5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

Since ancient times, patrons have played a vital role in art history. Patronage can be found almost everywhere – in Europe, feudal Japan, and Southeast Asia. In fact, anywhere a royal either imperial or aristocratic system dominates society, we find art patrons.

If an artist could find a wealthy patron, they could find employment for years, as well as have an endless supply of expensive art materials, and possibly even a roof over their head.

The most well-known of the patronage systems is from the Renaissance period. At this point in art history, artists generally worked exclusively at the behest of the rich and powerful. People like the Medici family housed artists in their lavish estates, painting portraits and frescoes. The heady mix of the Medici family and Michelangelo, or the Sforza family and Da Vinci produced some of the most important and lasting works of the era.

But this traditional artist-patron relationship began to change in the mid to late 19th century. Artists who won awards or accolades at their national Academy were still well placed to receive important commissions from wealthy patrons. However, those institutions were traditionalist – valuing religious, historical and portrait-themed paintings. This discouraged any new, unusual or unorthodox work.

In Paris, for instance, Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir rebelled against the rigid traditions of the French Academy. After repeated rejections by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, they started their own art show called Salon des Refusé, or the Salon of the Rejected. The works displayed at that salon sowed the first seeds of the world-changing Impressionism movement.

However, without a patron, who pays the bills? Remember the story of Vincent van Gogh. Prolific and immensely talented, he never found commercial success in his lifetime. Today his work fetches millions, but he died a pauper.

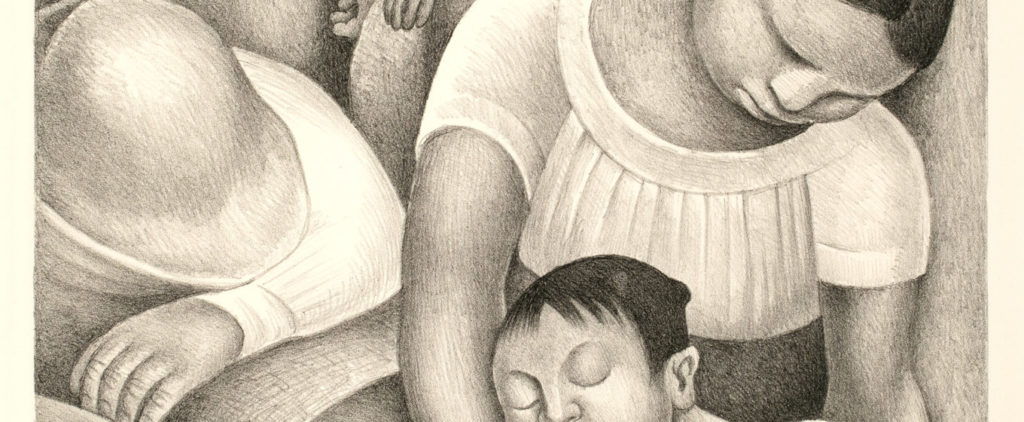

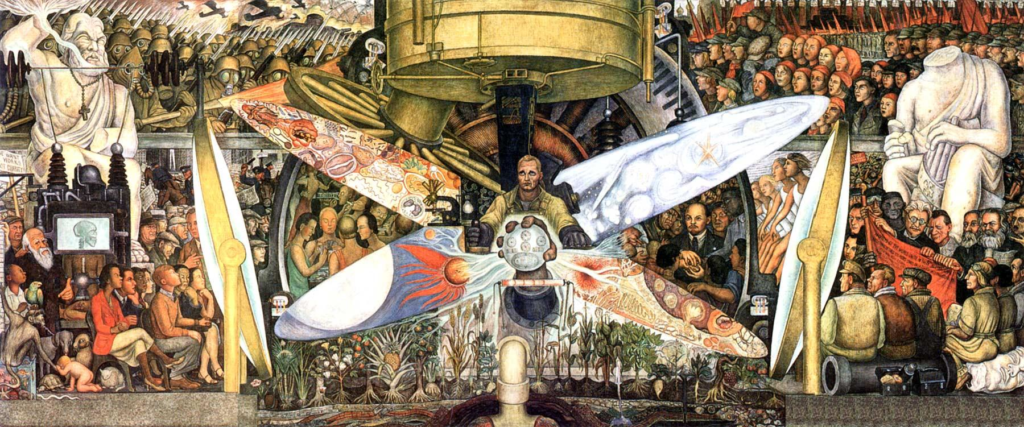

But the relationship between artist and patron doesn’t always run smoothly. In 1932 wealthy US industrialist John D. Rockefeller Jr. commissioned Mexican artist Diego Rivera to paint a mural inside Manhattan’s Rockefeller Centre. Rockefeller was of course aware of Rivera’s radical, left-leaning politics, so they agreed the scene to be painted in advance.

The contract specified that Man at the Crossroads should show someone looking with uncertainty but hope toward a new and better future. However, at the last minute; Rivera altered his design. Instead, the mural was filled with hundreds of characters illustrating the dominant political ideologies of the time. Perhaps the most problematic part was the inclusion of Vladimir Lenin. It is rumored he also depicted Rockefeller himself sipping martinis with a prostitute.

The Rockefellers asked Rivera to redo the mural, but the artist declared that he’d rather see the work destroyed than mutilated. So that is exactly what Rockefeller did – Rivera was paid, dismissed, and the mural was covered up and later chiseled off. A year later, in 1934, Rivera made a new version entitled Man, Controller of the Universe which is still on display in Mexico City.

Including a patron in a scene is nothing new of course. A conventional, deferential gesture to a patron has always been to include a likeness of them within a painting. In Medieval art patrons and donors were frequently tucked into the religious or historical paintings or altarpieces they commissioned. By the 15th century, painters were depicting their donors with very distinctive, recognizable features. See the man and woman in the left wing of the Annunciation Triptych below.

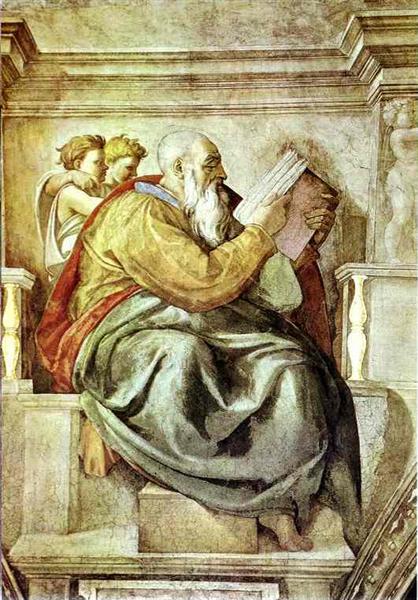

However, when Michelangelo painted the face of Pope Julius II onto the body of the prophet Zechariah, it wasn’t quite as generous as it seemed. Pope Julius was openly referred to as Il Papa Terrible, and in the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo made a pointed reference to the corruption rife within the church. At the east entrance to the Sistine Chapel, we see Zechariah reading a book as two young angels peer over his shoulder. Some scholars have pointed out that one figure offers a hand gesture then called “the fig”. With the thumb stuck between the index and middle fingers, this symbol apparently meant “f*** you.”

Amazingly, the artist got away with this, and continued to push his luck when he was invited back to paint The Last Judgement 30 years later – he painted the gaping mouth of hell on the wall directly behind the altar – possibly as a warning that even the highest in the church will face final judgment.

Fast forward to more recent times, and British ceramicist Grayson Perry also responded to a falling out with a patron in a rather amusing way. He exhibited a pair of large black pottery penises which he entitled Portrait of Anthony d’Offay!

Modern patrons may not require their artists to build their fame and reputation and secure their place in history. But just like the patrons of old, when the relationship works, artists are offered a pathway to success and economic stability. Let’s end with two patrons who had incredible success cultivating emerging talent.

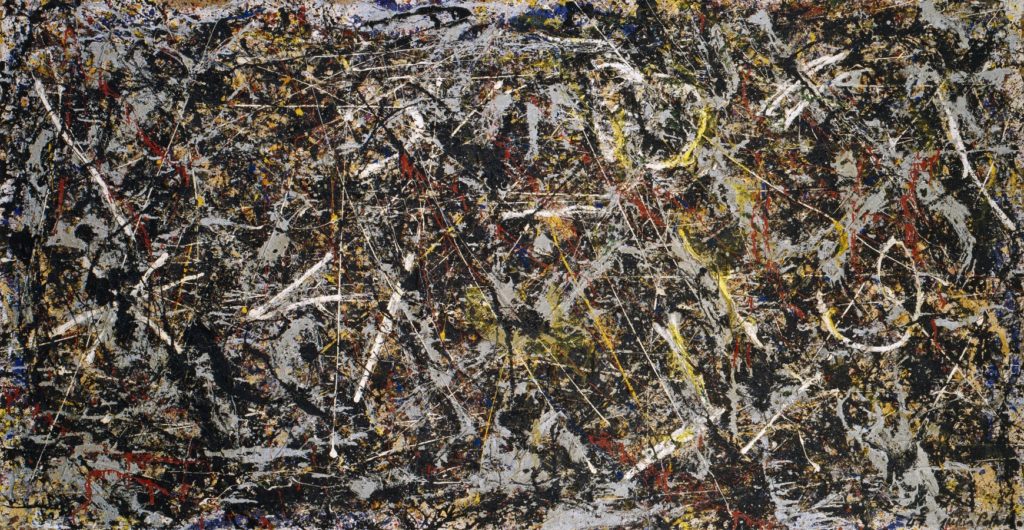

Peggy Guggenheim was a monumental patron within the American art world. It is said that she gave more first showings to new artists than any other patron in the US. She included Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock in her stable of artists.

On this side of the pond, Charles Saatchi is possibly one of the most divisive figures in British contemporary art, but there is no denying his influence. Art critic Matthew Collings calls him the ‘nuclear energy’ of British collectors, and that without him many young artists would be broke. Saatchi began collecting in 1969 and opened his first gallery in 1985. He is best known for his connection with the YBA (Young British Artists), including Tracey Emin, Gavin Turk, and Damien Hirst. In 2010 Saatchi donated his gallery, with art worth millions of pounds, to the British public. It is now the Museum of Contemporary Art for London, and it provides a launching pad for young artists, many of whom go on to successful global careers.

We will however give the final word on patrons to Mr Thomas Gainsborough, who damned his wealthy portrait subjects, saying that:

‘They have but one part worth looking at, and that is their purse!’

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!