Masterpiece Story: Buddha Dated 338

Buddha dated 338 is a masterpiece of Buddhist art and Chinese art with deep historical significance. It exemplifies the early blending of Indian...

James W Singer 14 December 2025

24 April 2023 min Read

Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (Клином красным бей белых!) is a 1919 lithographic Soviet propaganda poster by artist Lazar Markovich Lissitzky, better known as El Lissitzky. It is considered a symbol of the Russian Civil War, showing both sides of the conflict in a propagandistic manner.

To give a little bit of context, Russian society faced numerous problems at the beginning of the 20th century. Some of them were famine, inflation, and the economic crisis after World War I. People were moving to the cities where the working class was growing. This, combined with the rise of the revolutionary consciousness led to social unrest, workers’ strikes, and military rebellion. After a series of Revolutions, the abdication of the Tsar, and the Civil War, a new government was established. Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge was created shortly after the Bolsheviks had waged their Russian Revolution of 1917, during the Russian Civil War.

Lissitzky attempt at propagandistic art was in support of the Red Army. Two sides of the conflict are represented by the red triangle (the revolutionary Red Army) and the white circle (the anti-Communist White Army). In this dynamic composition, a vast red triangle pierces into a white circle. It symbolically refers to the Red revolutionaries penetrating and prevailing over the White Army. The white background may represent a bright future ahead of the nation.

Lisskitzky’s poster exemplified the objectives of the Constructivist movement. It is futuristic, containing new tools, and new styles. At the time artists were all about moving forward.

According to El Lissitzky and his colleagues, art produced before the Revolution was outdated. Moreover, the art market based on the patronage of the bourgeoisie was corrupt. The Constructivists believed that art should serve the nation and that the people should determine the needs of art. Moreover, the main goal of Constructivist art was to bring Russia into the future.

By Constructivism we must understand a movement that does not consider art’s task to be the fashioning of sculptured busts or groups, of trinkets or paintings, of the picturesque, but the application of the entire accumulation of artistic mastery for the making [..] useful objects. Constructivist artists have stopped working for museums and toward exhibitions and for the satisfaction of “aesthetes’” desires. They have decided to fill only production orders […] Constructivists believe that an object that’s well-made and without decoration has value.

Osip Brik, “Our Agenda” (1921), in Selected Criticism, 1915-1929, Monoscope, October 134 (2010), trans. Natasha Kurchanova, pp. 82-83.

Constructivism was more than art – it was a philosophy that originated in 1913 by Vladimir Tatlin. The term was first used as a derisive term by Kazimir Malevich to describe the work of Alexander Rodchenko in 1917, and as a positive term in Naum Gabo’s Realistic Manifesto of 1920.

INKhUK (Institute of Artistic Culture) in Moscow was the place where Constructivism was officially established in 1921. The First Working Group of Constructivists (including Wassily Kandinsky, who was a chairman) defined Constructivism as:

The combination of faktura: the particular material properties of an object, and tektonika, its spatial presence.

The Program of the First Working Group of Constructivists, 1921, Moscow, Russia, in: Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism, 2nd edition, New Heaven, CN, USA: Yale University Press, 1983.

Constructivism was about an entirely new approach to making objects, one which sought to abolish the traditional artistic concern with composition, and replace it with “construction.” The movement called for a careful technical analysis of modern materials. It was hoped that this investigation would eventually yield ideas that could be used in mass production, serving the ends of modern, Communist society. But, Russian Constructivism was in decline by the mid-1920s. To a certain extent, this was because of the Bolshevik regime’s hostility to avant-garde.

Constructivism would continue to be an inspiration for artists in the West, sustaining a movement called International Constructivism. This movement flourished in Germany in the 1920s, and its legacy endured into the 1950s. Constructivism’s influence was widespread, it influenced major trends such as the Bauhaus and De Stijl. This movement had a major impact on architecture, sculpture, graphic and industrial design, theatre, film, dance, fashion, and to some extent music.

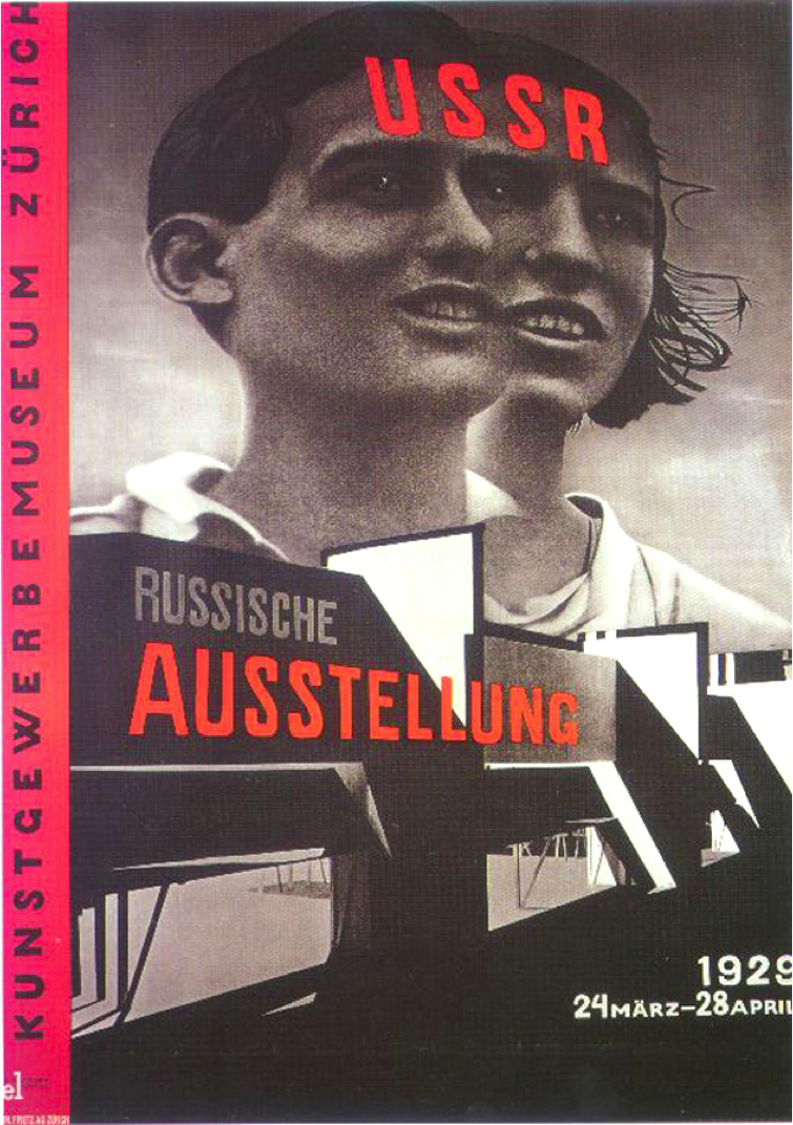

In 1921, El Lissitzky became the Russian cultural ambassador to Weimar Germany. During his stay, he was working with prominent artists of the Bauhaus and De Stijl. It can be argued that he influenced them to a certain extent.

In his last years, he influenced the change in typography, early photomontage, exhibition, and book design. He produced critically respected works and won international prizes for his exhibition design. This continued until 1941 when he produced one of his last works – a Soviet propaganda poster rallying the people to construct more tanks for the fight against Nazi Germany.

He passed away in December 1941, at his home in Schodnia, outside of Moscow. He influenced future generations of artists and key figures of the avant-garde movements of the 20th century.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!