Art on Screen: 12 Movies about Artists Worth Seeing

Whether troubled or exciting, extraordinary or perfectly average, the lives of artists are an endless source of inspiration for cinematographers.

Edoardo Cesarino 17 February 2025

The year 2023 marked the 60th anniversary of Doctor Who, a British sci-fi show about a runaway alien Time Lord that’s now beloved worldwide. Fans were treated to three anniversary specials with David Tennant reprising his role as the face-changing Doctor. In celebration, let’s take a look at art in Doctor Who. Thanks to the Doctor traveling through time and space, the show has had a few brushes with both art and history.

Allons-y!

Let’s begin with an episode where art is an explicit part of the story “Vincent and the Doctor,” which brings the Doctor face-to-face with Vincent van Gogh. The adventure starts with the Doctor and human companion, Amy Pond, visiting the Musée d’Orsay in the present day. All seems well until the Doctor spots an anomaly in one of the paintings: an alien creature lurking in a church window.

Still from Doctor Who, “Vincent and the Doctor”, S5E10. Doctor Who/BBC.

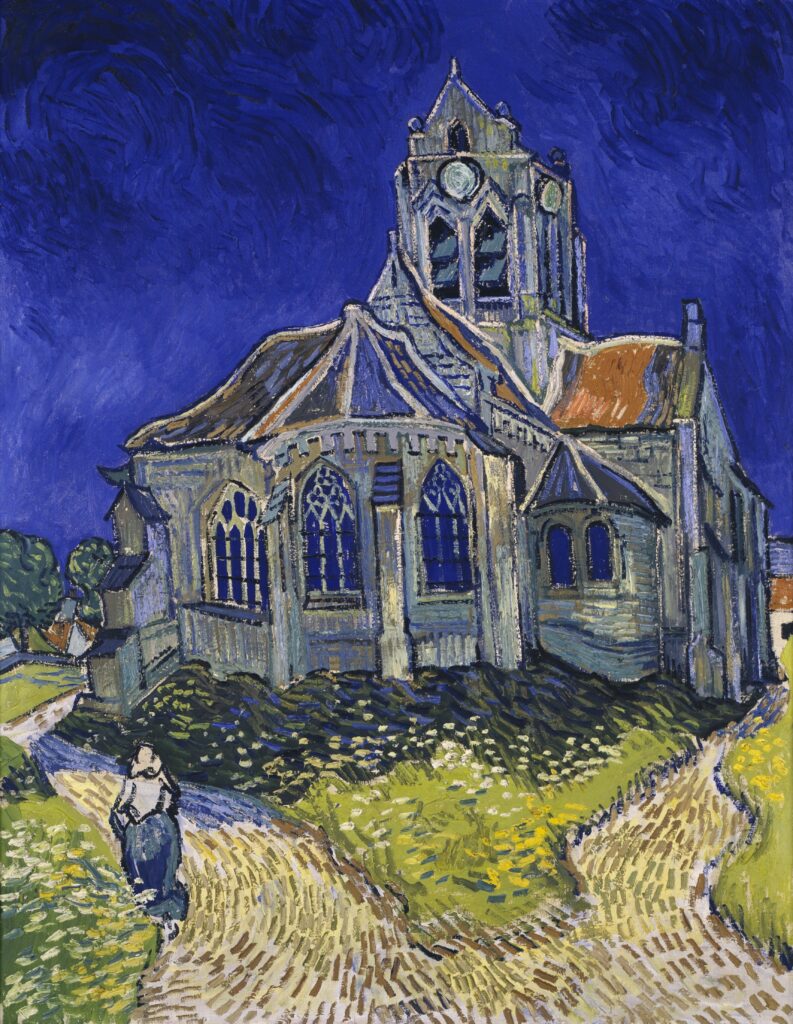

Vincent van Gogh, The Church at Auvers, 1890, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

The window is taken from a particular Vincent van Gogh’s painting, The Church at Auvers (1890). But when the Doctor travels back to 1890, the glimpsed monster plot becomes secondary to learning about Vincent as a person.

Elements of Van Gogh’s life are treated with humor, such as his home being overrun with sunflowers. Also, the episode gives a further cheeky wink to the audience when Vincent attempts to gift the Doctor a self-portrait. He remarks, “I only wish I had something of real value to give you.” Now viewers are prone to agree to disagree, as his self-portraits have become an indispensable part of the modern art canon.

The love and respect within these references are clear. The crew transports us into Van Gogh’s world, where the beautiful mise-en-scène brings his artworks to life, like his iconic bedroom.

Art references to Vincent van Gogh’s Bedroom in Doctor Who, “Vincent and the Doctor”, S5E10. Doctor Who/BBC.

Vincent van Gogh, Bedroom (3rd version), 1889, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

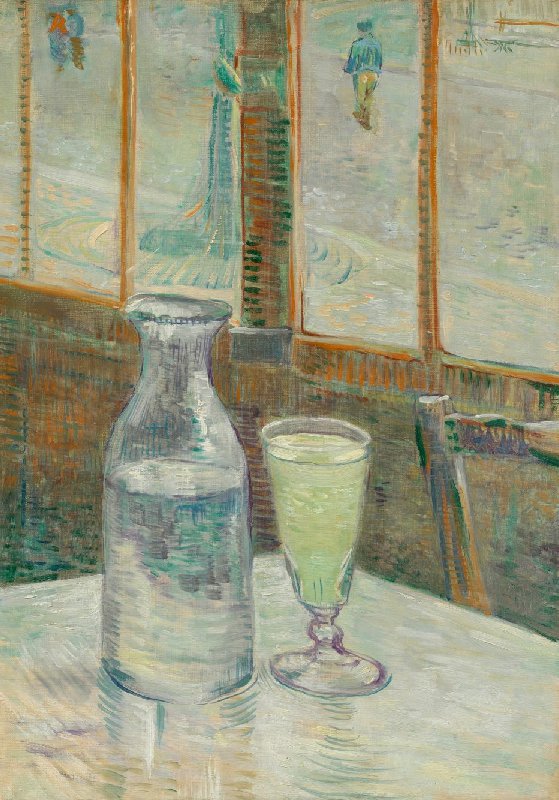

Furthermore, other famous pieces are featured as imperfect works in progress, highlighting Vincent’s presence as an artist as well as a human being.

Art references to Vincent van Gogh’s Café Table with Absinthe in Doctor Who, “Vincent and the Doctor”, S5E10. Doctor Who/BBC.

Vincent van Gogh, Café Table with Absinthe, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

There’s an overall poignancy to “Vincent and the Doctor.” 1890, the year that the Doctor and Vincent van Gogh meet, is also the year of the artist’s untimely death. However, Doctor Who does not shy away from this painful fact. The episode, comprised of thoughtful artistic references, is both a love letter to Vincent van Gogh and a reflection on the impact art can have long after the creator’s death.

The Doctor is, of course, no stranger to meeting famous historical figures. Another such instance is the episode “The Girl in the Fireplace.” Through a time portal in a fireplace, the Doctor travels to 18th-century France. Then, he meets Reinette, or, as we may know her, Madame de Pompadour, mistress and advisor to King Louis XV.

While the Doctor Who story itself shows Reinette being just as captivating as the status surrounding her would suggest, this is also conveyed through the visual art featured in the show. An oil portrait was created specifically for the episode by artist Amanda Clegg. Clegg used a portrait of Madame de Pompadour by François Boucher as a reference.

Amanda Clegg, Madame de Pompadour (as seen on Doctor Who) oil on wood panel. Art by Amanda Clegg.

François Boucher, Madame de Pompadour, 1756, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany.

The inspiration Clegg drew from Boucher is clear, with Reinette portrayed in a strikingly similar dress: sumptuous silk folds in shades of teal adorned with flowers. Additionally, in Clegg’s work, Reinette’s right hand rests delicately, partly resembling the pose Boucher painted. One notable difference in Clegg’s portrait is that it was made to bear the likeness of Sophia Myles, the actor who portrayed Reinette in “The Girl in the Fireplace.” Another distinction is that Madame de Pompadour is facing the viewer directly. She wears a determined, knowing look, suggesting that she is well-prepared for the chaos of the Doctor entering her life.

More famous than its depictions of historical figures are Doctor Who’s monsters. Today, we’re focusing on those chilling creatures that leave people terrified of statues: the Weeping Angels. Dubbed by the Doctor as “the lonely assassins,” Weeping Angels attack by sending humans back in time, dooming them to live and die in eras that are not their own. To stop the deadly fast Weeping Angels, one has to look at them without blinking. Soon after, they will turn to stone.

Your life depends on this: don’t blink! Don’t even blink. Blink and you’re dead. They’re fast, faster than you can believe. Don’t turn your back, don’t look away, and don’t blink.

Doctor Who, ‘Blink’, S3E10

Still from Doctor Who, “Blink”, S3E10. Doctor Who/BBC.

With their angelic form and stony appearance, the Weeping Angels bear a resemblance to some Victorian statues. Appropriate enough, one of the latter also shares its very name with the monsters. It is The Angel of Grief, also referred to as The Weeping Angel.

William Wetmore Story, The Angel of Grief Weeping Over the Dismantled Altar of Life, 1894, Protestant Cemetery, Rome, Italy. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Built in 1894 by William Wetmore Story for his wife Emelyn’s grave, the sculpture depicts a grief-stricken angel weeping, flung across the tomb.

Both the existing statue and the fictional monsters use the image of an angel covering their eyes. While Story’s work expresses genuine grief, the predatory Weeping Angel’s appearance of sorrow is unnatural, a mask which is ready to fall away and strike the moment you blink…

More darkness. This time, a hidden one. Imagine you’re stuck inside a broken-down Crusader space truck on an airless planet called Midnight. Then someone is knocking, desperate to come in—So begins the plot of one of the darkest Doctor Who episodes ever titled “Midnight.”

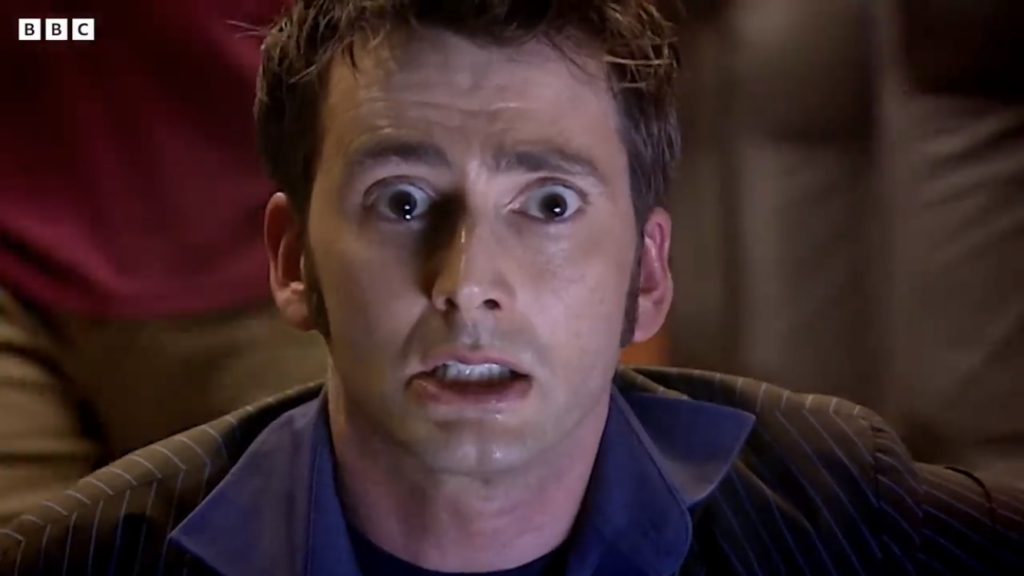

The monstrous threat is invisible. Instead, the audience encounters a claustrophobic bottle episode that examines primal fears, lending uneasy insights into human nature… There’s only so much to say without giving away the whole story. Nevertheless, we can look at one of the most arresting images the episode gives us of the Doctor, wide-eyed and paralyzed in fear. This is, arguably, as helpless as he could be.

Still from Doctor Who, “Midnight”, S4E10. Doctor Who/BBC.

The Doctor, trapped by something he cannot see, feels like a waking nightmare. Such a loss of control conjures up that recurring, ever-changing fear toward the unknown. The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli, a painting of the same name, taps into this hair-raising theme.

Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781, The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI, USA.

This dark painting depicts a woman in the clutches of a bad dream. The leering incubus on her chest and the looming mare’s head at her bedside could denote the terrifying sensation of sleep paralysis. Both symbols are sinister but likely not the true source of fear; the nightmare comes from whatever horrors are unfolding inside the woman’s mind. What we, therefore, cannot see.

In a similar way, Doctor Who exploits this gap in knowledge to terrify us; all we can see is his reaction to the entity in “Midnight,” not the entity itself. It is, perhaps, infinitely worse than sighting a monster in all its horrific glory.

We end almost where we began, “in a wibbly wobbly, time-wimey sort of way,” as the Doctor would say. Like we saw in “Vincent and the Doctor” with a visit to the Musée d’Orsay, a comparable setting is used for the show’s 50th-anniversary special, “The Day of the Doctor,” with the Doctor and companion Clara reunited to look at a mysterious painting held inside the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Still from Doctor Who, “The Day of the Doctor”, S7E14. Doctor Who/BBC.

Titled Gallifrey Falls, the piece displays the fatal Time War that occurred on the planet Gallifrey, the home of the Time Lords.

The theme of a once-great civilization crumbling is a recurring one in art. The vivid reds and ambers in the fires on Gallifrey hauntingly resemble portrayals of the Fall of the Roman Empire in art.

Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire, Destruction, 1836, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Like Gallifrey Falls, Cole’s work encapsulates a moment in history, namely the Fall of Rome. Both pieces have an undeniably somber tone. And yet, maybe due to the very fact that they’re showing a world in the midst of falling rather than an aftermath bleak and bare, there is hope that the tales of Rome and Gallifrey might live on.

Just like the regenerating character of the Doctor, works of art can ensure people and places persevere beyond countless lifetimes. And though there is endless wonder in the thought of an alien Time Lord with two hearts, the enchantment it creates is, deep down, very human. Here’s to the next ten years, Doctor Who—may you visit the world of art again and again!

Amanda Clegg: Madame de Pompadour portrait in oils for Doctor Who. Accessed 23 Nov 2023.

Steven Moffat: ‘Blink’, S3E10, Doctor Who. Accessed 23 Nov 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!