Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

Johannes Vermeer is an enigmatic figure in the history of art. He is considered one of the most famous artists of the Dutch Golden Age. Why are his quiet interior scenes so captivating? Is it perhaps the dexterous way Vermeer uses light to play over the different surfaces? Or perhaps it is the silent mystery in his compositions that forces the viewer to guess its untold story? Whatever the reason, Vermeer continues to captivate modern viewers with his small luminous images. One of his masterpieces, Art of Painting, explores many of the techniques that shape that Vermeer’s signature style.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

The Dutch Golden Age (1588-1672) was an exciting time for artists. It was a time and place marked by prosperity, stability, and commerce. The domestic art market was booming with insatiable market demand and with an incredible market supply. Artists were painting and customers were buying. However, despite this economically supportive atmosphere for artists, Johannes Vermeer did not become a full-time artist. He was primarily an art dealer and an innkeeper, and therefore only painted 35 known works of art. In comparison to his contemporaries, Vermeer’s œuvre is tiny. However what he lacks in quantity he compensates in quality. His Art of Painting clearly proves the quality over quantity mindset.

Johannes Vermeer, Procuress, 1656, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail. Presumed self-portrait.

Art of Painting was painted approximately from 1666 to 1668. It is an oil on canvas measuring 100 cm wide by 120 cm high (39.4 in wide by 47.2 in high). The painting depicts an artist’s studio with the artist sitting at his easel and a model standing further away by an unseen window. The room is opulently furnished with several pieces of furniture, three pieces of fabric, a bronze chandelier, a Dutch Republic map, oak beam rafters, and checkerboard flooring. This interior is not a poor starving artist’s studio. The viewer is witnessing a prosperous artist pursuing his next image.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

The female model is standing in the guise of Clio, the muse of history. According to Greek mythology, Clio would inspire writers to write about historic events in their great epic poems. She was one of the nine muses to live on Mount Parnassus as an attendant to Apollo, the god of art and music. The model is wearing and holding some of Clio’s attributes. The laurel wreath on her head symbolizes victory. The trumpet in her right hand symbolizes fame. Finally, the book in her left hand symbolizes the writing of history which is closely associated with Herodotus (ca 484 – ca 425 BCE), one of the most famous Greek historians.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

In front of the model is the artist. He is viewing her and painting her image on his canvas. Therefore, his face remains unseen to the audience as he presents his back to the foreground. What is deeply interesting is his choice of clothing. He is not wearing the contemporary clothing of a 17th-century Dutchman. Rather he is wearing a style associated with a 15th-century Burgundian. The black outer shirt has artful slits on both the upper back and lower sleeves that reveal a white undershirt. Further adding to the antiquated feeling are the red stockings and puffy white garters on his legs. Many scholars believe Vermeer is representing the artist in the guise of the history of painting. Vermeer is presenting a 15th-century Burgundian artist depicting Clio, the muse of history. Art and history are fusing together. The audience is viewing an allegory of art history.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

Behind the artist and his muse is a grand map of the Dutch Republic. It displays the 17 provinces in the center with vignettes of important cities and monuments in flanking columns on the left and right sides. Such a map was a very common adornment in contemporary 17th-century Dutch homes. However, Vermeer includes it in this painting to proclaim the Dutch Republic as the new inheritor of the Western art tradition. It is the land of art.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

Laying on a table beside the model is an assortment of objects. The most prominent is a white plaster death mask. During the 17th century, it was common for plaster models to be made from the faces of recently deceased famous people such as royalty, artists, and celebrity-criminals. They stood as physiognomic records, historic artifacts, and curiosity pieces. The inclusion of a death mask in the Art of Painting may imply the woeful end to the unfinished canvas in the scene. The painting may not be a great success. Perhaps it will be too mediocre? Or, the mask may be a memento mori, reminding the viewer that everything and everyone has a lifecycle with a definite ending?

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

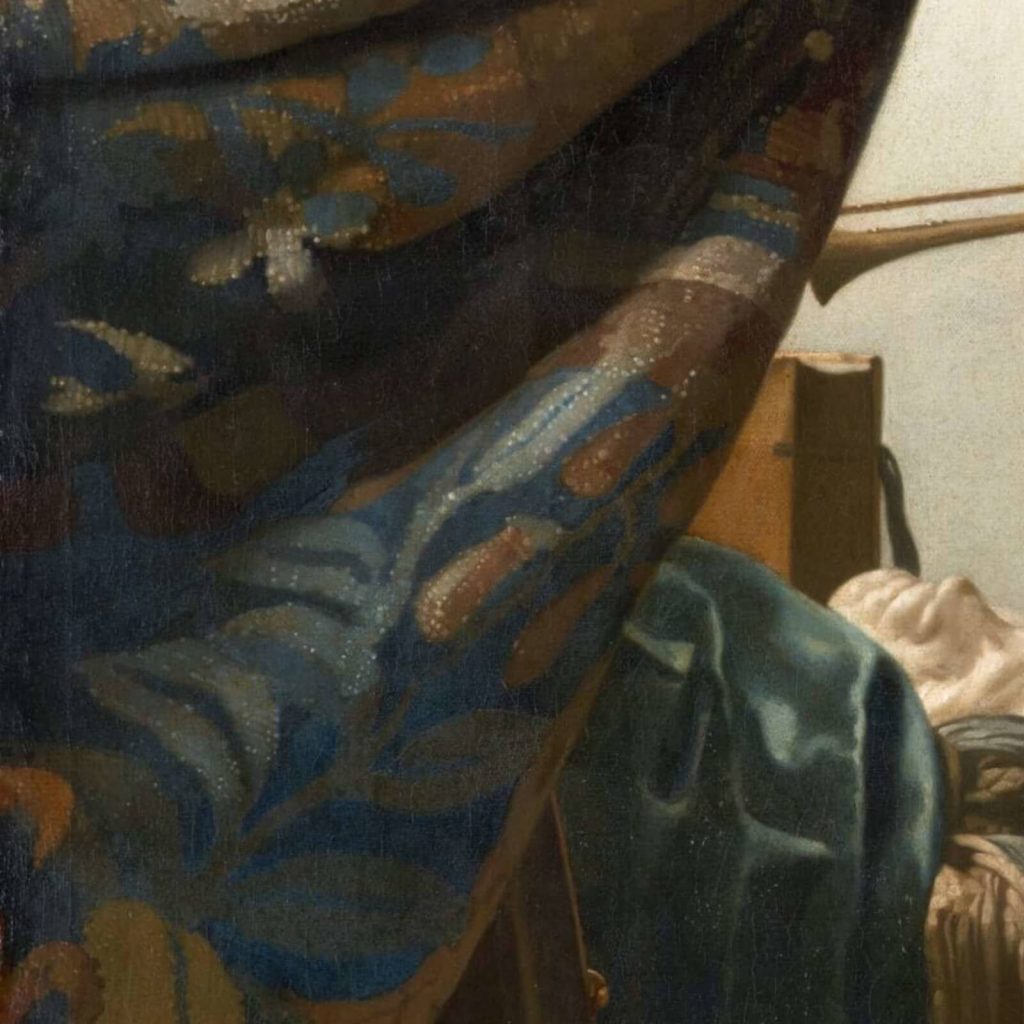

As the viewer shifts focus toward the foreground, it becomes apparent that there is a large curtain enveloping the left border of the scene. It is dramatically swept upwards in a typically Baroque swag motif. This motif implies the artificial construction of the presented scene. Like a theater production, the image of the muse, artist, and their surrounding scenery is presented from behind a curtain. A secret moment is dramatically revealed with the side sweep of the concealing curtain. This Baroque motif implies the viewer is an outsider and almost a voyeur admiring a clandestine composition.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

What is charming is the addition of the chair at the base of the curtain. It speaks to the viewer to take a seat and admire this artificially constructed moment. The curtain repels, but the chair invites. A paradox of push and pull plays on the painting’s left edge.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

Art of Painting is a visually busy painting that has more material objects than many of Vermeer’s other paintings. It is almost a catalog of Vermeer’s skills in depicting cloth, paper, metal, stone, and wood in different light conditions. The Art of Painting could be argued to be like a modern business card showcasing Vermeer’s wide dexterity. Everything is illuminated or shadowed by the light of artistic inspiration emanating from the unseen divine source. Everything in the scene is calm, quiet, and beautifully rendered in precise realism.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

It is interesting to note that when Vermeer died, Art of Painting was one of the few paintings kept by his wife, Catharina Bolnes, during the liquidation of his artwork. Perhaps Catharina Bolnes felt this painting represented the culmination of her beloved husband’s career. Perhaps it was a summary of his life’s endeavor to master painting. Whatever the reason, Art of Painting is a Vermeer masterpiece. It is an example of mindfulness where everything speaks of still meditation. We are forced to pause and reflect. Perhaps Vermeer sought serenity in his studio away from the bustle of everyday life. Even geniuses need alone time.

Johannes Vermeer, Art of Painting, ca. 1666-68, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Detail.

10,000 Years of Art. London, UK: Phaidon Press Limited, 2009.

“Art of Painting.” Collection. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

Bischoff, Cäcilia. Masterpieces of the Picture Gallery. Vienna, Austria: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 2010.

Charles, Victoria, Joseph Manca, Megan McShane, and Donald Wigal. 1000 Paintings of Genius. New York, NY, USA: Barnes & Noble Books, 2006.

Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Lodwick, Marcus. Museum Companion: Understanding Western Art. New York, NY, USA: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003.

“Procuress.” Collection. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!