Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Anni Albers once referred to textile-making as “rather sissy”. Fortunately she later had a change of heart. From the Bauhaus in Germany to Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Anni Albers revolutionized textile art in the 20th century. Her decades of design innovations—at once functional and beautiful—bridge the gap between traditional craft and fine art.

Photograph of Anni Albers in her study at Black Mountain College, 1937, Asheville, NC, USA. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation via Guggenheim Bilbao.

Anni Albers (1899–1994) was born Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischman into a wealthy Berlin-based family. Despite the limited educational opportunities available to women, Albers was always intent on training as an artist.

As a young adult she applied to study at the Bauhaus, a radical new art school whose mission was to unite art, craft, and technology through modern design. Albers’ first application to the Bauhaus was rejected but she persisted and eventually gained acceptance.

Despite notions of “art for all,” the early Bauhaus maintained the traditional hierarchy of fine art over traditional craft. This hierarchy was also gendered, with painting, sculpture, and architecture reserved for the realm of so-called male genius.

After completing two terms of basic instruction at the Bauhaus it was time for Anni Albers to choose her specialization. “The only thing that was open to me was the weaving workshop,” she later recalled. “And I thought that was rather sissy.”

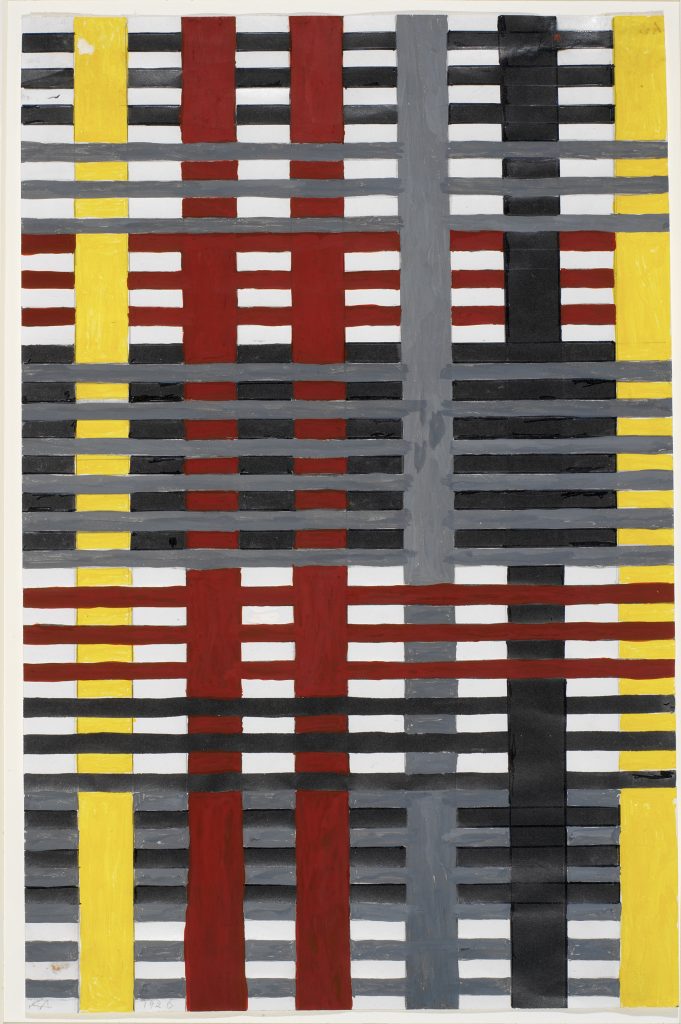

Anni Albers, Study for Unfinished Hanging, gouache with pencil, 1926, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation via Guggenheim Bilbao.

Anni Albers embarked on her education in weaving with reluctance. However she soon found herself pleasantly surprised by the versatility and complexity of the medium. Believing that textile art had the unique power to be both beautiful and useful, Albers set out to investigate every aesthetic and function possibility. For example, she loved that a well-designed textile could serve as an effective blackout curtain and at the same time, look at home in a modern art gallery.

At the Bauhaus Albers learned to experiment with various materials and techniques. She also dared to turn the textile tradition on its head. Mainstream European textiles were usually narrative or figurative and they were produced by craftspeople who copied an existing design by someone else.

Instead Albers composed her own abstract works directly on her loom, thereby unifying the design and production processes as per the Bauhaus mission. She created abstract designs that purposefully highlighted, rather than disguised or overshadowed, the intrinsic elements of her chosen fibers.

It was also at the Bauhaus that Anni met and married Josef Albers, a student in the glass workshop and an emerging abstract artist. The Bauhaus named Albers head of the weaving workshop in 1931, but by 1933 she and Josef had fled to the United States to escape the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany. Josef and Anni Albers both began teaching at Black Mountain College, a progressive art school in North Carolina. The couple dedicated the rest of their lives to their art and to each other.

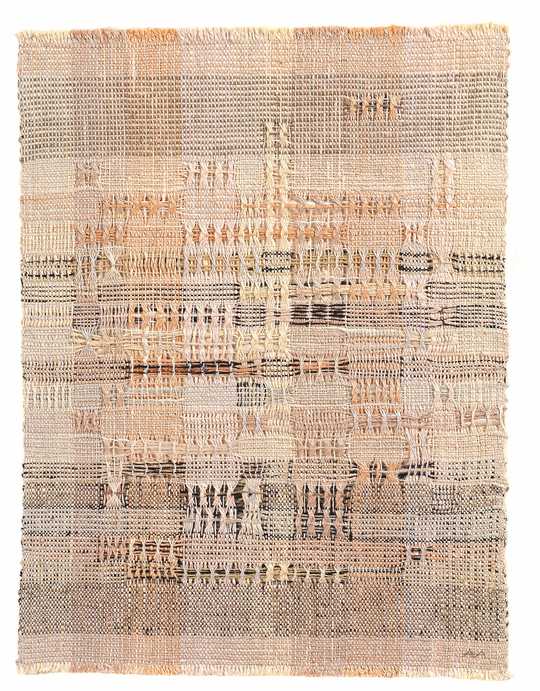

Anni Albers, Development in Rose, linen, 1952, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation via Tate.

Living in the United States gave Anni Albers greater proximity to her “greatest teachers”, the ancient weavers of Mexico and Peru. As she continued to cultivate her art practice, Albers also visited Latin America and collected pre-Columbian art and textiles.

The vibrant textile traditions Albers discovered during these frequent travels inspired her. She was especially fascinated by textiles crafted in cultures that didn’t have a written language. Instead of a familiar alphabet, a series of seemingly abstract threads and knots facilitated an equally complex form of communication and expression.

The textile traditions of Europe, on the other hand, did not appeal to Albers. The historical textiles Albers was accustomed to usually copied the narrative and figurative elements of painting, an approach Albers believed contributed to the low esteem of textile art.

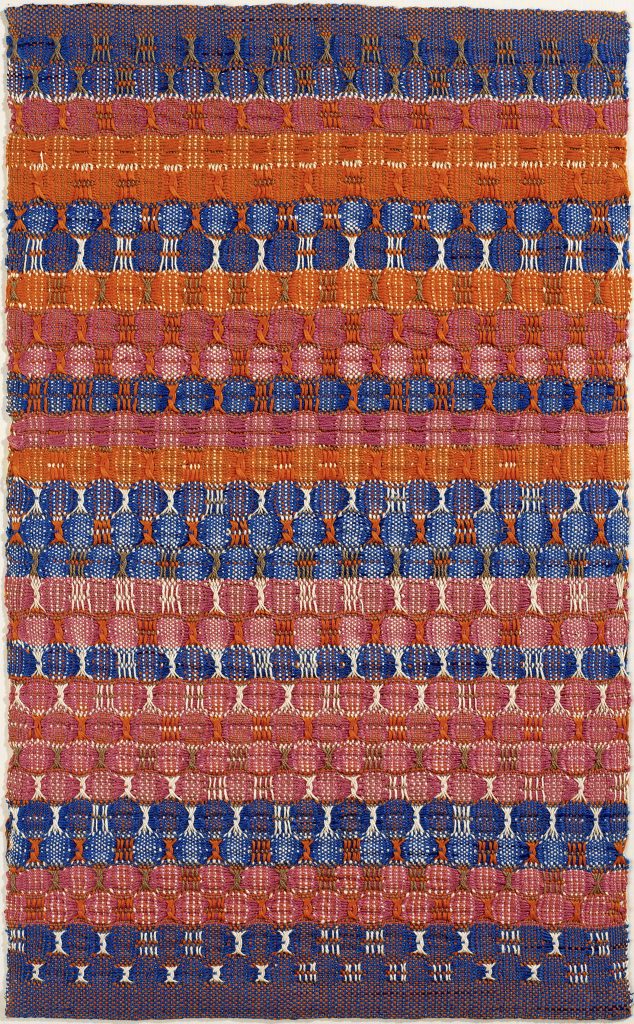

While thoughtfully embracing and subverting elements of the past, Anni Albers also looked to the future. She boldly demonstrated that museum-worthy modern art could be created by a woman at a loom, not just by a man with a paintbrush. In doing so, she transformed the role and scope of textile art in the 20th century.

Anni Albers, Hanging, cotton and silk, 1924, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation via Guggenheim Bilbao.

Galleries and museums didn’t show textiles, that was always considered craft and not art…. When it’s on paper it’s art.

Seven Life Hacks from Anni Albers, Tate, London, UK.

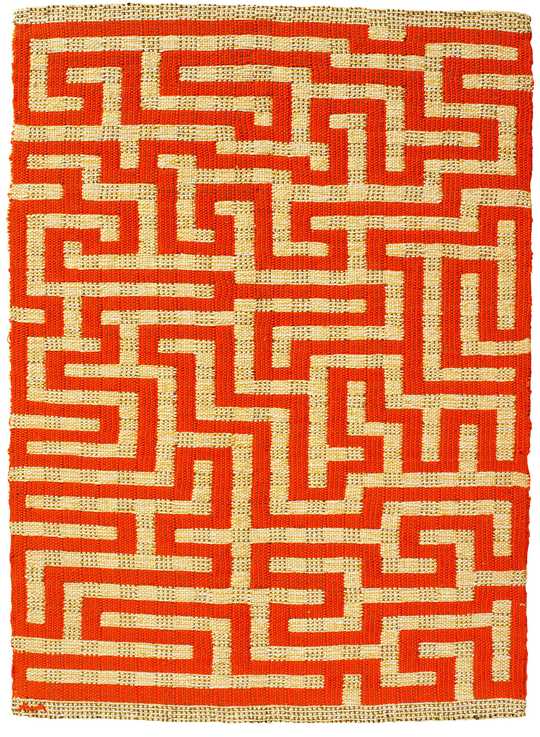

Anni Albers, Red Meander, 1954, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation via Tate.

As both a student and teacher, Albers elevated the reputation of textile art. What the Western world once considered a simple domestic craft began blossoming into a multifaceted fine art form. Indeed, across decades of creation and instruction, Albers demonstrated that textile art contained endless aesthetic and functional potential.

Albers also paid attention to the important knowledge and traditions of often-forgotten, non-Western cultures. Her published art historical and instructional writings, including On Designing (1959) and On Weaving (1965), are still prized by textile artists and educators.

As a textile artist, Anni Albers explored the rich relationships between form and function, as well as past and future. With unexpected geometric patterns, dynamic color combinations, and tactile textures, her work feels as fresh and modern today as when it was created.

Anni Albers, Blue and Red Capes, cotton, 1954, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation via Guggenheim Bilbao.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!