Diana in Art: Goddess of the Hunt

As the Roman goddess of hunting, the moon, and nature, it is unsurprising that Diana is often depicted among animals and nature in art. Throughout...

Anna Ingram 8 September 2025

From dancing colors to a kinetic steel monument, discover the lives and works of five influential and international modern artists – each of whom was born in towns of today’s Ukraine at the turn of the 20th century.

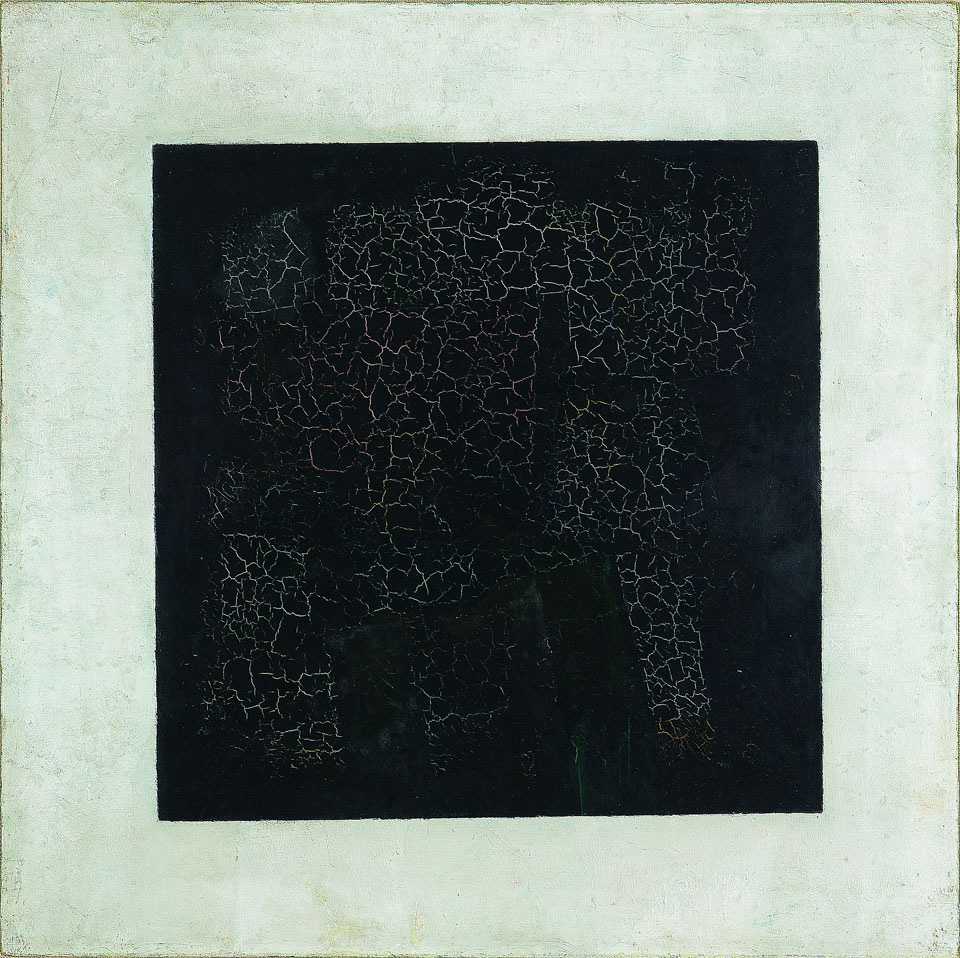

Kazimir Malevich, Black Square, 1913, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

In 1913, Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) changed the course of art history by making a painting without a figurative subject. As a result, he is remembered as one of the critical figures of abstraction. This bold new approach to painting quickly dominated modern art.

Born in Kyiv Governorate in then Russian Empire (today’s Ukraine) to a Polish family, Malevich was always captivated by the spiritual nature of simple shapes. He invented an art movement called Suprematism, which aimed to deconstruct a painting’s subject down to its most basic components.

Black Square demonstrated the straightforward power and potential of abstract art. Interestingly, Malevich first displayed the painting in a manner traditionally reserved for religious icons. Albeit controversial, this emphasized the artist’s personal spirituality.

Malevich and his followers didn’t take long to abandon painting real-life subjects completely. Regarding Black Square, the artist later wrote,

Trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.

Sonia Delaunay, Electric Prisms, 1914, Musée National D’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. Museum’s Website.

In collaboration with her husband Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) created a new art movement called Orphism. Like other Orphists, she used dramatic colors and dynamic shapes to create patterns inspired by the properties of light and sound.

Delaunay was born in Odesa, Ukraine (then Russian Empire), but relocated to Paris in the early 1900s. There, she discovered all things avant-garde, from Cubist painting to modern fashion design. Her resulting body of work is an energetic patchwork of shapes and colors that evoke a sense of movement.

Sonia Delaunay’s vibrant paintings and eccentric fashion designs popularized the aesthetic of geometric abstraction in modern art. By the 1960s, she became the first living woman artist to have a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre.

Louise Nevelson, An American Tribute to the British People, 1960-1964, Tate Gallery, London, UK. Museum’s Website.

Ukrainian-American artist Louise Nevelson (1899-1988) emigrated from Pereiaslav then Russian Empire, today’s Ukraine territory, to the United States as a child. Immediately upon arriving, she was captivated by the burgeoning modern art scene she discovered in New York City.

As a young artist, Nevelson gravitated towards wood assemblage sculpture. Like joining pieces of a puzzle, Nevelson combined raw materials and found objects to form massive abstract sculptures. Then, she painted her final pieces—each usually a complex arrangement of nested geometric forms—in monochromatic black or white.

Louise Nevelson’s monumental sculptures asserted the right of women artists to take up space in the art world, both literally and figuratively. She was one of the first women artists to enter the male-dominated realm of installation art.

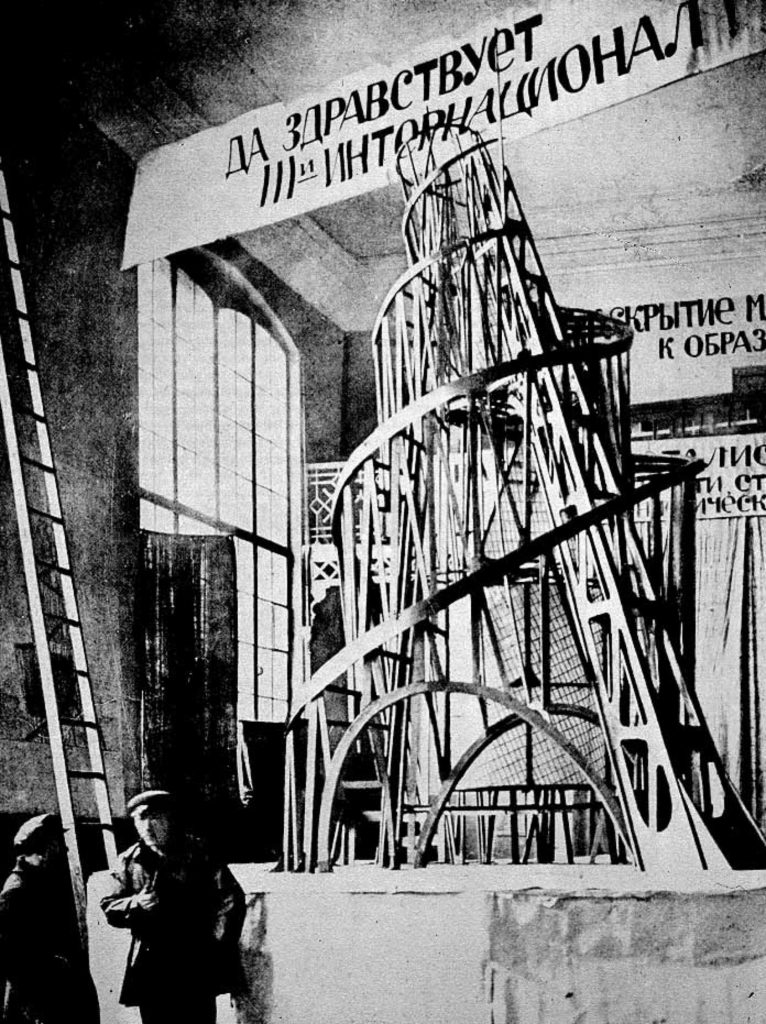

Vladimir Tatlin, Monument to the Third International, 1919 (photograph of the architectural model). Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

A Soviet architect who was brought up in Kharkiv, then Russian Empire, Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) became famous for designing a building that was never actually built. His epic plans for the Monument to the Third International (colloquially known as Tatlin’s Tower) were foundational to Constructivism. This movement favored the industrial assemblage of materials for practical purposes, including propaganda.

Tatlin’s Tower aimed to inspire the proletariat class to rebuild a stronger, and more modern, Soviet Union. It had a projected height of 1300 ft (ca. 396 m) and would use exclusively modern materials like steel and glass.

The monument was also designed to be in constant motion. It featured a bottom cylinder that rotated once per year and housed an assembly hall; a middle triangular element that rotated once per month and housed communist government offices; and a top cone that rotated once per day and housed the press. This made it the functional and aesthetic epitome of Constructivist ideals.

Although it never existed beyond a blueprint, Tatlin’s Tower challenged preconceived notions about the form and function of architecture in the modern world.

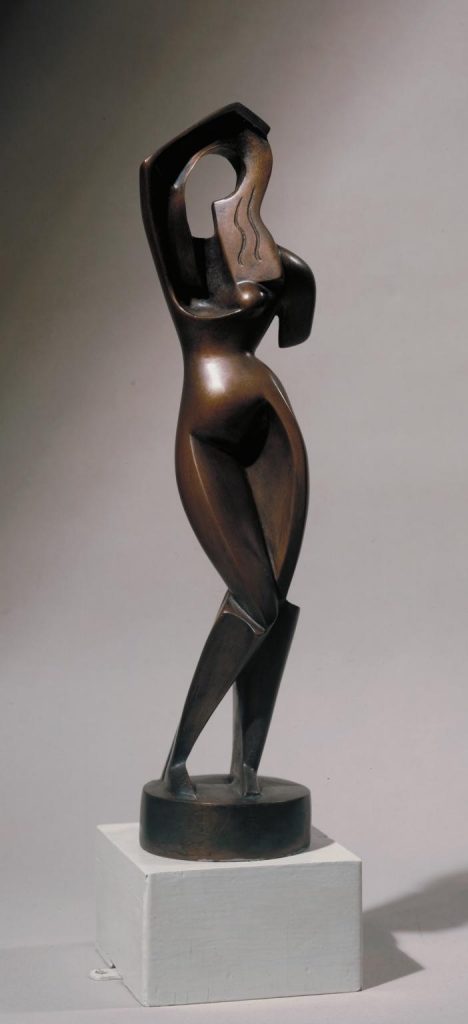

Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing her Hair, 1915, Tate Gallery, London, UK. Museum’s Website.

American sculptor, Alexander Archipenko, was born in Kyiv and attended the Kyiv Art School. After spending time in Paris, where he embraced Cubism, he became a citizen of the United States and pursued a career as a sculptor.

Besides Picasso, Archipenko was the first artist to apply the principles of Cubism to a three-dimensional medium. He reimagined the human figure as a conglomeration of simplified geometric shapes and the negative spaces between them. And, like the Cubist painters, Archipenko depicted multiple viewpoints of a single subject simultaneously in his sculptures.

Archipenko helped introduce Cubism to American audiences. His work was also exhibited as “degenerate art” under the Nazi regime—which only served to prove his important influence on Modern Art.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!