5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

First published in 1881, Étienne Léopold Trouvelot’s portfolio of astronomical illustrations is an exceptional collection of majestic 19th-century cosmic art. It was originally produced as a luxury item and sold for 125 dollars. Now this unique celestial manual has further increased in value and remains rare among collectors and antique dealers.

Thankfully, the 15 colored plates are widely available online. As a result, the French artist’s delicate attempts to map the stars can be enjoyed by a wider set of enthusiastic admirers. However, the man’s scientific achievements in faithfully observing the universe are often undermined by his disastrous experiments with insects. Unfortunately, Trouvelot’s gifts as an artist collide with an ecological struggle that continues to cause widespread desolation throughout North America.

Trouvelot was born in the Aisne district of Northern France on 26th December 1827. As a French citizen, he was known as a trained artist and portrait painter as well as a flourishing amateur scientist. There are rumors that he escaped the regime of Napoleon III by fleeing to America in the mid-1850s, seeking political asylum. Settling in Massachusetts with his family, he expanded his interests in natural history by cultivating silkworms for fiber production. This was a practice possibly inherited from his native country where manufacture had been extensive.

Sadly, the industry in France was declining due to diseases within the species, eventually increasing to epidemic proportions. In a similar example of ecological blight, Trouvelot’s silkworm rearing resulted in imported larvae from Europe escaping into woodland near his house. The dreaded Gypsy Moth continues to wreak endless havoc in North American forests up to this day. Hence, Trouvelot’s name is forever associated with the environmental plague unleashed by this insatiable pest. Luckily for him, his growing fascination with the heavenly realm ensured a more positive legacy was bestowed in his honor.

Trouvelot’s drawings were always intended as scientific studies of physical marvels rather than artistic works. His careful observations resulted in over 7,000 images during his time in America. But these strange, alluring visuals remain artistically significant due to their overwhelming grace and extraordinary wonder. Nowadays we are familiar with striking images of space and the cosmos. No less awe-inspiring than Trouvelot’s works, photographic pictures somehow lack the elegance and charm that make his pastel studies so naively characteristic. Here we can experience the other-worldly splendor of the universe through the eyes of a century still enthralled by the mystery and wonders of outer space.

Accordingly, Trouvelot’s amazingly accurate investigations possess dual offerings for the viewer. He skillfully manages to factually depict astronomical subjects whilst artfully expressing the natural awe and exaltation within such grand phenomena. Employing centuries-old hand-drawn methods such as those practiced by Galileo, Trouvelot’s stargazing scrutiny relied just as much on the well-trained eye as the telescope. In fact, astrophotography during Trouvelot’s time was very much in its infancy. Confident in his own creative abilities, he dismissed photography as “so blurred and indistinct that no details of any great value can be secured.”

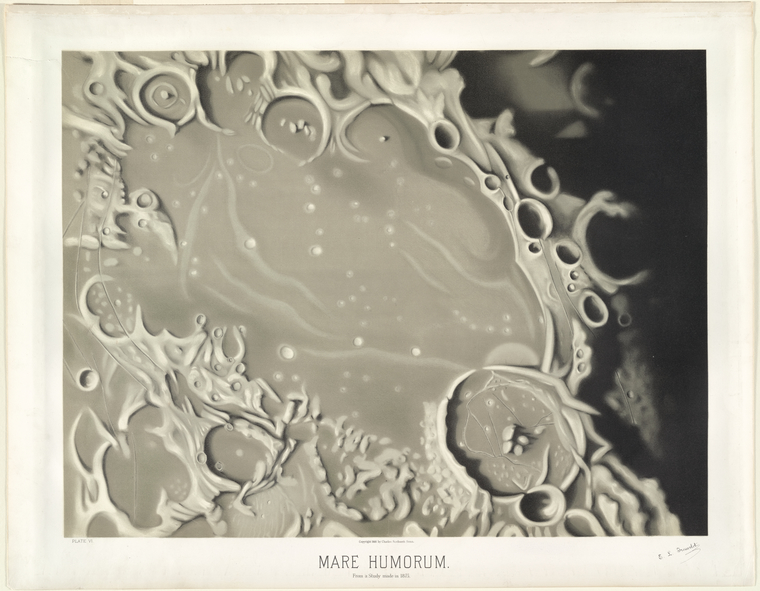

An earlier fascination with the study of insects lent Trouvelot’s imagery a degree of organic fluidity. Celestial objects achieve a sublime, ethereal presence in his drawings. Close analysis of the Moon’s surface grants its jagged surface a ghostly vitality. Rugged lunar cavities seem to pulse and flow. In the text that complements his illustrations, Trouvelot awarded the Moon a great amount of respect. Although not possessing the “dignity of a planet”, our coldly brooding satellite is a sphere very much alive in these sumptuous portraits.

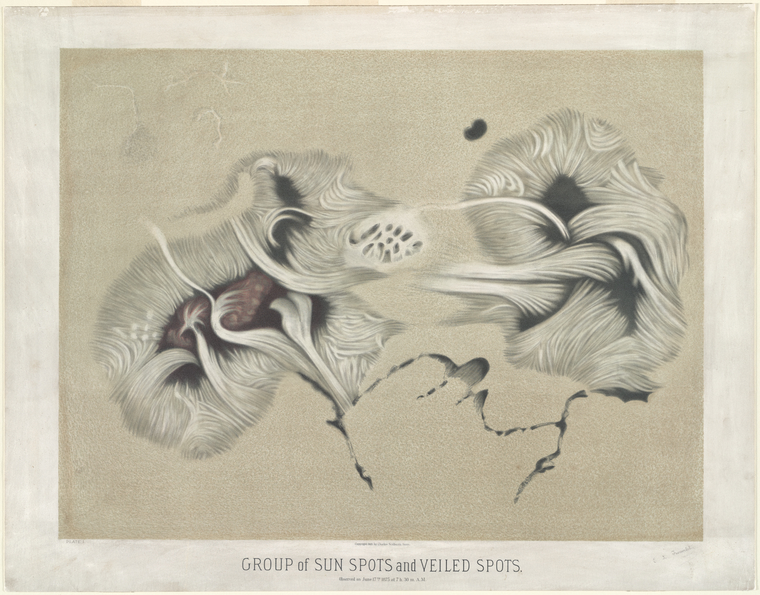

Likewise, Trouvelot’s depictions of markings on the surface of the Sun are remarkably vivid in their graphic intensity. The opening plate in his printed portfolio is a decorative display of solar energy. These sunspots appear to be staging a swirling, ritualistic dance. Their rippling forms merge and sway. It isn’t difficult to imagine them as curious entities battling for galactic supremacy. As we witness the magnificence of the universe, it is Trouvelot’s masterful vision that allows us to experience its power in a very mortal way.

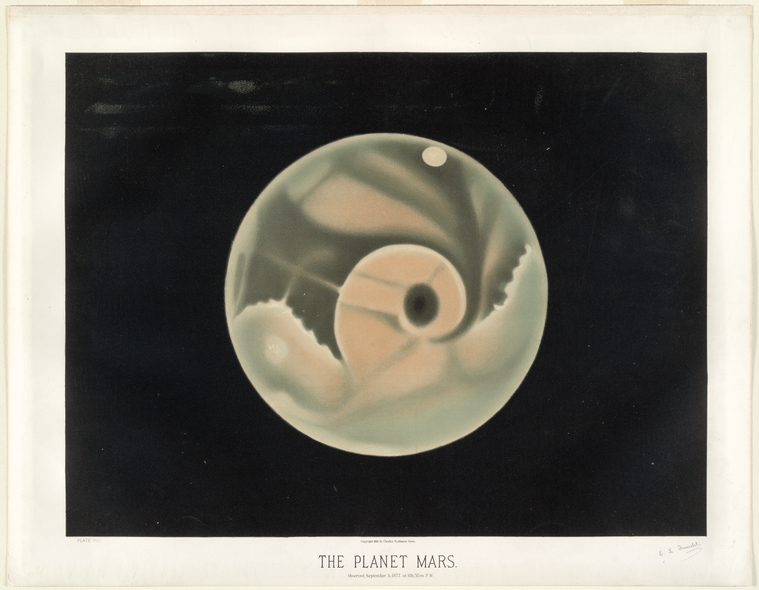

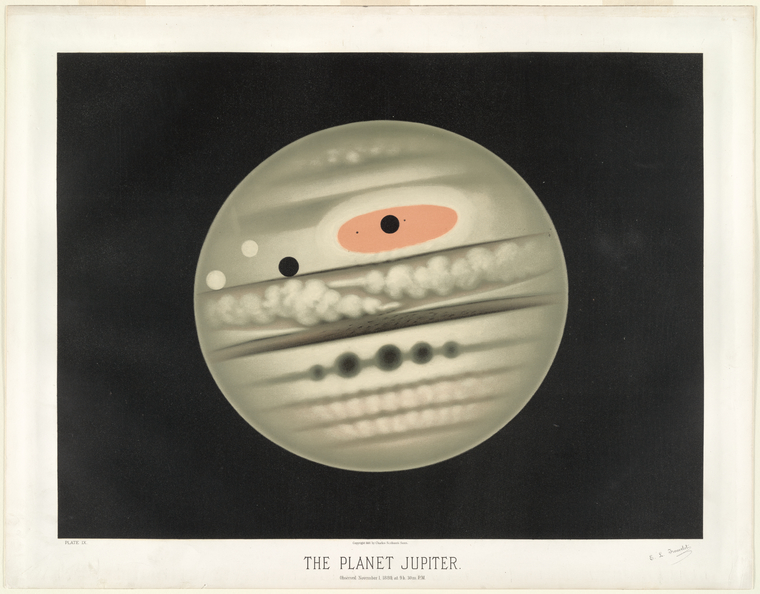

Perhaps the most startling examples of Trouvelot’s cosmic surveys are his dreamlike representations of planets in our solar system. For instance, his phantom projections of Mars and Jupiter occupy a particularly weird corner of our earthly imaginings. They resemble transparent marbles containing serpent-like shapes or odd surveying eyes. As science often gives way to human anxiety, Trouvelot’s art can be viewed as a supreme example of man’s ultimate fear of the unknown. These versions of our closest alien worlds are probably nearer to our own innate fantasies than we realize.

By 1872, Trouvelot was a member of staff at the Harvard College Observatory. He had been invited by the college’s Professor of Astronomy, Joseph Winlock, who had been impressed by the artist’s portrayals of celestial auroras. With access to powerful telescopes, Trouvelot was able to magnify the galaxy like never before. Until the improvement of photography some years later, his work was regarded as very reliable astronomical research. In an endearing tribute to Trouvelot, a scene from a 1966 episode of Star Trek includes a print of his Jupiter picture mounted on a wall.

Returning to France in 1882, Trouvelot continued his drawings of the cosmos up until his death in 1895. When his work is assessed today, we are able to recognize how both science and art can be understood in mutual terms. After all, if our Universe is interpreted with mere cold facts, we surely fumble for the spectral magic that informs our basic fascination. These pictures perfectly capture the eerie beauty of the heavens. The innocent reverence for Creation that informs Trouvelot’s work is the essential quality that makes us uniquely human.

The New York Public Library has issued their copies of Trouvelot’s plates here.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!