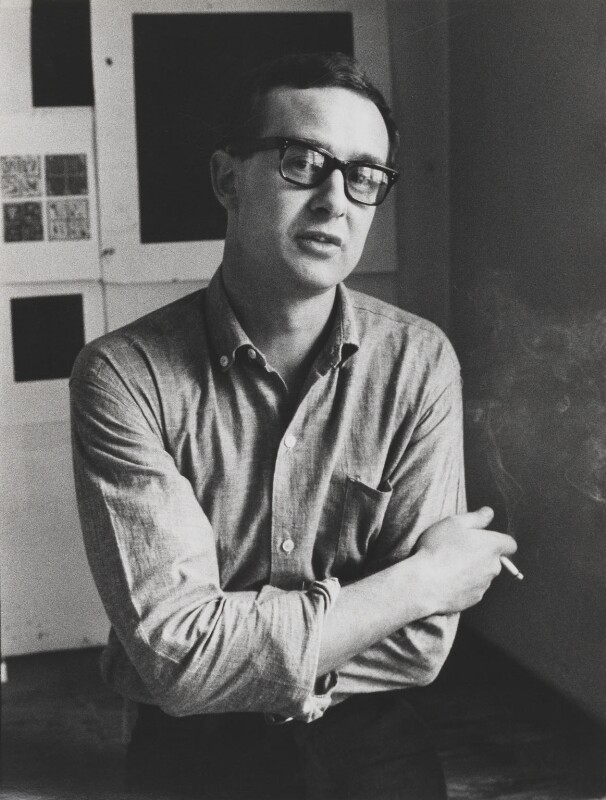

In a grim and conservative post-war Britain, Robyn Denny burst onto the art scene like a Holi festival colour bomb. He arrived at art school in London in 1951 just as British art was looking away from its European heritage, over the ocean to America, where Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art were making waves.

A euphoria of modernisation and a fascination with urban popular culture was sweeping the art world and in 1956 Denny was blown away by a Tate exhibition showing paintings by American artists including Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock. His wife, British watercolour artist Anna Teasdale, explained that this was his ‘road to Damascus’ moment. Teasdale was married to Denny between 1953 and 1975. She explained to The Telegraph newspaper in 2018:

He stayed true to that absolute belief in the abstract. It was like a light: once he had found it, he carried it around forever.

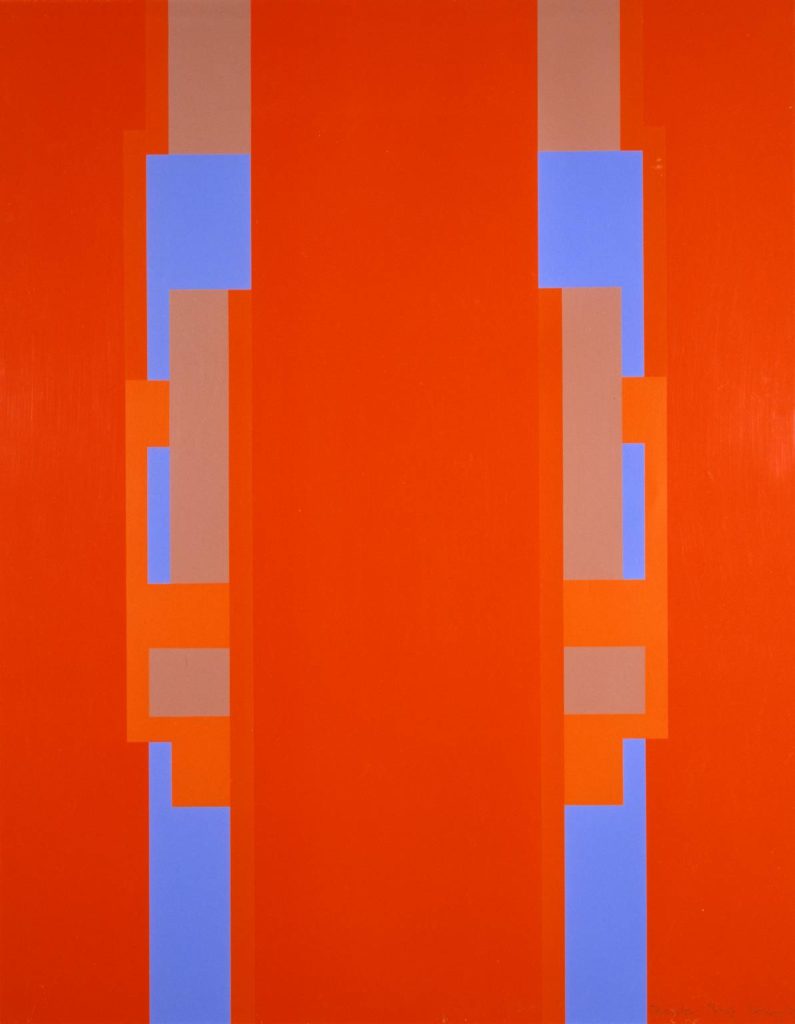

Inspired by the American greats, Denny started to produce colossal, experimental abstract paintings. Exploring light, space and perception, the size and vivid colours of these murals drew the attention of critics, some of whom were appalled. One critic famously said of a joint show between Denny and his good friend Richard Smith: “To ignore it would be unforgivable. To praise it would be impossible.”

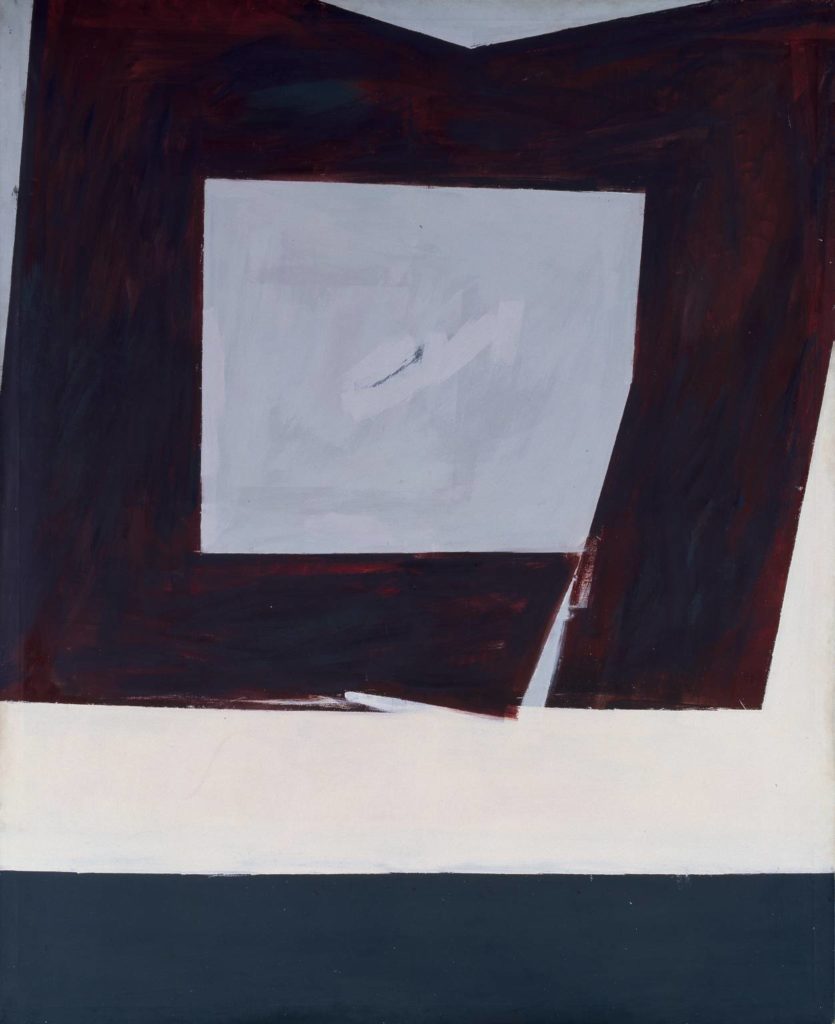

It is difficult to explain or over-estimate the impact of Denny’s paintings at this time. His work was an explosive reaction to the British tradition of landscape painting. Denny himself said that abstract painting should be diverse, complex, strange and unaccountable. His vast canvases confront us at eye level. The canvas is a flat surface, but with density and depth – we feel we could walk into it. Our eyes are in a constant process of adjustment – colours and shapes flicker. We are engaged in a full sensory experience, perhaps even overwhelmed.

By the mid 1960s, Denny was the darling of both public and critics. The Beatles chose one of his murals as a publicity shoot backdrop. He represented Britain at the Venice Biennale and he was taken on by the art dealer of the moment, Kasmin Gallery. When he was just 43 he was given a retrospective at the Tate, making him one of the youngest artists to ever receive that honour.

In 1981 Denny moved to America. Just like his contemporary, David Hockney, he was drawn to the friendly Californian urban environment. But he didn’t take to the American work ethic and the emphasis on ‘selling’ art and cultivating critics. Yet it was here that he produced magnificent canvases with multiple layers of rich acrylic pigment. Referencing the luminous light in these canvases, art historian David Mellor called Denny an abstract Turner.

But then along came the provocative YBA’s (Young British Artists like Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas) and Denny’s name inexplicably dropped out of favour with the British art scene. In the 1990s he returned home, but by then he was no longer as big a name as his contemporaries Howard Hodgkin, Bridget Riley and Peter Blake. Like Pauline Boty, he seemed to have slipped out of sight, although in fact he was running a huge studio in Southwark, producing his Moody Blues series.

His final works adopted organic forms, perhaps suggestive of flowers or rocks and show an artist still with huge inventive and creative powers.

Denny died at his home in France in 2014. In an interview

for the British Library Denny marvelled at the talent of his friend Richard

Smith. About his own work he said:

I was not a bright nor talented person.

I think we may have to disagree there. Because in truth, in a 60-year career, Denny helped to change the face of British art. He pulled it, sometimes against its will, onto the twentieth century world stage. Critic David Mellor said that he produced some of the most accomplished abstract paintings made in Britain in the twentieth century.

Denny had decided on art as a career in his early teens. A wild, free life was what he was looking for, and I suspect that is exactly what he found.

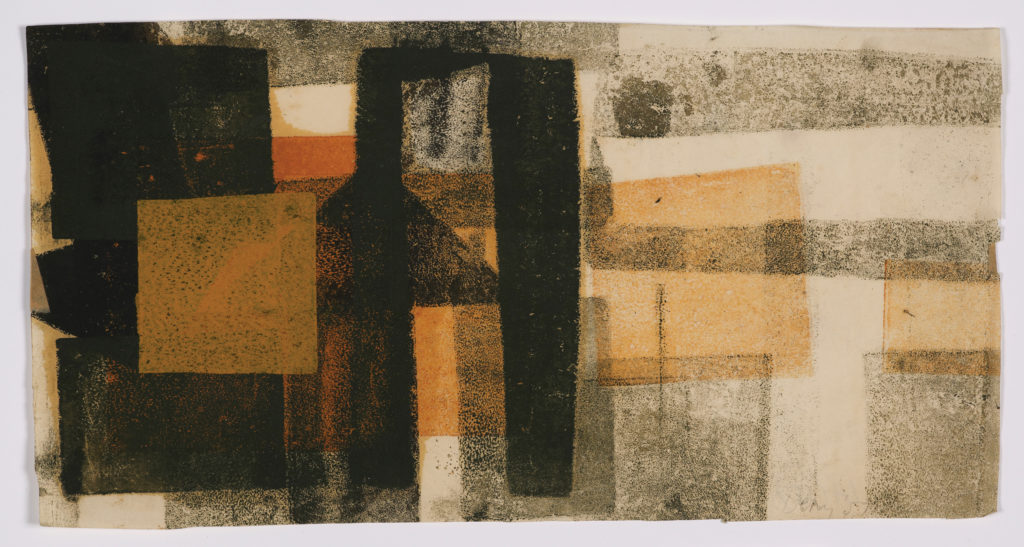

Bernard Jacobson Gallery is having a career-spanning exhibition of Denny’s works on paper in London from October 10th to November 16th 2019. Some of these works are being exhibited for the first time. To see something of his public art, drop by Embankment tube station which still carries Denny’s vitreous enamel panels painted in 1985.