The Miniature Rooms of Narcissa Niblack Thorne

The Thorne miniature rooms are the brainchild of Narcissa Thorne, who crafted them between 1932 and 1940 on a 1:12 scale. Incredibly detailed and...

Maya M. Tola 9 January 2025

3 April 2024 min Read

Perhaps you have noticed a trend in recent years: people seem to crave a return to simpler times, to homesteading, homemaking, and minimalism. We feel an urge to recycle and to up-cycle. We have taken up arts that had lost popularity, like sewing, knitting, and embroidery. And we cook. We have schedules for cleaning our homes. We have even taken up genealogical research, on the quest to return to our roots. What is our society responding to? And how can we use what we’ve learned to lead a more fulfilling life? There is a lot to learn from the Arts and Crafts movement, not only in their principles of interior design.

Everything is cyclical. Historical eras go through times of intense cynicism, broken by periods of intense realism.

– Lauren Groff in interview for The Rumpus.

Why, if modern technology has made our lives so much more convenient and easier than ever before, do we yearn for the labors that we had once abandoned? Labors we could even consider as unnecessary today? Sometimes, it’s easier to analyze our own actions in the present by going back to the past. The not-so-distant past, as it turns out. A group of artists and craftsmen joined forces in pursuit of this same quest during the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution.

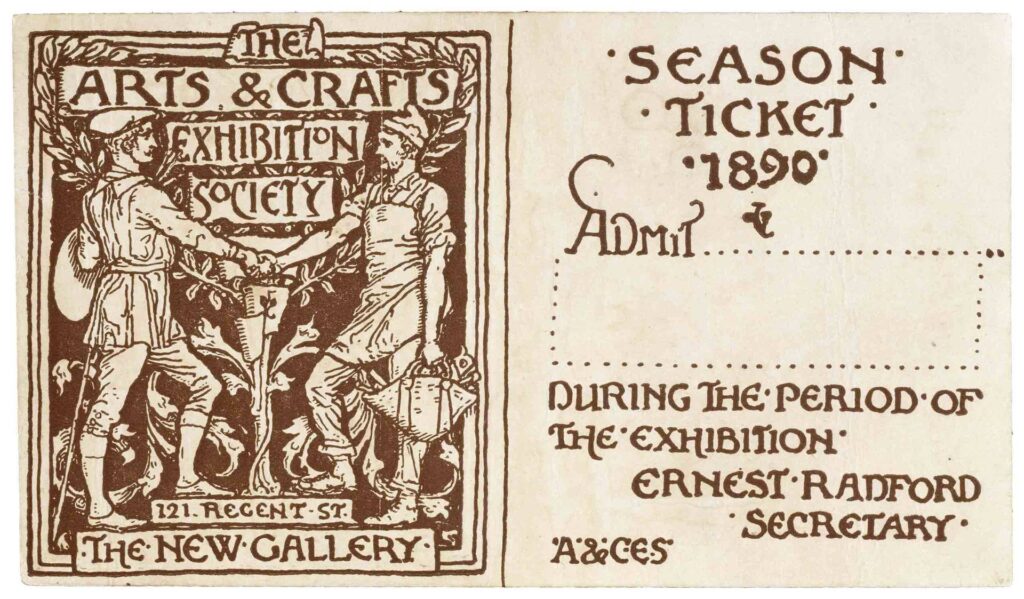

During the second half of the 19th century, industrial processes and goods were replacing objects traditionally made by craftsmen. Many of these objects were showcased during the Great Exhibition, hosted in London in 1851. William Morris was a textile designer who attended the exhibition. He noted, along with a few others, the poorly made, excessively decorated, and artificial quality of the exhibits.

Morris associated the decline in the quality of design and materials used in everyday objects with industrialization and mass production. His thinking was highly influenced by the ideas of John Ruskin. Ruskin was a writer, artist, art critic, and philanthropist – among other pursuits – who wrote about social issues. He argued that the principal role of the artist was to remain true to nature and to depict the natural world as truthfully as possible. His writings also influenced the Pre-Raphaelites, who began producing art that sought to capture the world as it was, not in its idealized version.

Ruskin disliked mass-production, as did Morris. Believing that society was headed toward an impersonal, mechanized future, Morris and the early advocates of Arts and Crafts entered a quest to return to a simpler, more fulfilling way of life.

Morris and his fellow artists believed that the key to producing human contentment, as well as beautiful items, was the connection forged between an artisan and his work. However, Arts and Crafts designers were looking for more than just the production of pretty objects. They were looking for design that integrated exteriors and interiors in a unified whole because they believed that simple, good design improved a person’s character.

This search for unified design meant that one artist could apply his aesthetic concept to many different objects and arts during a single project. Several of the leading figures of the movement had trained as architects. As these designers worked on various projects, they could transition through a wide variety of disciplines as different as woodworking and glassware. This is why Arts and Crafts is best associated with the decorative arts and architecture, and not with what were considered the finer arts of sculpture and painting.

The Arts and Crafts movement was deeply concerned with notions about the purpose of society and the treatment of individuals within that society. They were also concerned about the role of industry, architecture, urban development, and the part that man needed to play within this development.

In 1861, Morris founded the decorative arts firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. Here he hoped to model the principles he espoused. His two most-celebrated phrases, “Form follows function,” and “. . . Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” sum up the essence of Arts and Crafts interior design.

You probably have heard some variation of the motto, “Buy the highest quality you can afford.” The proponents of Arts and Crafts interior design believed the same. This would ensure that rather than having a cluttered space full of objects that you don’t necessarily love, you would have one or two items that you could rely on to function properly and to enhance your life.

This beautiful bedspread embroidered by May Morris, William Morris’ daughter, is guaranteed to put a smile on your face every time you entered your room.

Or, maybe think about coming home after a tiring day at work, and wrapping yourself in this gorgeous May Morris cloak – the epitome of luxury!

Form follows function.

The members of the Arts and Crafts movement believed that excess ornamentation was unnecessary, and an indicator of poor-quality design. Instead, they stated that objects should be designed with their function in mind, and that function would then determine their characteristics.

Not all the designers believed that everything should be entirely hand-made, however. William Arthur Smith Benson was a metal worker, and he made this teapot with a machine. However, we can see Arts and Crafts clearly through the simple lines and very clean design.

Today’s version of this mantra encourages us to only keep things that spark joy, as Marie Kondo would say. And, it makes perfect sense. When our space is filled with unnecessary items – those that drain our energy or even spark guilt – we cannot welcome new things or experiences into our lives.

Here is an example of Ruskin Pottery by William Howson Taylor. Like other Arts and Crafts interior design objects, this one is very minimalistic, relying on the bright color and the effects of the glaze as the only decoration.

This was an important tenet of the Arts and Crafts movement. Abiding by this principle meant that no object would have unnecessary ornamentation that would actually interfere with its use.

Here is a good example of this principle in action: the Morris Chair, which is one of the most iconic pieces from the Arts and Crafts movement, and the world’s first recliner!

The American designer Gustav Stickley began producing his version of the Morris Chair in the 1900s, achieving the design’s most iconic form.

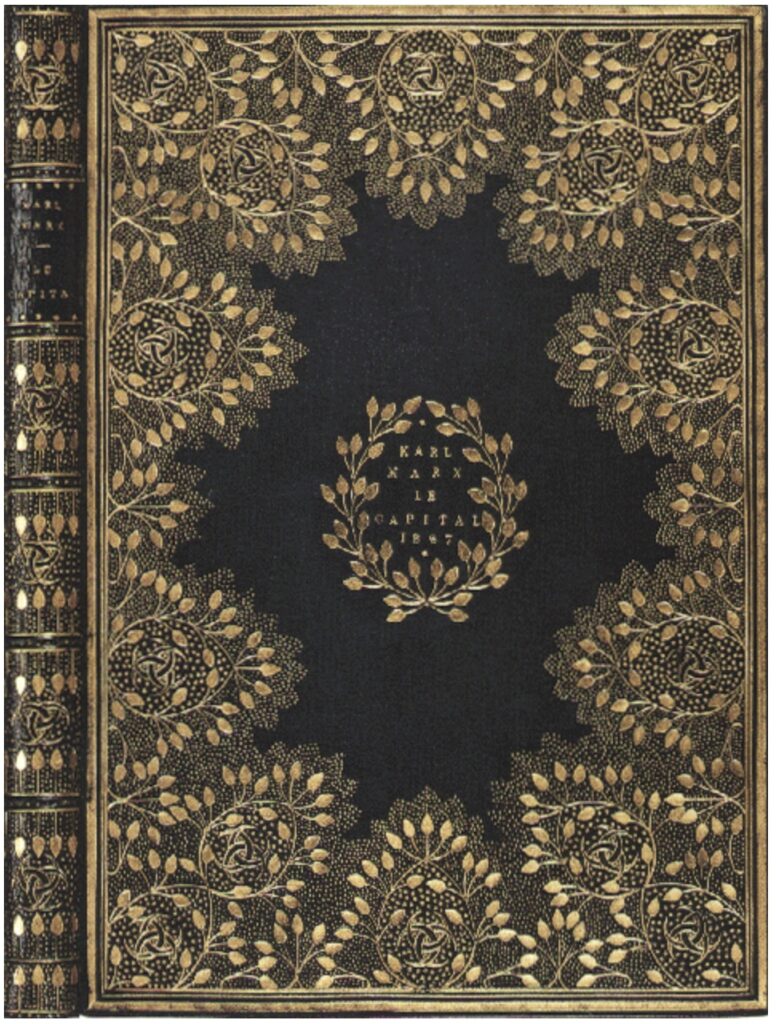

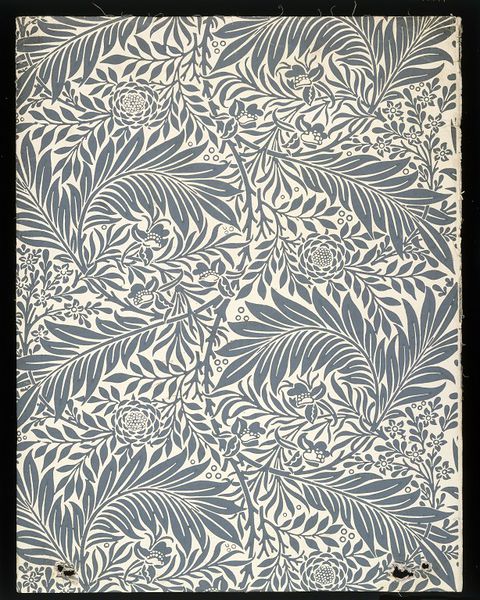

Nature in all its glory was an endless source of inspiration for the Arts and Crafts interior design artists. Stylized depictions of nature enhanced the graphic appeal of the work while keeping it beautiful and familiar.

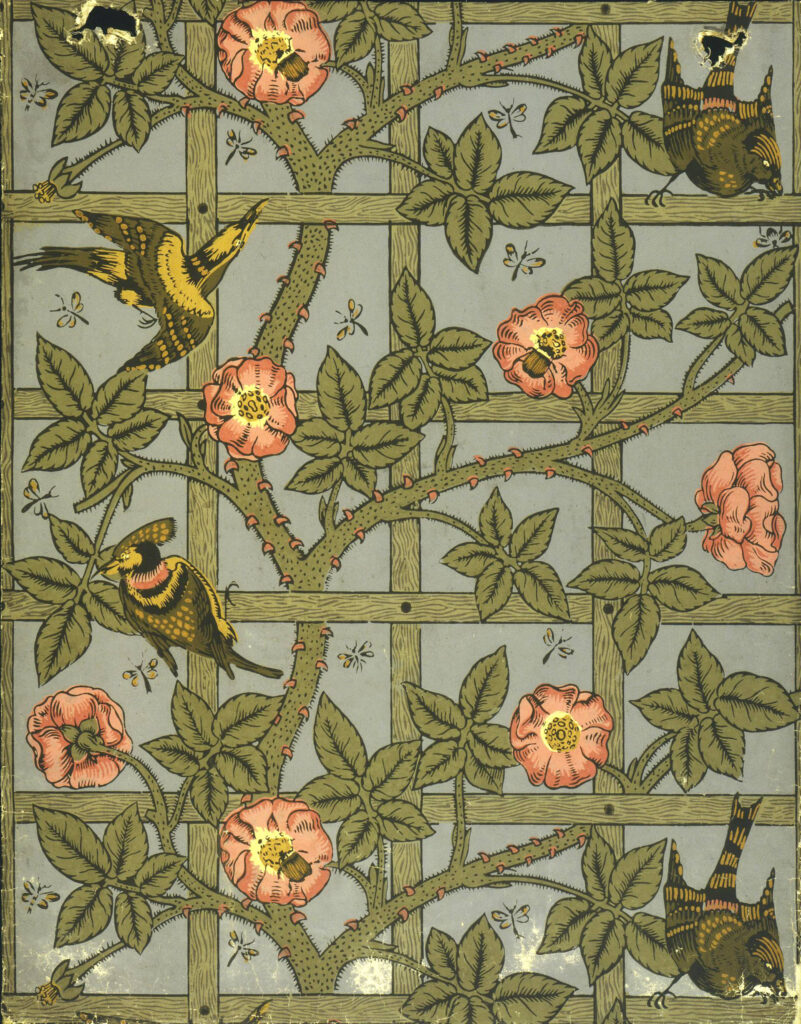

In this book cover, the repetition of a vine motif creates a pleasing and luxurious pattern.

A quick visit to the online home of William Morris & Co. shows the Arts and Crafts aesthetic ideal of stylized shapes grounded in natural forms. The Arts and Crafts movement drew inspiration from Medieval, Japanese, and Islamic art, because of their themes and the striking graphic quality of the works themselves.

Here is a detail of the famous William Morris Larkspur wallpaper pattern.

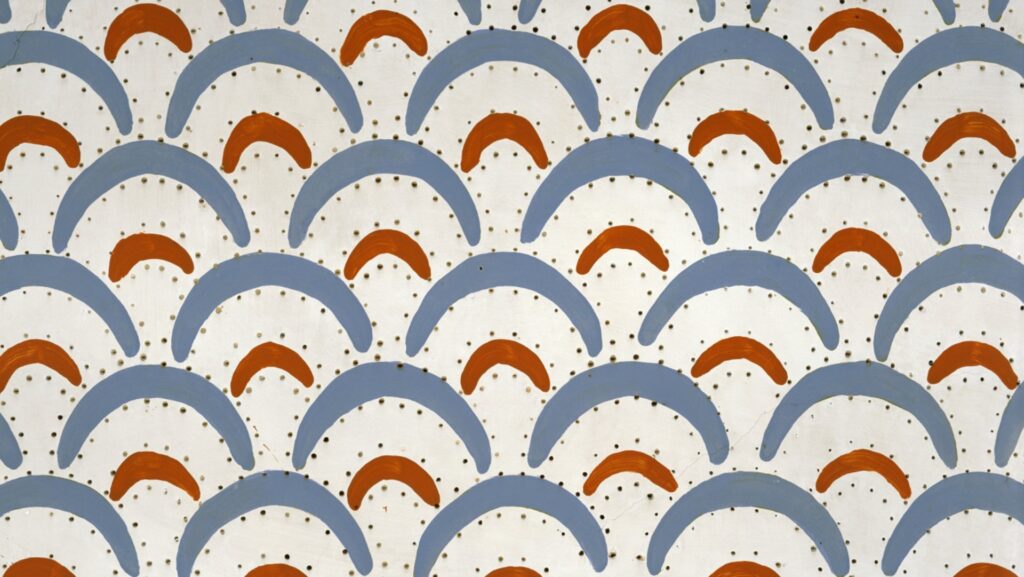

The Red House was William Morris’ private residence. In this detail of the ceiling, we observe inspiration from Japanese textiles, particularly Sashiko embroidery.

The relationship between craftsman and object was a key idea of the Arts and Crafts movement. To this end, they promoted and celebrated activities such as wood carving, block printing, and even embroidery.

Even though the first wallpaper printing machine was patented in 1839, William Morris continued to have his wallpaper printed the traditional way. He used carved woodblocks to print on long rolls of paper which were then hung to dry before the next color could be printed on top.

The Arts and Crafts aesthetic inspired by nature extended also to their color palette. The interiors of The Red House are good examples of the sort of warm, rich, earthy tones favored by the craftsmen – colors that would complement the beauty of natural wood.

Arts and Crafts practitioners sought the return to traditional craftsmanship, with the maker as a figure of importance and respect. The proponents of the movement believed that machine-made objects were not of high quality. In many cases, they weren’t. With this in mind, they placed their utmost emphasis on beautifully-made objects, created out of the highest quality materials. Unfortunately, this meant that the prices of these beautiful objects were also high.

Even though the intent of Morris and his fellow artists was to bring quality design to all people, in practice the opposite happened. His designs were so beautiful and so exclusive, that only a few people could afford them.

Does any of this sound familiar?

History is a cyclic poem written by time upon the memories of man.

– Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The words “minimalism,” “declutter,” “craftsmanship,” are now all part of our everyday conversations, not only present in Arts and Crafts interior design. Perhaps you still remember your mother or grandmother mentioning their home economics class and what they learned there. And, perhaps you’ve wondered what happened in the intervening years, that you didn’t learn those arts in school. Or perhaps you are wondering why your children are not learning them now.

As more of the home processes became mechanized during the 20th century, there was less need to learn – and rely on – the knowledge of how to do all this traditional work. And, just as William Morris, John Ruskin, Walter Crane, May Morris, Philip Webb, and all the craftsmen of the Arts and Crafts movement, some of us have felt the lack of connection. Some authors call this “flow,” which is the state of being one with our purpose and our work. When we are in a state of flow, hours can go by without our noticing, because we feel such connection and fulfillment in our work. To remedy this lack, some of us have felt the need to return to our roots and recover some of this lost knowledge and arts from the past.

And so, even though it would be unpractical – and in some cases prohibitively expensive – to completely rely on craftsmanship and homemade goods for all of our needs, we can still take a beautifully handcrafted leaf out of the Arts and Crafts book. We can use the movement’s principles as inspiration to craft beautiful, expansive, and, as William Morris dreamed, fulfilling lives for ourselves and for those around us.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!