April 1, 1939 marked not only the end of the Spanish Civil War but also the fall of the Second Spanish Republic. The victory of General Francisco Franco’s rebel forces resulted in the overthrow of Spain’s leftist Republican government and its subsequent replacement with a Nationalist dictatorship that would last until Franco’s death in 1975.

Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Spanish Civil War

Today, 80 years after the end of the conflict, the legacy of both the Second Spanish Republic and the Franco regime continue to be controversial subjects of political debate. What remains clear, however, is that the three years of civil war had a profound impact on the country’s cultural sphere, as the most prominent artists of the day used their talents and means of expression to react to what was happening around them.

The Spanish Civil War is particularly noteworthy for the international impact that it had, especially in artistic and literary circles. George Orwell’s experience fighting for the P.O.U.M., one of several pro-Republican militias, is recorded in his memoir Homage to Catalonia, while Ernest Hemingway’s work as a foreign journalist during the war served as an inspiration for his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. Jean-Paul Sartre’s short story The Wall is an existentialist account of the condemnation and execution of prisoners by Nationalist soldiers, which was the tragic fate the poet Federico García Lorca, among many others. In Spain, the most prominent artists of the modernist avant-garde were mobilized to react—some producing overt political propaganda posters and others expressing their views through more abstract works.

Republican Versus Nationalist Propaganda

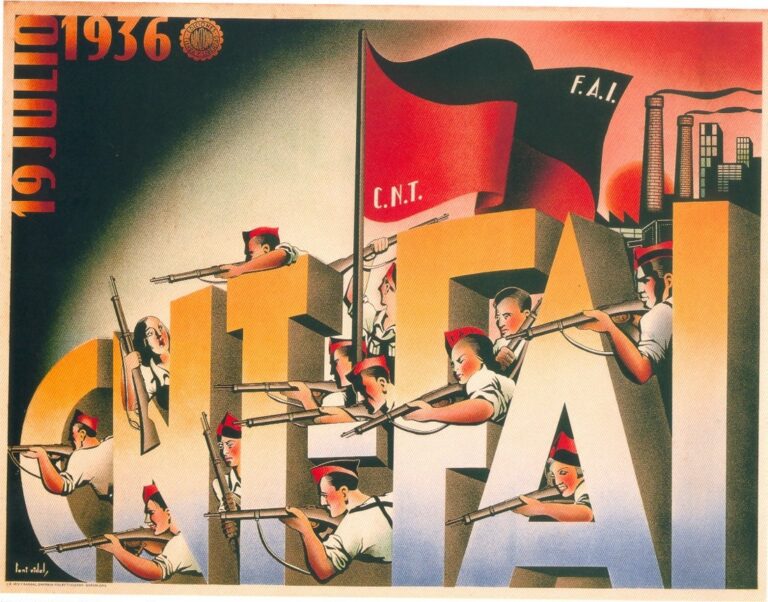

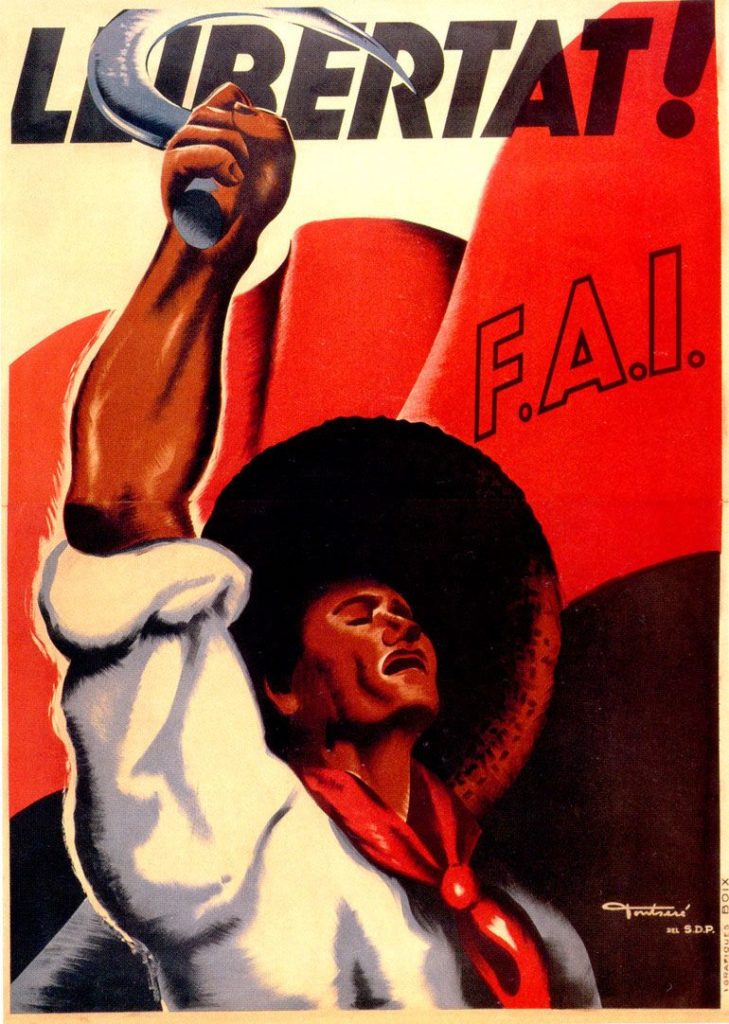

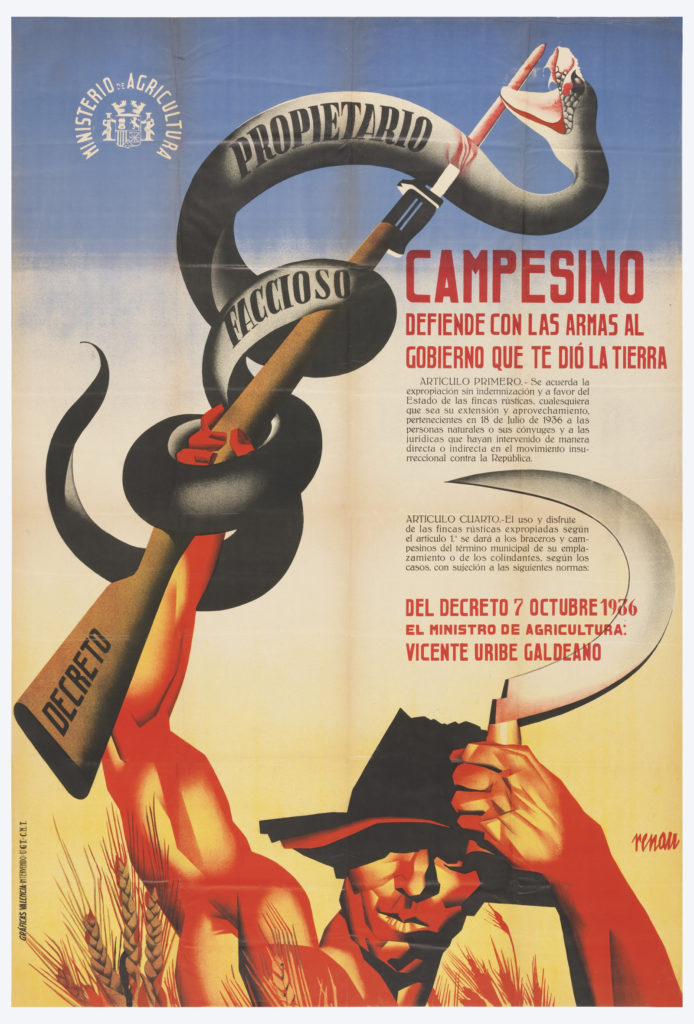

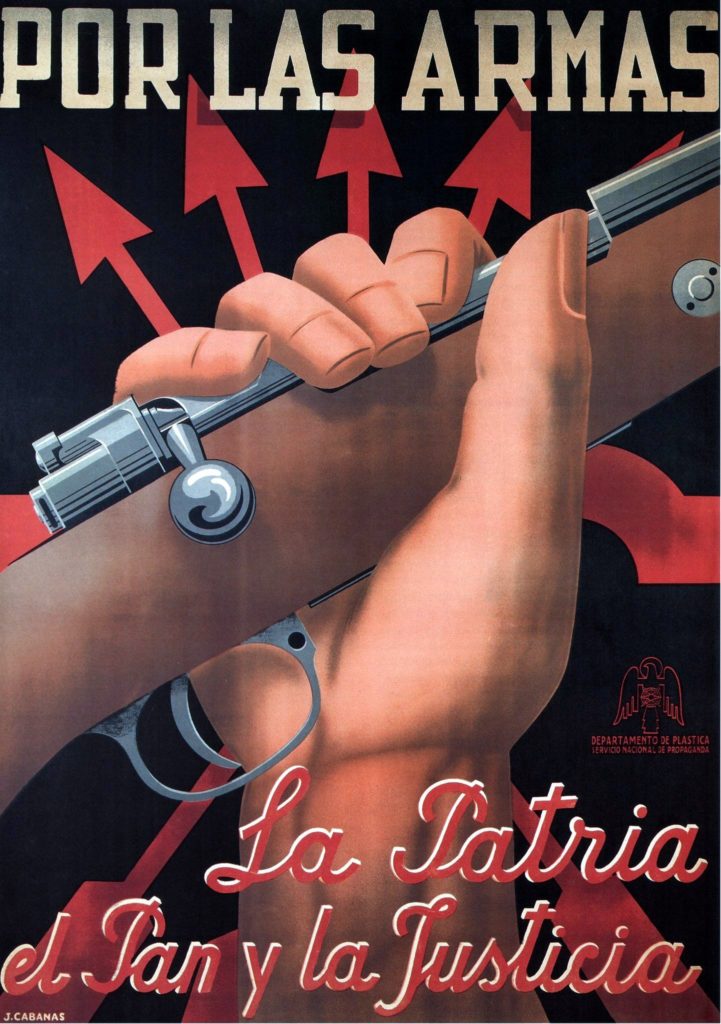

Political propaganda posters have become an icon of the civil war era, as both Republican and Nationalist forces employed artists to rally support throughout the duration of the conflict. Most Republican posters were produced in the socialist realist style, which had already become the official artistic form in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. Common themes included idealized depictions of peasants or proletarian workers, socialist symbolism, as well as official communiques from the government or allied militias. Indeed, Nationalist propaganda shared many of the same artistic qualities, except that the extremely traditionalist or patriotic slogans and fascist imagery made it more akin to the realism that was characteristic of political posters in Nazi Germany.

Many Republican poster artists came from Barcelona, as the Catalan region had a long tradition of revolutionary thought and served as a Republican stronghold throughout the war. Among them, Carles Fontserè was one of the most prolific and influential. His poster Llibertat! (Catalan for “liberty”) depicts a peasant wearing a red neckerchief, with his right hand clenched in a fist and wielding a sickle. Behind him waves the red-and-black flag of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (F.A.I.), which together with the National Confederation of Labor (C.N.T.) formed the backbone of Spain’s anarcho-syndicalist movement that stood loyally behind the Republican army during the war.

Shortly after the outbreak of the war, the Ministry of Agriculture passed a decree by which all the land that belonged to supporters of the military rebellion would be turned over to the country’s peasants. This way, nearly a third of the country’s arable land was redistributed to some 300,000 peasants, creating even deeper divisions in an already split society. To spread news of the reform, the Valencian artist Josep Renau created a poster whose heading read Peasant: Defend with Weapons the Government that Has Given You the Land. Like Fontserè’s Llibertat!, Renau’s poster also features a peasant wielding a sickle, but in his raised right hand he also holds a rifle. The butt of the rifle features the word “decree”, while the weapon’s bayonet pierces through the heart of a snake. The snake, here labeled the “factious landlord”, was a commonly used symbol to depict what were seen as the evil and treacherous forces of the Nationalist rebels.

While most of the political propaganda posters produced during the war were in support of the Republican government, the Nationalist rebels also made an effort to gain popular support. As if alluding to the works of Fontserè and Renau, Juan Cabanas’ call to arms similarly featured a raised fist clenching a rifle, with the slogan To Arms: Country, Bread and Justice serving to help legitimize the Nationalist cause. Nevertheless, many differences stand out. The bright colors commonly seen in left-wing propaganda have been replaced with the predominance of black and brown, although the powerful presence of red remains. The main symbolism here is the incorporation of the yoke and arrows in the background, which Franco adopted from the heraldic badge of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, the so-called “Catholic Monarchs” who reconquered Spain from Muslim rule at the end of the 15th century. Also noteworthy is the seal of the Department of Visual Arts – National Service of Propaganda, which featured an eagle that served as a prototype for what would become the country’s coat of arms after the Nationalist victory.

The Reaction of the Avant-Garde

While some artists became directly involved in the production of political propaganda, others chose to pursue more abstract and innovative ways of depicting the turmoil of the civil war era. The most prominent of Spain’s surrealist and cubist painters utilized their signature techniques either to actively take a stance or simply allude to what was happening around them. Whichever the case, the civil war had a great impact on the artwork created during this time.

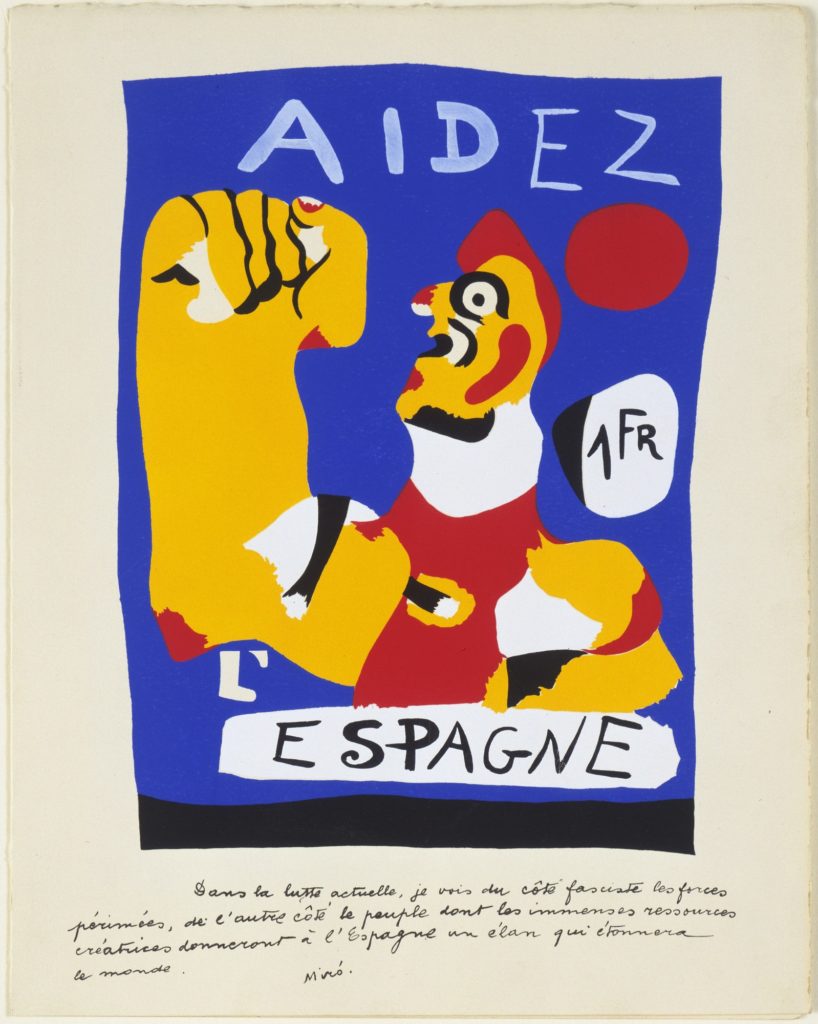

Though he had never mixed art and politics in the early stages of his career, the thematic focus of Joan Miró’s work took a decisively activist turn after he was invited to participate in the International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life, held in Paris in 1937. Together with Pablo Picasso and Renau, Miró saw the event as an opportunity to spread international awareness about the plight of the Spanish Republic. Originally intended to be a postage stamp, Aidez l’Espagne (French for “Help Spain”) ultimately took the form of a poster inspired by the political propaganda that was being circulated around the cities and towns of Spain. In it, Miró depicts the common theme of a peasant with a clenched fist, although he abandons realistic representation and incorporates the flat, bright colors that were characteristic of his style. Underneath the image, he writes: “In the present struggle I see, on the Fascist side, spent forces; on the opposite side, the people, whose boundless creative will gives Spain an impetus which will astonish the world.”

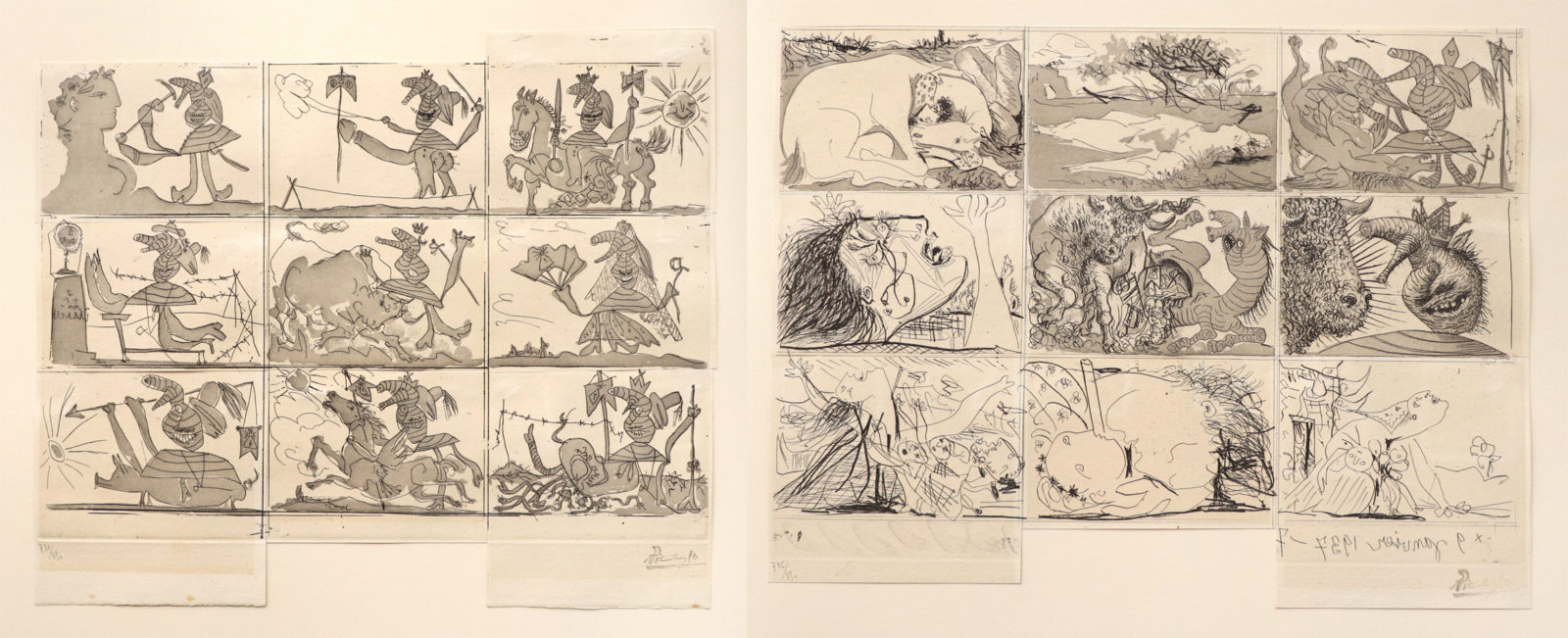

Like Miró, Picasso had refrained from creating political art until the Paris Exposition of 1937. The two sheets of The Dream and Lie of Franco contain nine individual prints that were originally meant to be sold as postcards to raise funds in support of the Republican government. This plan, however, was never realized, and the work was finally assembled with an accompanying prose poem as a satirical critique of Franco. For example, the first image of the first sheet shows the general destroying a classical sculpture with a pickaxe, while the subsequent one depicts him with an exaggeratedly large penis, waving a sword and a flag. Though the work largely disappeared into obscurity after the civil war, it is notable for containing studies that were later incorporated into what would become the artist’s masterpiece: Guernica.

On April 26, 1937, German and Italian war planes executed a bombing raid over the Basque town of Guernica, an operation that gave the Nationalists a significant advantage on the northern front. While the exact death toll of the bombing remains disputed, civilian casualties certainly numbered in the hundreds, and the Basque government has even claimed that over 1,600 were killed in the attack. The horrific massacre served as the inspiration for Picasso’s Guernica, a massive work that stands at 3.49 meters tall and 7.76 meters long. After its completion, the work was first displayed at the Paris Exposition and later exhibited at other venues around the world to raise funds for the Republican cause. Today, a full-size copy of the work hangs at the entrance to the Security Council at the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City to remind world leaders that the destruction and suffering of war is seldom limited to soldiers on the battlefield.

Unlike Miró and Picasso, Salvador Dalí never took a definitive stance during the war. At various times in his life, he manifested support for both communist and fascist ideals, frequently shifting from one extreme to the other. His refusal to explicitly renounce his Nationalist leanings sparked considerable criticism among his contemporaries, the most vocal of whom was George Orwell, who later wrote in an essay that “one ought to be able to hold in one’s head simultaneously the two facts that Dalí is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being”. Like his political views, Dalí’s artwork was equally ambiguous. His prophetic Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War), created shortly before the eruption of the conflict, depicts a tortured body tearing itself apart in a barren wasteland. While it can be assumed that the body is an allusion to the state of the Spanish Republic at that time, the significance of the boiled beans, much like the artist’s true beliefs and sympathies, can only be speculated by the viewer.

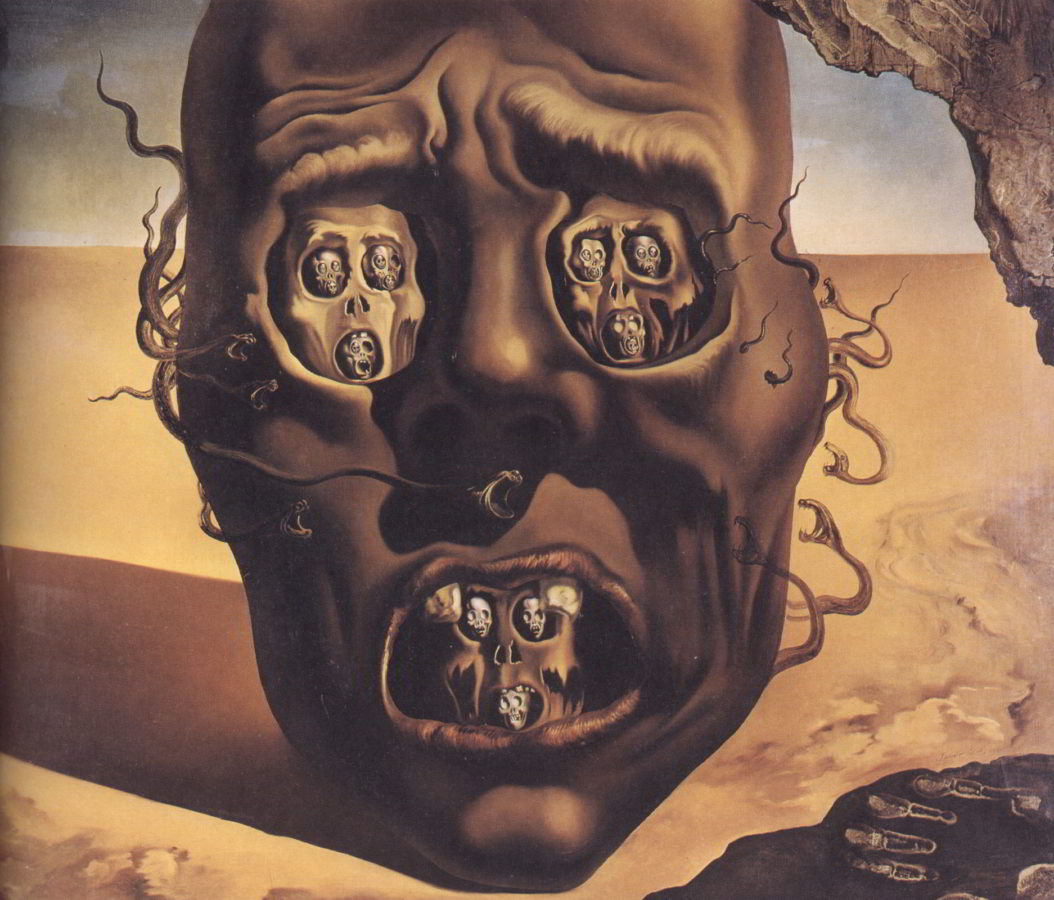

Upon returning from France after the Nationalists had declared victory in 1939, Dalí found that his home had been destroyed and that his sister had been imprisoned and tortured by Franco’s soldiers. As another catastrophic war was looming in Europe, Dalí fled to the United States, where he painted The Face of War, placing his own handprint in the painting’s lower right corner. Following the Republican interpretation of snakes as a symbol of Nationalist treachery, one could interpret this work as implicitly blaming Franco for the devastation of Spain during the civil war. Nevertheless, after the end of the Second World War, Dalí returned to Franco’s Spain and, later in his life, even met with the general to paint a portrait of his granddaughter.

Art as a Reminder of the Past

General Franco died on November 20, 1975, a date that marked the beginning of Spain’s return to democratic rule. In April 2019, the same month that the country commemorates the end of what was the bloodiest and most divisive period in its modern history, the Spanish people go to the polls to participate in what will be their 14th general election since the democratic transition. Unfortunately, however, the deep divisions left by the civil war can still be felt, as the resurgence of regional separatist sentiments and the rise of radical parties on both sides of the political spectrum have come to show. Perhaps for this reason, if for none other, it might do good to return to the art of the Spanish Civil War, for it serves as a stark reminder of what can happen when neighbors turn on neighbors and friends turn into foes.

Learn more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0826521797″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/51TajusopwL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”77″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0521174708″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/41Owu56bPL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”73″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0691157413″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/61qomR1F7zL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”77″]