sotto in sù (from below, upward) method. The mischievous glances of female faces are suspended above us as well as a potted plant perched on a wooden rod— one wrong move and it could fall and strike us.

Andrea Mantegna, Oculus of the Bridal Chamber, 1465- 1474, Ducal Palace, Mantua, Italy. Web Gallery of Art. Detail.

Andrea Mantegna’s frescoes for the Ducal Palace offer a glimpse of 15th-century court life. His illusionistic painting and perspectival experimentations paved the way for 16th-century wall and ceiling painting. Mantegna was also an innovator of the quattrocento and would go on to influence artists such as Pinturicchio, Raphael, and Michelangelo. Masterful and captivating, his frescoes for the Bridal Chamber are just as remarkable today as they were when they were first created for the ruling Gonzaga family.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!