12 Best Shots of the World Press Photo 2024 Exhibition

The World Press Photo Exhibition is a renowned annual event showcasing some of the most impactful visual photojournalism from across the globe.

Nikolina Konjevod 10 February 2025

3 September 2023 min Read

Staging an intervention in art history, and specifically in Indian miniature portraiture, Arpita Shah replaces male Mughal emperors with inspiring modern female muses of South Asian origin. As well as being sitters, these women are collaborators in this subversive series, in which they are elevated to the status of empowered subjects on their own terms.

Shah spent the earlier part of her life living between India, Ireland, and the Middle East before settling in the UK. This migratory experience is reflected in her practice, which focuses on the notion of home, belonging, and shifting cultural identities, often symbolized through clothing. Working between photography and film, Shah draws on Asian and Eastern mythology to explore issues of cultural displacement in the Asian diaspora.

Arpita Shah, Juwariyyah, Modern Muse series, 2019, Birmingham Museums Trust, Birmingham, UK. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2019, Shah was commissioned by GRAIN to create a photographic series, titled Modern Muse. In her research for it, the artist recognized that South Asian women, in traditional imagery from colonial times, are typically framed as passive and subservient characters in paintings:

Historically, Mughal women did play crucial roles in that period, however, they were often sensually portrayed, as a consort or a lover, through the eyes of a male artist.

In the interview with the author.

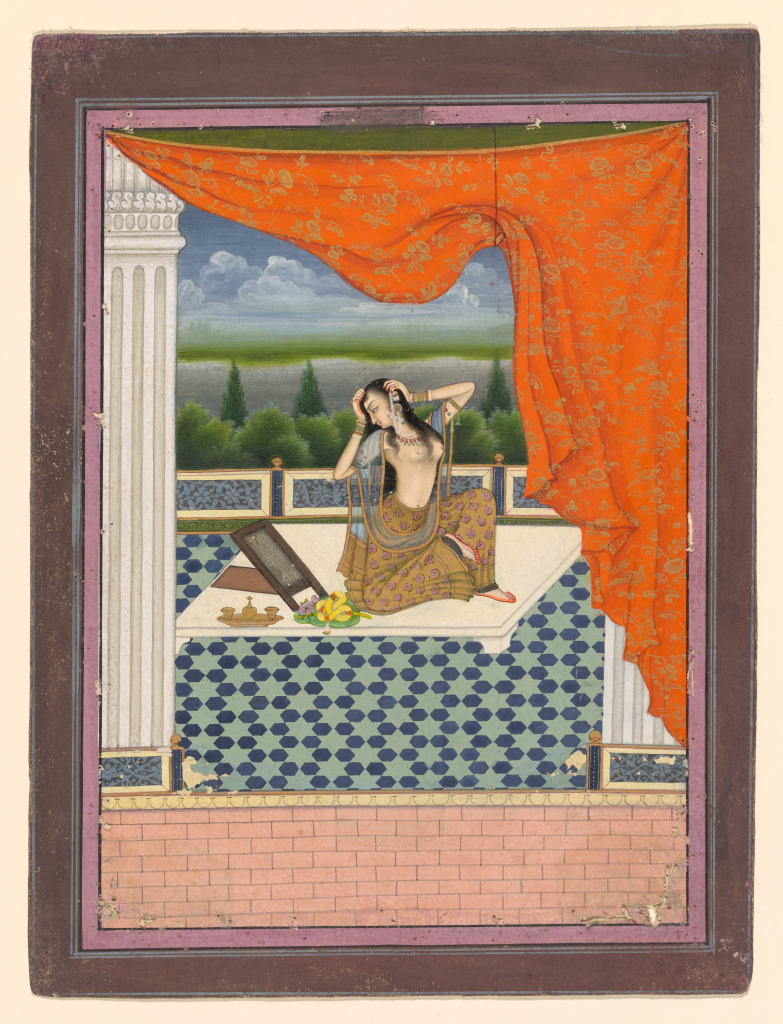

Mughal School, Heroine Arranging Her Hair while Awaiting Her Lover (Vasakasajja Nayika), early 19th century, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

In an early 19th-century watercolor from the Mughal School, Heroine Arranging Her Hair while Awaiting Her Lover (Vasakasajja Nayika), a drawn curtain reveals a semi-undressed figure in her bedroom, preparing for an evening with her lover. Other paintings present anonymous women in sensual postures, waiting in gardens for their lovers while holding the suggestive narcissus flower, or reading a book of love poetry, holding a cup of wine, or looking at themselves in a bedroom mirror with admiration in their eyes. The contours of these young women’s bodies are revealed to the viewer through luxurious, transparent clothes.

Shah sought “to challenge these narratives” with her female gaze, and chose to “deliberately replace the Mughal emperors with portraits of modern British Asian women”, all living in the West Midlands, and working across arts, culture, and education. She was already connected with many of them online or had previously met at arts events. Meanwhile others responded to an open call posted on social media. Her muses include an artist, academic, activist, dancer, and educator.

Arpita Shah, Haseebah, Modern Muse series, 2019, Birmingham Museums Trust, Birmingham, UK. Courtesy of the artist.

In order to subvert the objectification of South Asian women, Shah invited her sitters to express their confidence through a more direct gaze and pose, akin to those held by male emperors and rulers. Furthermore, they are positioned alone against colorful backgrounds in miniature portraiture. Beginning in the 17th century, individualized portraiture began to flourish in Mughal India and, although women were anonymized, men of status were named and celebrated through their likenesses of them.

Portrait of Emperor Shah Jahan, c. 1680, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

Shah Jahan, best known for commissioning the Taj Mahal as a tomb for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, was frequently depicted in paintings. One such example is this watercolor, in which he is shown with a halo—a symbol of divinely ordained royalty. Meanwhile, in an 18th-century Portrait of Raja Surajmal of Bharatpur (1707–1763), the ruler is identified by his characteristic long and short swords, symbolizing his political savvy and negotiation skills.

Portrait of Raja Surajmal of Bharatpur, 18th century, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

Taking inspiration from these portraits of renowned male Mughal leaders, Shah asked her muses “to bring in clothes that best represented their style and their identity”. Much like the hunting coats, jewelry, and swords that mark an emperor or sultan’s status in miniature painting, fabrics are an important part and signifier of Shah’s muses’ multifaceted identities. Many of the women wear both traditional Asian garments and Western clothing as a means of expressing their interwoven cultural heritage. They also openly discuss their relationships with these items, including the headscarf, with the artist behind the camera.

Arpita Shah, Jaskirat, Modern Muse series, 2019, Birmingham Museums Trust, Birmingham, UK. Courtesy of the artist.

In fact, stating that the Modern Muse series is not just about, but “for” her sitters, Shah interviewed each woman. She noted that they all “have something to say”, which is why she selected them for the project. These recorded conversations and statements are included in a publication of the same name that accompanies the series, as a means of giving the muses “more agency”. Many of them reflected on their choice of clothing for the photo shoot.

Sikh artist Jaskirat Kaur, who was born in the UK and whose family are from Punjab, Northern India, explained:

“I was born in the UK, my family is from Punjab, Northern India and we are all Sikhs. I like it when people ask and are curious about my Dastar (turban), rather than keeping that curiosity within and not exploring it. I enjoy talking about my identity, so am open to people asking me about it. Personally, the Sikh Dastar shows that you’re loyal to Guru Nanak Dev Ji. I am covering my kes (hair) because it is one of the five gifts in Sikhi. Covering, growing and never cutting your hair ensures you retain the flow of energy in your body. It is really important when you meditate to keep it intact and coiled on the top of your head. Covering your kes is also respectful, hygienic and practical for meditation and focus. I am proud to be Panjabi and from the land of the Gurus that laid the foundation of Sikhi. I identify as being from the UK but my home is also Punjab.”

Arpita Shah, Kasi, Modern Muse series, 2019, Birmingham Museums Trust, Birmingham, UK. Courtesy of the artist.

Meanwhile, Kasi, who works in finance while blogging, consciously presents her heritage and religious identity through fashion:

“Since turning 30, and spending the last 3 years in the Midlands, I am more aware of how I carry myself, how I make sure that I show that I am Indian and Sikh. This is where I come from. One thing I make sure of is that I wear a Bindi, no matter what else I wear…I can merge my two cultures – with makeup, with jewelry and with clothes and show who I am. When I was younger I used to go to Punjabi School on Saturdays and was embarrassed to wear a Shalwar Kameez suit to just walk up the High Street in, but now I’m proud of it.”

Portrait of a Mughal Princess, 17th/18th century, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

While riffing on Indian miniature portraiture, Shah also works with her muses to challenge reductive and colonial narratives with her inside gaze. She rebuffs historical Orientalist paintings by the likes of Ingres and Delacroix, in which Asian women are portrayed as an exotic, eroticized “other” on display for the male viewer. Her series also stands against more contemporary mythologies, constructed by the media and photographers, in which veiled women are presented as oppressed subjects in need of saving.

Instead, Shah’s muses, like the male Mughal emperors, own their own space inside the frame, proving that each has a distinct identity and story. At the same time, the series importantly honors them as a collective and sisterhood of unified South Asian women, all from Birmingham and the West Midlands, a region shaped by its rich multicultural heritage. As such, they recall the nine divine muses who, in ancient Greece, bestowed inspiration upon artists.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Lady of Pity, 1881, Birmingham Museums Trust, Birmingham, UK.

While invoking these goddesses from mythology, Shah modernizes and diversifies notions of the muse, as framed by Western art history and popular culture. The term Muse typically brings to mind a beautiful, auburn-haired, white women, such as Elizabeth Siddall, Jane Morris, or Joanna Hiffernan, who have been immortalized in museum-worthy masterpieces.

As a South Asian artist, it was important to challenge representations of South Asian women in Mughal Indian miniatures, but also comment on the visibility of women of color in Western representations of the “Muse”. I made Modern Muse for South Asian girls and women, for them to feel represented. I hope more than anything that this series of portraits and each muse’s words will resonate with some of the museum visitors and inspire them – in the same way, each muse has really moved me.

In the interview with the author.

Recently acquired by Birmingham Museums Trust, Shah’s Modern Muse series joins the city’s civic collection which includes world-leading Pre-Raphaelite masterpieces. Alongside paintings and drawings of more traditional models, Shah’s subjects will each play a critical role in expanding audiences’ understanding of who deserves to be seen as an artist’s inspiring muse, with their own unique story to be shared.

Author’s bio

Ruth Millington is an art historian, critic, and author, specializing in modern and contemporary women artists. She has been featured as an art expert on radio and TV, including BBC Breakfast, Sky Arts and ITV News. Ruth has written for national newspapers, including the Telegraph, the I and The Sunday Times. Her first book Muse uncovers the hidden figures behind art history’s masterpieces. Here you can read our review of the book. You can follow her on Twitter at @ruth_millington.

Also, here you can read Ruth Millington’s other guest article about Mary Blair, a woman artist behind Walt Disney’s magic!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!