Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

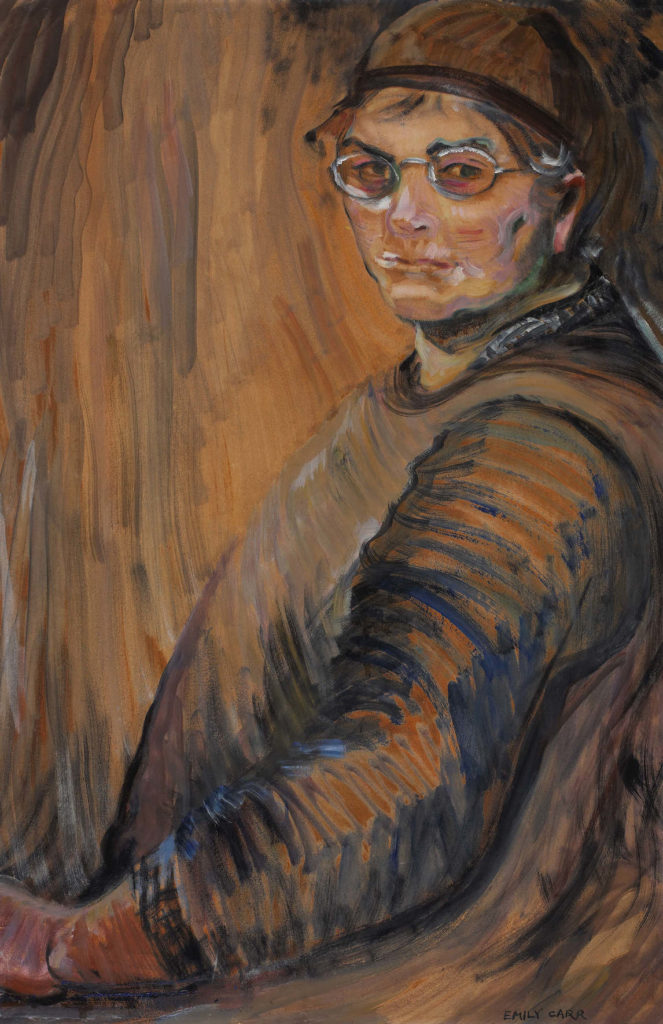

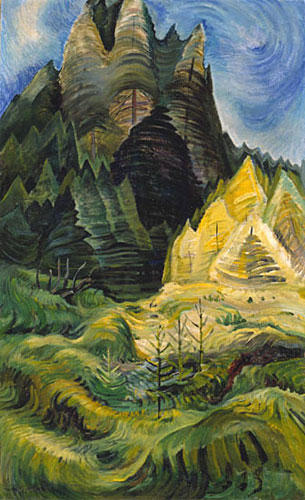

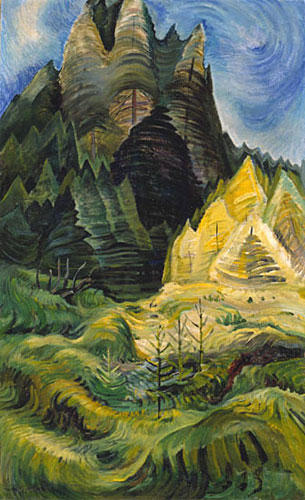

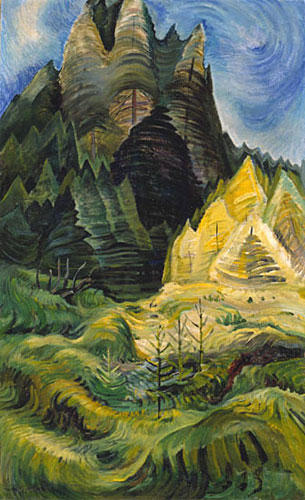

Art has always had the power to communicate all kinds of emotions; some paintings convey a sense of peace and quiet, while others can make us feel upset or uncomfortable. The latter gives us awareness about something that is wrong in our society, something that we could change or stop. That is why we can somehow feel guilty viewing those works. This is the case with Emily Carr‘s last artworks. They represent her concern about the environmental impact of Canadian industries and make us think about the current climate situation.

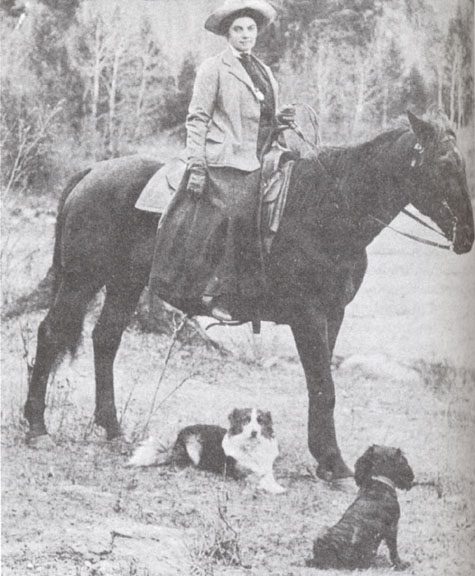

Emily Carr was born in 1871 in Victoria, British Columbia. Her father, an English entrepreneur, had always wanted his daughters to have a good education and to be independent. However, he was also quite strict and authoritative, giving Emily a sense of rebellion and alienation at a young age.

When her parents died she decided to move away, studying in San Francisco and later in London. The city she loved the most was Paris where the works of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Fauvist artists inspired her.

In 1907 she took a trip to Alaska with one of her sisters. This inspired her interest in environmental issues and in Native American people. Carr later saw that she couldn’t stand living in big cities and needed to be in the vast, open Canadian wilderness. After that first trip, Carr began a documentation project and traveled to the islands of the Northwest Coast. About those journeys, the artist wrote in her journal:

Whenever I could afford it I went up North, among the Indians and the woods, and forgot all about everything in the joy of those lonely, wonderful places. I decided to try and make as good a representative collection of those old villages and wonderful totem poles as I could, for the love of the people, and the love of the places, and the love of the art.

Emily Carr, Opposite Contraries: The Unknown Journals of Emily Carr and Other Writings, ed. Susan Crean (Vancouver: Douglas& McIntyre, 2003).

If you are interested in artists who celebrated nature in painting their country’s landscapes read about The Hudson River School here!

In the following years, Emily Carr kept exploring British Columbia, painting its landscapes and native villages. In 1927 Eric Brown, the director of the National Gallery of Canada asked her to join the Group of Seven (a Canadian progressive and nationalistic school of painting). He was actually organizing a huge show about Canadian West Coast Art. Thanks to this exhibition Carr finally obtained the national recognition she was aspiring for.

One of Emily Carr’s most peculiar characteristics was her rejection of the Church and other religious institutions. She created her own vision of God, seen as nature, and believed in it until her death in 1945.

In the last decade of her life, Emily Carr started noticing disturbing changes in the landscapes she loved to paint; industries were replacing forests. Indeed, one of the major natural resources of Canada was (and still is) forestry, covering 26.5% of the national surface.

In Canada, the process of industrialization started in the second half of the 18th century. Newborn industries heavily exploited the natural resources of the country, regardless of how this could affect the environment. This also had a strong impact on the lives of Indigenous people whose lands were destroyed.

At that time the concept of environmental awareness was not as evolved as it is today, so you can see how progressive Carr’s position on it was!

One of Emily Carr’s artworks that exemplifies her worries about the logging industry is Odds and Ends. It is painted in a Post-Impressionist style, with separate, strong brushstrokes. In it, Carr depicts what is left of a forest. While the trees in the background are blurred and seem to blend into the surroundings, we are immediately drawn to those in the foreground; there is an absence of trees, trees reduced to stumps, and the six trees remaining to stand out.

Therefore, we can observe how unusual the contrast is between the sky and earth. Whereas the ground almost seems to be fluid and has dull colors, the sky is represented with brushstrokes that remind of one of the tears, with strong and intense shades of blue.

Emily Carr didn’t want her work to be realistic, but to make the viewers feel something that she described wonderfully in her journals:

There’s a torn and splintered ridge across the stumps I call “the screamers”. These are the unsawn last bits, the cry of the tree’s heart, wrenching and tearing apart just before she gives that sway and the dreadful groan of falling, that dreadful pause while her executioners step back with their saws and axes resting and watching. It’s a horrible sight to see a tree felled, even now, though the stumps are grey and rotting, As you pass among them you see their screamers sticking up out of their own tombstones, as it were. They are their own tombstones and their own mourners.

Emily Carr, Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1966).

If we observe the painting carefully, we can almost hear the screams of the stumps in the silence. Rather than a forest, the landscape seems to represent a graveyard or a crime scene. The artist wanted us to see how nature can be transformed into something unnatural. The message we get isn’t one of progress and modernity. It is one of the abuse and exploitation of something which we will never have full control over and that one day will turn against us.

Currently, almost a century later, we are facing the consequences of this environmental exploitation. It has grown more and more and concerns every natural resource we have on Earth. We pushed our planet to a limit that we cannot exceed.

Emily Carr had promptly understood that the logging she was witnessing would lead to something bigger and more horrible. We see it every day when people walk through our cities with anti-smog masks, or when we watch the news and see countries destroyed by fires or floods. We need to understand that this is not normal, and we cannot let it become the normality.

In 1939 there was plenty of time to stop climate change but there wasn’t awareness about it, also science and technology were not as advanced. Now, in 2022, we have the awareness and the tools, but we are running out of time.

Things have now gone so far that making changes in our personal lives is not enough. What we need are major changes in our society and economy to let us live with zero environmental impact.

Emma Marris, an environmental writer, wrote a useful and interesting article in the New York Times. She points out that we can still solve the climate crisis, but only if we join together. The youngest generation, which is the greatest victim of the climate crisis, already did. Movements like fridays4future are now fighting for older generations to understand the gravity of this situation and to do something.

It is important to fight for this important and just cause. There are many apolitical organizations based on science that want to ensure a future for all of us, you just have to choose one.

It is good to try to make small changes in our personal lives, but we also need politicians and companies to make bigger ones; the only way for that to happen is to make our voices heard.

Remember that fighting for climate change means also fighting for equality and justice. As Marris writes:

This future is still possible. But it will only come to pass if we shed our shame, stop focusing on ourselves, join together and demand it.

Also, I would add, don’t forget to let the art inspire you while you fight!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!