How Did Paris Fall in Love with Ballets Russes?

Ballets Russes was a ballet company founded by the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev. No doubt, Ballets Russes made Russian ballet famous all...

Guest Profile 24 May 2023

Anna Pavlovna Pavlova was a Russian prima ballerina of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. She was the main artist of the Imperial Russian Ballet and the Ballets Russes of Sergei Diaghilev. Pavlova was a beautiful and inspiring woman and she was depicted in paintings by many famous artists of her time.

Anna Pavlova (1881–1931) was known around the world for her role in The Dying Swan for which she traveled to many places including South America, India, and Australia. At the age of ten, Pavlova was accepted into the Imperial Ballet School and performed on stage in Marius Petipa’s Un conte de fées (A Fairy Tale).

Pavlova quickly rose to fame and became the favorite of old maestro Petipa. She performed the title role in Paquita, Princess Aspicia in The Pharaoh’s Daughter, Queen Nisia in Le Roi Candaule, and Giselle. She was named danseuse in 1902, première danseuse in 1905, and, finally, a prima ballerina in 1906. Her admirers called themselves the “Pavlovatzi.”

At the Imperial Ballet School, young Pavlova’s early training was difficult. Classical ballet was not easy for her. She had severely arched feet, thin ankles, and long limbs that clashed with her small, compact body. She was often provoked by her fellow students who called her “the broom” and “La petite sauvage.” Pavlova was, however, unaffected by this and focused on her technique. In her own words:

No one can arrive from being talented alone. God gives talent, work transforms talent into genius.

– Anna Pavlova, quote source: “Women in History: Anna Pavlova, The Iconic Ballerina”, 2019, Karbatin.com.

She took extra lessons from notable teachers of the day such as Christian Johansson and Enrico Cecchetti (who was considered the greatest ballet virtuoso of the time and founder of the Cecchetti technique). In 1898, Pavlova entered the “classe de perfection” of Ekaterina Vazem, former prima ballerina of Saint Petersburg’s Imperial Theatres.

During her final year at the Imperial Ballet School, she performed many roles. She graduated in 1899 at the age of 18 with the highest distinction and made her official début at the Mariinsky Theatre in Pavel Gerdt’s Les Dryades prétendues (The False Dryads).

Sir John Lavery (1856–1941) was an Irish painter best known for his portraits and war paintings. Born in North Belfast, Lavery attended the Haldane Academy in Glasgow and the Académie Julian in Paris. When he returned to Glasgow, he was associated with the Glasgow school. In 1888 he was commissioned to paint the state visit of Queen Victoria to the Glasgow International Exhibition. This launched his career as a society painter and he moved to London soon after.

Pavlova danced in London with Sergei Diaghilev’s company for the first time in the summer of 1910. She caused a sensation with her Dance Bacchanal from Petipa’s ballet The Seasons. Lavery was commissioned to sketch Pavlova for the London News. Lavery agreed on the condition that Pavlova would keep her appointments, which she did.

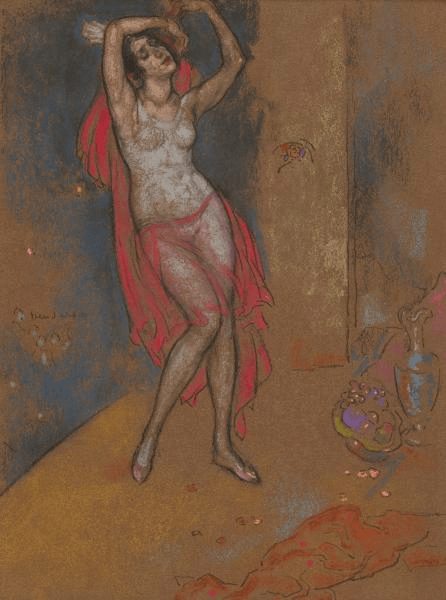

During her three-month stay in London, Pavlova posed for Lavery on a regular basis. As a result, he produced two full-length portraits of Pavlova as a Bacchante. The liveliest version, sometimes known as The Red Scarf, is painted with tremendous freedom in a profusion of artificial pinks, greens, and pale blues that capture the color and energy of the dance.

In Anna Pavlova as Bacchante, Pavlova is portrayed as completely lost in her dance. Her arms are raised over her head and she is holding a diaphanous red scarf. One of her legs is raised while the other barely touches the floor. A critic of The Observer wrote on 16 April 1911:

Mr. Lavery’s portrait of the Russian dancer Anna Pavlova caught in a moment of graceful, weightless movement … Her miraculous, feather-like flight, which seems to defy the law of gravitation.

– Critic, The Observer, 1911, quote source: The Edwardians exhibition, The National Gallery of Australia, 2004.

Pavlova was quite a rule-breaker as she danced unconventionally with her bent knees and bad turnouts.

Dancing was meditative for her; she would often lose herself in her performances to the point of tumbling over and causing accidents. However, she always knew how to turn her flaws into her strengths. Her teacher Pavel Gerdt had once reminded her that her daintiness and fragility were her greatest assets.

Pavlova was well-known for her role as The Dying Swan (1905), a solo ballet performance. She danced to Le cygnet (The Swan) from The Carnival of the Animals by Camille Saint-Saëns. Throughout her career, Pavlova preferred the melodious “musique dansante” of the old maestros such as Cesare Pugni and Ludwig Minkus. Little did she care for Stravinsky’s avant-garde music or anything that was different from the salon-style ballet music of the 19th century.

This half-length portrait, Anna Pavlova as The Swan, relates closely to Lavery’s large picture of Pavlova in the same role. The Swan was a short solo performance created for Pavlova by choreographer Mikhail Fokine. It portrays the last minutes of the dying bird’s life, popularly known as The Dying Swan.

Pavlova is wearing a white tutu with stiffened wings over the skirt. Her face is framed in feathers and a jeweled headdress. On her breast, there is a blue glass jewel. Many dancers who later performed the solo piece wore a red jewel, suggesting that the swan has been shot. However, the original idea was that the swan, at the end of its life, is drifting and drowning in the water.

Pavlova was extremely particular about her costumes. The tarlatan underskirts of her tutu had to be starched to exactly the right degree. Since this fabric was not available in London or Paris it had to be imported from America every year. After every second performance, she renewed the tarlatan skirts of her Swan costume.

Le Mort du Cygne: Anna Pavlova was inspired by Pavlova’s first London season, painted in 1911 and shown at the Royal Academy in 1912. In this second composition, Lavery chose to paint Pavlova as The Dying Swan.

Pavlova left London before the painting was completed so Lavery’s wife, Hazel, modeled for him dressed in Pavlova’s costume. Although Lavery used two head studies of Pavlova as an aides mémoires her husband, Victor Dandré, did not consider La Mort du Cygne a good likeness and much preferred the Bacchante.

In Le Mort du Cygne: Anna Pavlova, Lavery aimed to express the poignant death of a beautiful bird, the swan. The ballerina sinks to the floor, light dancing off her white costume and pink satin shoes. Her figure contrasts with the dark background and the fountain creates a sense of quiet contemplation. The painting stands in contrast to the vivid excitement of the Bacchante.

Pavlova was always partial to the dance of the dying swan. For years she kept swans in the garden of her home in Hempstead, London, so she could study their movements. The inspiration for the swan dance first came to her while watching the swans in a public park in Leningrad.

Valentin Alexandrovich Serov (1865–1911) was a Russian painter and an eminent portrait artist of his era. Raised by musically-inclined parents, Serov was encouraged to pursue art and studied in Paris, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. Serov frequently used various graphic techniques – watercolors, pastels, and lithographs.

Les Sylphides was premiered by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes on June 2, 1909, at Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris. The long white tutu that Pavlova originally danced in was designed by Léon Bakst. It was soon adopted by the entire female corps de ballet. Serov captured Pavlova in a spontaneous moment which was characteristic of his paintings.

Pavlova’s ballet shoes were specially crafted for her extremely arched feet. She strengthened her pointe by adding a piece of hard leather on the soles for support and flattening the box of the shoe. This was considered cheating because a ballerina must hold her weight en pointe, not on her shoes.

Over time this became an acceptable practice in ballet because it was less painful for the performers. However, Pavlova never liked her shoes and asked photographers to remove them from her pictures.

William Penhallow Henderson (1877–1943) was an American painter, architect, and furniture designer. Henderson grew up in Medford, Massachusetts, and Texas. He studied at the Massachusetts Normal Art School and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Henderson took an interest in the Indian and Hispanic residents of Southwest America. In 1916, after more than a decade teaching and painting in Chicago, he moved to Santa Fe with his wife – poet and editor Alice Corbin.

Anna Pavlova in Oriental Fantasy may have been inspired by Pavlova’a annual tours to the United States between 1912 and 1926. It is believed that a generation of dancers turned to ballet because of her. She was responsible for making the Americans ballet-conscious. In Anna Pavlova in Oriental Fantasy, Pavlova has the same diaphanous red cloth as painted by Lavery, only now she is wearing it, instead of her ballerina costume. Her body is barely covered and one can see her pink ballet shoes.

The painting is a fusion of two cultures, Western and Eastern, yet what remains the same is the dance. Pavlova is unaware of the audience’s presence and dancing like no one is watching!

Bruce Turner (1894–1963) was a British painter associated with the Leeds Art Club. Pavlova depicts the noted Russian ballerina who performed three times in Leeds in 1912. The canvas consists of small, heavily impastoed dashes of primary colors (blue, yellow, and red) that radiate fan-wise from various points in the composition. Across this background, the figure moves are broken up, and multiplied to give a sense of the dancer’s movement.

Pavlova’s performance in Leeds was described as “the event of the century,” suggesting the stir her status had caused. Pavlova’s dancing form is depicted in a manner that echoes the Italian futurist paintings in an attempt to capture the energy of the ballerina’s movement.

The dancer was a key motif in Futurist art and Turner’s Pavlova tracks the figure’s movement giving it a sense of passage through space. He may also have been inspired by the stop-action photographs of Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904).

Turner may also have visited the Italian Futurist, Gino Severini’s, exhibition of paintings in Sackville Gallery, London, in 1912. The mosaic-like touches and the crusty paint in Pavlova closely resemble Severini’s The “Pan Pan” Dance at the Monico, 1909–11, suggesting a close study of his paintings. Turner’s Pavlova represents one of the earliest futurist paintings in Britain and is one of the most avant-garde paintings.

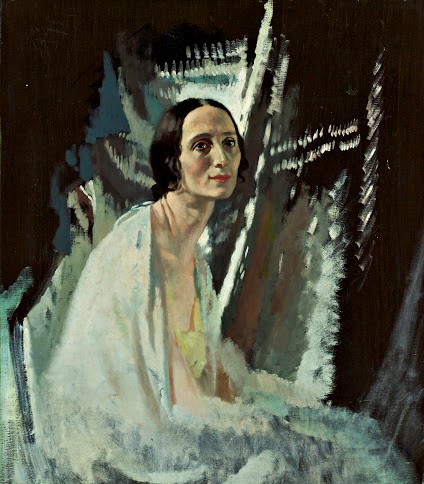

William Orpen (1878 –1931) was an Irish artist who worked mainly in London. He was a successful portraitist of the well-to-do Edwardian society. Like Lavery, he was also a prolific official war artist during World War I. Orpen was known for painting the brutality and aftermath of the war, especially the battlefield strewn with the bodies of dead soldiers.

Orpen probably painted this unfinished portrait of Pavlova when they met during her visit in 1912. He was visiting his ailing mother meanwhile Pavlova was performing in Dublin. They got along quite well in spite of the fact that Pavlova couldn’t speak English.

In Anna Pavlova (Unfinished), we see Pavlova not as a performer but as a person. Since the painting is unfinished it is not clear what Orpen wished to depict, but her pose suggests she was sitting for a friend. It is unclear if she is wearing her ballerina costume.

Although her body is still, her gentle smile and the glimmer in her eyes suggest a certain excitement. She is wearing what appears to be a shawl over her shoulders and her arms are resting on her lap. She is looking through the spectator, focusing her gaze onto something we will never know.

In 1912, Pavlova settled in London. Her house is now the London Jewish Cultural Centre. While traveling from Paris to The Hague on a train, Pavlova became ill and developed pneumonia. She could not be treated and died of pleurisy. Pavlova was laid to rest, dressed in her favorite swan costume, which was her last wish.

Although we know little about her personal life, Pavlova lived a very successful and glamorous public life, built upon her grit and hard work. She dedicated her life to ballet, a dance that became synonymous with her name.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!