Suzanne Valadon in 5 Paintings

To truly understand Suzanne Valadon, we must look at her art. Let’s explore five of her most compelling paintings, each a testament to how her...

Nikolina Konjevod 30 December 2024

As the 19th century barreled towards the 20th, a profound reevaluation of established gender roles manifested in the confluence of burgeoning modernization and the demands of women for their rights. Both women and men began openly blurring the boundaries of masculinity and femininity by expressing what was viewed as androgynous styles and behaviors. Whilst this sparked irreconcilable outrage in some and signified freedom for others, it permeated artistic culture in such a manner that acknowledged developments in attitudes towards gender ideals whilst maintaining a deeply misogynistic perspective.

The “New Woman,” a term coined by Sarah Grand in 1894, became a buzzword for women who adopted traditionally masculine traits such as ambition, independence, and virility. The “dandy,” on the other hand, was viewed as a feminized man, embodying lofty intellectualism and the elevation of aesthetics, passion, elegance, and leisure. Disturbances to traditional gender dynamics, interwoven in a tapestry of revised religion, mythologies, and philosophy, provided a vehicle for artists to either challenge or reinforce binary archetypes.

O LOVE! what shall be said of thee?

The son of grief begot by joy?

Being sightless, wilt thou see?

Being sexless, wilt thou be

Maiden or boy?Fragoletta, c.1866

Androgyny and Misogyny in Symbolist Art: Edward Burne-Jones, The Depths of the Sea, 1887, Harvard Arts Museums, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Algernon Charles Swinburne was a British poet and art critic associated with the Pre-Raphaelites and Decadence. His poetry collection Poems and Ballads, first published in 1866, is illustrative of how alternative and fluid expressions of gender and sexuality often maintained a reinforcement of the subjugation of women. He dedicated the body of work to Burne-Jones, who frequently depicted the sexual threat of masculinized women.

The Depths of the Sea, for example, depicts a muscular siren with a phallic tail dragging a sailor to his death, demonstrating the fatal consequences of female virility. Swinburne’s poetry received criticism for his erotic same-sex descriptions and blending of masculine and feminine bodies which challenged sexual conventions and the line between obscenity and art. Although Swinburne challenged socially constructed boundaries, scholars have argued that the binaries were deconstructed only to be reconstructed in a reformulation of male hegemony.

Whilst the New Woman and the dandy were often lumped together in the media as of similarly perverting nature, masculinized women in visual art were often portrayed as dangerous, whereas feminized men reflected ultimate beauty. This was according to the mythic ideal of the wholeness of androgynous men as representative of the spiritual perfection of the male body.

Jean Delville reflects the spiritualized ideal of androgyny. A Christ-like depiction of Plato is surrounded by highly feminized male figures in a dreamlike utopia resembling an Edenic scene. As a theosophist-spiritualist, Delville imbued multivalent symbolism, reflecting theosophy’s syncretic approach to religion, spirituality, and philosophy. As with Swinburne’s poetry, the painting blurs the line between purity and sensuality. Delville commented on his work that “beauty sheds its lights, quivering with the divine radiance, the wondrous effect of the mystic harmony,” encapsulating the divine perfection of the androgynous male, yet expressing distinctively sexualized undertones.

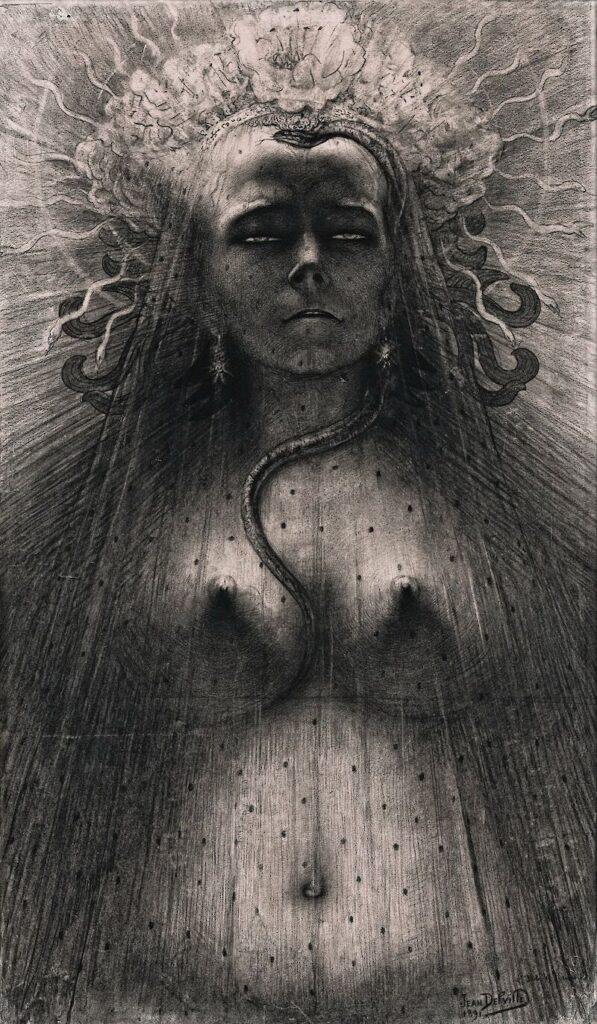

In comparison to the glorified male bathed in ethereal hues, Delville’s greyscale drawing, The Idol of Perversity, depicts a demonized and hyper-sexualized Medusa bestowing a direct deathly glare. The female figure’s serpentine hair forms a deceptive halo, with one slithering snake connecting her mind to her erect breasts, symbolizing the threat and obscenity of emboldened female sexuality.

Androgyny and Misogyny in Symbolist Art: Jean Delville, The Idol of Perversity, 1891, Galleria del Levante, Munich, Germany.

Delville and Burne-Jones, amongst many Symbolist artists, demonstrated an interest in the revival of mysticism, Hellenic hermeticism, spiritualism, and the occult, amongst a myriad of manifestations of alternative spirituality that emerged in late nineteenth-century Europe. Various societies and organizations centering on esoteric ideas and ancient philosophies surfaced, drawing on gnostic practices as a foundation on which to achieve spiritual transcendence and psychic powers. Of these societies, the Order of the Rose Croix was distinctive in its aim of informing the moral value of art. Based on the occult teachings of the Rosicrucian Order that originated in the 17th century, the Order of the Rose Croix emphasized spiritual and social reformation. Its founder, Joséphin Péladan, who purposefully feminized his name, spearheaded a series of exhibitions known as the Salon de la Rose+Croix between 1892 and 1897.

Prominent Symbolists from across Europe participated, including Delville, Fernand Khnopff, Carlos Schwabe, and Gustave Moreau. Burne-Jones had also received an invitation to participate but declined. Péladan and his cohort of mystical Symbolists rejected the trend towards the secularization of art, manifesting in movements such as Realism and Post-Impressionism, and instead aspired to showcase art that was perceived to encourage morality in what was thought to be a degenerating society. The rejection of the material world in favor of “the Idea” as the subject matter was one of the distinguishing features of Symbolism, and hence, the movement aligned succinctly with Péladan’s vision of transcendence and the renunciation of secular materialism. He believed that art reflected a society’s spirit and, accordingly, curated a visual culture that bolstered values of tradition, hierarchy, idealism, and the metaphysical quest for spiritual truths. Esotericism was the ideal vehicle for melding science, evolutionary theory, and spirituality to renew spiritual ambition in the wake of declining religious fervor.

It was important for Péladan to progress the Decadent artistic culture away from an emphasis on indulgence in the flesh and carnal pursuits and towards didactic moralism. Therefore, a significant aspect of the imagery collated was the representation of both idealized and degraded female archetypes, seen to either uphold chastity or translate the horrors of sexual perversity through their masculinization.

In many artworks selected, women were depicted as sexually passive and subservient to men, reflecting deep-rooted fears of women’s increasing demands for individuality, rights, and liberation. In response to this, Péladan, and many of the artists associated with him, promoted the common idea that the suppression of women’s individualism was fundamental to combatting the horrors of sexual degeneration and the disintegration of traditional social, religious, and moral structures. Simultaneously, physical beauty was regarded as reflecting spiritual purity, positioning women in a paradox of embodying both attractiveness and asexuality; purity without sacrificing desirability. This convoluted ideal of women as passively available yet void of desire, a femme fragile, juxtaposed the categorization of women as a femme fatale, who actively threatened the moral fiber of men and the decency of society.

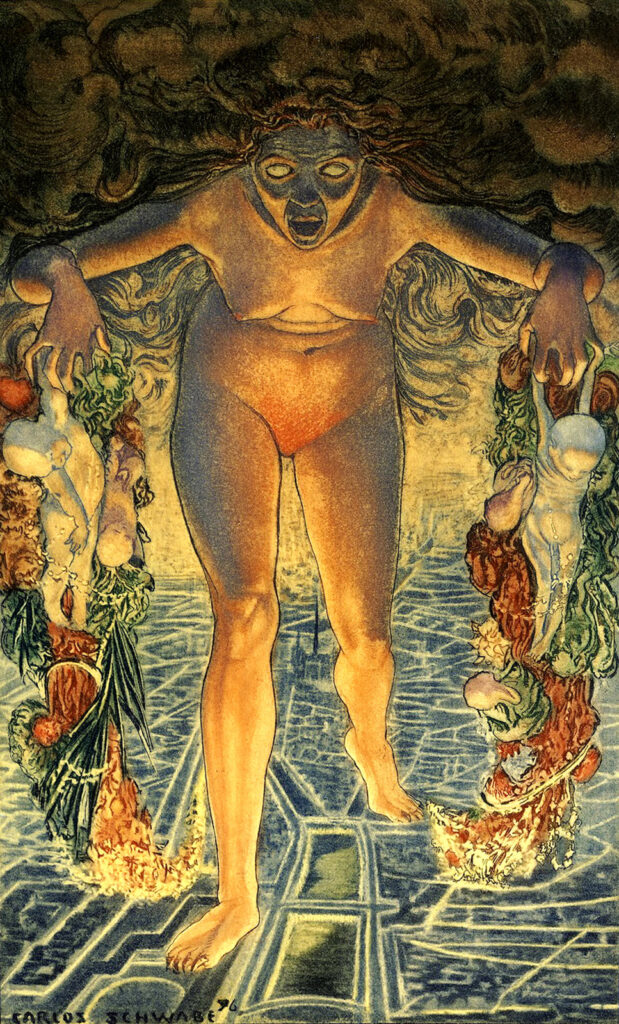

Androgyny and Misogyny in Symbolist Art: Carlos Schwabe, Crepuscule, 1900, illustration to Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal.

The use of sexualized female imagery to suggest lust, death, and destruction in contrast to ideal womanhood was used to great effect by prominent Symbolist artists across Europe. Notably, Schwabe prolifically depicted monstrous, deviant, masculinized, and infanticidal women, such as the above illustration of a gargantuan woman looming over the city wielding dead babies. This archetype contrasted the well-established depiction of ideal womanhood as encompassing virginity and purity through to motherhood and servitude that depended on the universalization of women’s historical representation and experience. The extension of traditional archetypes aimed to portray a juxtaposed view of women that explicitly evoked evil, destruction, and sexual perversity. Although reflective of medieval iconography, religious mythologies, and esotericism, the contemporary shift in ideas surrounding gender formed a visual and artistic culture that was distinctively rooted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The androgyne is the virginal adolescent male, still somewhat feminine, while the gynander can only be the woman who strives for male characteristics, the sexual usurper.

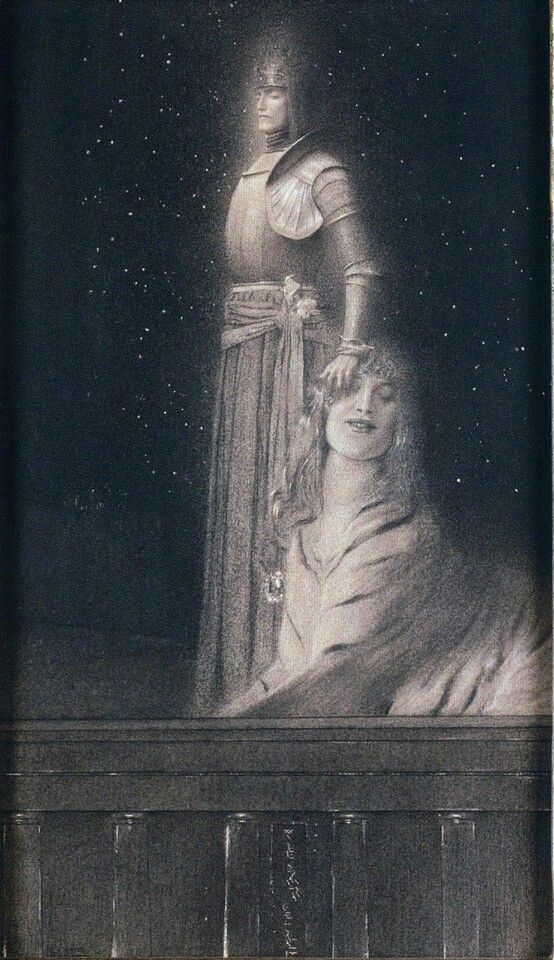

For Péladan and those associated with him, the androgyne was viewed as the ideal form according to the hermetic principle of the unified male and female from which Adam and Eve were split. In this iteration of the creation myth, corporeality, the soul, and the immortal spirit could not be divided equally between the male and female forms, and therefore, man inherited the spirit and the mind and woman inherited the body and earthly, baser, qualities. In this regard, women were closer to beasts, as illustrated by Khnopff in his depiction of the divine androgynous male holding his hand over a beastly woman.

The principle of the divine hermaphrodite and subsequent separation of genders echoed throughout fin de siècle art, leading to the depiction of androgyny as indicative of spiritual wholeness for male bodies, and degeneracy for female bodies. Whilst seemingly reflected in society as progressive and radical, its translation through art and literature often upheld the misogynist standards of the period.

Androgyny and Misogyny in Symbolist Art: Fernand Khnopff, The Meeting of Animalism and an Angel, 1889. Pinterest.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!