Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Art Nouveau, the movement that flourished between 1890 and 1910, developed at the apex of Belle Époque, the period which encouraged modernity and artistic breakthroughs more than any other, as a reaction against the strict academicism in art of the early 19th century. Much like the Arts and Crafts movement, Art Nouveau sought to deconstruct traditional ideas around hierarchy in art and to equate what was considered “fine art” (painting and sculpture) to the “decorative arts” (furniture-making, jewelry, miniature sculpting, tapestry, embroidery, etc.). The movement was also inspired by the freshness and fluidity of nature. What is little known about Art Nouveau is the large contributions that female artists made to the movement.

Art Nouveau’s primary stylistic characteristics include intricate floral patterns, fresh geometric motifs with curves rather than strict lines, and of course, highly idealized female figures. However, the women involved with Art Nouveau, much like the women involved with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, served not only as muses but as artists too.

The movement is characterized by enthusiasm for the decorative arts and graphic design. This increased the esteem that applied arts, a traditionally female-dominated field, held by the general public, and thereby elevating women as artists too. Therefore it is important to learn more about the female artists who defined the Art Nouveau movement and celebrate them.

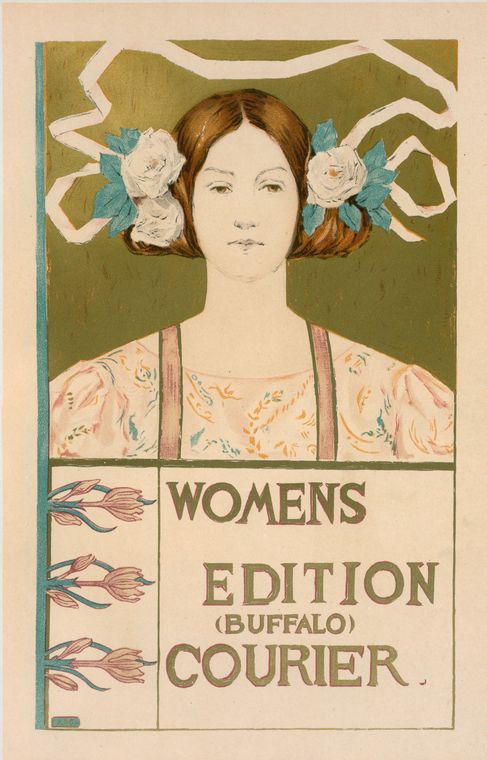

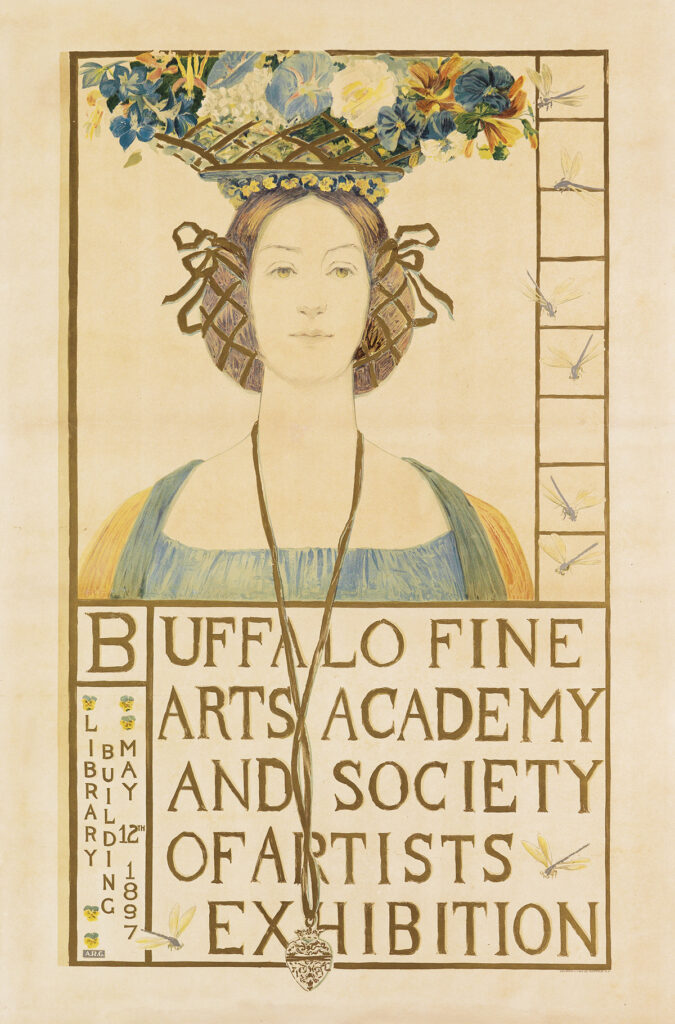

Alice Russell Glenny (1858–1924) was an American graphic artist who was most renowned for her Art Nouveau posters. She was an outstanding figure in the arts in her hometown of Buffalo, New York.

Glenny was an active proponent for the interests of American women artists. She designed the iconic cover below for the magazine Buffalo Courier: Women’s Edition. Her work shows a woman with a Japanese-inspired hairstyle and a stern face looking away from the viewer. The color palette of the woman is pale and contrasts with the olive-green background. This, along with the fact that the ribbons form the shape of a Doric order column, creates a sense of classical revival. Her features are feminine, as are her hair and clothing, but the model maintains her staunch position on the issue of women’s rights.

Glenny made different variations of that poster for different audiences. Those different versions further prove the artist’s intention to blend high, classical art with modern pursuits. The reference Glenny makes to Grecian art is more overt, and her insistence on establishing rights for female artists ever clearer.

The artist’s fame overtook the city of Buffalo. Almost 150 years after her birth the tome American Women: A Library of Congress Guide for the Study of Women’s History and Culture in the United States included Alice Russel Glenny as a trailblazing graphic artist.

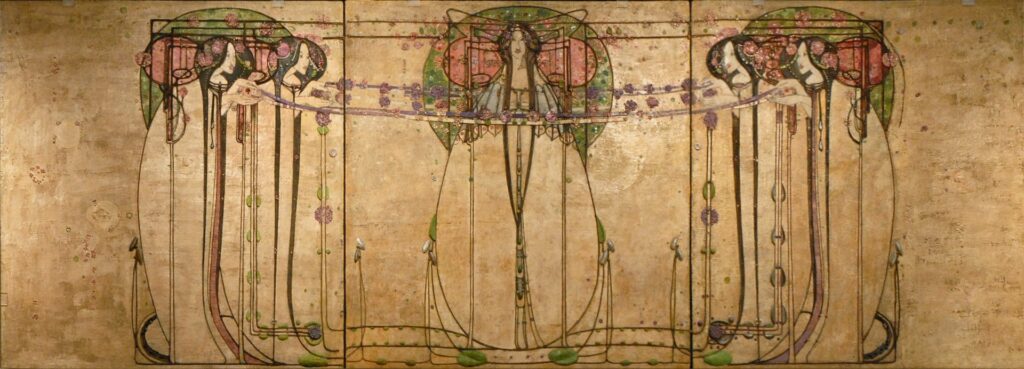

Margaret Macdonald (1864–1933) was a Scottish artist whose work defined the “Glasgow Style” in the late 19th century. As well, her depictions of ethereal figures made a significant impact on the Art Nouveau movement.

After completing their studies at the Glasgow School of Art, together with her sister Frances, the duo opened the Macdonald Sisters Studio in Glasgow. Their oeuvre was largely inspired by Celtic imagery and folklore. Many of Margaret’s works incorporate muted tones, elongated nude forms, and an interplay between geometric and natural motifs. It was those unique characteristics that set her apart from other artists of her time.

Her most renowned work, The May Queen, is a huge panel painting that depicts a central female figure framed by two women on her left and two on her right. The style is reminiscent of Art Nouveau but has some unique elements, for example, the extremely elongated figures and the lack of intense colors.

Her works, along with those of her collaborating sister, defied their contemporaries’ conceptions of art. Thus, the two reached considerable success during their lifetime within European artistic circles. Margaret Macdonald even exhibited at the 1900 Vienna Secession and the influence she had on Gustav Klimt is evident.

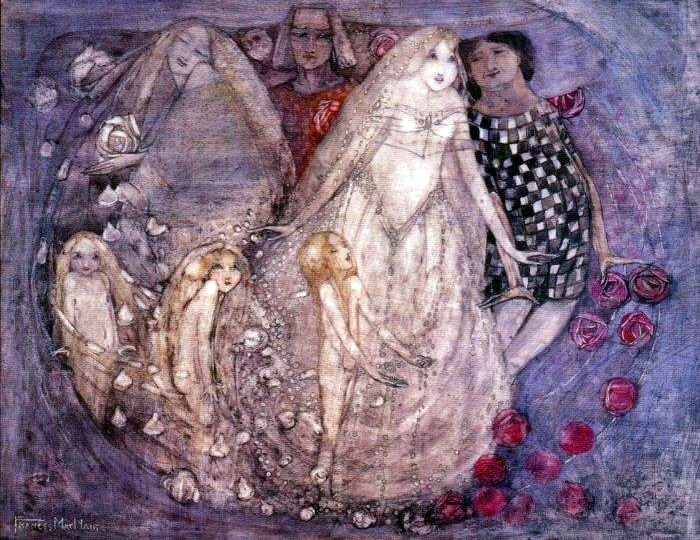

Frances Macdonald (1873–1921), the lesser known of the two Macdonald sisters, was an artistic follower of the Glasgow Style who studied at the Glasgow School of Art.

In the mid-1890s the sisters left the School to set up their independent studio. They collaborated on graphics, textiles, and illustrations. The styles of Margaret and Frances may be similar but they are still distinguishable. Frances seems to be using much bolder colors than her sister and her figures look more human and less static than Margaret’s. Her canvases are full of action and emotional display. Each one tells a different, complicated story. In many ways, Frances’ style is reminiscent of Marc Chagall’s style.

Her works A Choice and A Paradox are exemplary of the complexity of the stories she chose to narrate. Nothing is obvious and we, the viewers, must try to decipher the content and meaning of her works.

Even though the two worked alongside each other (but also individually), Frances is unfortunately significantly less known than her sister. This is because her husband, Herbert McNair, destroyed many of her works after her death. However, both artists portrayed women in ways that ascertained their own emancipation. Their female figures were always the protagonists of their own stories, never the supporting actors.

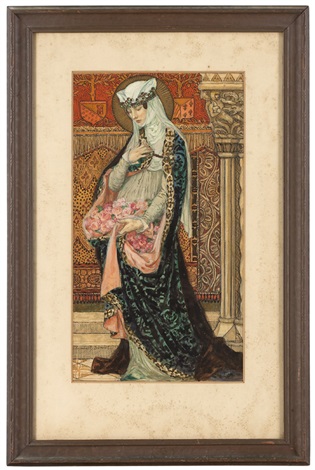

Élisabeth Sonrel (1874–1953) was a French painter and illustrator who both influenced and was influenced by Art Nouveau aesthetics. After studying with her artist father, she went on to formally train at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Early on in her artistic career she produced Art Nouveau posters and illustrations, but her style later developed into Pre-Raphaelite after taking a trip to Italy, where she became enamored with Sandro Botticelli’s style.

.jpg)

She depicted almost exclusively female figures and her favorite subject matter included Arthurian romances, biblical themes, and mythological scenes. Her artistic style is an alluring, unique mix of the Art Nouveau and Pre-Raphaelite styles.

Sonrel also participated at the Exposition Universelle of 1900, a year in which the theme was Art Nouveau. Her work was highly successful, receiving accolades and medals and selling for 3,000 francs. The artist remained highly prolific during her lifetime and kept working until around the time she was 70.

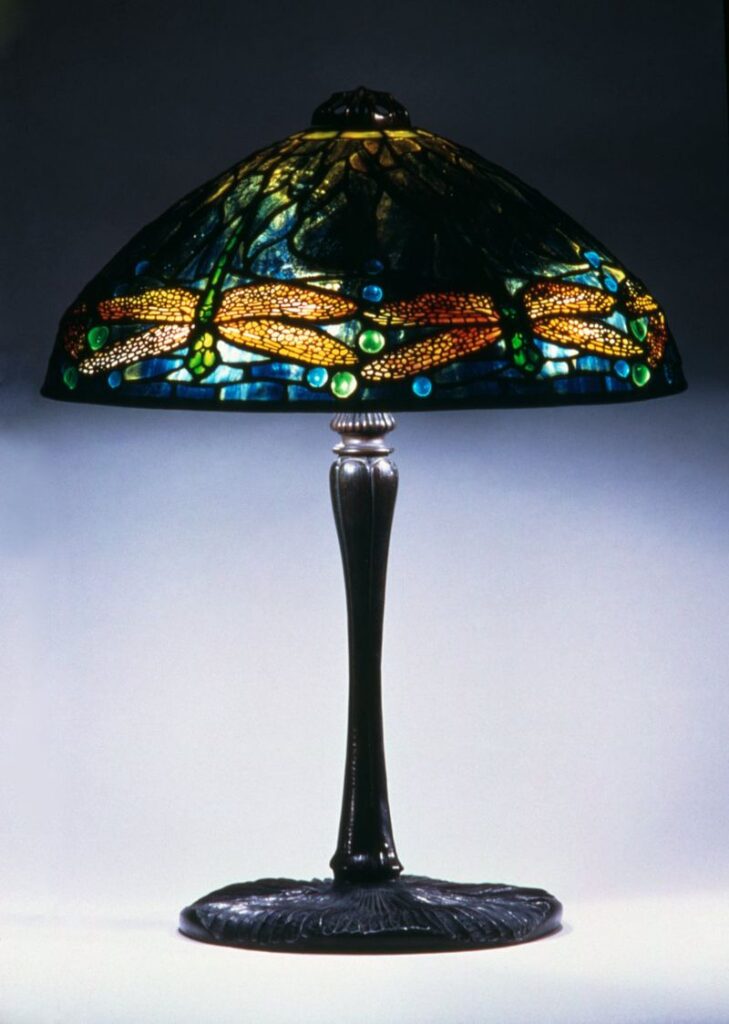

Clara Driscoll (1861-1944) was an American designer who served as the Head of the Department of Women’s Glass Cutting for Tiffany Studios in New York City. She was said to have been one of the highest-paid women of her time, making around $10,000 per year.

In her 20-year tenure at the company, she designed over thirty iconic Tiffany lamps. Inspired partly by Art Nouveau and partly by the Arts and Crafts movement, her first-ever design was the “Daffodil”. Her Tiffany lamps bore intricate natural motifs of flowers and insects. Eventually, they became symbols of the American tradition in decorative arts.

For most of 20th century though, Driscoll’s male colleagues received credit for designing and creating these lamps. In 2006, scholars Martin Eidelberg, Nina Gray, and Margaret Hofer discovered that it was in fact Driscoll and her female co-workers, the “Tiffany Girls”, who designed and brought to life the masterpieces known as Tiffany Lamps.

A New York Times writer noted in his exhibition review on the “Tiffany Girls”, hosted at the New York Historical Society:

(…) as the exhibition was being installed, some of these little metal silhouettes used to make a gorgeous daffodil lamp shade were still jumbled in a box on a storage table. Meaningless on their own, when put in order they bring to life an exquisite object, just as the show itself, a puzzle now assembled, illuminates the talented women who had long stood in the shadow of a celebrated man.

Jeffrey Kastner, Out of Tiffany’s Shadow, a Woman of Light, 2007, The New York Times.

All these female artists came from different backgrounds, countries, and disciplines. In spite of that, they all managed to make immeasurable contributions to the Art Nouveau style and movement. Alice Russel Glenny, Margaret and Frances Macdonald, Élisabeth Sonrel, and Clara Driscoll were artists at a time when the appropriate thing for a woman to do was pose, not create. These women, among others, are also proof that there is much more to Art Nouveau than Alphonse Mucha.

Eidelberg, Martin, Nina Gray, and Margaret Hofer. A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls, New York Historical Society, 2007.

Green, Cynthia, “The Scottish Sisters Who Pioneered Art Nouveau”, JSTOR Daily, 19 December 2017. Accessed 18 Jul 2020.

Kastner, Jeffrey, “Out of Tiffany’s Shadow, A Woman of Light”, The New York Times, 25 February 2007. Accessed 18 Jul 2020.

King, Julia, The Flowering of Art Nouveau Graphics, 1990, p. 123.

Smith Galer, Sophia, “Ten female artists you should know about”, BBC, 2 November 2017. Accessed 18 Jul 2020.

“Women in Art Nouveau”, Europeana. Accessed 18 Jul 2020.

“Women in Art Nouveau”, Google Arts and Culture. Accessed 18 Jul 2020.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!