The National Portrait Gallery in London is due to close its doors starting 29 June 2020. The Inspiring People gallery re-development works will take three years. The gallery holds the most extensive collection of portraits in the world. In preparation for this long break, Daily Art Magazine would like to take you for a trip around the world inspired by the works available in the gallery’s extensive online catalogue. We’ll visit all continents and meet a host of fascinating people through their amazing portraits.

Today we’ll look at the climate extremes: the Middle East with its searing heat and Antarctica and Arctica to cool you down. The portraits were selected based on the location in which they were made or on the subject’s relation to a place.

Lawrence of Arabia

Lawrence of Arabia is, of course, the famous 1962 movie, awarded seven Oscars in 1963. It is based on real events and people, meaning that Lawrence of Arabia actually existed and most of his adventures are true. Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888 – 1935), was a British archaeologist, army officer, military theorist, diplomat, and writer.

Lawrence adopted Arab dress from the early days of his secondment to Emir Feisal. He worked with him as a British liaison during the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during WWI. He is seen here photographed by a member of the Royal Flying Corps at Wejh aerodrome, shortly before setting off on his journey through the Nefud desert to Akaba. After the war was offered both the Victoria Cross and a knighthood but declined the honors. His best-known work is Seven Pillars of Wisdom, an account of his participation in the Arab Revolt.

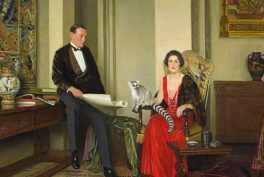

Sir Richard Francis Burton

Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821-1890) was a British explorer, geographer, translator, writer, soldier, orientalist, cartographer, ethnologist, spy, linguist, poet, fencer, and diplomat. Clearly, he was busy during his lifetime. Burton became famous for undertaking the holy pilgrimage to Mecca in 1853. Since he was a non-Muslim European, he did it in various disguises. He later published A Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah.

Frederic Leighton met Burton in 1869 at Vichy and they became lifelong friends. On 26 April 1872, Burton began sitting for his portrait. According to Lady Burton, he was difficult about it, anxious that his necktie and pin might be omitted and pleading with the artist, ‘Don’t make me ugly, there’s a good fellow.’ Apparently, the portrait was left unfinished in 1872 and not completed until 1875. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy the following year, but it is possible that Burton did not like it as Leighton kept it at his house in Kensington. Well-conveyed in Leighton’s portrait is the stern and decisive nature of Burton.

The National Portrait Gallery’s online catalogue accompanies each portrait with a brief note of the events taking place at the time of the work being created.

In 1872 George Eliot’s novel Middlemarch was published. Exploring the impact of the 1832 Reform Act on provincial England, and charting the changes in class, politics, art and science in the nineteenth-century. Eliot’s book is widely perceived to be one of the best examples of the English realist novel.

After the searing heat of the Middle East, it is time now to cool down at the globe’s extremities. Let’s jump south to Antarctica.

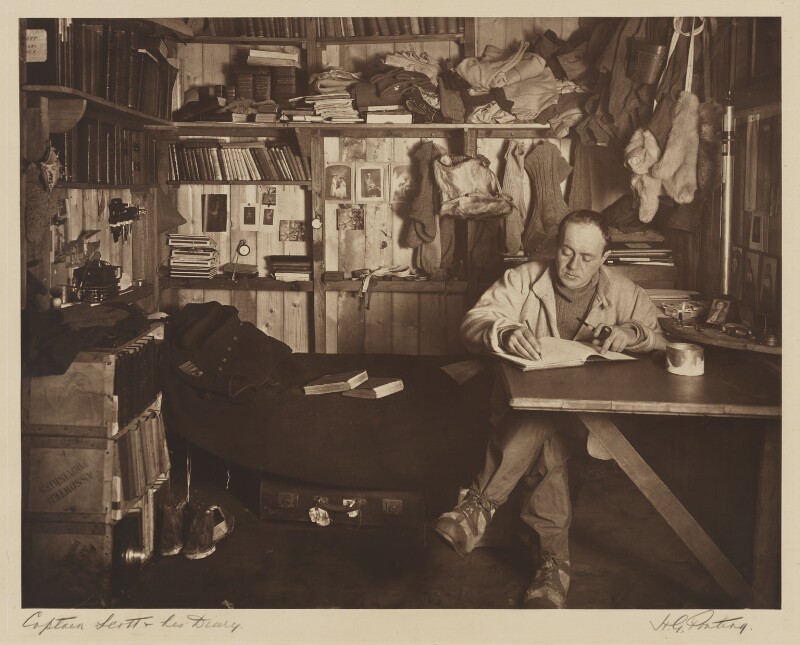

Robert Falcon Scott

Robert Falcon Scott (1868 – 1912) was a British Antarctic explorer. From 1901 to 1904 he led the first National Antarctic Expedition on board the Discovery, a ship also known as the Discovery Expedition. It made many significant discoveries in the areas of biology, zoology, geology, meteorology and magnetism. To continue this work, the Terra Nova Expedition launched in 1910. This time Scott sought to be the first man to reach the South Pole. He and four other members of the expedition arrived on 17 January 1912, only to discover that Roald Amundsen’s expedition beat them to it by 34 days. Scott’s entire party died on the return journey from the pole. Eight months later, the search party recovered their journals and some photographs.

For many years, no one questioned Scott’s status as a tragic hero. However, recent questions have arisen about the causes of the tragedy those deemed responsible for its occurrence, making Scott an increasingly fascinating figure, no longer solely as a tragic figure beaten to the pole by Amundsen. The story of the expedition is definitely worth exploring.

Herbert George Ponting was the official photographer of the expedition. Due to his illness, he left before its tragic end. He devoted the rest of his life to preserving records of the Discovery Expedition.

In 1911, Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre. The painting was missing for two years, during which the suspicion fell on avant-garde poet Guillaume Apollinaire and his friend Pablo Picasso. Finally, Vincenzo Peruggia, an employee of the Louvre, was arrested in Florence.

Now, let’s jump to the other pole: time for the Arctic.

Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (1786-1847) is obviously missing from this group portrait (why else would they be planning his search). He is, however, the link to the Arctic. The Admiralty sent out an expedition led by him in May 1845 to find a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. In 1847, the Admiralty, advised by the sailors and explorers depicted, decided to organize a search; only in 1854 it was discovered that the expedition had died of starvation. Pearce’s painting increased public interest in Franklin’s fate.

It was certainly Franklin’s last unlucky expedition, but not his first: In 1819, he led the Coppermine expedition. It aimed to chart the north coast of Canada eastward from the mouth of the Coppermine River. During the first year, he fell into the Hayes River at Robinson Falls and his men rescued him nearly 90 m downstream. Over the subsequent three years, he lost 11 out of his 20 men. The survivors had to eat lichen and even attempted to eat their own leather boots. Which gained Franklin the nickname of “the man who ate his boots.” I’m not sure I’d like to travel in such a company…

In 1851 Lizzie Siddal posed for John Millais’s painting Ophelia.

As mentioned at the beginning, in this series of posts we’ll be visiting all continents. Stay tuned for more exciting people whose portraits are in the National Portrait Gallery.

Read more: London’s National Portrait Gallery