5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Love him or hate him, Warhol’s art is notable for his use of mass production and pop culture. As Christopher Makos said in a 2011 interview with the BBC, “The bottom line is that almost anybody knows the name Andy Warhol”. It can be argued that his whole life was one giant and continuous collaboration with the world. At least, that’s what the Netflix docu-series on The Andy Warhol Diaries, elaborates on in its 6-episode arc.

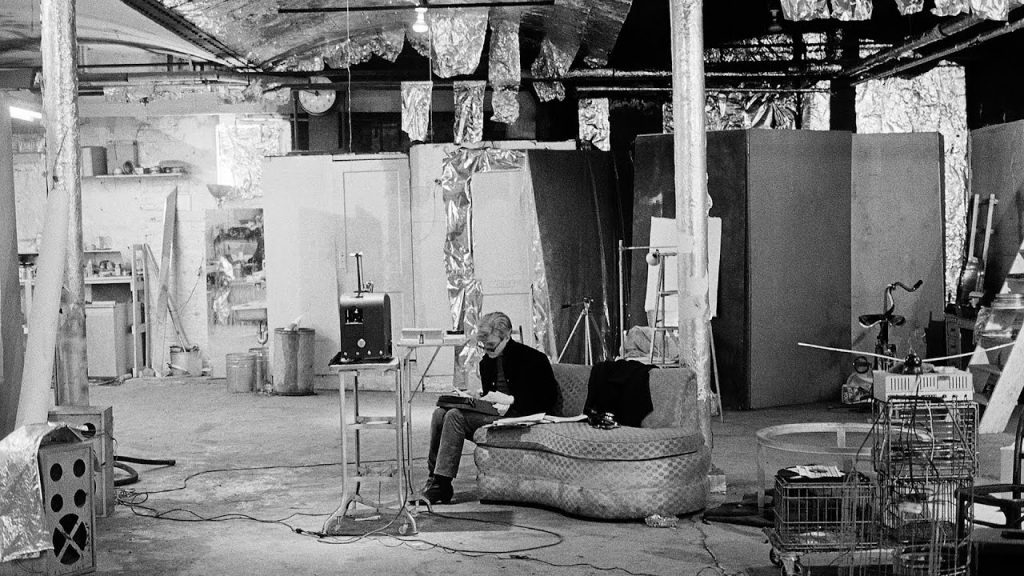

Warhol’s Factory started in the early 1960s was not only a place for the artist to personally create. It became a place for parties and gatherings over its life. Even though it moved a handful of times, the intention of the space remained the same. The Factory was a space where Warhol created, like-minded individuals mingled, and history was made.

It has been said of Warhol and The Factory that it thrived for as long as it did because he and his space gave others the opportunity to be unapologetically themselves. They could be exactly who they wanted to be, outside of society’s standards. Within the walls of Warhol’s home and work, nothing seemed to be too taboo for either discussion or creation. Warhol let others shine and by doing so he was able to shine too. In this collaboration of sorts, he thrived on others’ creativity and the openness of their desires.

Still from Andy Warhol’s Silver Factory, Design Museum Gent, Ghent, Belgium. YouTube.

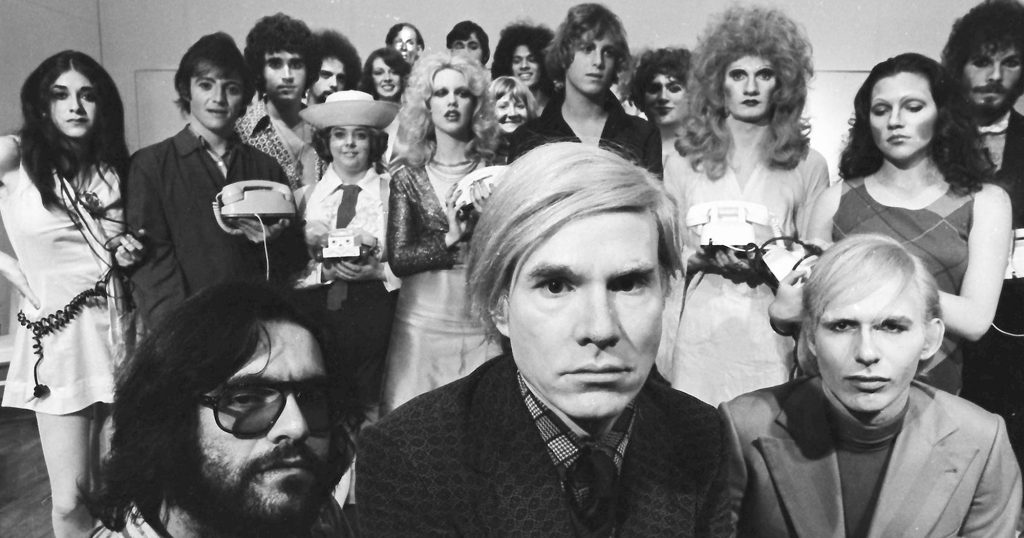

Jack Mitchell, Warhol’s Superstars. Refinery29.

Though these superstars, as they are known, either acted in Warhol-made films, worked for him at Interview Magazine, or were members of his entourage, the relationships were symbiotic. It seemed that if you spent time around the Warhol, your star was bound to rise, even if only for 15 minutes.

A writer for Smithsonian Magazine argues that while incredibly true of today’s culture, the notion of everyone being famous for at least 15 minutes, might not have necessarily derived from Warhol’s lips, exactly. But just like he was known to brand himself and his art, society has latched onto the notion that he did in fact say this.

Artists of the 1980s, such as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat found fame of their own even before officially meeting Warhol. However, their stardom certainly did not falter upon meeting the artist. His star shone brightly on them, as it had with his superstars in the 1960s and 1970s. Likewise, Andy Warhol appeared hipper with the help of these artists recognizing him, in turn.

With Warhol by their side, or in their artistic circle, these artists took their art to new levels. The argument can be made that he elevated their art. However, like calls to like and therefore Warhol’s essence beckoned to the great artists of his time.

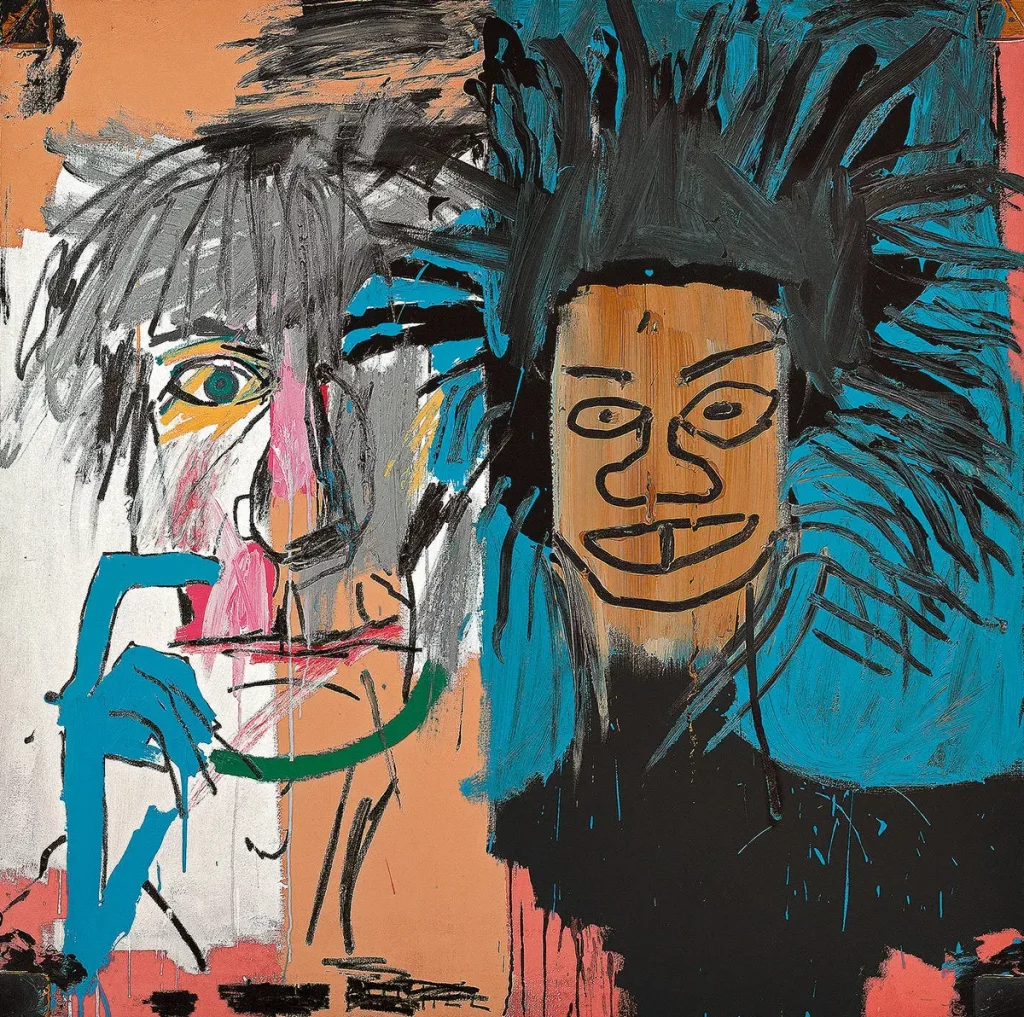

Basquiat was an up-and-coming artist from Brooklyn when he met Warhol. Although, as Warhol tells it, he’d passed Basquiat selling t-shirts on the street before, giving him a little bit of money here and there. Though the way in which they met is the subject of debate, it is a fact that in time the pair formed an unlikely friendship. With Basquiat’s awe of the older artist, and Warhol’s love of the “new,” big things were meant to happen. Upon their first meeting, Basquiat hurried to his studio and painted a portrait of himself and of Warhol on one canvas. Done in Basquiat’s striking style, the canvas was still wet when he delivered it back to Warhol.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Dos Cabezas, 1982, Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York, NY, USA. Revolver Warhol Gallery.

Makos met Warhol after the infamous 1968 shooting where one of Warhol’s previously employed actresses shot him at The Factory. The images below, from an early 1980s collaborative photographic series with Warhol, were meant to display how the idea of beauty could be construed, and how others could view you. In the photographs, Warhol changes wigs, makeup, and even wardrobe to toy with his identity.

Christopher Makos, Photographs of Andy Warhol from the Altered Image series, 1981, New York, NY, USA. Interview Magazine.

He didn’t want to look like a beautiful woman, He wanted to show the way it felt to be Beautiful…

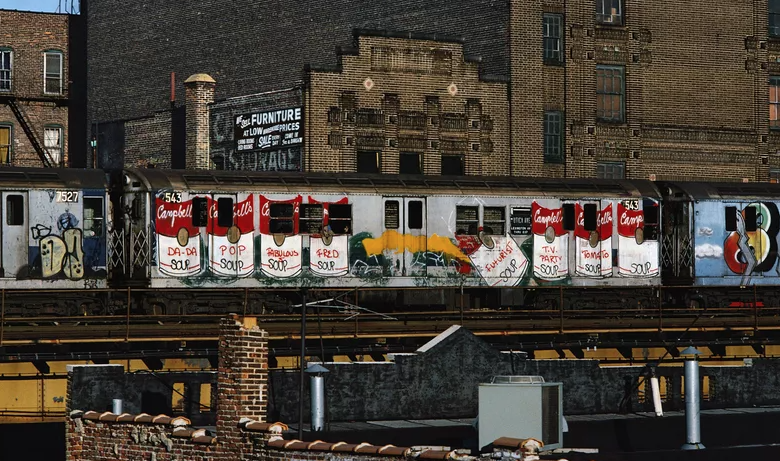

The Netflix docu-series The Andy Warhol Diaries details the effect of Andy Warhol’s prior art on these other artists. It specifically mentions Fab 5 Freddy, who, together with other artists, recreated their own versions of the famous Campbell’s Soup Cans onto the side of a city train in their graffiti styles. However, taking this specific example for instance, collaborations did not and do not always take the same shape or form: like Fab 5 Freddy’s take on Warhol’s soup cans. He was clearly influenced by the artist’s pop art style even if Warhol himself didn’t take it to the streets with cans of spray paint to create this piece.

Martha Cooper, Photograph of Campbell’s Soup by Fab 5 Freddy, 1981, Steven Kasher Gallery, New York, NY, USA. Artsy.

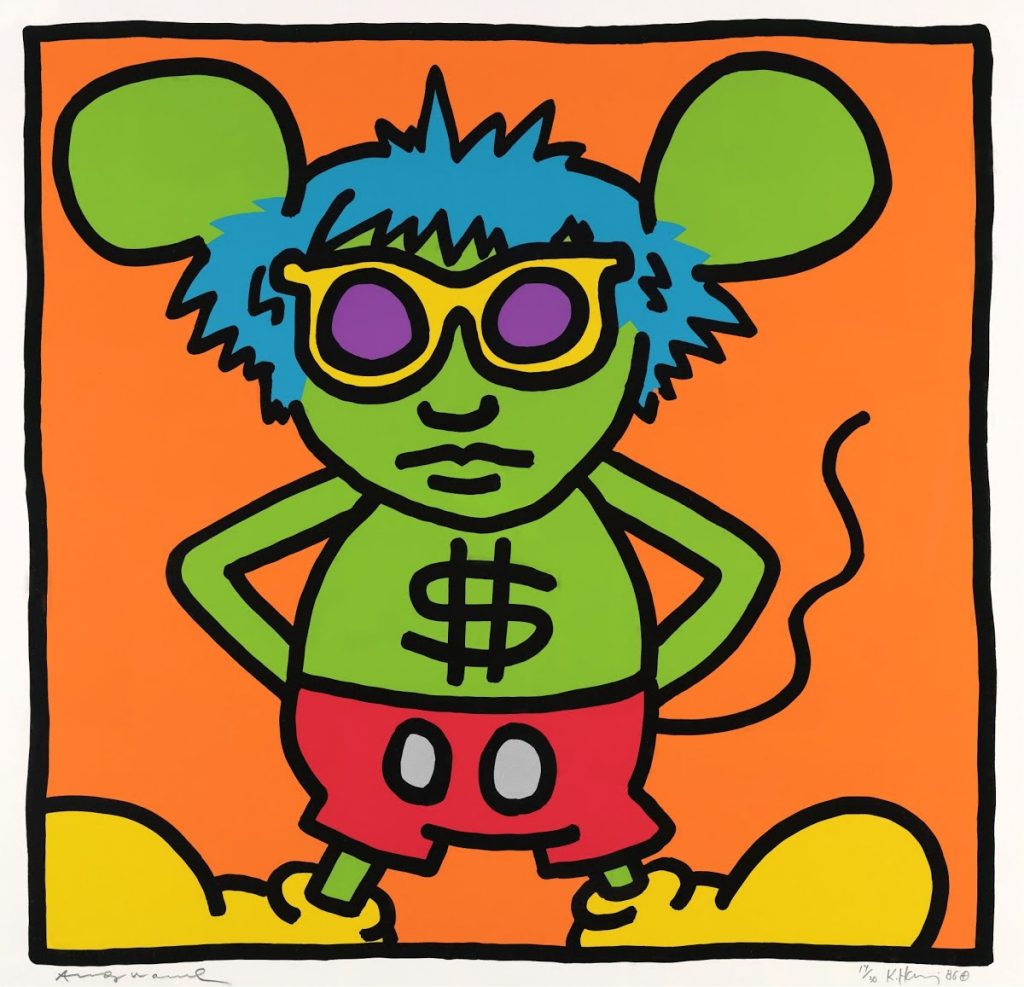

As seen below in one of Haring’s Andy Mouse paintings, there is an obvious influence from Warhol. In his eyes, Haring had these two great things side by side. His love of Disney and Mickey Mouse and his love for the Pop artist.

Keith Haring, Andy Mouse, 1986, Nakamura Keith Haring Collection, Yamanashi, Japan. Google Arts & Culture.

Past the above-mentioned collaborations, Warhol used assistants within his own studio. These assistants would make the screen prints that he is famously known for, and much more.

It’s not unusual for big artists to have assistants. Going back even to the Renaissance, artists trained in or held schools where their assistants took part in helping to paint parts of their biggest masterpieces. Did these artists know that they were always to be mere echoes in the background of those who have gone on to be much larger in the realm of art?

With his famous print-screen portraits, Warhol was bringing in roughly $25, give or take. Those same paintings sell for millions of dollars today. While artists like Warhol, in his unashamed use of studio assistants, make light of the use of them to mass produce art, it brings to the forefront the question of whether or not these assistants were being paid properly, if at all. In a 2020 Vice article, the author Eda Yu begs an important question:

At its core, the art world has long relied on a foundation of workers who make a fraction of what these high-end artists make from selling a single piece. And when artists like Koons or McGinley have pieces selling in the tens of thousands to millions, it feels pertinent to ask: Does it make sense that a single individual receives the credit even when they don’t—or can’t—make the work themselves? Is it time to reevaluate what it means to be an artist assistant and where ownership of art in collaborative processes begins and ends?

Vice.

Here is one last account from George Condo, a previous assistant of Warhol: “I worked at Warhol’s Factory for nine months and it was incredibly intense. They asked me if I wanted to be on the assembly line; I ended up doing all the diamond dusting. I would go in at 10 AM and finish at midnight — it was slave labor. We had to get things done under extreme pressure and execute it perfectly. On top of that, Andy was never at the Factory. He was in his office on 18th Street, and we were printing on Duane Street in TriBeCa. There was a telephone that sat next to the silkscreen machine and when it would ring, Rupert would pick up, listen, and say something like, “Andy’s on the phone. He wants to change the color from purple to black.” So then we would have to rush to change the entire print and make a whole new group of 300 pieces. And there were only about six or seven studio assistants. We made probably 5,000 prints over the course of the nine months I was there.”

The Diaries of Andy Warhol, directed by Andrew Rossi, 2022, Netflix.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!