Summary

- South Africa is infamous for its time of apartheid. Several political scientists argue it only came to an end once a sufficient number of South Africans were empowered. Art played an important role in reaching this.

- Art that was produced in this period was labeled “resistance art.” It sought to challenge the government without constraint. Paint and words became weapons.

- The government feeling threatened, introduced the Suppression of Communism Act in the hopes of silencing the influential artists.

- Nevertheless, art proved to be more powerful. The political campaigns led by the ANC and PAC were accompanied by songs, awareness was spread through photography, and suffering was conveyed in paintings.

- Art became the voice of the silenced, it built up a torn community and it brought the strength needed to mobilize the suppressed majority. This helped bring the downfall of the National Party in 1994

Ranwedzi Nengwekhulu (1976) and Stephen Zunes (1999) write that the downfall of apartheid was only successful when a sufficient number of South Africans were empowered. But what helped bring about said movement, involvement, and strength? Among other things, art.

“Apartheid” means separation and it presented the most elaborate system of internal colonialism. Nevertheless, there was an interesting paradox where the government was both powerful and vulnerable. It was powerful due to its resources and strength, but vulnerable because it was dependent on the submission of the 80% Black majority in order to hold on to its repressive political system. This dependence is what gave non-violent resistance its power. Non-violent action can be understood as “unconventional acts implemented for purposive change without intentional damage to persons or property.” It comprises boycotts, sanctions, demonstrations, and other forms of civil disobedience.1 It also includes the use of arts, both visual (painting and photographs) and verbal (songs and poems).

National Non-Violent Action

Before discussing the artistic movements, it is important to have an overview of what other forms of non-violent action were taking place in the struggle against apartheid. Within the country, the role of the ANC, PAC, and BCM were paramount in all political and activist movements:

- The African National Congress (ANC) – the main political organization through which Black South Africans fought for their rights. In 1952 it launched the Defiance Campaign, led by Albert Luthuli. Large crowds peacefully, but deliberately broke “unjust” laws as a protest.2

- In 1954 a group within the ANC broke away and formed the Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC). After PAC organized a peaceful protest in Sharpeville in 1960, resulting in the Sharpeville massacre (69 civilians killed), both organizations were banned.3

- In 1968, resistance took a new form with the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM), led by Steve Biko. It encouraged Blacks to be proud of their identity (“Black is Beautiful”) while rejecting foreign values that had been forced upon them.4

- The ANC revived after the Soweto Uprising in 1976 (600 students killed by police), adopting many aspects of the BCM. Non-violent resistance culminated in the New Defiance Campaign of 1989.5

There was an understanding that the most powerful weapon of the oppressed was their minds. The non-violent struggle against apartheid would prove to be successful when enough people were empowered and no longer docile to exploitation.

However, the role of art in the process of overcoming apartheid seems not to be sufficiently studied. Arts played an important role in giving the ANC, PAC, and BCM a powerful tool to spread awareness and Black civilians a way to feel identified and empowered. It gave the possibility for everyone to be involved in the struggle.

We want to make South Africa white.

Africa Today, “Partners in Apartheid: U.S. Policy on South Africa”, Africa Today 11, no. 3 (March 1964), 2.

Role of Art in Empowering the Oppressed

Art has always been a tool for social progress, from documenting history to conveying collective emotions. In the case of apartheid, millions of South Africans were silenced and suppressed for years. Art played a very important role in empowering the oppressed and making the community proud of their identity and worth. Black South Africans, coming to this realization, were the biggest threat against the government.

Art that was produced in the period of apartheid, critiquing the state’s racial and unjust policies, was labeled as “resistance art.”6 This type of art lost its innocence, tackling unjust issues without visual or verbal constraint. Paint and words were used as weapons, producing political work and celebrating Black unity and strength. Furthermore, it helped create awareness, inspire action, and build a movement.

The government, feeling threatened, took advantage of the Cold War tensions to introduce the Suppression of Communism Act.7 With this legislation they were allowed to persecute countless artists resulting in censorship, exile, arrest, torture, and murder.

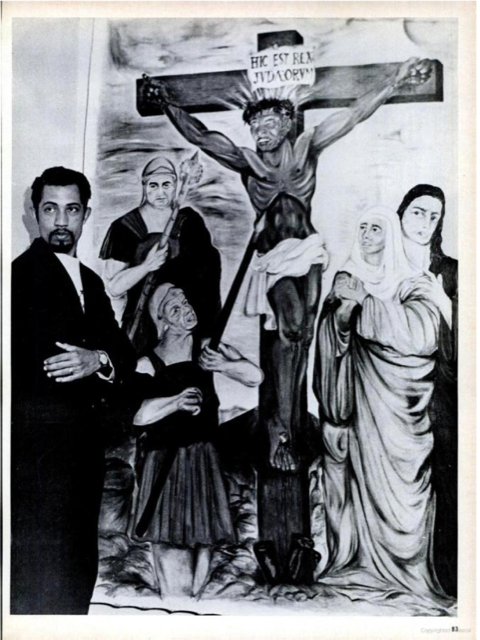

Ronald Harrison next to The Black Christ, 1961 via Weaver, “Art against Apartheid”, p. 7.

Visual Arts

An example of South African resistance art is the painting The Black Christ (1961) by Ronald Harrison. After the Sharpeville massacre, Harrison had had enough of the injustices in South Africa. He said: “There must be something I could do, must do, and will do! Ringing in my ears was the saying, ‘The pen is mightier than the sword, but a picture paints a thousand words.’”8 He believed that meaning and emotion could be conveyed through art, which would lead to action and change.

Through this painting he portrays the suffering of the oppressed, sending a clear message to fellow South Africans. “All races that were not classified “white” – were being crucified.”9 He made a provocative statement by painting the National Party leaders, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd and Balthazar Vorster, as the executioners of Christ. The government consequently banned the painting, demanded its destruction, and also interrogated and tortured Harrison.10 This violent reaction highlights how this piece, showcasing the plight of Black people, was considered a threat to the system.

Hector Peterson carrying Mbuyisa Makhubu in Soweto. Photographed by Sam Nzima, 1976 via Shaped.

Sam Nzima

Sam Nzima was a photographer for World and was assigned to document the Soweto student protest. He took one photo that touched the whole country. It depicts 13-year-old Hector Peterson, the first victim of the police shooting, carried by 18-year-old, Mbuyisa Makhubu, with Hector’s sister following in despair. The newspaper published this image and it was distributed throughout the country. It became the straw that broke the camel’s back, repeatedly used as a reference by both the ANC and PAC. The police banned the picture, put Nzima under house arrest, threatened to kill him, and disposed of his film. Also, to this day Makhubu is nowhere to be found.11

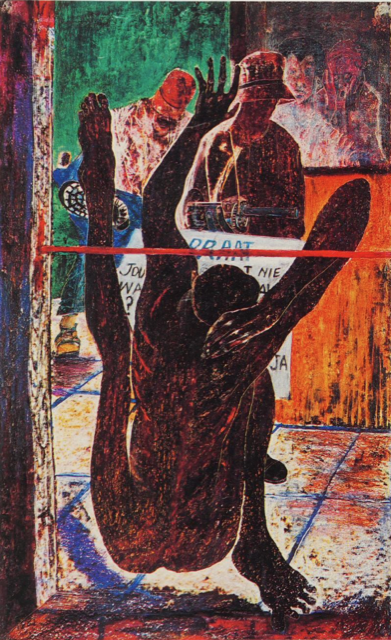

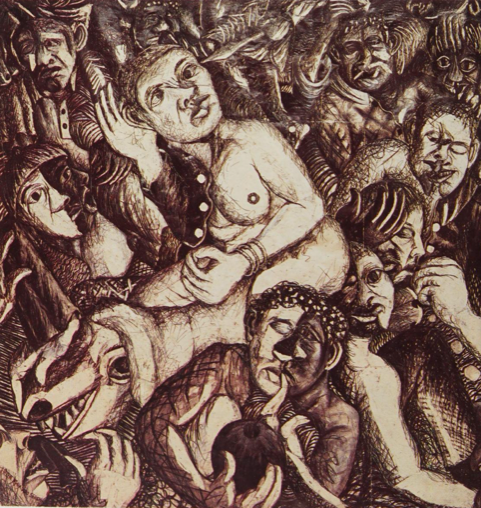

Thamsanqa “Thami” Mnyele, Women Unite Against Apartheid, lithograph, 1981, Art Insitute Chicago, IL, USA.

Thamsanqa “Thami” Mnyele

Thamsanqa “Thami” Mnyele worked mainly in prints and believed that “the act of creating art should complement the act of liberating the country for me people.” He considered art as a tool to eliminate the exploitation of Black South Africans. He called for everyone to express their demands and resistance through the use of paint and brushes. Thami was forced into exile in 1979 because the state saw him as a menace. However, he continued to be the voice of Black African artists by joining the ANC, chairing the Gaborone Culture and Resistance Festival (1983) in Botswana, and speaking at a conference in Amsterdam the same year. Thami was shot dead by South African police outside his home in Gaborone in 1985, his art pieces were taken, and his house was burned down. The state considered his work as being part of “terrorist activities.”12

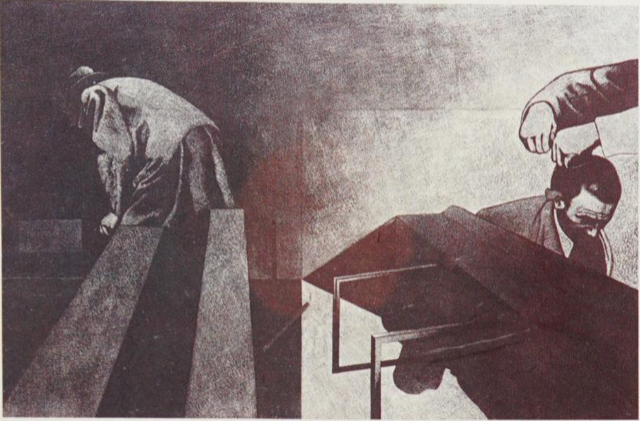

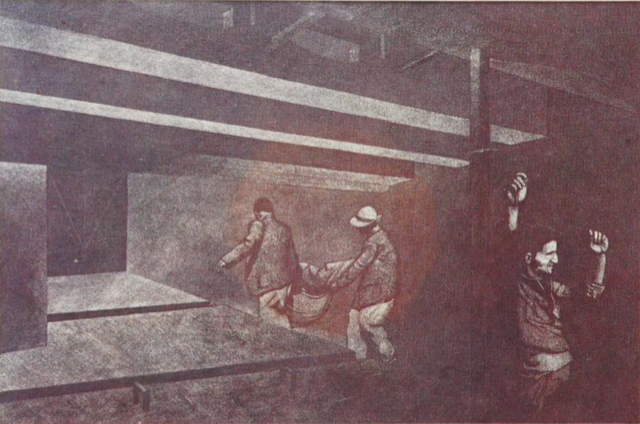

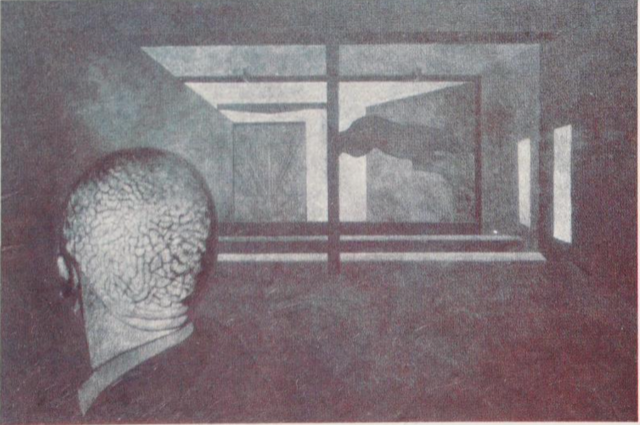

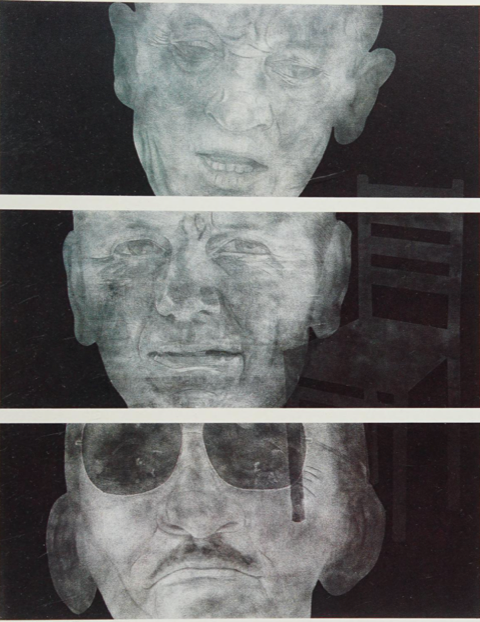

Paul Stopforth, The Interrogators, 1979, via CAA.

Paul Stopforth

Paul Stopforth’s art was composed of wax figures, graphite, and acrylics. The Interrogators depicts the policemen that “interrogated” BCM leader Steve Biko. Biko was found dead in 1977; he was tortured for 18 days. Elegy is the title of a series of 20 works by Stopforth in homage to Biko.13 It is a composition of naked figures in positions of suffering and torture: hooded, trussed, and strung from a pole. Interrogation Spaces shows the murky places where these violations were taking place.14 Stopforth focused on the acts of violence the government was encouraging against the leaders of the liberation movement. He held the state accountable by showing the real faces of the violators.

Paul Stopforth, part of Elegy series, 1980 via CAA.

There are countless more artworks that express what people felt and the change they sought. Mpolokeng Ramphomane made Eyewitness after his house was raided at gunpoint by the police demanding rent.15 Mmakgabo Mmapula Helen Sebidi created Tears of Africa showcasing how the Black community was not able to breathe in the oppressive society.16

Art became so widely used that even children resorted to it in order to convey what they were experiencing. “They shot the son dead in the house and the mommy is running to him” was the description of the blue drawing below. “Something seen recently” was the explanation for the clay figure made by a 9-year-old.17

Verbal Arts

Verbal art was another important tool in the struggle against apartheid. Freedom Songs were used to move and bring people together. They were sung during protests and political meetings. The lyrics celebrated political victories, unity against apartheid, and mourned those who had been killed.

Two of these songs stand out: Nkosi Sikelel’l Afrika (God Bless Africa) and Somlandela (We Will Follow). The former was considered the anthem of anti-apartheid resistance, later becoming the anthem of South Africa.18 One stanza goes:

Sounds the call to come together,

And united we shall stand,

Let us live and strive for freedom,

In South Africa our land.

It offers a message of unity and inspiration. By singing “the call to come together,” and “united we shall stand” there is a cry for collective empowerment and strength against suppression.

Somlandela celebrates the commitment of the leaders of ANC and the organization itself, especially President Luthuli. It was sung in the Defiance Campaign while the protestors were being brought to jail.19 One stanza goes:

We shall follow Luthuli.

Luthuli.

We shall follow him everywhere.

he goes,

The jails are full, they show that we struggle for our freedom.

The lyrics show the commitment and trust of the people in the ANC, seeing Luthuli as their leader towards liberation and freedom.

Musicians played a prominent role too. Miriam Makeba became known as Mama Afrika, singing openly against apartheid. She used her voice to describe the unpleasant realities Black South Africans were experiencing.20 One of her songs, Soweto Blues (1977), describing the Soweto Uprising, goes:

They are killing all the children,

Without any publicity,

Oh, they are finishing the nation.

She criticizes how the government tried to brush off the events when, in reality, it was “finishing the nation.” It is a powerful song, with strong, controversial lyrics conveying sorrow, anger, and strength. Makeba proved to be successful when the government tried to silence her. In 1960, she was denied entry into the country. Then in 1963, her records were banned and her passport was revoked. However, she was not silenced. The same year she spoke and sang for the oppressed at the UN Special Committee against Apartheid.21

Poets also used words as weapons. Mongane Wally Serote’s poems No Baby Shall Weep and Behold Mama, Flowers talk about violence, death, exploitation, and the Blacks’ search for a sense of community and identity.22 Fellow poets such as Dikobe Ben Martins and Vuysili Mini also participated in the war against apartheid through words, influencing hearts and minds. All three were influential in the BCM and the ANC. The government, seeing the threat of art, reacted with violence. Serote was arrested and kept in solitary confinement in 1969, and later barred from the country in 1977. Martins was arrested and tortured in 1983. Mini was condemned to death and hanged in 1964. The government said they were participating in “terrorist activities.”23

At no time has the liberation movement not been singing.

Apartheid Museum and Mary Monteith, Understanding Apartheid, Oxford University Press Southern Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, 2006.

Art was a tool to bring people together, as seen when Somlandela was sung in taunt during the Defiance Campaign led by the ANC. It helped portray the suffering of the whole Black community (including children), as with “Tears of Africa.” Furthermore, it was a way to spread awareness as with the photo by Nzima. Art was a strategy to build up a destroyed, torn community. It brought strength and unity to mobilize the majority against the minority. Art became the voice of the silenced, which was essential for the downfall of the National Party and the end of apartheid in 1994.

Author’s bio:

Diene Anais Grapengiesser is a recent International Relations graduate from King’s College London. Her fields of interest include political economy and Sub-Saharan African politics. Although she is pursuing a career in the former with a master’s at UC Berkeley, she continues researching on the nexus between art and world politics.